One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: Interview of Dr. Paul Homoly

In this month’s “One-on-One” interview, I had the opportunity to speak with Dr. Paul Homoly again. One of the things that I like about Paul is his contrarian viewpoint, and this interview is no exception. Paul talks about the culture of dentistry and how it affects what we do and say as practitioners. Our “accidental education,” the beliefs we acquire unintentionally while learning clinical dentistry, begins in dental school and continues through organized dentistry, publications and CE courses. Read this interview with an open mind and see how you feel about Paul’s unique thoughts regarding patient education.

Dr. Paul Homoly: The culture of dentistry is like any culture in any other community. A culture is based on a widely held belief of the community. Culture means “shared belief, shared behavior, shared activity.” Our actions, our thinking and our behavior are largely driven by belief systems. It’s similar to traveling to Italy where you’ll find a certain culture in place. Coming back to the United States after traveling there, suddenly you notice certain things about this country you didn’t see before. That’s true with professional cultures, too.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: I had that same experience and here’s an example. When I came back to the United States from Europe, I noticed everybody watched television in the evening, while there, everybody socialized, often going to the pub. I miss that socializing.

PH: In the 16 years I’ve worked with dentists, I’ve spent time in other professional cultures — principally financial services and legal organizations. In working closely with these lawyers and financial planners — both personally and their associations — it’s become obvious that these industries have a culture of their own. In this sense, the culture refers to how people have developed shared beliefs, shared behavior and often a shared language.

When I returned to dentistry, I noticed that this profession has a cultural center, which is called clinical quality. All roads lead to clinical quality. Compare that to the cultural center of financial services — its education, periodicals, universities, academic drive — which is geared toward a return on investment. In law, the industry’s cultural center points toward influence. Whether an attorney is influencing a jury or a judge or a community or the constitution, the focus is on influence.

In my experience, the standard of dental care in the United States is the best — which is a good thing. What’s the downside? Dentists might sacrifice other aspects of their lives and practices to have that high degree of clinical quality.

Now, what if suitability replaced clinical quality as the profession of dentistry’s cultural center? What if we consciously pursued suitability with the same vigor, intensity and resources we put into pursuing clinical quality? Then we’d no longer have permission, in the cultural sense, to make huge blunders in the name of clinical quality — blunders most people can’t perceive.

For example, dentists might make business decisions that work against them — building or remodeling an office that’s too big, for example, and draining their finances as a result. They might drive up their overhead by purchasing too much equipment, building a facility that’s too large, or hiring too many people. Consequentially, they paint themselves into a corner. Economic pressure mounts. It gets harder to produce clinical quality. Why? Because of too much stress related to the business side. They move from a 1,500-square-foot facility to a 5,500-square-foot monster with an in-house laboratory and the whole bit. They end up with a $6,500 a month mortgage. They’re financially stressed, but their production doesn’t go up significantly. Then they become depressed; their relationship skills go down; they lose staff members. Ultimately, their pursuit of clinical quality ends up destroying their lives.

MD: It’s amazing to think that a dentist might purchase something like a piece of equipment in the name of clinical quality, but it’s so expensive, the cost of that equipment hampers the dentist’s ability to deliver quality dentistry. As you say, prosperity is not our cultural center — not what we seek. Consequently, a lot of dentists are out there pursuing clinical quality, many times at the expense of their prosperity. Their decisions to pursue quality are often counter to their creating wealth in their lives.

PH: Yes, you’re not aware of a particular culture you’re in until you leave it. And most dentists have never left. They know what they’ve learned in dental school, from their dental colleagues, at dental society and association meetings, and from books and periodicals — all culturally influenced. As a result, rank-and-file dentists never question the cultural beliefs because they don’t fully recognize the ones in place!

MD: And there might even be a subset of the dental culture in the dental school with the full-time instructors versus part-time instructors who have private practices on the outside, so dental students may get exposed to a certain brand of this outside culture.

When you’re a student in dental school, you’re a sponge ready to absorb all this information — more so than in any future point of your career. You get exposed to a certain subset of this culture which may or may not serve you well in private practice. But while you’re focused on the gutta-percha on the X-ray, you’re getting all this cultural education at the same time.

PH: Yes, these dentists think they’re doing the right thing, but it becomes an invisible poison. That is, doing things in the name of quality actually poisons them in the long term.

You see, when dentists feel economically stressed, patients can sense a neediness or desperation, depending on the language used. If a dentist gets uptight about money, his or her behavior and language could cause a dissonance in the dental practice. The staff picks up on the negative vibes. What results? An environment of fear. And that’s the poison. Isn’t it ironic that it happens in the context of striving for quality?

MD: With the staff, it might go beyond sensing pressure to feeling it, even panicking. The dentist might say: “We’re having a bad month. We need to get these three patients to accept treatment plans and start them today.”

PH: Absolutely. It happens all the time. Some practice management specialists actually teach dentists how to have this conversation with their team, saying: “OK, here’s the deal. We need to make production, and we need to sell these cases.” This heave-ho approach can become toxic, which ultimately disturbs the dental practice’s ability to produce quality.

You see, quality as defined in our dental culture includes the physical specifications and technical characteristics of clinical outcomes. Think of it as the tightness of the margin, a 20-micron margin, the crispness of the occlusion, the esthetics of the contours, the translucency of the porcelain. But how many of these clinical specifications can the patient really appreciate?

MD: Not many. It cracks me up the way dentists throw around how many microns a margin may or may not be open. The only way to measure that is to extract a tooth, section it and put it under an SEM. Most patients are unaware of this measure. For dentists, the concept is more nebulous than they care to admit to themselves.

PH: And patients are probably the last ones aware of quality above and beyond what they can readily recognize — a shade match, an appropriate bite, a ballpark reasonableness of clinical accuracy. So clinical quality doesn’t come from the patient’s experience, but from the experience of the dentist and the dental team.

When I was in practice, I’d typically have a surgical patient who would arrive early, take the meds, follow instructions about not eating, and so on. When the anesthetist hit the vein with the IV, the patient would go into deep conscious sedation without a problem. I’d prep the mouth and face, make rapid incisions, and clean dissections. The operating field was bloodless. I’d create implant receptor sites, drop implants into place, close the flap effortlessly — like I had magic hands. Everything worked well. That’s clinical quality — like a candle whose flame burns bright and the whole team feels it.

But quality is the experience of the practitioner creating the dentistry; it’s not the outcome for the patient. Only the dental team shares that experience; the patient isn’t a participant in that event.

What the patient experiences is some degree of “suitability,” which is different than quality. Suitability for the patient includes questions about being able to afford this treatment. It also includes a clean facility, friendly dental team, conveniently located office and workable appointment times. To sum up, suitability refers to being an easy place to do business with.

Now, what if suitability replaced clinical quality as the profession of dentistry’s cultural center? What if we consciously pursued suitability with the same vigor, intensity and resources we put into pursuing clinical quality? Then we’d no longer have permission, in the cultural sense, to make huge blunders in the name of clinical quality — blunders most people can’t perceive.

MD: That certainly would require creative destruction!

PH: Yes. We would have to take an intricate look at who we are and ask, “Am I a provider of quality clinical services or am I provider of suitable clinical services?” I’m not arguing against the inner experience of quality here. That inner experience kept me on fire for 20 years and drives most dentists. That’s in a dentist’s nature and culture both.

However, sometimes our culture evolves more slowly than the world does. For example, I’m Catholic and when I was growing up, it was a mortal sin to eat meat on Friday. If you ate meat on Friday, and you knew it was Friday, and if you died right after that, you would go straight to hell. Well, I went to a public high school and I remember going to the cafeteria line and getting the meat ravioli. I would forget what day it is as I sat down to eat. I’m ready to eat this meat ravioli when one of my Catholic buddies across the table would say, “Hey, Homoly, it’s Friday.” So, I’d have to choose: do I starve or do I go to hell?

The whole concept of not eating meat on Friday was set aside several years ago by one of the popes. Today, it’s perfectly okay to eat meat on Fridays for Catholics except during Lent and on holy days of obligation. But you know what? When I go to a restaurant, look at the menu, and get ready to order, what’s the first thing I think about?

MD: What day is it?

Because of people’s cash flow and financial worries, they’re not ready to select a dental practice for the long run. A practice driven on clinical quality alone will tend to drive those people away. Why? Because in an environment focused on clinical quality, they can get educated right out of the practice.

PH: What day is it! This cultural belief hasn’t gone away. It’s still there. The culture of that belief — don’t eat meat on Friday — doesn’t go away even though the world has changed. But as dentists, we’re still experiencing a cultural belief that needs to include factors of suitability. Adopting a culture of suitability, we create an environment that participants find acceptable so they’ll remain with the practice a long time.

That’s right at the heart of what is going on now in the economic downturn. Because of people’s cash flow and financial worries, they’re not ready to select a dental practice for the long run. A practice driven on clinical quality alone will tend to drive those people away. Why? Because in an environment focused on clinical quality, they can get educated right out of the practice.

MD: That’s a new concept — educating patients right out of the practice. How does that hold true, especially in tough economic times?

PH: Here’s a good example. A patient needs two 3-unit bridges and a garden-variety crown. Let’s say this bridge case is $8,000 to $9,000. This patient comes in complaining how his IRA has just gone down 35%. After a complete examination, the dentist lays out a treatment plan based on clinical quality. The patient hears the high price tag and responds: “I’m not ready. I need to go home and think about it.” Six months later this patient comes back for a cleaning and the hygienist asks, “Are you ready for your bridgework?” The patient says no because of the cost. At the next cleaning six months later, the hygienist again asks. Again, he says no. Six months later at his next cleaning, he remembers feeling irritated and says, “Don’t talk to me about the bridge!” Then he breaks his next appointment for cleaning. When he finally has the money, he gets the bridgework done by a different dentist who didn’t nag him.

That’s how we can educate patients out of our practice. The dental team’s “patient education” feels like sales pressure to the patient.

MD: And a slow economy not only breeds patient unreadiness, but also causes classically trained dentists to ramp up their focus on “patient education.”

PH: Yes, people in crisis hang on to their original culture. That’s why when times get tough, dentists tend to educate more. But as a dentist, I can’t change the economic climate or the stock market; the only thing I can change is me and my practice. The solution? Increase the suitability of my practice to my patients.

Yes, people in crisis hang on to their original culture. That’s why when times get tough, dentists tend to educate more. But as a dentist, I can’t change the economic climate or the stock market; the only thing I can change is me and my practice. The solution? Increase the suitability of my practice to my patients.

MD: So what types of things can we dentists look at differently?

PH: Let’s address the usefulness of patient education, which is at the center of our culture, one of its commandments. Is educating people really the right thing as we’ve been taught?

Now, of everything our role models and teachers have said, some have worked, some didn’t — just like some things my parents said haven’t worked out. But just because some of their advice didn’t work out doesn’t invalidate their entire body of work. Even though I don’t advocate a lot of the cultural beliefs traditional dental gurus espouse, that does not mean I don’t respect or love or honor them, as I do my parents. I think dentists have a hard time with that. They’ll listen to a dental guru and believe they have to do everything he or she is doing, but that’s not the case.

In fact, part of what never worked for me as a practicing dentist was blind adherence to the patient education model geared at changing patients’ behaviors. In the process, we aim to increase the value of dentistry in their eyes by educating them about the conditions in their mouths. We even attempt to change their beliefs about what’s important in their lives, making statements like, “You shouldn’t go on this vacation; you should get your teeth fixed instead.”

MD: That goes beyond education.

PH: Yes. Some would call it supervised neglect. That’s when patients aren’t ready for care, but they need the care so we accommodate them in our practice without doing that care. We are, in fact, guilty of supervising the neglect of their teeth. In a way, we are tacitly approving their self-neglect. The believers and the proponents of the supervised neglect axiom believe you should remove patients from your practice who are not taking your treatment recommendations seriously.

MD: Then they drive that point home by saying it will be one of the biggest areas of litigations within the next 10 to 15 years, and dentists will be sued.

PH: Yes. They throw a fear factor out there and dentists become afraid to do anything. Why?

Well, let’s look at the patient education model. It’s based on dentists changing their patients, believing that if we educate them well, we can change their belief and value systems. Once we educate them, they will see the light and fully appreciate the care, skill and judgment of their dentists. Then, when presented with treatment recommendations, they’ll willfully embrace them and integrate them into their life. Their treatment recommendations will supersede other priorities they have in their life. I remember a guru saying that when patients fully understand their conditions in their mouths, they’ll happily go through treatment.

MD: That simply fails to take into account many different variables.

PH: But from dentistry’s cultural point of view, this makes perfect sense. Traditionally, the pursuit of quality is what we’re about. We influence our patients to think the way we think and assert ourselves to the point of saying to them, “This is what you should do with your life.”

Now, it’s extremely difficult to change behavior. If you think it’s easy to change a person’s behavior, just marry him or her. But why doesn’t education work? Because the premise is false. Education does not lead to change.

Even the beginning student of instructional design knows that the key to change is not education; it’s the readiness of a person to change. Take someone who doesn’t want to lose weight and put him on a weight-reduction plan, or someone who doesn’t want to stop smoking and put him on a smoking cessation program, or a person who doesn’t want to stay married and put him or her into marriage counseling — what happens? It’s their readiness, not their understanding, that drives their behavior.

MD: In fact, I would assume if somebody came in ready to make a change in their dental health, they wouldn’t even need to understand the entire process. Education wouldn’t be the most important factor.

PH: Absolutely. People make decisions when they’re in love with the desired outcome, even when they’re not fully aware of all the processes involved.

So after a decade of trying to change patients’ behavior, and in the absence of their compliance, dental team members get burned out; they get cynical. They present a traditional treatment plan and explain all the steps, yet people are walking out of their offices. One day, they snap and say: “Damn these patients! They don’t appreciate us; they don’t know what quality is.” The dental team members never see the real problem: their inherently destructive culture.

MD: They all put their hearts into the practice, but can’t easily see they’re failing.

PH: The lucky practitioner is the one who blames the patients and the staff, but the practitioner who really gets into trouble is the one who blames himself or herself. When confidence crashes, it affects the doctor-patient relationship and the dentist team’s ability to produce clinical quality.

Cynicism is a sustained stress — a sustained negative relationship with the environment. Cynics aren’t happy about a thing. The psychopathology related to perfectionism and cynicism directly results from the cultural belief that “we’re smart enough to change people.” But nobody has that power. Psychologists know their patients will only change when they are ready, so they become expert listeners striving to understand people. In fact, psychologists have insurance codes for understanding patients. But in the dentistry culture, we don’t have codes for understanding patients. We have codes for educating patients. In this culture, there is no conversational exchange between dentists and patients. It’s all directed one way.

Let me ask you this: If you show me a picture of something I want and you’re not educating me, you’re actually reinforcing my desired outcome. But if you show that same picture to people who don’t want that pictured outcome, what’s the result?

MD: You annoy them.

PH: That’s what dentists can do. We explain why our patients should want this treatment and shouldn’t get annoyed. When they walk away, we say, “Well, they have low dental IQs.” It becomes the fault of the patient!

But what if the public school education operated like that? What if a teacher had failing students and the principal came up to her and said, “You know, your students consistently fail 60% to 80% of the time, right?” And the teacher replied, “Well, these students are all screwed up; they don’t value education.” What would that principal say to that?

MD: “You’re fired”?

PH: That’s right. But nobody has the authority to fire the dentist. So when patients come in who need advanced-care dentistry, a high percentage of them aren’t ready to invest thousands of dollars. And when the dentist tries to educate them into readiness, they walk.

Typically, fewer than 5% of a dentist’s $10,000-plus case patients are ready to receive care the first time they hear their treatment recommendation. What about the 5% who agree to treatment? Their decisions are based on a lot of things, but not on the education. They say yes when their treatment plan fits into their lives, they’re ready for it, and they want the outcome. Many have already walked in wanting a specific outcome.

MD: You can see how high suicide rates among dentists tie into that. In other cultures like the financial services industry and the legal industry, you don’t see the same type of belief that you do in dentistry.

PH: The blind pursuit of any cultural icon results in vast disaster. So if you’re a financial services provider blindly pursuing return of investment, you could ruin lives in the process.

MD: We’re seeing that right now — the blind pursuit of reward without risk, right?

PH: That’s it, Mike. In dentistry, the blind pursuit of clinical quality leads us to outcomes we’d never thought we’d run up against. The “blind” quality needs to be tempered with this concept I call “suitability,” which forces dentists to ask, “Is this dental treatment the next best step in this patient’s life right now?” It’s not heresy to ask this question. In fact, you have to ask if you want to develop a practice that sustains downturns in the economy, and if you want to develop a practice that provides exquisite, consistent, high-quality care.

There’s no downside to what I’m saying. When you engage the patient in a conversation about how suitable this dentistry is at this time, you’re setting into place a process that will protect your relationship with the patient in the absence of readiness. If you say: “You know, Ed, now that I’ve looked in your mouth, I know we can help you. But I’m not sure how this plan best fits into your life right now. You’ve mentioned you’re traveling to Europe a couple times a month and you’ve got boys in college. How do we fit this treatment into your life? Do we do it now, do it later, or do it a little bit at a time?” That conversation seeks to find suitability, doesn’t it?

What if the center of dentistry wasn’t the blind pursuit of clinical quality but providing suitable dentistry — dentistry that fits into the patient’s life and exceeds standard of care? Here’s the good news. Most dentists already meet 50% of these criteria for suitability. Most dentists have already gotten the “exceeds standard of care” part.

However, suitability isn’t in our culture like it is in residential real estate sales. I’ve worked with real estate agents and companies as a consultant and speaker. I’ve bought several houses, and you know how the process goes. You and your honey walk into a realty office, plop down into the chair, and start talking. “We’d like to buy a house.” The real estate agent asks, “What’s your price range?” and “How much money do you have for a down payment?” and “What neighborhood would you like to live in?” These questions land firmly on the side of suitability. That agent is “qualifying the client.”

Now, if a dentist refers to “qualifying the patient,” it sounds like a mortal sin in the dentistry culture. It sounds like, “Oh, you’re just diagnosing the patient’s wallet.” Yet somebody has to make the case suitable. There’s nothing wrong with diagnosing a person’s wallet if it’s done in the spirit of suitability. You buy a car and look at the sticker price first. But there’s no sticker price on dentistry.

MD: In dentistry, communicating fees is usually saved for the end of the initial appointment. Dentists frontload the conversation with expectations of clinical quality before they drop the cost bomb at the end.

PH: Although it sounds ridiculous, that’s how it’s always been taught and what feels right. But if suitability were at the core of dentistry’s culture, it would completely change the conversation. The typical dental exam would change, both for a comprehensive care patient and a modest-care patient. There would be less emphasis on what and how we’d do the treatment, and more emphasis on when. The conversation turns to them with questions like: “Tell me about what will work for you. Let me tell you what your outcome can be. When you and I agree on the outcome you want, I can design a path to help you get there.”

Here’s another example. In financial services, a fee-based planner gets paid on giving advice only, no commission from an insurance plan or will or pension. It’s purely an advocacy role. The word “advocate” means to guide. So you and your spouse visit your fee-based financial planner and say: “We’re thinking about building a $700,000 home. The whole project might cost us a million dollars.” The financial planner says: “Let’s see, you have $250,000 in savings right now. You have some bonds over here, some cash over there.” After crunching the numbers, he says: “Based on market conditions and how much money you have, it’d be wise to hold off buying for a year. Let’s stash some cash instead so you can increase the down payment and get a better interest rate.” The point is, the fee-based financial planner helps find a way to build your house but doesn’t help you build it. That’s the role of the advocate.

So the way to manifest suitability is to increase the dentist’s role as the patient’s advocate. Dentists help their patients find a way to get their teeth fixed.

MD: When does this conversation occur in the relationship?

PH: In a new patient interview. This conversation replaces details about how often you floss or brush every day. Yes, we’d still do exams, but the emphasis, the energy and the intention of the conversation is being the patient’s advocate, not the patient’s educator.

In my conversations with patients, I’m carefully listening for condition-related disabilities. Why are they unhappy with the partial? Why are they unhappy with their front teeth? I need to get a sense of how the condition is interrupting their lives. This sets the stage in the patient’s mind that it’s a dental office quite unlike any other because we discuss the suitability of care based on the outcome he or she wants. In fact, we discuss the suitability issues before the technical issues.

Here’s an example. Michelle comes in and she’s got unsightly front teeth; she’s not happy about the large composite fillings, incisal edge irregularities, and so on. I ask: “Michelle, how does this bother you? Tell me about a time when it really bothered you the most.” (This is a great question to discover disability.) She replies: “I own an art studio and people are coming in. They’re looking at my teeth and it’s embarrassing. I’ve really lost confidence with customers.” That’s her disability.

Then I engage in a casual conversation and say, “Michelle, tell me about your art gallery.” Doing that levels the playing field between the dentist and the patient. The dentist is no longer in the authority position. There’s no more expert-novice relationship in that moment; we are both equals. So Michelle talks about her gallery and the conversation leads to talk about home and family. As she’s disclosing details about her life, I’m disclosing bits of mine. During that conversation, I’m listening for details that will relate to the appropriateness of her full-mouth care. I find out how stressed she is, how much money she’s spending, what social and family obligations she has. I learn that Michelle has a black-tie event coming up, that she’s active in the local Chamber of Commerce, and she travels on buying trips, going to Italy and Spain four times a year. She’s a busy woman.

Then I do the exam, sit the chair up, and think about the suitability of a treatment plan for her more than I think about clinical quality. Ninety-nine out of 100 dentists sit the chair up and talk to their patients about the clinical aspects of their cases. The conversation is about what’s wrong clinically and how they can fix the problems in the mouth.

MD: Instead, what would make them feel more comfortable is knowing the dentist takes into consideration the suitability of a dental treatment for the person’s current circumstances.

PH: Exactly right. In this case, I talk about the outcome Michelle is seeking, then I link that to her circumstances. When I sit that chair up, I’d say: “Michelle, we see a lot of folks just like you — folks who want to look better at work and have more confidence in social situations. We want you to know you’ve come to the right place. I can do all those things for you.”

That’s an outcome statement to assure her that she’s in the right place. Then I say, “Michelle, I know that I can help you, but I don’t know when is the right time for you to do all of this.” I’m also saying that dentistry of this nature can be complex, expensive and time consuming, so it can interrupt her work flow. Then I ask this question: “You’re traveling four times a year to Europe and you’re working long hours at the gallery. How can we fit this into your life, Michelle? Do we do your care now, do it later, or do it a little bit at a time? Give me a sense of how we can pace this for you.”

MD: What a liberating question for the dentist, but more importantly, for the patient! To be able to put the ball in their court, let them dictate the pace of treatment rather than trying to force it along. I can see how patients would react positively to this approach. They may actually do it faster than if you dictated the pace because they now have a say in the treatment plan. It reminds me of how patients are able to control pain medication at hospitals by pushing a button themselves. Even a recent study on mammograms showed how women would push down on the plate 10% harder when allowed to do it themselves. How powerful that is — giving patients control over their treatments.

PH: “Liberating” is the perfect way to describe this conversation. I call this conversation an “advocacy” dialogue, and the role of the advocate is to guide. This guiding conversation does a couple of things.

One, it states the outcome to the patient: “Michelle, I know I can help you. I’ve seen patients like you all the time who are busy with careers, but at the same time, you have some dental challenges that need to be addressed. We do this work all the time and we love doing it. I know I can help you.”

Two, I’m telling the patient what she’s already thinking, which is, “Wow, what am I getting into?” She’s got these problems, she’s talked to friends who’ve had dental work, she’s heard good and bad reports about this condition. How bad is it for her?

Next, I say to Michelle, “Listen, I know I can help you, but I don’t know if this is the right time for you.” And that’s exactly what she’s thinking, too. I’ve just made it OK for her to speak the truth instead of hiding it. And a statement like “I want to go home and think about it” is never the truth.

MD: This is a good example of showing the patient how much you care by saying: “Yes, I can help you. I do this all the time. We just need to figure out how this works into your life.” The compassion in that statement of wanting to work with the patient is amazing. Dentists often tell me, “I don’t like selling, I don’t want to be in sales.” Well, there is no sales required this way. It’s no longer about whether or not they need this dentistry; it’s about accommodating them and saying, “I can fix you; how does this plan fit into your schedule?” It takes pressure off the dentist and the patient, too.

PH: It completely takes off the pressure. In dentistry, we use the label “patient-centeredness,” but every damn seminar I’ve taken that addressed a patient-centered approach has really been a dentist-centered approach. You’ve heard the adage “patients don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.” Is the way to show how much you care by doing a complete periodontal examination? I say that’s bull because it reinforces our own dentist-centered culture belief by imposing our beliefs onto our patients.

However, using the advocacy approach, we can be truly patient-centered because we’re asking, “When will it work for you?” The question is not if I’m going to fix the patient’s teeth; it’s when I do it based on that person’s lifestyle.

As a dentist, my desired outcome is for the patient to sustain a relationship with me because I know that 95% of the time, a patient won’t say yes to a $10,000 case the first time. But by sustaining a good relationship, that patient will come to me one or two or three years from now to do the work. In the meantime, I’ll do all the nickel-and-dime dentistry like cleanings and patching and fixing small things.

To the purist — the person driven by our dental culture — that’s supervised neglect. But I’ll go toe-to-toe with any proponent of that philosophy and say: “You take all the patients ready for complete care now; I’ll take all the patients who aren’t. In a few years, we’ll see who has the more vital practice.” It will be mine.

MD: But if Michelle doesn’t have any money, is the purist going to treat her for free?

PH: A purist probably won’t treat a patient for free, but there’s another way to treat patients — by being an advocate. Again, the role of advocacy is to ask “when?” And if she doesn’t have money or if the dentist is unable to do ideal restorations, the advocate will still help her find a way.

The way isn’t to achieve optimal clinical quality. If that was the case, everybody would do implants and fix bridge work. The way is to offer suitability to a patient who doesn’t have money, which may mean tooth extractions and full dentures. Then the conversation becomes about adapting. It’s not looking so much at the clinical result but finding the suitable result for that person.

When I have a patient who will lose his teeth because he can’t financially handle comprehensive care, I say something like: “Stanley, in the absence of comprehensive care, there is a high probability you’ll lose some or all of your teeth. I will help you in that process of transitioning from teeth to no teeth, and I’ll be sure to preserve your dignity in that process. And if or when you can replace the missing teeth, I want you to know that we’re experts at that, too.” You see, preserving the patient’s hope and dignity is more important than preserving each tooth.

Why? Because if I can preserve a person’s dignity, I preserve the relationship; and if I preserve the relationship, that puts me in a position to influence that patient for the rest of his or her life.

But, what if I get on my high horse and say, “Well, Stanley, if you can’t afford to do this, then you can’t be a patient in this practice”? Then I’ve lost all opportunity to influence him ever again. Chances are he’ll end up in the hands of a low-quality provider.

MD: Exactly right.

PH: So, there you have it. The patient education process is borne out of the cultural belief that our role is to change people. But I believe that our role is to understand people. And that happens primarily by understanding how dentistry can fit in their lives right now. It happens through a series of lifestyle conversations that replace those about the number of overhangs and malocclusions. We save those technical conversations for consent purposes, but not for case acceptance conversations.

MD: For some dentists reading this column, their heads will snap around because, from day one, they bought into this culture of having a technical conversation being one of the most basic truths in dentistry. What would it take to change that part of the culture? Could it ever happen?

PH: Yes, through articles like this, Mike. Realize that, at one time, the whole idea of anterior-guidance was ridiculous. If you go back far enough into dentistry, the movement of the mandible was allegedly believed to be controlled by posterior determinants, condylar angles and cusp-fossa angles. Remember that? Once the whole concept of anterior-guidance was introduced, dentists said, “Ah, OK.” And once they understood anterior-guidance, it made understanding the rest of the mouth easier, right?

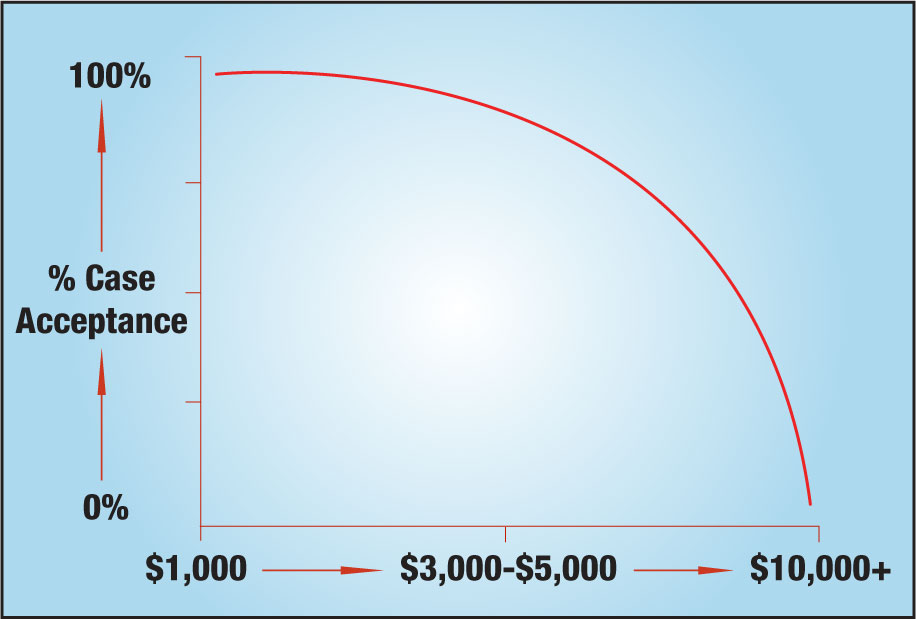

This is similar; it’s just a matter of getting to a tipping point. The first illustration (Fig. 1) shows the level of case acceptance relative to the size of the dental fee. The case acceptance stays fairly level at 80% to 90% or higher up to about the $2,500 to $3,000 fee level. Then after the fee goes above $4,000, it’s a straight nosedive down to $10,000-plus.

Now, the second illustration (Fig. 2) is the same graph, but this time, it has two arrows pointing up. On the left side, between $3,000 and the 0, an arrow points up indicating a rise in the dental IQ. On the right side, the arrow will be twice as big because, if the patients have twice the number of problems, they will need twice the amount of education. Historically, that’s what we believe, right?

But if that were true, why would the first graph be true? If raising the dental IQ was the key to case acceptance, then why does case acceptance go dramatically down when the case goes over $5,000 if it were, indeed, IQ-driven behavior?

Well, the truth is it’s not IQ-driven behavior. The doctor-patient relationship conversation is related to case acceptance because relationship-building in the dental practice is not based on patient education. The education model is a cultural trap that requires escaping from. For most dentists, that feels unnatural — like eating meat on Friday felt unnatural for me.

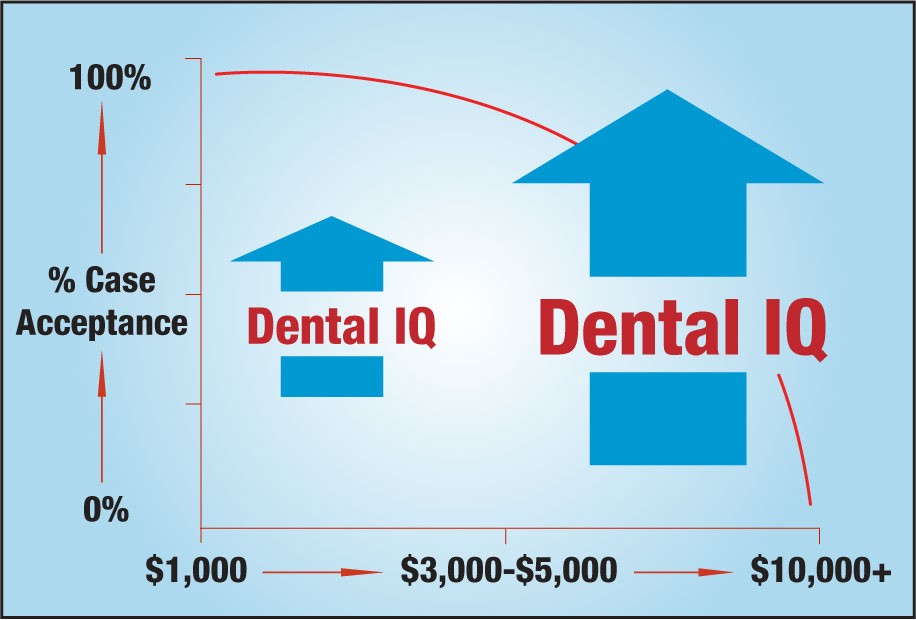

The third diagram (Fig. 3) is the crown-jewel of this article because it shows an inverse relationship to be aware of when dealing with patients. The horizontal axis represents the complexity of care as defined by the level of fee; the vertical axis is its relative impact on case acceptance.

When the case fee is low, like $800, $1,000, $2,000, the cultural belief of educating the patient serves us well. Patients with typically minor conditions need to be educated about those conditions because they probably don’t know they have them in their mouth. Raising their dental IQ becomes the driving energy for patients to say “yes” to the treatment plan. They get educated into readiness.

Now, let’s review the role of advocacy, which is the attitude that we help patients find ways to get their teeth fixed by saying: “I know I can help you, but is this the right time for you? Let me find the best way.”

The role of advocacy below the $3,000 level doesn’t operate that much because dental insurance, credit cards, CareCredit and third-party payers help ease the financial crunch. Also, small cases like that don’t take much time — two or three appointments — so they’re not as disruptive to the patient as long treatment plans can be. This tells us that suitability is not that big an issue below $2,000.

But as the case fee increases and complexity of care increases, the role of IQ decreases and the role of advocacy increases to the point where they cross. Then, at the $10,000 level, IQ plays almost no role at all and advocacy plays the dominant role.

MD: The first time I looked at that, I thought, “It seems counterintuitive for the dental IQ to be sloping downward like that.” But I took that to mean the higher the dollar amount on the case, the more obvious the problem’s going to be to the patient as opposed to back at $1,000, where they have two areas of interproximal decay. When you get to a $10,000 treatment plan, dental disability is a big problem. There’s no way a patient doesn’t know about it.

PH: That’s exactly right, Mike. Patients in that category are totally aware of their disability — not all the details but certainly the overriding condition. So, in the absence of disability, IQ dominates.

In the absence of disability, raising the patient’s IQ dominates relative to case acceptance. Why? Patients are not aware of the condition because disability isn’t a factor.

But in the presence of disability — and especially in extreme disability — the role of advocacy takes over. It’s more related to the size of the fee and the hassle of the case than to the depth of the disability. This is what should replace the blind pursuit of patient education — a situational approach based on current conditions and issues. For complex cases, a situational leadership model replaces the blind pursuit of education. That way, we don’t educate our patients right out of our offices.

MD: I see. We approach our patients with education, but when they don’t accept treatment, it stresses us and our staff. It’s a vicious circle started by this cultural belief that’s been around so long, no one knows who came up with it. But I think it’s been around the last 50 years.

PH: Here’s my call to action for your readers, Mike. They can enlarge Figure 3 or have it available to download on a computer. Then they laminate it and keep it in the lab or on the desk in the treatment planning area. When they’re about to see a new patient or present a treatment plan, they pick up this laminated illustration, look at it, and ask themselves: “What do I need to do here? Do I need to be educating this patient? Or do I need to be this patient’s advocate?”

Typically, dentists haven’t asked this question before because the culture hasn’t allowed for it. But what if the culture changed? How much easier would this be for the patient? How much easier would this be for the dentist? How much easier would it be to manifest clinical quality at the level deemed most appropriate in the presence of prosperity and the absence of stress?

MD: Yes, and what would it do for the perception of the profession as more people and dentists start to approach these types of situations this way? It’s not about the quality; it’s about suitability.

PH: The patients have always known this; the dentists are just now discovering it. When I teach suitability in workshops, many times dentists and team members approach me afterward and say, “You know, Homoly, this suitability thing you’re talking about is just good common sense.”

They’re right; it is just good common sense. And chances are that if dentists were never exposed to the existing quality-centered culture, the suitability-centered approach would evolve naturally in their practices. Why? Because successful suitability models exist in many other business models.

Unfortunately, most of us — me and you included, Mike — were educated out of common sense in the prevailing culture of dental education. It’s time to evolve our culture.

MD: What’s a good starting point for dentists to evolve their thinking along these lines, Paul?

PH: If your readers like this article, they’d love reading my book, “Making It Easy for Patients to Say ‘Yes.’” They can order it online at paulhomoly.com, or call my office at 800-294-9370 and my team will send it out.

And one more thing, Mike. Thanks for making the effort to spread the message by publishing this article. It’s a big part of evolving our culture and making everyone’s life easier.

To contact Dr. Paul Homoly or to purchase his book, call 800-294-9370, visit paulhomoly.com or email paul@paulhomoly.com.