Planning the Shade Prescription

When a patient comes to consult for esthetic treatment, the consultation appointment is divided into 1) a conventional evaluation with charting, periodontal, occlusal and radiographic surveys; 2) diagnostic models and photographs; 3) an esthetic evaluation involving an esthetic analysis and a focus on the patient’s esthetic requests.

The media image displayed in many advertisements has a very strong influence on contemporary dental treatment. Increasingly, today’s smile is part of a youthful dynamic appearance characterized by whiter teeth which often fall beyond the range of traditional shade guides. To that extent it is possible to identify two types of patients: “perfect-minded,” and “natural-minded.”

Category 1

Patients in the first category will typically expect maximum regularity and alignment along with maximum brightness and a “generally sparkling effect.” It will be critical to provide for these patients a straight dental midline, a regular smile line (often flatter than the curvature of the lower lip), symmetric central incisors, and lateral incisors and canines, along with symmetric gingival margins. (Fig. 1, right lateral view of an ideal smile for a “perfect-minded” patient).

Category 2

Natural-minded patients will typically expect a general sense of regularity and alignment along with definite brightness, but do not wish for their teeth to be noticed at every turn. In any pleasant smile, pleasing tooth symmetry is found close to the midline; therefore, the central incisors must be mostly symmetric with only minor irregularities (a central incisor may be more mesially inclined than the other, and the distal incisal angle of the central incisors may be bilaterally asymmetric). The main asymmetry will be provided between the lateral incisors. The canines will also provide minor asymmetry as their gingival margins and their cusp tips do not need to be leveled horizontally. The depth of the incisal embrasures should be of a natural depth in addition to providing a natural progression (Figs. 2, 3). These pictures also illustrate the need to provide these patients with subtle polychromatic effects: incisal halo, streaks and increased cervical saturation.

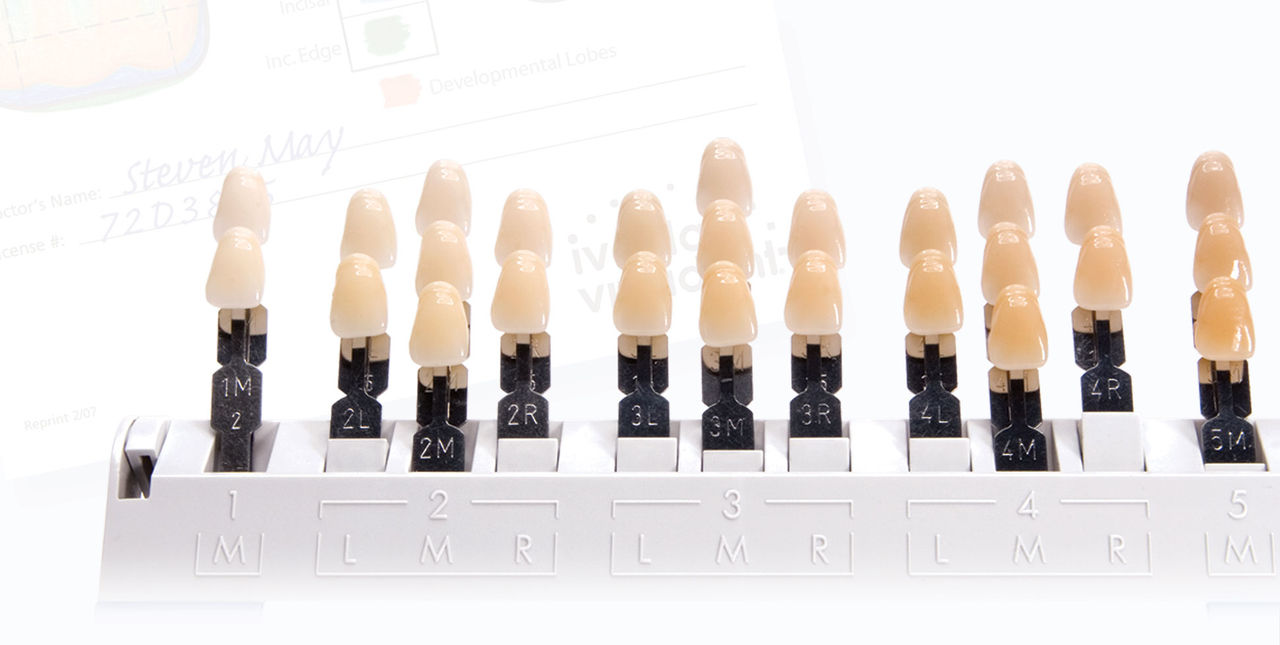

When planning the shade prescription, one must bear in mind that the most frequent shade variation from the basic shade of an anterior tooth is observed in nature at the incisal third. The next most frequent category observed is when the shade distribution is nearly uniform, resulting in a monochromatic appearance.

In the third category, the color deviation from the basic shade is observed at the cervical third mostly, and finally, in the fourth group, the shade variation involves the middle aspect of the tooth. In order to give the patient an idea of what incisal effects are possible, the incisal aspect of the shade tab is discussed with the patient after the basic shade is selected. The patients’ reaction usually is to prefer incisal effects similar to the shade tab if they are natural-driven, and to attenuate the effects to the maximum if they are perfect-driven.

There are three typical scenarios that may be transmitted to the dental ceramist:

Scenario 1 – Lightly Monochromatic Shade Design

It is very common to find patients who are so displeased by the dark appearance of their teeth that they end up requesting very monochromatic and high brightness restorations (Figs. 4, 5). The shade prescription is accordingly straightforward and uncomplicated, and the dental ceramist will assume that the incisal effects are very tenuous and hardly noticed.

Scenario 2 – Lightly Polychromatic Shade Design

There are situations where several shades and various degrees of discolorations coexist in the same mouth. Also, there are situations where different ceramic systems are present and do not perfectly match with one another.

In such situations, the rule is to assure for maximum patients’ acceptance of the restorations by keeping the central incisors at a slightly higher value than the other anterior teeth. If the value of the central incisors ends up at a slightly lower value due to some excessive translucency, for example, then it is very likely that the patient will reject the final result, even with the best-designed proportions, display and length. Therefore, in situations where the patient desires a natural appearance or when several different colors or ceramic systems are expected in the final outcome, a lightly polychromatic system should be considered.

Typically, a mild transition in shades will be produced whereas the central incisors have the highest value, followed by the lateral incisors and finally the canines. Whenever possible, this effect should be very soft. However, it allows for an easy transition from a light central incisor to a dark canine which was not bleached (Figs. 6, 7). It is very important in such transitions to keep the value of the lateral incisor closest to the central incisor even if the canine is of a much lower value.

Scenario 3 – Lightly Monochromatic Shade Design with Effects

The typical incisal effects found on unworn incisors include 1) halo effect; 2) transparent incisal border; 3) dentin streaks or mamelons; and 4) proximal translucency (Figs. 8, 9). These are the typical shading effects young unworn incisors have, imparting a very pleasing effect to the tooth shade overall. The incorporation of these effects for the natural-driven patients yields the above shade prescription. It is recommended that the clinician provides in such situations the same template each time so that nuances and variations recorded from patient to patient may be more easily interpreted.

Figs. 2, 3, 6, 7, 8 and 9 are reproduced from the textbook by Chiche G, Aoshima H. Smile design. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. Inc.;2005.

References

- McLean JW. The Science and Art of Dental Ceramics. Louisiana State University School of Dentistry, Monographs I and II (1974), III and IV (1976).

- McLean JW. The science and art of dental ceramics. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. Inc.; 1980.

- Sproull RC. Color matching in dentistry. II. Practical applications of the organization of color. J Prosthet Dent. 1973 May;29(5):556-66.

- Jinoian V. The importance of proper light source in metal ceramics. In: Preston JD. Perspectives in dental ceramics (proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Ceramics). Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. Inc.; 1988. p. 229.

- Hegenbarth EA. Creative ceramic color: a practical system. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. Inc.; 1989.

- Miller LL. Scientific approach to shade matching. In: Preston JD. Perspectives in dental ceramics (proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Ceramics). Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. Inc.; 1988. p. 193.

- Nakagawa Y, et al. Analysis of natural tooth color. Shikai Tenbo. 1975;46:527-37.

- Sekine M, et al. Translucent effects of porcelain jacket crowns. 1. Study of translucent patterns in the natural teeth. Shika Giko. 1975;3:49.

- Chiche G, Pinault A. Esthetics of anterior fixed prosthodontics. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. Inc.; 1994.

- Chiche G, Aoshima H. Smile design. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. Inc.; 2005.