One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: Interview of Dr. Paul Homoly

I finally had the opportunity to sit down and talk with Dr. Paul Homoly about a topic that should be of interest to most dentists: profitability on typical crown & bridge cases. Most dentists have spent a fair amount of time thinking about their single-unit crown fee, and almost by default. It is probably one of the more productive procedures in our offices. But have you always assumed that productivity is linear for larger crown & bridge cases? If so, read on for some eye-opening perspectives.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: Paul, it’s nice to have you back at Glidewell. This is the first in-person Chairside® interview that we’ve had the opportunity to do together. Usually for the magazine, we interview people over the phone. It’s really nice to have you live in the studio, to be here together and to look at charts and information together. We’ve had fantastic response from your previous Chairside articles, and I’m really excited about what we’re going to talk about today. I know this is something that I struggled with when I was in private practice, and it’s a topic that dentists don’t spend enough time thinking about — it’s almost like a dirty word. And that dirty word is “fees.” This has to do with profitability and whether we’re ethical and whether we should be giving our services away. It’s scary for me to think that there are dentists who go through all this college, all this dental school and then take a big risk — $750,000 on a practice and staff it and practice for 30 years with the best intention to practice the best dentistry — but then never really give much thought to the fees, just kind of inherit the fee schedule from the dentist from whom he or she bought the practice. Thirty years later this dentist discovers that because his or her fees were set at the wrong place, after dedicating his or her entire life to helping patients, there’s nothing to show for it. Is this a scenario you commonly see?

Dr. Paul Homoly: Yes, absolutely. Or the dentist reads a magazine that says, you should be charging $830 for a crown, so that’s where he or she sets the crown fee. Talking about money in dentistry is always dangerous because money isn’t really part of our culture. When you think about it, how much did we study money when we were in dental school? And how often is money discussed from the main podiums in front of large audiences? Typically, the biggest groups and the biggest draws in dentistry have to do with pursuing clinical excellence. And the money is kind of like the dirty little secret behind it. But ask yourself this, Mike: How much excellence can a dentist produce if he or she is not profitable? How long can this dentist retain great staff members if he or she’s not able to pay competitive wages? What quality of dental laboratory must a dentist use if he or she can’t afford premium lab fees?

Money and profitability are almost an antecedent to clinical quality because the dentists who are most profitable are the same dentists who can afford good equipment, take time off for rejuvenation, use the best labs and pay the best salaries. So, for us to talk about fees — that’s really the first domino that must fall. Every dentist needs to be really smart about setting his or her fees. And without that wisdom, dentists won’t prosper.

Hufford Financial Advisors (huffordfinancial.com) partnered with Indiana University and the AGD in 2007, and together they surveyed 1,630 AGD dentists. When the surveys came back, Mike, 70% of AGD dentists were unable to retire and less than 10% expressed confidence in their investment decisions. Money isn’t a part of our culture. I encourage you to contact Hufford Financial Advisors to request a copy of the Financial Preparedness Study for Dentists.

MD: And the AGD is a totally voluntary organization — you don’t have to join. You get AGD credits, which count for, in a real sense, nothing. It’s kind of a bonus above and beyond — it goes toward your state credits. But to pursue fellowship in that academy, like I did, is really just about trying to do the right thing and being a constant student of dentistry.

PH: Becoming a better dentist.

MD: Wow, and AGD dentists are very focused on clinical quality. I think organized dentistry plays a small role in this; granted, we didn’t learn much about money in dental school, nor were we ready — we needed to learn how to control a handpiece and not kill someone. But even after graduation, I noticed that I received continuing education credit every time it was a clinical course. But God forbid I go to a practice management course where zero hours were offered. What message does that send to the dentist, when you literally don’t get any credit for learning how to run your practice?

PH: The message is that it’s not important or it’s wrong to learn.

MD: It’s wrong to learn.

PH: So let’s talk about fees. A typical dentist goes into practice, reads a practice management article and looks at a fee schedule. So you’ve got a whole list of numbers. You’ve got the ADA code, you’ve got the procedure itself and you’ve got a fee. And that fee schedule makes a lot of sense when you’re only doing one tooth at a time. So let’s say your crown fee is $800. You’re doing one crown. How much time, judgment, risk and skill go into doing one posterior unit, Mike?

MD: That’s pretty simple and straightforward. It’s not a buccal pit amalgam; it’s more difficult than that. But in the grand scheme of things, that single-unit crown is pretty basic. That’s something we do every day.

PH: It’s pretty basic. And if you look at the most common procedures a dentist performs, typically there are 10 to 12 procedures they’ll do 80% to 90% of the time. Most of the time, those procedures are done one tooth at a time. In these instances, working off a fee schedule makes sense. Now, Mike, tell me this: If you were to do two crowns, let’s say in the same quadrant, one right next to the other — does doing two crowns take you twice as long as doing that one crown?

MD: No, because I can anesthetize them both at the same time, I can break contacts on both of them at the same time with a bigger bur. Making the temporaries, they’re going to be connected, so there’s just a little bit of bis-acryl material.

PH: Take the impression at the same time. Take the bite at the same time.

MD: That’s all going to be at the same time, as well, as opposed to if they were in two separate quadrants. So, it’s not twice as difficult — maybe 1.3 times more difficult.

PH: What if there were three crowns in the same quadrant? Does the same apply?

MD: Yes, it would not take three times as much time to do three crowns, but it would be slightly more difficult.

PH: It would be slightly more difficult. I think the fee schedule, Mike, makes sense up to those 3 units per quadrant. If my fee for a crown is $800 and I do two crowns, it’s $800 times two. If I do three crowns, it’s $800 times three. That makes perfect sense.

Now, let’s jump to complex-care dentistry, Mike. Let’s say you’re doing 12 crowns. If you’re doing 12 crowns, chances are really strong that you’re going to change the plane of occlusion. If you’re doing 12 crowns, chances are really good that you’re going to change the anterior guidance, there may be vertical dimension involved, certainly changing condylar position. Of the anterior guidance, vertical dimension, plane of occlusion, condylar position, you’re changing three or maybe even four of those variables.

MD: Whether you want to or not!

PH: Whether you intend to or not (laughs). Now, let’s say you’re charging $800 per unit and you look at your 12 units. How much sense does it make to take your $800 per unit fee and multiply it by 12 for this kind of complex-care case? How much more complexity is there in the 12-unit case as opposed to 12 crowns done one at a time?

MD: It’s huge! It’s a much bigger difference. There is a much higher degree of difficulty in pulling off that 12-unit case, not to have the patient lisp afterward, be able to function well with those teeth without breaking them off in the anterior. There are a lot of factors involved. But as a dentist, you would tend to think: Well, if I did 12 single-unit crowns on 12 different people, that’s a lot of work! This 12-unit case is going to be great — I can do it all on one person at one time. But it fails to take into account all the systems that you’re changing and the degree of difficulty with successfully completing a big restorative case like this.

PH: Sure, it’s not only the degree of difficulty in terms of what you know to be true about occlusion, but it’s also the degree of difficulty relative to your planning. How much planning, preoperative planning, are you to do, Mike, for 2 units in the same quadrant? How much planning do you do for a case like this?

MD: None. You get them in the hygiene room before they go home that day and prep it.

PH: You put them in the chair, you can see the end result and you prep the case. Now, let’s say you were going to prep me for 12 units and you were going to change those four variables. How much planning would you have to do? How much time would you have to put into that case?

MD: Hopefully I’m going to put in a couple of hours ahead of time and get some lab-fabricated provisionals, which will add some expense, a Diagnostic Wax-Up. The patient’s expectations are going to be higher.

PH: You’ll be shooting photographs. You’re going to be taking models. Your team’s going to be pouring and mounting those models. You’ll be talking to the lab. What if the patient has gum issues or bone issues or missing teeth and needs implants? Now you have to get on the phone and call your specialist. How much time does that take, you playing phone tag back and forth? Sending the models back and forth? So there’s a huge additional component of time involved in these cases that doesn’t appear on your fee schedule. Know what’s not on our fee schedule, Mike? We get all these ADA codes, but you know what there’s not an ADA code for? Wisdom. We don’t charge patients for our wisdom.

On the flight from Charlotte to Orange County, I was reading the recent AACD journal accreditation cases. What magnificent dentistry is being done within that organization. I just love looking at those cases. But what I’d be really curious to find out is, how much profit are they generating? I wonder how much profit there is considering the amount of time they’re spending on incisal edge matrixes and reduction guides and customized incisal guide tables and custom shading.

MD: And that’s one of my pet peeves in journals, as well. They will show a direct composite, where they’re rebuilding a mesial incisal angle and a lot of the facial on an anterior tooth, and they’ll do a model, a Diagnostic Wax-Up and then a putty matrix of it to help build up the lingual of the composite. And I’m looking at all this stuff going, “This is insane! You’ve got to charge $1,000 for this composite to be able to do it like this,” which is fine if you can get it. But you’re right. I think the average dentist who looks at it and tries it would lose a lot of money, because we’re just charging this straightforward fee without any wisdom built into it.

PH: At the heart of advanced restorative dentistry is wisdom. What have we learned from the previous cases? For example, take the profession of law. You walk into a law firm and there are 50 attorneys. You’ve got the old ones and the young ones. Now, whose hourly fee is going to be the highest and why?

MD: You would think that those who have been there the longest would be the highest paid because they have seen the most cases. Especially if your case is a little bit more difficult, they might go, “You know, I tried something like this 14 years ago and read about it. Here’s what we need to do.” A young attorney might not have that experience or wisdom.

PH: Yes, so you’re paying lawyers a premium fee for their wisdom. Patient comes to you with a severe overbite, jaws clicking, periodontal problems, muscular problems and phonetic problems. That’s a difficult case. There’s a lot of risk there. A case like that requires a lot of wisdom. And really, I think the point of this article is or where I’d like to go is, how does a dentist take what they’re doing now and begin to assess: What’s the risk? How much wisdom do I need to apply? But do it in a practical way so you’re not guessing what your fees need to be. There’s a more objective way of looking at what the fee needs to be when you really understand your fee based on time, skill, risk, remake or change in patient medical history. Patient medical history is a real big one, Mike. Most rehabs are going to occur in a patient’s fifth or sixth decade of life. They’re going to be in their 50s or 60s. How many of these folks are still employed? So let’s say you’re going to do a big case, a $12,000 to $15,000 case. Even by today’s fees, sometimes it costs as much as $10,000 per quadrant depending on if you’re doing sinus elevations, bone grafts, implants, progressive loading, multiple units. If you take a high-fee case, a $20,000 case, on a person who’s in their late 50s or early 60s, that person is typically still in their income-producing years. And they’re kind of at the peak of their earning power. Now, you have a case that’s supported by posterior implants and fixed bridgework. The anterior teeth are all porcelain in the anterior guidance. What’s the probability that you’re going to have a problem somewhere in that case 10 to 15 years down the line, Mike? What’s the probability?

MD: Off the top of my head … maybe 85%?

PH: I’d say 100% (laughs).

MD: Well, I was putting a few weak-muscled patients in there, patients who won’t be able to chew anymore.

PH: The patient’s medical history changes. So, one thing we don’t recognize as we read the journal articles is what the case will look like 20 years from now. Show me that case when the patient’s sugar level is 250 and spinning out of control. Show me that case when the patient loses partial control of their hand or their eyesight starts to go and they aren’t able to clean their mouth.

MD: Or Sjögren’s syndrome patients, who run out of saliva and the teeth just deteriorate from underneath it.

PH: Or from all the medication they take. The difference now is that the patient is retired and they’re living off their retirement income. Now the case has a problem. Now you’re going to have to assign a fee. The fee to the patient now feels much greater than it did during their income-producing years. The point I’m making here is, when you initially do the case you cannot take shortcuts. If there’s a question between doing 2 units or 3 units of implant to support a bridge, use three. Will it be more difficult to sell the case with three implants? Yes, it will. But if you do not engineer the case for the lifetime of the patient, when they do have failures and remakes in their retirement years, you are going to have a huge management headache. Second point about fees is that, if you’re not doing many complex-care cases — let’s say you’re doing one or two or three a year, Mike — that’s what I call a hobby. It’s like the old guy that sits with the beret at the state fair building with the ship in a bottle. He loves it because he loves doing it, not finishing it.

MD: Isn’t that like somebody who goes golfing just three times a year? They go out there but they’re terrible at it. Can you be good at something you do three times a year?

PH: You can’t be good, you can’t be fast, but you can still enjoy it. So, it doesn’t make any difference what you charge for a case like that. Enjoy it, have fun with it. But I think for the majority of us doing complex-care dentistry and trying to make a living at it, if we’re doing one or two cases a month or one or two cases a week, the importance of setting the right fee becomes especially important. Without the right fee, what will happen with complex-care cases? Your gross will go incredibly high but your net will begin to dip. You’ll feel like hell, you’ll feel more stressed, and the overall quality of your practice and other cases will begin to suffer, too. The big cases will pull the rest of the practice down.

MD: How confusing must that be for a dentist to see the gross go up, be high-fiving people: “We had a great production day! Woo hoo!” And then the net goes down so far it becomes depressing.

PH: That was me. My first 10 years in practice, I pursued quality. I was like a sled dog chasing a rabbit. I was on a quest for quality. Yet our gross was incredibly high. I think my practice at one time was in the top half-percent of solo practitioners’ productions. But my net, hell, I was embarrassed to talk about it. I was doing these big implant cases, but to tell you the truth I was secretly praying for a couple of simple 3-unit bridges to walk in so I could pay my bills. And you know what? That’s another dirty little secret — these big cases often don’t yield the profit that they really need to.

MD: But dentists want to chase the big cases, right? They go, they take courses: “If I get just one big case per month, it will pay the bills.” Really, in terms of profit, what you’re saying is, for a 12-unit case, where you’re almost doing that full maxillary arch, the dentist would actually be better off doing four 3-unit bridges on four different patients in terms of profit than one 12-unit case on a single patient?

PH: Absolutely. Because you can do four 3-unit bridges without having to spend the time and planning that you do with one 12-unit case. You don’t need to think about it that much. You know, ultimately where this conversation is going to lead is that when you’ve got six or more units and you do the cases right, Mike — I’m talking about preoperative photos, preoperative study models, incisal edge matrixes, customized provisional temporaries, using temporaries as diagnostic tools, putting in nightguards, corrected equilibrations and follow-ups. When you do the case well, my studies have shown that typically you’re going to need to add 40% more to the fee over your fee schedule. So, if you’re $1,000 per unit and you’re doing 6 units, in order for those numbers to work out well for you, you’re going to need to add 40% to that fee. And if you’re 12 units or more, Mike, in order for those units to work out well, you’re going to need to add 70% to your fees in order for that case to be profitable.

MD: Wow. And you’re talking about fees that are already in place for 1-, 2- and 3-unit crown & bridge? This isn’t somebody who hasn’t raised his or her fees for eight or nine years and has an artificially low crown fee; this is somebody who has their crown fee in place for the 1- and 2-unit cases. They still need to add more than 70% for a 12-unit or more case?

PH: Right, because dentists must consider the time invested. It takes time to get study models. It takes time to pour the models. How much time is spent on a good Diagnostic Wax-Up? You learn how to rehabilitate a case while you do the wax-up, not as you’re prepping the teeth. That’s where the wisdom is manifested. You don’t need to do that with simpler unit cases. How many dentists spend hours and hours at their office after business hours waxing-up cases, trimming dies, looking through microscopes, and going through trial equilibrations without charging the patient for it? That’s unsustainable behavior. And that’s not something you see or hear in the journals — people don’t talk about it.

MD: Or what’s even scarier is, because they’re not doing that, they’re not adding 70% to those bigger cases. They’re not doing any prep work, they’re just doing run and gun: prepping all the teeth and putting the temps in. That’s where the risk will come back to bite you.

PH: I can’t even address that situation because if you’re doing big cases and you’re not doing the right wax-up, you’re not doing the right temporaries, you’re just slamming stuff in and hoping people will get used to it, then you’re going to end up with skinny kids, number one. The probability is going to come back to eat you. Number two: You’re going to end up moving several times in your career because people are going to come back mad and you’re going to end up with a remake legacy that you’re not going to be able to deal with.

MD: So plan on taking state boards in several different areas, is what you’re saying. That’s a good plan.

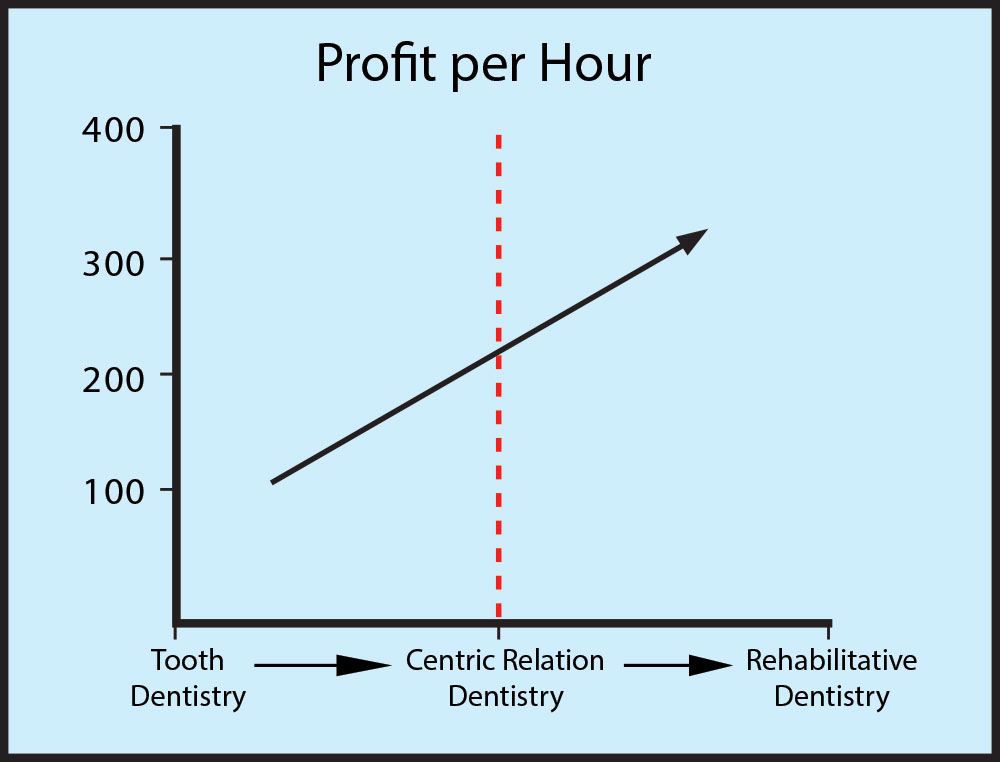

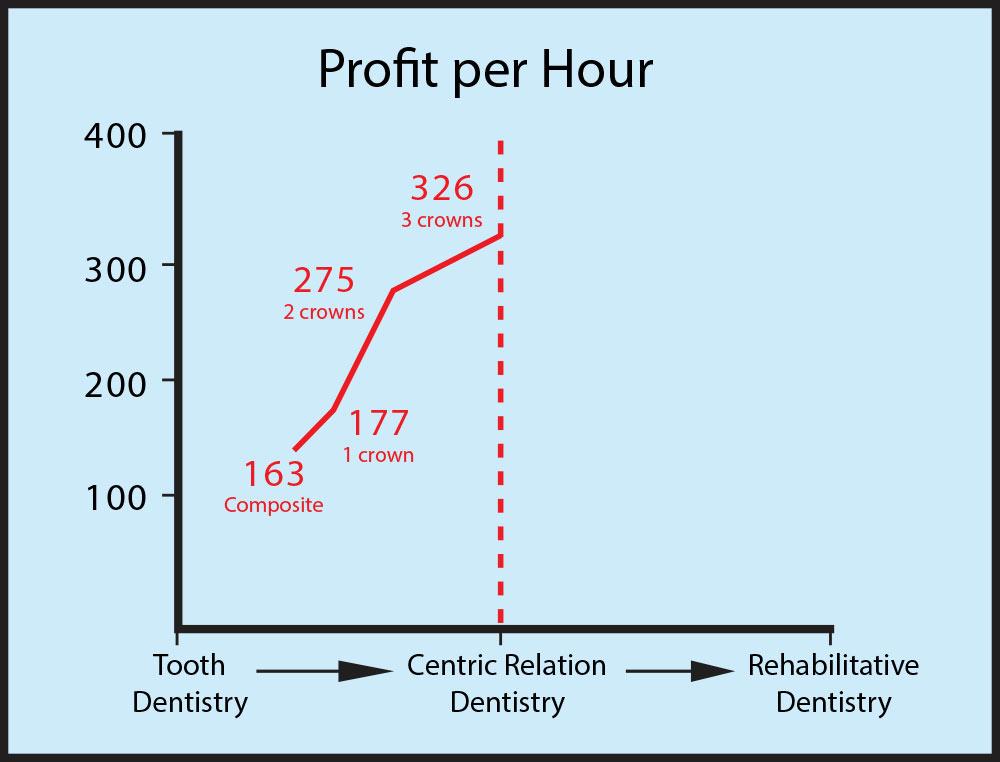

PH: Let’s look at it from a standpoint of some illustrations. Figure 1 shows the complexity of care all the way from the left, which is tooth dentistry, all the way to the right, which is rehabilitative dentistry.

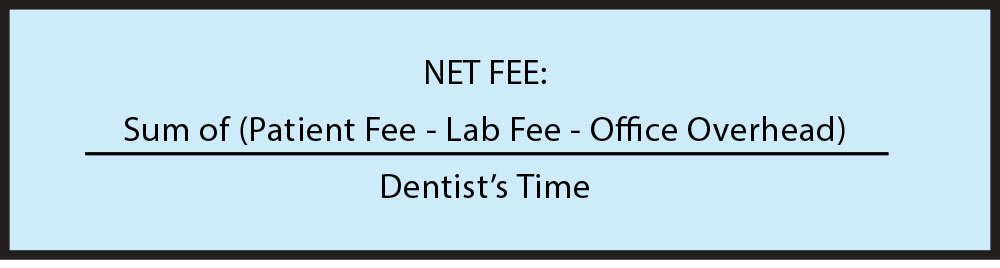

The vertical column represents that fee per hour and consists of the patient fee minus the lab fee minus office overhead, divided by time.

Typically when we’re in the tooth realm of 1, 2 or 3 units, the level of profit is fairly modest, but it escalates. The common belief in dentistry is, as I do 8, 10, 20 units, this profit yield should continue on a straight line. That’s the belief.

Now, when you actually put the numbers to it, it looks like this: Single posterior composite fee, $163; posterior ceramo metal unit with a profit of $177. If you do 2 units in the same quadrant, as you were saying earlier, Mike, you can get it done in not twice the time but probably 1.3 units of time. So the profit jumps from $177 to $275. And if you do 3 units in this same quadrant, the profit jumps up to about $326 (Figure 2).

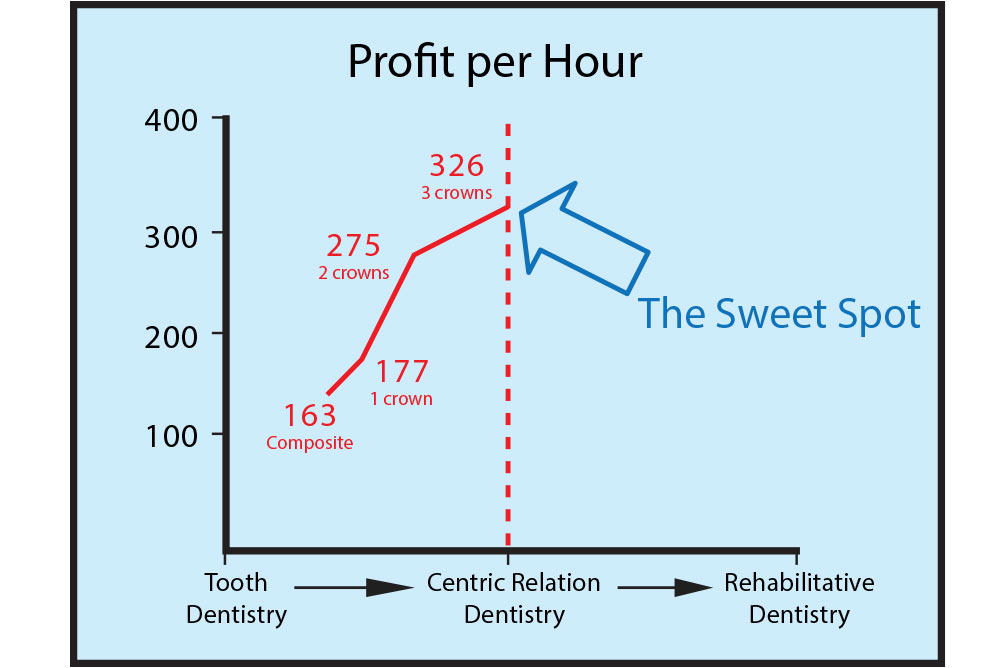

The three posterior units in the same quadrant at the same vertical dimension, plane of occlusion, condylar position, incisal edge position, where you’re not changing those variables, 3 units in the same posterior quadrant represent what I call “The Sweet Spot.” That is: the highest net fee per hour most general dentists can generate. It’s the sweet spot (Figure 3).

It’s like the spot on a golf club, Mike: You go on a golf course, you pick up your 6-iron, you happen to swing well and click! You can tell when that ball hits the sweet spot on the club. It is the maximum flight of the ball. It is the maximum performance of the ball with the minimum exertion of energy. Three units in the posterior quadrant provide maximum results, in terms of profit, with minimal energy.

MD: And I bet most dentists know that on a certain level. They couldn’t give you numbers. They certainly couldn’t quantify it. But you might say to them, what’s your favorite thing to do? And they might say, “I like a good 3-unit bridge.” And we have 3 units here in the sweet spot, the profit per hour, but we’re only prepping 2 units, so that might be the sweet spot. You charge for the pontic, and life is good. Greatest determination ever: that we can charge the same for a pontic as an abutment. So I think most dentists would probably know that on a certain level. They couldn’t articulate it, but they would know on a certain level, that’s my favorite thing to do. And that’s probably why.

PH: When you take out the fee schedule and say, “Well, my crown fee is $800. So, for 1 unit I’m going to charge $800; for 2 units I’m going to charge $1,600; for 3 units I’m going to charge $2,400,” that progression makes sense. Why? Because it is very low risk, very low remake and low planning time.

MD: So, that actually works? To actually take your crown fee and multiply it by two or three actually works in these lower-risk cases?

PH: Absolutely, and for many dentists, that’s where 80% to 90% or more of their dentistry exists and where the fee schedule makes sense. There’s all sorts of journal articles about what to charge for a single-unit crown in the Southwest versus the Northeast, and how much time is taken. And all those are valid if the dentist is doing 3 units or less. Now, all of that breaks down when the case gets complicated. All of it breaks down when the dentist has to change vertical plane of occlusion, condylar guidance or incisal edge position — I sound a bit like a broken record here. But those are the big variables of a case. Those variables, in addition to medical factors, especially when you’re dealing with dental implants, where host resistance is a huge component. Then factor in aging components, risk factors that are inherent to the dentistry, the intraoperative remake. You made a statement earlier, before we started about veneer cases — what percentage of them need to be remade because of the contact.

MD: Or a single unit will need to be remade within an 8- to 10-unit case.

PH: An 8- to 10-unit case of single unit would need to be made, so that’s 10% right there. I call that an intraoperative remake. Now, your laboratory may not charge you for that but there’s still the factor of time involved.

MD: The patient has to come back again, have it put on. It’s another 45-minute appointment.

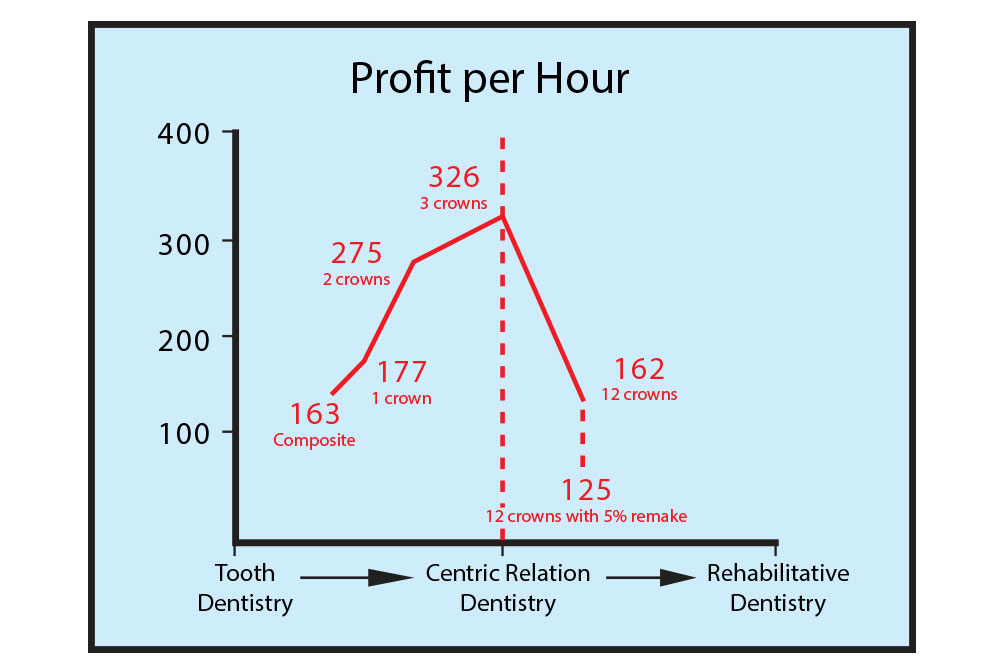

PH: Another 45-minte appointment. Remember: profit per hour is that per hour. It’s divided by time. So you have intraoperative remake that is a factor when you do your 12-unit case. You have complexity to the case relative to the patient’s musculature and neurophysiology. You have a change in the patient’s medical history that can ultimately make a case turn sour. Plus, all the time and planning. All of the photographs and models will oftentimes — if you take a 12-unit case now and you take your unit fee at $800 per unit and multiply it times 12, you’re going to be 40% to 70% too low if you base it off a fee schedule (Figure 4).

MD: Wow. So, the crown fee is reliable if you’re doing one crown, two crowns or three crowns. But if you have a great case that walks in the door that you’re excited about, if you take that crown fee and multiply it times the 12 crowns, you’re saying there’s almost no way on a case as complex as that to make the same per hour if you were doing two crowns.

PH: That’s right. You’re better off doing 2 units at a time on six to eight different patients. Or even on that patient!

MD: Even on that patient. Spend six years doing two crowns at a time. Your kids will be fatter, right?

PH: Absolutely right. And that is something dentists miss all the time. I missed it early in my career, Mike; I’m sure you missed it, too. We were so in love with the process of fixing teeth that we didn’t really see or feel the bigger picture. When dentists hit their 40s, their backs begin to get sore, their eyes begin to go. You can’t make up for lost ground very easily. You are not the practitioner from 40 to 50 or 50 to 60 that you were from 20 to 30 and 30 to 40. You won’t have the same energy, you won’t have the same eyesight, and you won’t have the same stamina. The earlier dentists learn to set their fees relative to complex care, the easier it will be for them to accumulate wealth, to be able to build a profitable practice and to have what they really deserve. The practice of dentistry takes a lot: We capitalize our own businesses, we hire the people, we manage the facilities, we do the dentistry, we empty the plaster trap. We do a lot of things. And improperly set fees can drag you right down.

MD: That makes a lot of sense. So, to do that 12-unit case correctly, the 12 times the single-unit crown fee is the baseline.

PH: That’s right, that’s the baseline. You said it earlier, Mike: That’s your base pay. Now you look at, where should the fee be? When you look at the sweet spot, I’ve got it set at about $326 per hour. And that’s net fee per hour.

MD: Define net fee per hour for us.

PH: Net fee per hour is the patient fee minus the lab fee minus the lab overhead divided by time.

That $326 represents my net fee per hour when I’m doing 3 units all in a posterior quadrant. That’s the safe sweet spot right there. Now, when we cross the line and start doing rehabilitative dentistry, where we’re doing those four variables, now our net fee has to be greater than that sweet spot. Here’s why: Because if it’s not greater, we’re not profiting at the level that the risk demands. If you were an investor and you were to invest in something that is safe, like U.S. Treasuries, you would accept a lower return on investment because you’re not making a tremendous risk in the marketplace. But what if you were invested in a very volatile, risky investment? What type of return would you expect there based on risk?

MD: It’s got to be higher.

PH: It’s got to be a lot higher. When you start doing rehabilitative dentistry, you’re making an investment in a risky business. Therefore, your net fee per hour must be greater than what you’re doing on a lower- or no-risk case.

MD: In one sense, these complex cases are sort of volatile. There are just more things that can go wrong versus a single-unit crown.

PH: Mike, they always go wrong!

MD: It’s just a matter of getting it right in the end!

PH: That’s right! Even in the end, it can’t be right all the time. I did rehabilitative dentistry for 20 years, and I can think of very few cases. You sit down and treatment plan a patient. Let’s say you’ve got 12 units of root canals and implants and all sorts of moving parts in the mouth. You treatment plan that case out, you get your treatment planning form out and you color in all the teeth, color in all the arrows, you get it all done and you add it up. Now, what’s the probability that the treatment plan is exactly what you’re going to do at the end of the case? It’s about zero. There’s always stuff that will change. We’re going to pursue excellence. This is a great treatment plan and I practice in a very excellent way and this is the way it’s going to be. Dream on! There’s no amount of excellence that’s going to compensate for change of host resistance or act of God or anything else that goes on.

MD: It reminds me of that old thing, how a plane flying from Los Angeles to Hawaii is off course 99% of the time, constantly correcting for the winds. But hopefully the pilots get that plane down where it needs to be in the end. It’s a constant matter of adapting to the environment. Buildups you have to do that you didn’t foresee, that you didn’t plan on. Composites falling out and you’ve got to do some filler, and now that post is coming out.

PH: Or you laid a flap and what looked like good bone now is mush and you have to graft the area and allow it to heal. Or you have a post-operative complication. You place three or four implants. I remember earlier in my career, we weren’t as sophisticated about our flap management. We’d place three to four implants. We’d come back in about 10 days or so, pull the lip back and you know what? Some of the cases, the flaps would open and we would see the tops of the implants, and that’s when I would feel the heat — the heat from my stomach come up, like swamp gas settling on my face.

MD: That’s going to take a few minutes off of your life! And you weren’t being compensated for it, were you?

PH: I wasn’t being compensated for it. So how do you fix a case like that? You don’t. You let it granulate in. You see the patient for 15-minute increments every two weeks and it’s like watching a death march. And the longer you look at the patient like a little thermometer, your profitability is going down. Now you’re just hoping to break even.

And specialists wonder why more dentists don’t refer dental implants or complex-care patients. Because oftentimes the general dentist is much more profitable from the sweet spot on down, from 3 units on down, than they are with these big god-almighty cases that sometimes can take years to complete. The dentist that refers a lot, Mike, is the dentist that has abundance in his or her practice. The dentist who’s doing a lot of bread and butter dentistry, their bills are paid, they’re making their profit goals, their staff is happy, they have a good facility, they feel good about the dentistry they’re doing. Abundance drives referrals. That’s a different topic we can touch on another time — the specialist-generalist relationship.

MD: Right, but the point being that they need to be well versed and confident in their sweet spot dentistry to be able to think about referring out the comprehensive dentistry.

PH: That’s right. And when you sit down and you treatment plan your big case, you’re going to add fees to different areas of the case where we normally don’t add fees. Number one is going to be in consultation. Consultation with physician, consultation with specialists, consultation with laboratory, consultation with other dentists, consultations with pharmacists — whomever is going to be involved in the case, consultations take time. I would consider adding 5% to 10% to my fee for consultations. Second thing I would look at is occlusal analysis. What does that mean? Well, it means that you’re at home or you’re at the office, you’ve got nobody else there, the study models in your hand, you’re on your articulator thinking. This is where you’re manifesting your wisdom. You get compensated for that. And occlusal analysis, with the accompanying Diagnostic Wax-Up and creation of templates, that’s got to be worth at least 20% to 25% of a premium fee. Another thing we miss is equilibration. Mike, I believe that equilibration is one of the finest arts in dentistry: knowing when to stop; knowing where to grind. Knowing when to grind, when not to grind. Knowing when enough is enough. How much do we need to adjust bites long-term on these rehabs? We’re always kind of touching things up. And equilibration is another 10% to 15% on these cases. So, if you look at the different areas that we typically don’t charge for, those can add up to 40%, 60%, 70% over those fees that one would charge based on their fee schedule. You want to end up with your fee for the rehab case now. You want to end up where your profit — when you fee a case, plan on a 5% to 10% intraoperative remake. Mike, you work here with Glidewell. You see 20,000 units a month go out the door. Give me a sense: What is the average remake rate of the dentists you work with?

MD: If you combine everything — removable, fixed, all the different things we do — it’s around 6.5%. And that includes me being in the lab. My personal remake rate here at the laboratory is about 6.5% — and that’s healthy. We see dentists whose remake rates are 30% to 35%, and there’s something wrong there. I was looking at an account the other day because we got a goofy impression, the most insane impression ever. It was literally about 8 cm and it was an impression of just one tooth for a crown on that tooth. There was no tray. It was an impression of the prep and about the occlusal third of the opposing tooth, nothing else. It was crazy. And the department said this dentist sends that in all the time; that’s his standard impression. And when I looked up his remake rate, it was less than 1%!

PH: Well, that may not be good either.

MD: That’s my point! He’ll cement anything. In fact, we have records. We’re relatively sure he once cemented a crown intended for one patient on another patient. I suppose he looked at the inside of it and prepped the tooth to match it; we call him “Dr. CEREC” now. It’s just as bad to have a really low remake number because it shows you don’t have quality control. You know, there are 63 steps between when the impression is taken and the crown is delivered. A lot of it has to do with the provisional. When the temporary is on for two weeks, nothing good happens. Nothing good happens during those two weeks except the patient’s pterygoid muscles heal from the lower block that you gave them, if you’re still giving lower blocks (which I hate to do). But nothing good happens. Things shift, things move around. Bacteria gets under the temporaries and teeth get hypersensitive. They erupt. So there’s a number of reasons why there would be a remake rate around 6.5%. CAD/CAM has the opportunity to lower that a little bit. But that’s what it is and that’s what it should be. It should not be 35% and it should not be 1%. So, 6.5% is right about where it should be, if you’re honest about evaluating dentistry intraorally and giving people quality restorations.

PH: So the smart thing to do as a practitioner is, when you put your final treatment plan together, factor in additional cost for consultation, occlusal analysis, diagnostic provisional, equilibrations, nightguard, post-operative adjustments — then it makes perfect sense to factor in another 8% to 10% for intraoperative remake. And the patient accepts that fee.

Now, Mike, the patient has paid your premium fee. You’ve got your premium fee and now you get into the case. What’s your attitude now about an intraoperative remake? How much stress does it cause you now?

MD: Just one? Is that all I have? We planned for three!

PH: Right, if you’re planning for 10% and you have 5%, you don’t have the stress and the anxiety of the case hanging over you. If you’ve underfeed the case, everything extra you do is just another straw on your back, in terms of your profitability. If your case is feed with the adjustments made to risk intraoperative remakes and these aspects that I’ve been talking about, now when the remakes or the failures or the breakdowns or the changes in the patient’s medical history occur, it doesn’t become a stressful event for you, not nearly as much. You might feel bad that you need to redo something, but economically it isn’t hurting you and the team and your ability to sustain the practice. Lack of profitability is not sustainable behavior. And we see it all the time with these doctors who come back from the institutes — and I’ve got nothing against the institutes, I teach at most of them — but they come back with this idealistic attitude that as long as you pursue excellence and you trim your own dies and you use microscopes and you have these special gizmos they told you to buy that you’re not going to have problems with your cases. You are going to have problems with your cases. And that’s normal. My point here in this discussion is to charge for them.

MD: You’re right, because losing profitability is not a long-term strategy. The lack of profitability would absolutely get in the way of quality dentistry, unless you’re independently wealthy from an outside source and you’re doing dentistry as a hobby.

PH: If a dentist is not profitable and then reaches his or her 50s or 60s and they begin to think about bringing in an associate, now this tendency to suffer from lack of profitability brings an associate to transition into the practice, to buy the practice. If the practice is not profitable and the dentist is buying into it, that ushers in a whole other layer of complexity relative to: 1) the failure of the buy-in; 2) the dentist is not modeling good profitable behavior. So we have this lack of profitability culture, this legacy that is passed on from dentist to dentist to dentist, which is a shame.

Several years ago, Reader’s Digest magazine had a phantom patient that went from office to office. And I forget the situation, but apparently the fees that came back ranged anywhere between $2,000 and $25,000. One of the journals had the patient’s X-rays and all that. And I looked at that case and thought: The only dentist who got it right was the dentist who charged $20,000. Because he was the guy that took the models, was putting them in the splint, who did the equilibrations, who did the case well. And the dentists who cried about it were the ones losing money because they didn’t know how to set fees, and they thought this guy was a bandit. He’s not a bandit; he just knew what he was doing. Big difference there.

MD: You mentioned to me a study that you have in which more than 100 dentists participated, doing the same type of thing as the Reader’s Digest article. This is probably long overdue in dentistry, because dentists had a knee-jerk reaction to it: Oh my gosh! It’s not like in dentistry we take an FMX into a machine and then out comes a treatment plan with the fees already on there. It kind of would be nice in a sense: “Your case is going to be $20,000.” And the patient gasps and we just say, “It’s the machine! We all use the same one. Go to the dentist down the street and he’ll tell you the same thing.” Because now you’re taking the emotion out of the dentist and the guilt about telling somebody they need $20,000 worth of dentistry. So, it was a study that was done by some friends of yours, where they had 126 dentists treatment plan an 8-unit case, with some other things that needed to be done. There, you also saw fees all across the board. Tell our readers about that study.

PH: Ken Mathys and I teamed up years ago, and taking what I’ve described as this right-fee solution, that’s the brand we use for this. And that’s taking your fee schedule and proportioning it so that the fees of different procedures you do make sense to each other. For example, the care and skill and judgment of doing a simple posterior crown may be less than the skill needed to do a Locator® Bar Overdenture (Zest Anchors; Escondido, Calif.). So there’s going to be a difference of skill between those two.

Ken is a CPA, and he runs a company called Dental Practice Advisors (dentalpracticeadvisors.com). I asked Ken to use his CPA stamp-of-approval on the spreadsheet that I gave him. That is, take it up to the CPA level of accountability. Well, he and his team did a wonderful job. What they did in 2006 is take 126 of their best clients, dentists who are working under a financial plan and who care, and they gave each of these dentists the same 8-unit case. And this 8-unit case involved changes in vertical dimension and anterior guidance and those sorts of things.

Ken worked it out; he worked with another dentist to put this case together, all the different appointments, what they would need to do. Then he gave this sample case to 126 dentists and asked them: How much time would you spend doing it and what would you charge?

The numbers these dentists came back with were all over the place. Fewer than 15% of the dentists made any change in fee relative to changing those four variables — anterior guidance, vertical dimension, condylar position or incisal edge position.

MD: So, essentially, they just took their crown fees and multiplied it times eight?

PH: Exactly. Eighty-five percent of the dentists did that. When you look at the profitability aspect of it, close to 20% of the dentists were netting out less than if they were doing single-unit posterior units.

MD: Wow, talk about a kick in the groin.

PH: It’s amazing. When you see the math you just want to shake your head. The big culprit is time. The biggest mistake a dentist can make is to look at his profit and say, I need to find a cheaper lab. A cheaper lab is not the answer. What you want is a lab that can get the job done right the first time. The answer to many of our profitability issues has to do with time and leadership. Time is the divisor. That is, if you use two hours instead of three hours, that’s a huge difference in profitability. Time is a big culprit. Ultimately, Mike, you arrive at a fee that might be 40% to 70% more than you would normally charge.

MD: What does the average dentist say when it’s suggested to them that they need to do that? Do they say, “I can’t do that”?

PH: Exactly. They look at it and say: “I have a hard enough time selling a $10,000 case. Now you’re saying that it’s a $17,000 case?” Well, it is based on the amount of time and risk that you have to do. And they say, “Well, I can’t sell that.” That’s where it goes into leadership. That’s when the dentist needs to look in the mirror and say to him or herself: “What do I need to do in how I present care to patients? How do I train my team? How do I run my facility? How do I earn the right to charge $17,000? How do I, as a practitioner and as a leader, signal to the marketplace — my patients, my team — that we’re worth it?” Because the difference between the $10,000 and the $17,000 reconstruction, when it’s done well, is huge. You can’t be doing reconstructions half-assed, because it will come back to haunt you. So the higher-fee cases are more difficult to sell. Case acceptance for the high-fee case is something that I have focused on for the last 20 years of my life.

MD: Now, in those 20 years that you’ve been focusing on high-fee case acceptance, is there a huge difference between case acceptance for a $10,000 case and a $17,000 case? Don’t they both sound relatively expensive to the patient?

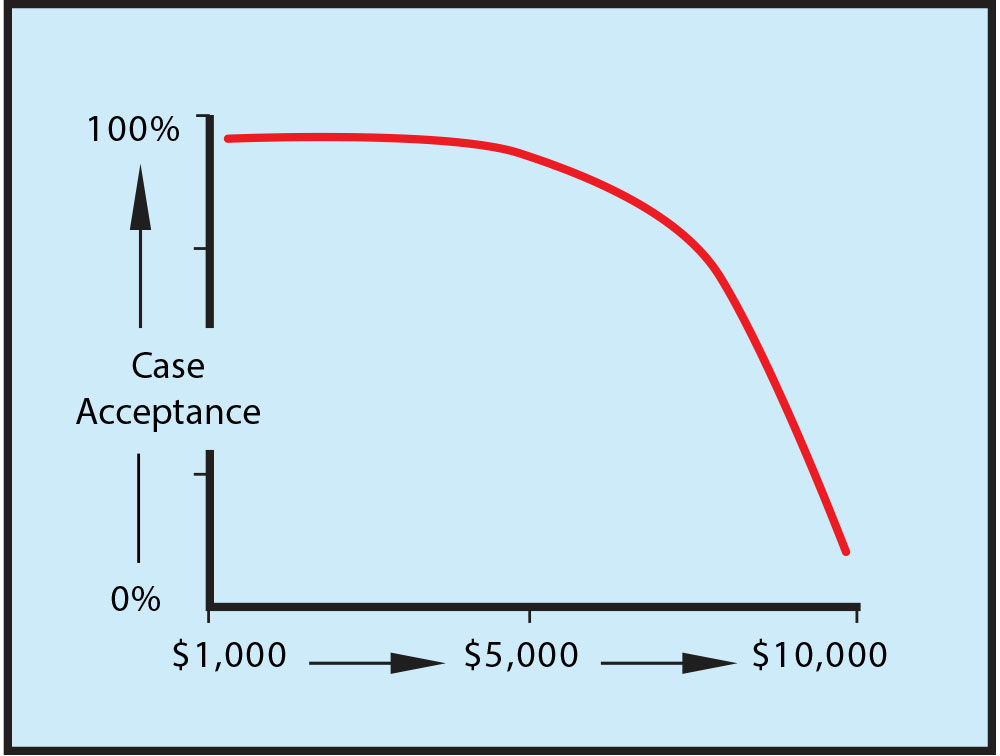

PH: Absolutely, yes. You know there’s a case acceptance curve, where case acceptance is real high when the case is really low (Figure 5).

But as you cross that $5,000 to $6,000 mark, that’s where I see case acceptance drop down. Is case acceptance that different between the $10,000 and $17,000 level? Not really, but enough psychologically for the dentist. Not so much in the patient’s mind, but it is in the dentist’s mind. So factoring in proper case acceptance dialogues and essential conversations that you have, those conversations need to be entirely different at the $10,000 level up than at the $5,000 level down. And that’s been the topic of some of our other articles.

MD: Yes, we’ve talked about that before. So a dentist who’s reading this or listening to this and realizes, wow, I bought this practice 13 years ago and I just took over at whatever Delta-approved fees the previous dentists had and we’ve tried to make increases every year based on our ZIP code as time went on. Maybe I should take a closer look at my fee schedule before I get too much farther into this to see if my fees are in the right place and make sure that when I’m operating at the sweet spot, I am making the net profit per hour that I deserve.

PH: I’d contact Ken at Dental Practice Advisors. For years I did the fees and analysis, but they are far quicker at it and more complete. What they’ll have you do is submit two or three of the large cases you’ve done, your fee schedule, and your profit and loss statement. And they’ll look at it comprehensively. They’ll look at how much money you need to live; that’s where they’ll start. How many days do you want to work? How much money do you need to live? This will create the profit per hour that you need to make. Then they’ll look at your practice overhead and your fee schedule. They’ll adjust your individual fee schedule such that the fees are balanced up to that 3-unit level. Then they’ll look at your complex-care cases to help you look at and see, what is the profit you have? And what’s amazing, when you come back from a profitability analysis or a fee analysis like that, you come back with some hard data on a piece of paper. Now you can sit down with your team and say: Listen, when we did Mrs. Smith, that case where we all pulled our hair out, we made less on a per-hour basis than when we’re just fixing individual teeth. When you can see it in black and white, Mike, that becomes a great leadership tool. It becomes more real to everyone. And now, I can sit down with my dental assistants and say: You know, you’ve been asking for a raise the last several months. See this profit point that we have right here? In order for me to give you a raise, we’re going to need to move that profit point up. A lot of that has to do with time. So let’s think together: How can we shave an hour or two off of these longer procedures without reducing quality. How can we do that? When the team is engaged — engagement means they’re thinking on their own without my direct influence — they’ll help create the solution, they’ll support the solution.

MD: Sure. And now she is responsible for her own raise. The doctor says, I want to give you a raise. I think you deserve one; you’re a fantastic employee, and here’s what we need to do in order to get to the point where we can do that. Or, if the staff is on some sort of bonus plan, certainly adding that extra fee on there — especially if the doctor is a financial arrangements person who doesn’t want to quote the $17,000 versus the $10,000. The doctor has got to feel a lot better about making bonus payments to the staff when they’re charging the right fee for these complex cases.

PH: And when you see it in black and white and you know it’s the right fee, now your leadership can take over. Establishing a fee for complex-care cases is a process. It’s not an emotional thing; it’s a process. When you have a process, you have the ability to lead because you can always go back to the tool. You can always go back to the fee analysis and say, OK, we’re doing better — now we just need to do a little bit better. You’re not just constantly raising the bar for the sake of raising the bar … because people get burned out on that. You cannot constantly ask people to perform better if they don’t have the right intrinsic reasons to do so. And the fee analysis provides that. It’s in black and white.

I would suggest visiting the Dental Practice Advisors website to get started. For the skills related to case acceptance, visit my website: paulhomoly.com. I can teach you and your team the essential philosophies and conversations that make it easy for your patients to say yes.

MD: That sounds like some great advice. I don’t know what the hardest job in the world is, but I can say that if every job in the world paid exactly the same, I’m not sure I’d still be a dentist. It is a difficult job. We’re working in a very sensitive area of people’s mouths and they tend to be afraid of us. It’s difficult and therefore we need to be compensated for it.

PH: Highly compensated!

MD: The only way to make sure that’s going to happen is to make sure your fees are in place. Whether it’s the 1-, 2-, 3-unit sweet spot crown fee that’s in place or the 12-unit case that you think is going to make you financially independent, in reality you’re going to make less money on that than on the 3-unit case unless you get your fees in order. So it’s something I would definitely encourage dentists to take seriously. Contact Ken for guidance on fees and to see if they are in fact in the right place. You don’t want to practice for 30 to 40 years and then find out you did everything right, except charge the right amount for procedures.

PH: Remember, Mike, you and I were going to have this fee conversation last year, at the beginning of 2009. And we both agreed: I don’t know if we should be talking about raising fees when the economy is tanking. So now, a lot of indicators say we’re coming out of that, and I hope the audience hears what I’m going to say right now. I’m not advocating that you go and raise your fees 40% to 70%. I’m not saying that. What I’m saying is, when the case is complex we need to think about taking our fees up. To make it easy for you: don’t take them up all at once. Maybe take that 6-unit case up 20%, just to build your confidence in quoting a higher fee, and keep bumping it. Don’t make the jump; don’t go cold turkey on this thing. Build your confidence with it. That way, when you begin to slowly escalate your fees for complex care, you will become more and more accustomed to quoting a higher fee.

MD: That’s one part of it, but the other part is making sure that the base single-unit crown fee for the 1-, 2-, 3-unit case is in the right place as well. And it might be! Or it might need to go up only $40 or $100. Or maybe it is in the right place, and then you just need to worry about more complex cases. But why not find out? Isn’t it kind of like getting blood work done? The good news is that you find out everything is fine and you don’t need anything. You don’t say: Well, that was a waste of time and money. Instead you say: Oh good, everything’s all right. Why not find out that your fees are in the right place now so you don’t have to worry about it 20 years from now, when things didn’t turn out the way you thought they would.

PH: And now you can pursue quality and be compensated at a level that will help perpetuate your practice and makes the pursuit of quality a sustainable event.

MD: Excellent. Well, thank you for stopping by today. I loved the opportunity to finally discuss fees with you, and I know that the readers and listeners of Chairside will love it as well.

For questions related to this interview or learn more about Dr. Paul Homoly, call 800-294-9370, visit paulhomoly.com or email paul@paulhomoly.com.