The Dangers of Denial

Article by Larry Hamburg, DDS

I am a dentist with oral cancer. Even worse, I’m a dentist who ignored his oral cancer. In spite of playing tennis every Tuesday with a physician friend, having many patients who are doctors and staff members who could have checked a bulge in my neck, I ignored it.

I don’t know why I didn’t act sooner. After all, I’m a doctor, and I have always told my patients to take their health seriously. But I guess I’m human first. You see, I had missed just one day of work in 24 years of dentistry and, like my dentist-father before me, I never thought there could be anything wrong with me. Somewhere inside I must have thought I could be immune from the very disease I try to help patients prevent.

But reality started to hit me in December 2006. One morning, dressing for work, I went to button my shirt before putting on my tie. The collar was tight. I assumed I was getting fatter, or older, or possibly both. But upon further examination I noticed a swollen gland to the right of my Adam’s apple. I was fighting an infection, I thought. I ignored it — for six months.

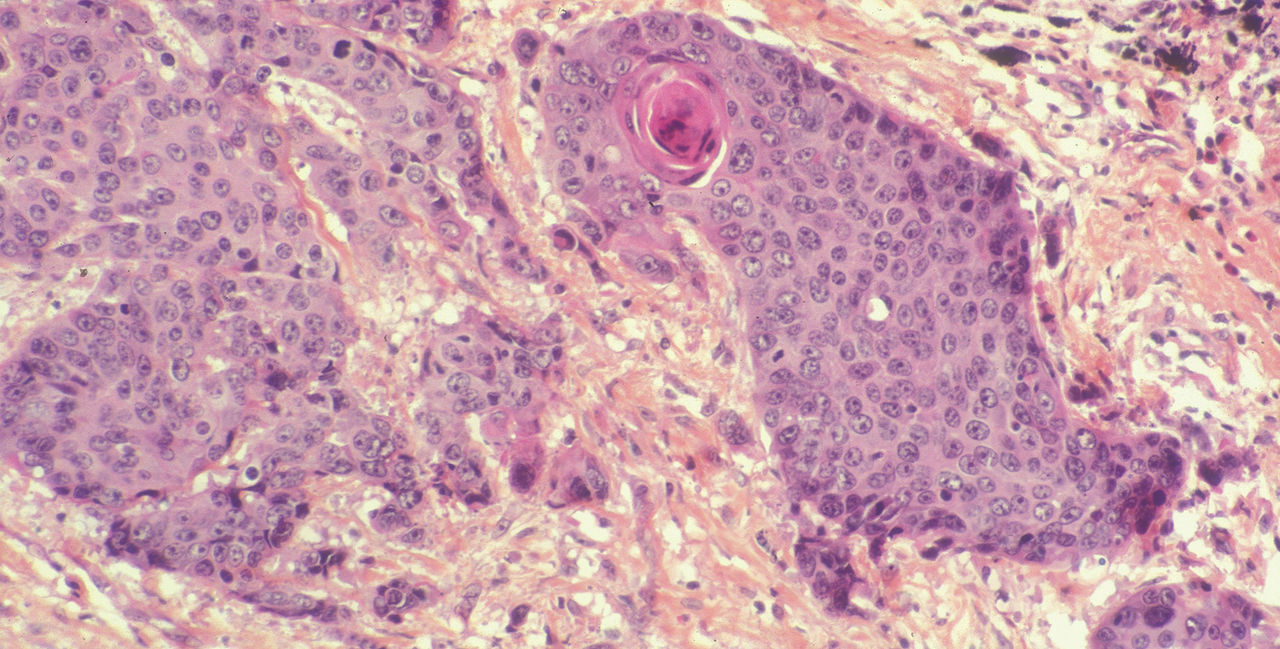

One day I asked my hygienist to check my neck. She suggested I have a doctor look at it right away. I didn’t. Then, a few weeks later, I took my nine-year-old son in for a routine checkup and asked his pediatrician (who is also my friend) to check the lump. She gave me “the look” that I won’t soon forget. Three days later I was diagnosed with a superball-size mass at the base of the tongue, with a secondary tumor in my lymph node the size of a baseball and the culprit of the bulge. The radiologist said he didn’t think it was squamous cell carcinoma, one of the most dangerous cancers. I agreed, thinking back to my days in dental school 25 years ago, when I first learned about it. The next day the cancer was biopsied, and it was squamous cell carcinoma, stage IV, the worst. I fell to the floor hysterically crying, swearing I was ready to die if that was God’s plan. But how could this be happening to me? I wasn’t ready to leave my two boys, Jamie and Ryan, my beautiful wife Anne Marie, my friends and family. I was devastated.

Three days later I was diagnosed with a superball-size mass at the base of the tongue, with a secondary tumor in my lymph node the size of a baseball and the culprit of the bulge.

The next few weeks were a daze. Every day was another doctor, another test. At one point we went to a doctor’s office and everyone seemed to know me. I had no idea why. My wife informed me this was the third time at this office in the last two weeks. I didn’t remember being there before.

Then one day Jamie, my 11-year-old son, and I went for a walk. I asked him if he had any questions about my illness. He said, “Well, it’s not like you have cancer or anything, right, Dad”? I said, “Yes, Jamie, it is cancer.” He hugged me for a few seconds and then went into this lengthy explanation of why cancer isn’t something to be so afraid of anymore. That there have been so many advances in treatment, and many people live very long and healthy lives after their diagnosis. Before that conversation all I could think of was the 22% five-year survival rate I had read about on the internet. I will never forget how brave he was, how inspiring, and how right.

Today I’m still trying to figure out why I ignored that lump, what made me think I was so different. Mostly, though, I focus on the gift of my cancer. I’m inspired to change the dental world. Studies suggest that only 20% to 50% of dentists do oral exams. Why would a dentist worry more about finding a cavity than cancer? So I’ve dedicated myself to reaching out to my colleagues, and my patients, imploring them to give and get oral cancer screenings. These days with special equipment we can actually find precancerous lesions. And the sooner we find something, the better the outcome.

Like Lou Gehrig, I consider myself to be the luckiest man on the face of the earth. Or, at least, the luckiest person coming out of the 10th floor at Beth Israel’s Head and Neck Cancer ward. Unlike others there I kept my tongue and vocal cords. Outside of a lengthy scar on my neck (I tell people it’s from protecting my wife in a bar fight), the loss of my taste buds and salivary gland function (which doctors hope, but can’t guarantee, will return in a few months), and some numbness in my fingers and toes from chemo and radiation treatments, I’m fine. I’ve suffered through six chemo treatments and 33 radiation sessions. I survived a week in the hospital, including surgery and radiation implant therapy, where I was in isolation for 48 hours, except for occasional 15-minute visits from my parents, my sister and my wife, who also have been so brave and inspiring.

Like Lou Gehrig, I consider myself to be the luckiest man on the face of the earth. Or, at least, the luckiest person coming out of the 10th floor at Beth Israel’s Head and Neck Cancer ward.

Recently I returned from a trip to the Yankee Dental Conference in Boston, Massachusetts, where I had the honor of lecturing to more than 350 dentists about cosmetic dentistry, and included the necessity of oral cancer screening, and the use of a new device called a VELscope to help detect oral cancer sooner. My mentor and friend, Dr. Gerard Kugel, told our mutual students, “If you don’t do oral cancer screening you don’t deserve to be a dentist.” I couldn’t agree more.

I believe I know why God didn’t let me lose my ability to speak. I’m on a mission. I’m here to spread the word about oral cancer (which has increased in incidence by 11% in the last year). Next month my office will have an open house oral cancer screening day. Perhaps I will be able to get other dentists to do the same.

Today, at 51, I’m a better dentist. I’m a better husband, a better dad, probably a better man. And I appreciate every minute of this fragile life so much more.

Larry Hamburg, DDS, lives in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

From Newsweek Web Exclusive, Feb 6. ©2008 Newsweek, Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of the Material without express written permission is prohibited.