The Effect of Low-Level Red Laser Light on the Healing of Oral Ulcers

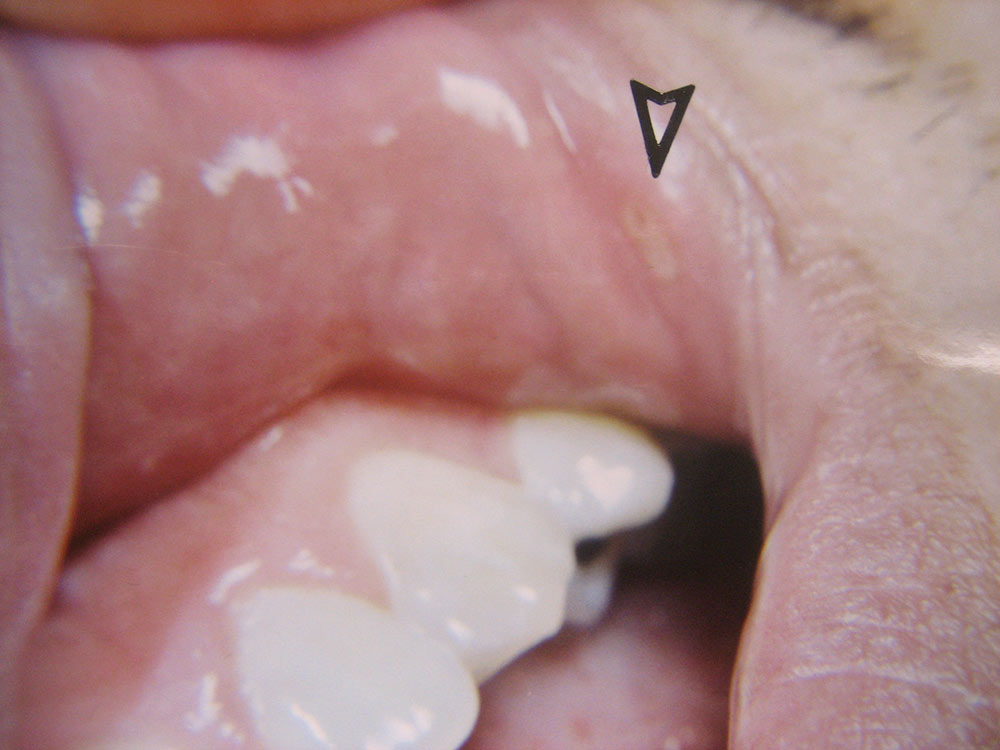

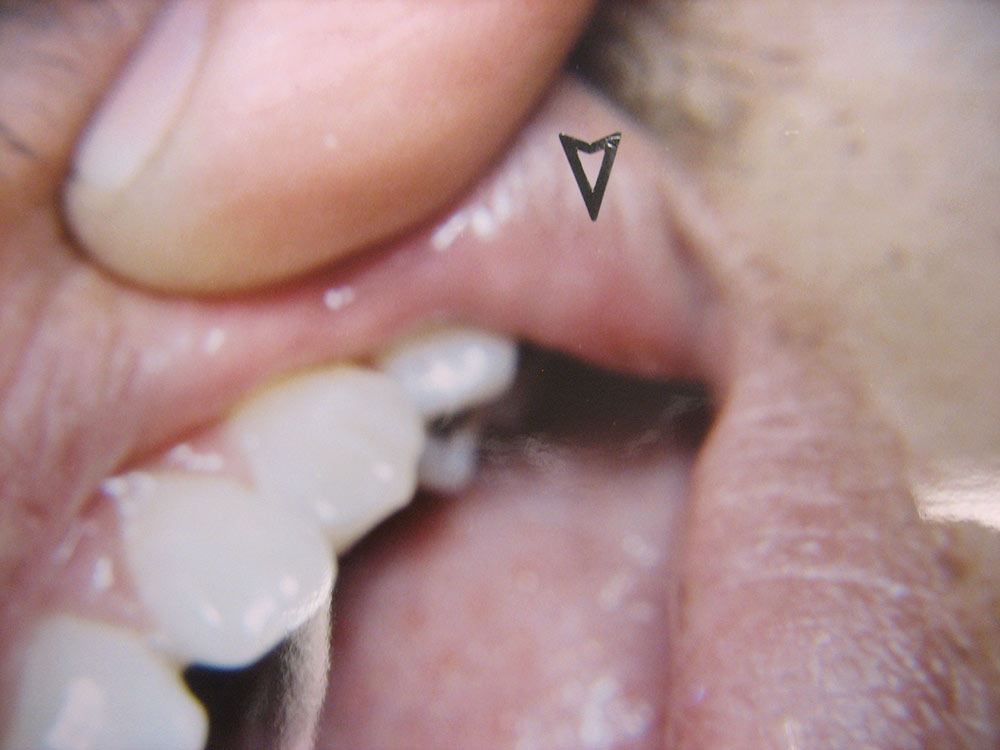

Note: Photos have not been edited, enhanced or retouched other than placing arrow figures.

Abstract

Low-level laser light at 30-second exposures (fluence=0.34J/cm2), from a red laser light pen (1.4mw, 680nm), increased the healing rates of a variety of intraoral ulcers in 69 general practice patients. Patients demonstrated that a single exposure to this light reduced 88% of mostly painful aphthous lesions to comfortable epithelized levels within two days. This compares more favorably than untreated lesions, which took five to 10 days for similar resolution. This study concludes that treatment of lesions using low-level laser exposures (the laser pen) is an effective and inexpensive method of oral ulcer treatment.

Introduction

Laser treatment of oral ulcers has been a recognized method of treatment for more than 20 years.1-8 Different types of lasers, power intensities and light wavelengths have been used with a variety of success.3,4,8 One of the most common lasers in use today is the red penlight laser. It operates at or below 5 milliwatts (mw) of power and produces light in the 630–690 nanometer (nm) wavelength range.2,5 These small, low-level lasers (LLLs) are readily available in numerous retail stores (e.g., dollar, department, hardware, office supply) for as little as one dollar. They are used as pointers, toys and play devices for pet owners.4

Lasers produce a coherent wavelength of red light, which encourages catalytic changes increasing the metabolism of reproducing epithelial and fibroblastic cells: the cells involved in mucosal and epidermal wound healing.1-5 By exposing most lesions to the optimum levels of laser radiation, healing is enhanced several times greater than what is seen in “normal” wound resolution.2,4,6,7,8 Most oral ulcers, such as caused by aphthous stomatitis, herpes, and traumatic episodes, will quickly heal when exposed to laser light in the 650–680nm (red) wavelength range.2,3,4

This study compares the healing rates of a collection of patient’s intraoral lesions, which are left untreated, to that of those treated with low-level red laser light. The purpose of this study is to determine how quickly optimum laser exposure would render intraoral lesions asymptomatic (comfortable) from the patient’s viewpoint. Reporting comfortable conditions surrounding the lesion is considered “healed” for this study.

The use of a single 30-second exposure of red laser light from a common <5mw laser light pen was sufficient to increase the “healing” rate (as defined by epithelization and the elimination of pain) from two to six times that of what was seen in the CONTROL group. The exposure to 680nm light significantly increased the rate of ulcer pain reduction and healing.

Methods

Patients reporting intraoral “sores” during routine exams were classified into two groups. The CONTROL group consisted of 100 persons. The LASER group consisted of 86 persons, of which 69 completed the investigation. The patients were told about this study, gave informed consent and participated. Each patient was selected at random on a first come-first record basis in a busy suburban private practice. Each lesion was recorded as to size, nature, sensitivity and duration. Most lesions were 1–3 mm in diameter and clinically diagnosed (e.g., aphthous stomatitis, herpetiform, trauma).

Any lesion presenting a rounded ulcer was included in the sampling. The CONTROL group’s lesions (100) were left untreated; however, the patient was told, by this author, that the “sore” would heal “within a week or so.” The LASER group’s lesions (69) received a single, 30-second exposure from a laser (OD China brand, generic penlight laser purchased at a local dollar store for $1) producing 680nm wavelength light at approximately 1.4 mw of power as measured by a Metrologic Instruments, Inc. (Blackwood, N.J.) photometer, Model 45-230. The laser spot size was 3 mm in diameter. Large lesions, greater than 3 mm in diameter, received a second exposure next to the first so that all areas of the lesion were equally radiated. This resulted in a fluence (exposure) of 0.34J/cm2 for each patient.

The patients were told that the laser light would “quickly heal the sore.” All patients were called the following day(s) for symptoms and to schedule an exam appointment. Half the sample did not present themselves for the post-treatment exams personally but reported over the phone that the “sore was/was not healed” (e.g., painful). Those who returned to the dental office were evaluated as to the extent of epithelization, resolution of tissue redness, tenderness and eating comfort. The appearance of full surface epithelization, a lack of tissue redness, and no sensitivity were the conditions necessary to classify the lesion as “healed.” For those who did not come for subsequent visits, their observations as to the “disappearance” of the “sore” and absence of tenderness were considered “healed.” Either the lesion was considered healed or it was not. There were no gradients involved in this classification or distinction as to whether the lesion was diagnosed as aphthous, herpetiform, etc.

Because the purpose of this study was to determine if the laser exposure was beneficial to the patient, the patient’s evaluation, substantiated by a percentage of confirming clinical exams (50%), was considered sufficient evidence as to the degree of wound healing. The reported comfort levels of the lesions examined on days after treatment closely correlated, in the degree of healing, to those patients who reported their symptoms and lay observations over the phone.

Results

The data from the two groups (CONTROL, LASER) were compared and statistically analyzed (p<.05, 95th confidence interval). Location of the lesions included the cheek (4.7%), vestibule (26.7%), lip (48.8%), pharynx (<2%), tongue (9.3%), palate (7.0%) and gingiva (2.3%). The most numerous lesions appeared on the lips and in the buccal vestibule.

The lesions’ diameter sizes ranged between 2 mm and 6 mm. The lesion sizes were: 2 mm (36%), 3 mm (30.2%), 4 mm (22.1%), 5 mm (8.2%) and 6 mm (3.5%). The most numerous sized lesions were 2 mm, 3 mm and 4 mm respectively.

Sixteen percent of the patients with lesions reported re-injury after their single laser treatment. These were not retreated but observed.

The time (in days) it took for healing based on clinical examination (50% of the sample) and patient’s self-assessment (via phone communication) ranged from one day to 10 days. Most of the CONTROL group reported/showed healing between six and 10 days from the first detection of symptoms (e.g., pain, ulcer). The LASER group was much different.

A lesion was considered “healed” when it appeared epithelized (covered with epithelial cells) and asymptomatic by patient’s own report. Basically, if the lesion visually appeared to be completely coated with epithelium (a variety of thicknesses) and did not hurt during normal function, then I considered the wound “healed,” though deeper epithelium and fibrous tissue had not made its full histological restoration. As mentioned above, only half the patients in the two groups participated in post-treatment exams. The other half of the patients were interviewed by phone (e.g., “Did the lesion appear covered? Was it comfortable?”).

One day after laser exposure, 49.3% of the LASER group’s lesions had resolved sufficiently to be classified as “healed.” After two days, 37.7% were “healed.” After three days, another 2.9% of lesions healed, followed by 4.3% on the fourth day. The remaining 5+% of lesions healed within the next three days. The larger lesions, and those which were reinjured (epithelium scraped off), were associated with longer healing times.

All patients reported pain as the main symptom of their lesions. An open ulcer, especially in the mouth, was quite painful in 100% of the patient sample. No mention as to the expectation of comfort (reduced pain) was made to the patients in an effort to reduce the placebo effect. When I asked, just after treatment, “How do you feel?” (I did not mention “pain” or “comfort”), 20% of the patients volunteered that their pain was “gone.” On the following day (24 hours later), 73.3% of the patients reported absence of pain. On the third day post-treatment, 6.7% of the patients reported to be pain-free. Over 90% of the patients reported to be comfortable (pain-free) one day after laser exposure. This contrasted significantly with findings in the CONTROL group, 90% of whom complained of some pain for at least five days. The LASER group had individuals who reinjured their lesions during biting and eating. These patients understandably had a longer recovery period.

The important issue in this study is whether the oral lesions, no matter what their cause, could be helped, from the patients’ viewpoint (i.e., elimination of pain and infirmity), by laser exposure. This study substantially demonstrates a positive effect of low-level laser treatment. Though perception of pain and “comfort” can be influenced by the placebo or waking hypnosis effect (up to 33%), the results of this study exceed this level of positive response and demonstrates that laser treatment for intraoral lesions is real and not simply psychological.

Analysis

This study analyzed 100 CONTROL and 86 LASER patients who had intraoral lesions from a variety of different causes. The most common were single aphthous stomatitis cases with a smattering of herpetic and trauma-induced ulcers. The use of a single 30-second exposure of red laser light from a common <5mw laser light pen was sufficient to increase the “healing” rate (as defined by epithelization and the elimination of pain) from two to six times that of what was seen in the CONTROL group. The exposure to 680nm light significantly increased the rate of ulcer pain reduction and healing.

A number of studies have reported a limited window of fluence (exposure) where healing will take place.1-5 Laser exposure exceeding these window limits will not increase healing but often retard it.2,4,6 A 30-second exposure, used in this study, seems adequate — no more, no less.2

Half of this study relied on the reports of patients who, for a variety of reasons, did not appear for post-treatment re-examination. Instead, they were phoned and interviewed as to their lay interpretation of their healing status. This may have compromised the accuracy of data in this study; however, most, if not all, patients could recognize whether the lesion was getting better as compared to getting worse and the lesion being painful as compared to being comfortable (asymptomatic).

The important issue in this study is whether the oral lesions, no matter what their cause, could be helped, from the patients’ viewpoint (i.e., elimination of pain and infirmity), by laser exposure. This study substantially demonstrates a positive effect of LLL treatment. Though perception of pain and “comfort” can be influenced by the placebo or waking hypnosis effect (up to 33%), the results of this study exceed this level of positive response and demonstrates that laser treatment for intraoral lesions is real and not simply psychological.

Low-level laser treatment from inexpensive (<$5) lasers has been known for many years.1,2 Unfortunately, this treatment has not been widely publicized or promoted. In part, this is because Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance has remained in the off-label arena and few, if any, commercial firms are willing to do the expensive testing needed to get FDA approval (est. cost: $250,000+). If a prospective firm wanted to market its laser product it would reflect the costs of testing, insurance and regulation, and could not compete economically with equivalent lasers purchased at dollar store prices. Why would the clinician pay several hundred dollars for a commercially FDA-approved low-level laser when one of identical qualities would be available in retail outlets for $1? Thus, we have no commercial low-level lasers available except in cases where high wattage, expensive dental lasers are used at powered-down fluences.1,4,6

Unlike more powerful laser systems (>5mw), normal LLL exposure is safe and does not require any safety equipment for staff or patient. Brief exposures to the retina and other organs have no record of producing serious injury, though long periods of exposure to the eyes (5+ seconds) can be irritating.3,5 Excessive exposure of lesions to LLL will not increase healing, but may retard the rapid healing effects of optimal exposure (e.g., 30 seconds).1-6

Low-level laser treatment is easy to do, safe, low cost per treatment (laser & batteries), painless and effective. Patients who have continuous oral sore problems may be advised to treat their own lesions using their own lasers under proper supervision (e.g., periodic exams). This treatment can reduce much pain and cost over a patient’s lifetime. All practitioners should use low-level lasers.

Summary

This study demonstrated that low-level laser therapy using a red laser pointer significantly reduced pain and increased the rate of healing in a variety of commonly experienced intraoral lesions. The ease of use and insignificant expense of this effective therapeutic device suggests that all practitioners become “laser dentists” and provide this mode of treatment to their patients.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Andent, Inc., for permission to reprint the photos contained in this article.

To contact Dr. Ellis Neiburger, call 847-244-0292 or visit drneiburger.com.

References

- ^Pinheiro A, Cavalcanti E, et al. Low-level laser therapy in the management of disorders of the maxillofacial region. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1997;15(4):181-3.

- ^Neiburger E. Rapid healing of gingival incisions by the helium-neon diode laser. J Mass Dent Soc. 1999 Spring;48(1):8-13, 40.

- ^Casigila J. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Gen Dent. 2002 Mar-Apr;50(2):157-66.

- ^Amorim J, de Sousa G, et al. Clinical study of the gingival healing after gingivectomy and low-level laser therapy. Photomed Laser Surg. 2006 Oct;24(5):588-94.

- ^Lask G, Lowe N, editors. Lasers in cutaneous and cosmetic surgery. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. p. 17-8.

- ^Ozcelik O, Cenk Haytac M, et al. Improved wound healing by low-level laser irradiation after gingivectomy operations: a controlled clinical pilot study. J Clin Periodontol. 2008 Mar;35(3):250-4.

- ^Sciubba J. Herpes simplex and aphthous ulcerations: presentation, diagnosis and management — an update. Gen Dent. 2003 Nov-Dec;51(6):510-6.

- ^Scully C, Porter S. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: current concepts of etiology, pathogenesis and management. J Oral Pathol Med. 1989 Jan;18(1):21-7.

Copyright ©2009 Ellis Neiburger. All rights reserved.