One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: 20 Questions with Dr. Michael Miller

In this month’s One-on-One, I had the opportunity to sit down with one of my mentors in the dental industry — Dr. Michael Miller. Within the first few years of graduating from dental school, I found one of Dr. Miller’s REALITY books at the practice of a friend. It happened to be “The Techniques” book, before it was available in its current online form. When I opened it up, I was amazed by what I saw: step-by-step descriptions of how to accomplish practically every procedure in esthetic dentistry. The directions were concise and easy to understand, and the clinical pictures were some of the best being published at the time. Most of us did not learn these esthetic techniques in dental school, and to be able to see them deconstructed in this summarized book of procedures was like a post-graduate program in esthetics. I started subscribing the next week and have never stopped. Today, I find Dr. Miller’s honest and intelligent reviews of products and equipment to be very valuable when I am considering a new product or purchase.

Question 1: Why don’t you tell us a little about what you do there at REALITY Publishing?

Dr. Michael Miller: We are an evaluation service for products, equipment and materials with the bottom line being: we are out to protect the patient from anything that the manufacturers of these products may not have told dentists. We really look at the patient as our ultimate customer with the dental team — not just the dentist — being the intermediary. Many times both the dental team and the patient are victims to products that manufacturers may not have done their due diligence with.

Q2: That is a great goal. In fact, I like how you state you are out to protect the patients. Because dentists tend to look to some of the journals and advertisements as their main source of information, and I think we often accept it as truth. But you find instances where the product does not perform as advertised?

MM: Well, unfortunately, it’s almost impossible for manufacturers to cover every base before a product comes out today because of competitive pressures. There are bound to be some things that squeak by. And dental practice history has shown that sometimes these products, without proper testing, can cause dentists and patients a tremendous amount of grief, wasted time and wasted money.

Q3: It seems like these problem products cost the dentist and patient more than the manufacturer, which is really too bad since they don’t get to share in the pain.

MM: I always ask manufacturers how they would like to be in the place of the dentist at 8 o’clock in the evening, as the dentist makes his or her post-operative phone calls to these patients. You and I both know that when we are making those calls, we are hoping deep down in the pit of our stomach that everything has gone right. Otherwise, as soon as we ask the patient, “How are you doing?” if the patient hesitates for a moment, you know what is going to come after that. Manufacturers just don’t understand that. So what I try to get across when I talk to them is this: if the patient is having issues, the dentist is having issues. And it’s a vicious cycle. What manufacturers need to understand is it’s not that simple when something hasn’t worked out, that they can’t just replace it.

Q4: Right. And as sick as the dentist might feel about it not working, you go one level deeper; you have the patient who may be suffering and in pain because of this. Obviously there is a long chain of responsibility, so I think it’s a great thing you are doing: to help dentists steer clear of these time bombs. One of my other favorite things you do, which you didn’t mention, is the REALITY “Techniques” manual that you publish. I don’t know of any other company who has assembled a technique manual like you have for dentists to use as a reference when they go to do a procedure that they haven’t done a lot, or want to brush up on what they are about to do. Tell me: what went into making the “Techniques” manual?

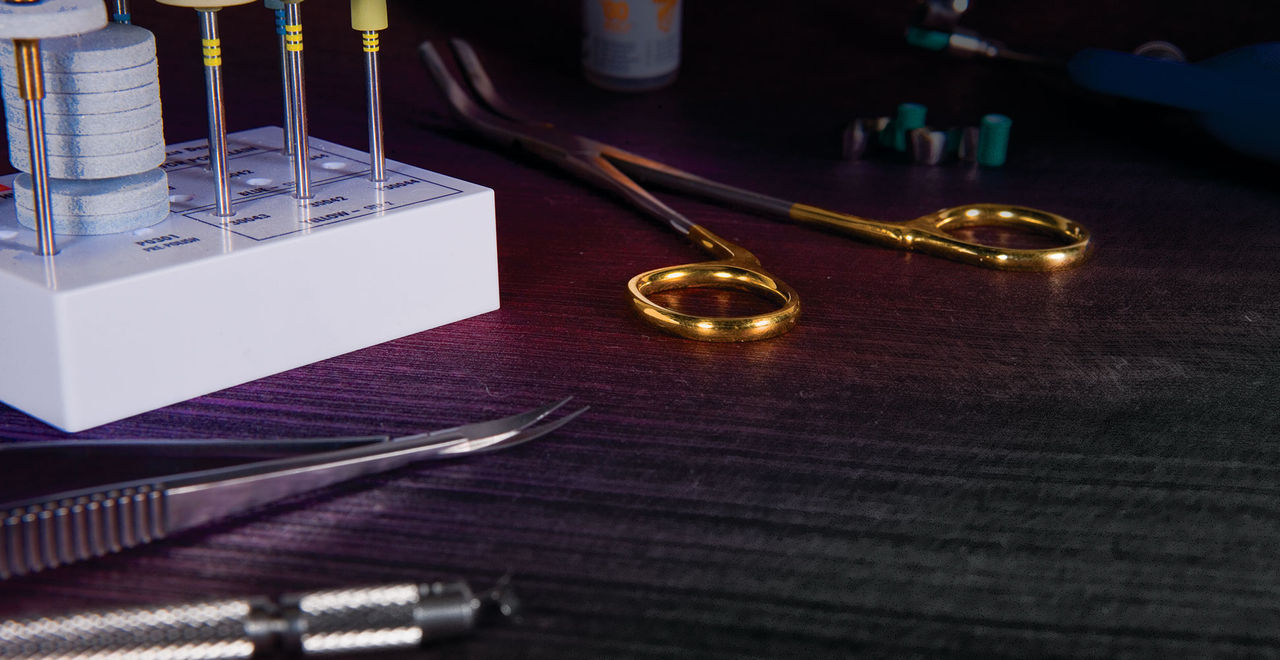

MM: Well, we used to include “Techniques” as part of our annual edition, which is now totally online. “The Techniques” procedural guide, which came out in 2003, comes from the aspect that many dentists need refresher courses on procedures that perhaps they have not done with great frequency. What we also find is that use of “Techniques” can be given to the auxiliaries — especially the assistant — and even front office staff, to help them appreciate what goes into procedures and be able to better explain these to patients. It’s not just technical information; we have over 2,400 photographs in there. I know I use it to show my patients various procedures so that they understand them better and know what they’re getting into.

Q5: That’s interesting. I hadn’t considered that because I do a lot of my own photographs, but that’s a good point. One of my other favorite things you’ve done is the instructional series on digital photography. I’ve learned how to take all the AACD standard shots from reading your material. You’re the first person that I’ve seen who showed not only how to take the photograph by what the photograph looks like, but also provide a photo of the dentist and the assistant and what they were doing to achieve the photograph. Talk to me a little bit about the role digital photography plays in esthetic dentistry in your practice.

MM: Well, I was the first accreditation chair of the AACD; I’m not sure if everyone knows that or not. And I actually wrote the accreditation guidelines.

Q6: So, just to make sure that I understand, when you mention AACD and accreditation, you’re saying you are the one responsible for direct composite veneers?

MM: I am (laughs).

Q7: As much as dentists hate that, there’s no better way to test the skills of a clinician than to be able to place direct composite veneers. But back to accreditation…

MM: Part of that, when I was writing it, was the fact that dentists and dental teams must be able to do good clinical photographs for many reasons. Not only promotional reasons and documentation reasons, but for educational reasons. I know over the years, all the photos I have taken of my own patients, I always look at them and I never fail to learn something. It makes me a better dentist. I think it’s very important for all dentists and dental team members to know how to take photographs. And thanks to digital photography, it’s never been easier.

Q8: Some dentists have told me that they shy away from digital photography because they took a course trying to sell them a $4,000 camera set-up.

MM: Indeed. Not only in “Techniques” but also in our main product database, we show that you don’t even need to own an expensive single-lens reflex digital camera (that can cost thousands of dollars once you add on the lens and flash). You can go out and buy an off-the-shelf digital camera for a couple of hundred bucks, as long as you are not trying to make these photographs into large posters for the ceilings and walls of your operatories. Anything over three megapixels with an off-the-shelf camera can take better than average digital shots of patients, even in the posterior. So, I think today it’s very easy for anybody to take digital photographs of their patients, no matter what they are doing. And it’s an essential part of anybody’s practice, or should be.

Q9: Absolutely. And from the lab’s perspective, spending as much time in a dental laboratory as I do, it amazes me that we still have doctors from New Jersey or New York who will send us an impression for PFM crowns on teeth #8 or #9 and not send digital photographs along with the case. I don’t know what kind of magic they expect technicians to be able to perform if they can’t see what the adjacent look like. To your knowledge, is digital photography being taught today in dental schools?

MM: Yeah, I know there are a lot of courses on photography today, and I think the AACD has been the real force behind that. Since I’m not currently on any faculties of dental schools, I’m not an expert on what’s in the curriculum. But I think that with conventional off-the-shelf cameras, virtually anybody — any assistant, any hygienist, front desk — should be able to take better-than-average digital clinical shots with just a little bit of practice. I am not discouraging anybody from getting a nice system from companies such as PhotoMed or Lester Dine or these types of companies who sell packages to clinicians. I’m simply suggesting that if somebody was worried about the expense involved, they can go down to Best Buy or CompUSA and buy a digital camera off-the-shelf for a couple hundred bucks and be able to take above average shots.

Q10: You see a lot of new products, some that obviously live up to their promise and probably some that don’t. If you had to name for me the most exciting products that you have seen in recent years, what might those be?

MM: Well, certainly one of them is the advent of electronic caries detectors, starting with DIAGNOdent® (KaVo; Charlotte, N.C.). About 20 years ago there was an electrical conductance device put out by a small company out of the Northeast that had a little smile and frown on its LCD screen. This was 20 years ago — way ahead of their time — and it was one of the first of these types of instruments that we evaluated when we started up REALITY in the mid ’80s. Then, nothing else came out for another 15 years, until the DIAGNOdent. Now there is another instrument out called the D-Carie™ mini by a Canadian company by the name of Neks Technologies (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). In a way, it takes electronic caries diagnosis to another level because it can also diagnose interproximal caries. So, I think this is one area where patients have always been suspicious when they go into a dentist’s office and the dentist says, “85 cavities.” Even now, while these electronic caries detectors are not 100% accurate, they certainly add to our ability not only to help from a diagnosis standpoint but also to help patients understand the numbers game. If you go into a physician’s office, he gives you a cholesterol score or your triglycerides [level]. Everyone wants a score today, and these electronic caries detectors definitely give you a score. From a laboratory’s standpoint, I know you guys have looked into CAD/CAM. That’s an extremely exciting area. We did a full evaluation of the CEREC® 3D (Sirona Dental Systems; Charlotte, N.C.) last year. I think our conclusion was for certain dentists who are computer proficient and have a large enough practice, that at least the CEREC 3D — and I know it’s been superseded by another generation — was definitely an exciting addition to a practice. I think that part of dentistry has been a tremendous advance. Even some of the lab systems, such as 3M ESPE’s Lava™ (St. Paul, Minn.), have made a major impact on dental restorations in terms of metal-free dentistry. The third most exciting area would be ergonomics. Dentists traditionally bend over, resulting in lots of musculoskeletal problems and repetitive use injuries. The advent of better loupes, operating microscopes, headlights — you name it — has definitely made practicing much easier and more ergonomic for a lot of dentists. I think these are the areas that are exciting.

Q11: One of the things I like about you is that you always surprise me. I’m really surprised that ergonomics was one of your answers, and it’s great to hear. I just can’t believe that I asked you about the most exciting things in dentistry, and composites and bonding agents did not come up. It just goes to show that you always keep a very open mind, and you’re not completely focused on just esthetic dentistry. I think when REALITY was started, the perception was that it was all about esthetic dentistry, how to do it and what products to use. That last answer you gave me shows that your eyes are open much wider than just the field of esthetic dentistry.

MM: I wrote an article just recently about the nano trend. There are nano trends in all of society today; everything is smaller. We see it in dentistry with nano hybrids and nano adhesives, et cetera. Really, the reason I didn’t mention composites is because there have been no revolutionary advances in composites in the last 20 years. There have been little, incremental advances, but certainly there is nothing that just grabs you. The same is true with adhesives. I have a favorite slide in my lecture programs about self-etching adhesives. The slide says: Just because it doesn’t hurt doesn’t mean that it is a better adhesive. That’s what clinicians need to know. Certainly, self-etching adhesives have their place in modern practice, but they are not the “be all, end all” that a lot of people think they are.

Q12: So, you are not willing to trade a material that gives you no post-operative sensitivity with sloppy technique for 20 megapascals (MPa) of bond strength to dentin?

MM: First of all, the megapascal race is an illusion because no one has ever shown that the higher the megapascal rating of an adhesive, the better it is. There are too many other factors involved.

Q13: What that reminds me of is when you look through dental journals, and you see all that stuff about impression materials and contact angles. They show measuring the contact angle between water and impression material. To me, it seems like 95% of the impression materials that we have today will work really nicely if you treat the tissue well and do proper retraction. And this whole battle for contact angles — is there anything to this?

MM: I think that is one of the most ludicrous things I’ve seen as well. It always amazes me that these manufacturers are putting a water droplet on an impression material and they think that has something to do with taking an impression. I’m definitely in total agreement with you. In fact, in “Techniques” we go into a lot of detail on taking an impression. I always tell everyone exactly what you just said there: taking care of the tissue is the number one rule in taking an impression. I always teach to go ahead and pack cord before you even go subgingival. It’s much easier to prevent it from bleeding than to stop it from bleeding.

Q14: Exactly. And as soon as I break contact, the double-zero cord goes into place, the final margination gets done and then I drop another cord on top of that. And from what my experience has been, if I leave a very small cord in while I take the impression I don’t see any bleeding. It seems like anytime there is something in contact with the base of the sulcus there will in fact be bleeding when it is removed. And along those lines, a lot of the diode laser companies are now suggesting that a diode laser may be a good replacement for a retraction cord. I had a case this morning where I prepped a couple of posterior teeth and used a diode laser to do a little troughing and take impressions. But when it comes to anterior teeth, I’m a little uneasy doing that. My experience has been if I use a diode laser and try to remove or trough a little around an anterior tooth, that even though I’m just trying to remove and gain enough space for the impression material, I’m going to lose some vertical height of the tissue and potentially expose a margin. And then if I drop my margin back down again, I would have to retrough it with the diode laser. What’s your feeling on using the diode laser opposed to a retraction cord for taking impressions?

MM: Well, I’m probably going to get in trouble for this next statement, but I think using a diode laser for doing what essentially a $300–400 electro-surgery can do is major overkill. I understand there are other uses for diode lasers but I have never been a fan of that. I’ve always thought that if you can control the bleeding or control the tissue right from the get-go, like you said, put in a double-zero cord or just a zero cord — whatever the case may be. If you get the tissue out of the way of your preparation initially, you will rarely ever have a need for either some type of electronic coagulation or even chemical coagulation. I’m not a real big fan of those, but I know other people are; folks on our editorial team like Dave Hornbrook swear by them, but I’m not in that camp.

Q15: We have a lot of technicians and managers here at the laboratory that really don’t like the H&H Impression Technique. They seem to find that doctors who rely on it have higher remakes and often need up to seven layers of die spacer to get the crown to seat predictably. What experience do you have with a technique like that and do you have any feelings on it?

MM: I tried it very early on, when Dr. [Jeff] Hoos first came out with that technique. But I also have to say that I’m not a triple tray or closed bite impression tray lover; I almost never use them. I will use them very occasionally for single posterior crowns where there is distal stop. So if I’m doing a first molar, I’ll need a second molar still in place. I certainly didn’t do 50 units using it. It just didn’t fit my practice style, so I can’t really comment on it from an experience level.

Q16: It seems like quality dentistry just takes some time.

MM: I think there’s plenty of evidence that if you just stick to the basics — there’s not many shortcuts that have come out recently that allow the type of excellence that even the old timers did. When I mentioned to you about not making the tissue bleed in the first place, I actually learned that from one of the true old masters, Charlie Pincus. I remember I was fresh out of dental school and went to a lecture in 1975; Charlie Pincus was on that program and he was still taking copper band impressions. I don’t take copper band impressions, but he explained the rationale: as soon as it bleeds you have a scar and scar tissue is never as good as virgin tissue. So, I believe that wholeheartedly. That’s why even going with something like Hoos — which is designed to overcome, perhaps, some of those other deficiencies and not having to use cords and so on — just doesn’t fit my practice style.

Q17: Yeah, and other products you know. Expasyl™ (Kerr; Orange, Calif.) has been out for a long time and I use it during ovate pontic surgery. I certainly have other uses for it but it’s not necessarily a retraction cord replacement, not at all. Also, there’s Magic FoamCord® (Coltène/Whaledent; Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio); and as much as I would love never to have to pack cord again, I just can’t get the same impressions with those that I get from packing cord. To me, it’s all about getting an impression of the entire preparation — and then a millimeter beyond it. That way, they know definitively where my margin is, they can see some of the root, and get some emergence profile information at the same time. I would love to be lazy but I can’t do it from a quality standpoint.

Let’s jump over to something from the laboratory. You touched briefly on Lava, and my experience with zirconia goes back about four years to when we first started doing Cercon® (DENTSPLY Ceramco; York, Pa.). Now that we’ve seen the transition to Lava, I would like to hear your thoughts. Have you had the chance to do a lot of these zirconia-based restorations, and how do you feel about them?

MM: Well, I certainly haven’t done thousands. I think in the proper place of zirconia-based restorations, Lava has been the most successful. One thing I try to preach when it comes to designing a case is don’t pick the material first. Listen to the patient, see what the patient needs, and then pick a material based on the patient’s needs. I think even with pressed ceramics many patients’ teeth were unnecessarily overly prepared, just because the dentist was told — either by manufacturers or various other educational facilities — that preparations needed to look a certain way, everybody needed to have a certain look. I think that was absolutely the opposite of what we should have been doing all along. I think the same thing goes for the zirconia-based restorations. If you are doing them in a situation where you would do a ceramic-to-metal restoration, they work really great. Indeed we have been preaching the use of totally light-cured cements, even with zirconia-based restorations, so that dentists have more control over the cementation process. That is one big advantage of using a metal-free material compared to a metal-based type of restoration.

Q18: You can’t flip through a journal today without seeing an advertisement for no-prep veneers. We do it, and a lot of other laboratories do it, too. I was against them but changed my mind when I first started placing them. Now, there’s another laboratory actually coming out and advertising against no-prep veneers; they’re even gathering clinicians to talk about how rarely they can be used. It’s turned out to be a popular product here at the lab, so I’d like to get your input on no-prep veneers.

MM: Again, if a patient walks in and they have systematically removed their own enamel over the last 30 years of brushing with Brillo pads, then no-prep veneers are probably the restoration of choice. I’ve been very successful with no-prep veneers. It’s hard to tell somebody, “Yes, do it this way,” or “Yes, do it that way,” because each case is different. I’m big on teaching the basics of treatment planning, analyzing cases and then going from there. I don’t think there is anything wrong with no-prep veneers. As a matter of fact, I bet if the vast majority of dentists needed veneers and their teeth were slightly worn, maybe abraded, that they would opt to have no-prep — or at least very minimal-prepped veneers — rather than these grossly over-prepped teeth that you see every day in many journal articles. I’m not in favor of dogma. I’m in favor of understanding the concepts that go into restoring a patient’s mouth and thinking your way through it. It’s not a popular way of doing it, but I still feel it’s the correct way.

Q19: I was going to ask a follow-up on how you feel about minimal-prep veneers versus full prep veneers, but I think I already know what you are going to say based on that last answer. I look at a lot of preps and impressions for veneers that come into Glidewell. It appears that dentists are not only dogmatic in picking what material they are going to use before the case, but in the preparation as well. I feel a lot of cases that are fully prepped into dentin — veneers with all the enamel removed — appear to be done without the final result in mind; for example, if the patient has loss of facial enamel volume and worn away a millimeter of incisal length. Rather than deciding they want these teeth to be 10 millimeters long — we only have to prep a half-millimeter to get there — it seems like the whole millimeter and a half is taken off regardless of what the patient has lost through time. I’m guessing that you tend to look at those cases individually and, probably as a philosophy, try to stay more towards minimal-prep than full prep. Is that fair to say?

MM: Absolutely. I wrote an article many years ago saying that dentists own the schmutz but patients own the enamel. What I mean by that is there is no reason today for us to unnecessarily reduce teeth, irrespective of whether we are doing veneers, posterior teeth, even breaking contact. I’ve always told dentists that, from the lab perspective, you need to run a fine diamond strip in between the teeth so the dies can be separated without chipping margins and so on. That’s all the dentist should be doing, unless there is a compelling reason to open the contacts. So, I really think it’s a trend in and beyond dentistry, medical colleagues are discovering this, too, that microscopic techniques and plastic surgery techniques are much less invasive than they have ever been in the past. Patients are demanding it and I think dentists need to be able to think on their feet, not just pick up the handpiece and start grinding teeth down.

Q20: I like that answer. Anything on the horizon that you think dentists would be interested in? Is there a no-shrink composite out there in the future? Is there anything that we should keep our eyes open for?

MM: The no-shrink composite is another one of those things. We’ve done umpteen studies on low-shrink, high-shrink composites and its effects — the white line effect, microleakage, nanoleakage, all these sorts of things. The fact is shrinkage is only one component of a restorative material. If you could have a low shrinkage, optimally no shrinkage, material that had great handling properties, polished great, and had depth of color and low porosity — that’s not even close, I’ll tell you that much. My prediction would be 10 years. All the ones that I’ve seen, there are so many downsides to these low-shrinking materials. I think it’s overblown. The dentist can place a material into or onto a tooth properly and not believe the manufacturers that say you can put in 20 millimeters, all in one increment, and cure it in five seconds. Then the shrinkage factor on that material is almost a non-factor. I think it is way overblown and dentists shouldn’t concern themselves with that.

For more information about REALITY Publishing, visit realityesthetics.com or email Dr. Miller at mmiller@realityesthetics.com.