No-Prep Veneers: A New Ceramic Material That Makes Them a More Realistic Option

The ability to predictably bond thin pieces of tooth-colored restorative material to teeth and expect excellent long-term esthetic and functional results has created a new arena in the practice of dentistry — that of elective cosmetic treatment. This is not to say that these procedures “appeared overnight”; they did not. However, over the last 20 or so years, the materials and technologies have continued to improve. Now, many procedures in which longevity was felt to be compromised by the old-school critics have proven to be excellent and clinically viable treatment options. Teeth can now be “resurfaced” with tooth-colored restorative materials requiring very little, if any, tooth preparation.

Adhesive bonding technology allows the dentist to place a brittle restorative material of minimal thickness on the surface of the tooth that will not break under normal masticatory function. Consequently, patients who are not happy with the smile Mother Nature provided them can elect to have a “smile makeover” to correct esthetic problems associated with tooth shape, position and color. For many years, patients had to live with esthetic problems that were tooth related. Orthodontics could straighten teeth, but they could do nothing for malformation or problems associated with tooth color. The psychological ramifications to the patient of an unesthetic smile are only beginning to be understood and validated. Some dentists still believe that it is a “violation of the Hippocratic Oath” to disturb “healthy” tooth structure, even if the patient is unhappy with the esthetics; and that we should talk the patient out of elective treatment. In this day and age, such backward thinking is preposterous. For many patients, elective cosmetic dentistry can be a life-altering experience, giving those who weren’t lucky enough to be born with a “perfect” smile what they always wanted.

No-Prep Versus Minimal-Prep Porcelain Veneers

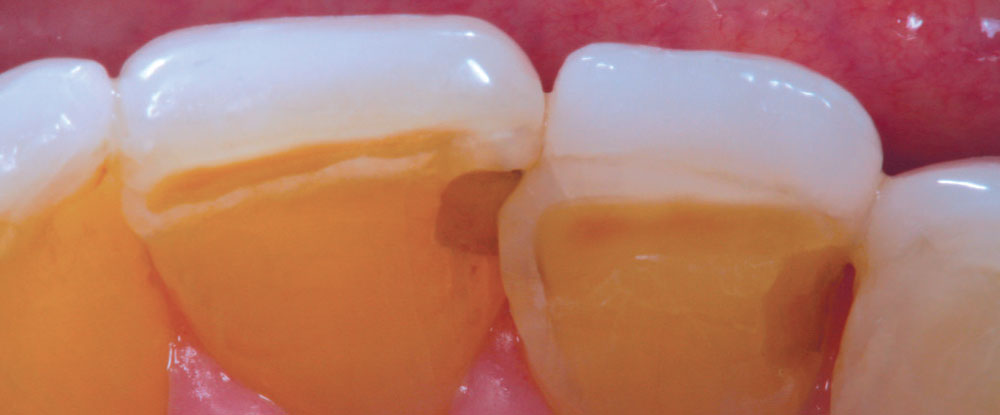

It has always been my belief that some preparation is required for porcelain veneer cases to achieve optimal esthetic and biologically functional outcomes. Crowded cases need not only the facial surface positions corrected, but the palatal surfaces as well (360-degree veneers) to functionally align these teeth and make home care and periodontal maintenance possible. Most of the restorations from no-prep cases that I have seen in my 27 years of practice have appeared to me as “unesthetic, opaque, monochromatic Chiclets” (Fig. 1). In many of these cases, the previous dentists have aligned the crowed facial surfaces only to leave the functional (palatal) surfaces uncorrected, making maintenance and restoration difficult, or even impossible (Fig. 2).

I believe the key to unlocking the major problems with the no-prep technique lies in selecting the proper case (small teeth with spaces, with slight lingual alignment being the most ideal), and having an all-ceramic material that is extremely thin and esthetic, yet strong. This also means that the cervical margins need to be extremely thin (knife edge), and be able to be finished by the dental laboratory technician. It is my opinion that it is nearly impossible to finish and polish ceramic margins in the mouth to the same degree as can be accomplished in the laboratory.1,2

The cervical margins need to be extremely thin (knife edge), and be able to be finished by the dental laboratory technician. It is my opinion that it is nearly impossible to finish and polish ceramic margins in the mouth to the same degree as can be accomplished in the laboratory.

Case Report: Performing “Family Esthetic Dentistry”

Case Planning and Making of Master Impressions

My youngest daughter, Christine, is in her early 20s. She had orthodontics in her early teens to correct minor tooth alignment issues. Since high school graduation, she has wanted porcelain veneers to make her teeth “bigger and brighter.” Personally, I have always felt that minimal-preparation porcelain veneers were the best option for long-term cosmetic changes for teeth. The enamel bond is very predictable, and esthetic changes can be made without the addition of added bulk to the tooth surface, particularly at the gingival margin where excessive emergence profile could have negative periodontal consequences. The strength and esthetics found at very minimal thicknesses of new materials like IPS e.max® (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, N.Y.) has caused me to rethink my opinion of no-prep veneers — especially if the margins can be precisely finished by the dental technician in the laboratory, allowing for minimal marginal refinement and polishing at the insertion appointment.

Figure 3 is a preoperative view of Christine’s smile. She has some minor surface hypocalcification secondary to orthodontic treatment, and some small incisal edge chips on both maxillary central incisors, as well as a minute diastema. An intraoral retracted view (Fig. 4) shows the corrected Class I occlusion with 2 mm of overbite and overjet. An occlusal/incisal preoperative view (Fig. 5) shows very flat labial surface profiles of the anterior teeth with adequately sized facial embrasure spaces.

It is important to have enough room in the facial embrasures to wrap porcelain around the proximal facial line angles while maintaining the soft triangular shape of the facial anatomic form. In order to have a smooth emergence angle of porcelain off of the unprepared labial surface, the gingival extent of the ceramic must begin in the intracrevicular area. This will allow the dental technician to finish the ceramic to a finely finished margin, thus limiting any potential overhang of the material. One of the problems with popular “no-prep” techniques, which often make the promises of “no shots” and “nonretracted” impressions, is that it is impossible to create an esthetic and biologically acceptable transition from tooth surface to porcelain that begins at the free gingival margin without creating an overhanging margin. Thus, many of these nonretracted, no-prep cases have the potential to result in gingival recession from bulky, overcontoured gingival margins (Fig. 6). Christine’s expectation was to have “bigger, brighter” teeth and her natural teeth were small. Fortunately, because she had flat labial surfaces with open facial embrasures, nature provided the “space” to allow the addition of porcelain without significantly increasing the overall thickness of the finished result.

The first step for any patient who is being considered for “no-prep” veneers is to make study models and have a laboratory wax-up done, to see if the addition of ceramic, without first creating the space, will result in a biologically and esthetically pleasing result.

The first step for any patient who is being considered for “no-prep” veneers is to make study models and have a laboratory wax-up done, to see if the addition of ceramic, without first creating the space, will result in a biologically and esthetically pleasing result (Fig. 7). Once the decision is made by the doctor and patient that an acceptable result can be achieved, an appointment for master impressions, interocclusal records and face-bow transfer can be made.

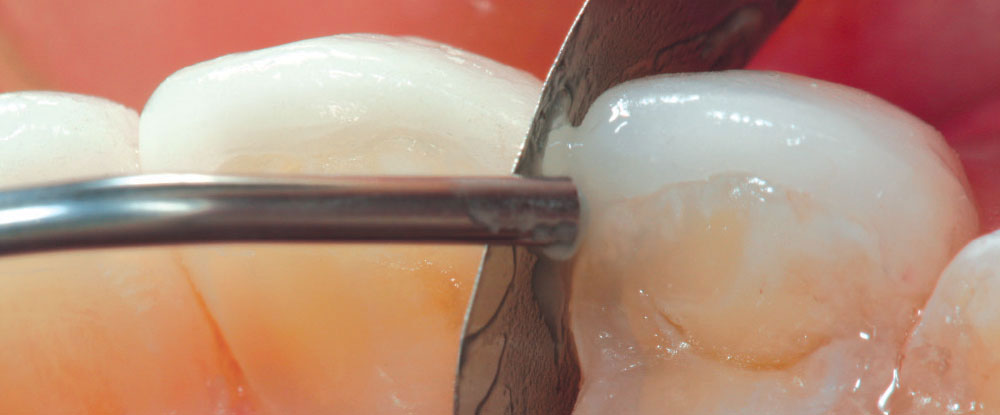

After administration of intrapapillary local anesthesia, a double-cord retraction technique utilizing a #00, followed by a #1 braided retraction cord (Ultrapak®; Ultradent; South Jordan, Utah), is used in preparation for making the master impression (Fig. 8). Upon removal of the top cord (#1) (Fig. 9), a space is opened up that will allow the light-bodied impression material to flow into the gingival crevice, accurately capturing an impression of the intracrevicular tooth surface. When the impression is poured in die stone (Fig. 10), the technician can now accurately construct the porcelain margins from an intracrevicular position and minimize any excessive contour of the restorative margin.

The Laboratory Perspective: IPS e.max® (Lithium Disilicate) — Thin, Strong and Esthetic!

— Contributed by Jeff Stubblefield, Dental Technician and Technical Director, DAL Signature Restorations, Peoria, Illinois

Dr. Lowe called me regarding the possibility of fabricating no-prep veneers for his daughter, Christine. I asked him to send me preoperative models and photos so that we could evaluate them together. We evaluated the casts using some specific criteria. First, the existing tooth length was evaluated to determine its optimum esthetic and functional position. Next, the alignment of the teeth was evaluated for spacing and/or rotation.

The preoperative casts were mounted on a Denar® Combi articulator (Whip Mix; Louisville, Ky.). An additive diagnostic wax-up was then fabricated idealizing the length-to-width ratio. This provides the dental laboratory technician with a guide for fabricating the veneers.

There are several materials that can be used to fabricate no-prep veneers. Traditional feldspathic porcelain is commonly chosen, but it can be brittle and difficult to fabricate in thicknesses of 0.3 mm to 0.5 mm. Cerinate porcelain — feldspathic porcelain reinforced with leucite crystals — can also can be used to fabricate these restorations. However, at DAL Signature Restorations (a Division of Dental Arts Lab), we use a product known as the “DAL Partial Prep Veneer” that utilizes the IPS e.max system. IPS e.max is a lithium disilicate ceramic displaying excellent strength with outstanding esthetics. It can be pressed easily into 0.3 mm to 0.5 mm thicknesses, providing a very accurate fit with precise restorative margins. By using the high translucency (HT) ingots, these restorations can blend into dentition to be practically “invisible.” From a materials strength perspective, IPS e.max pressed lithium disilicate exhibits strength measurements of up to 400 MPa. The porcelain system also has an entire layering system, which gives the dental ceramist the ability to provide outstanding esthetics. The DAL Partial Prep Veneer system is an evaluation-based system anchored in functional and esthetic design. Areas requiring slight or partial preparation are identified and communicated to the dentist.

To fabricate the no-prep veneers for Dr. Lowe, the master impression was poured up in die stone and indexed to create individual dies. The veneers were then waxed into an incisal matrix (Fig. 11) to ensure edge positioning. The wax-ups were then sprued, invested in a ring and pressed using IPS e.max HT BL2 ingots. After divesting and cutting the veneers off the sprues, they were custom cutback and layered using IPS e.max enamel layering ceramic. After contouring, the veneers (Fig. 12) were glazed and polished, then transferred to an uncut solid cast to ensure a passive group fit.3,4,5

Case Delivery

The completed IPS e.max porcelain veneers are shown on the master model in Figure 13.

The first step in the delivery process is to do a collective try-in to evaluate proximal fit and overall esthetics (Fig. 14). The anterior six restorations appeared to fit passively; however, the premolar restorations could not be fully seated when adjacent restorations were seated in place, which indicated that some proximal adjustment would be required. Figure 15 shows an incisal view of the ceramic restorations on teeth #8 and #9 and demonstrates the difference in facial contour and incisal edge position of the seated restorations as compared to the adjacent natural lateral incisors. It is clear that for most patients, a “no-prep” case will require all the teeth in the smile to be restored. Some clinicians have restored lingually positioned single teeth using the no-prep technique; however, to do this without creating overly thick incisal edges is a challenge in itself.

Once the try-in was completed and the restorations were approved by the patient, the bonding process was started. I prefer to start with the maxillary central incisors, moving distally, placing two teeth at a time to ensure proper fit. While some clinicians espouse placement of all of the restorations at once, it is my opinion that doing so can result in severe problems with delivery of the restorations to the proper positions on the teeth. Many times, the supposed “passive collective fit” does not guarantee that during the cementation process on the actual teeth, the fit will be entirely passive as well. Micromovement of the dies when fabricating the porcelain restorations can lead to a false sense of security regarding passive fit. Even a solid model does not guarantee that the collective fit on the patient will be accurate. It is not uncommon to have to do minor adjustments on the proximal surfaces of the cemented restorations to allow the next restorations to fit correctly, even though they appeared to have a passive fit at try-in.

Moving on to the maxillary premolar region, some difficulties were encountered during the seating process.

After etching of the maxillary central incisors with 37% phosphoric acid (Pulpdent Corporation; Watertown, Mass.) for 15 seconds, the teeth were rinsed for a total of 15 seconds, then thoroughly air-dried. The fifth-generation bonding agent DenTASTIC™ UNO™ (Pulpdent) was painted on the etched surface with a microbrush, air-thinned and light-cured per the manufacturer’s instructions. The veneer cement Kleer-Veneer™ (Pulpdent) was placed on the inner surface of the veneer and then placed on the tooth (Fig. 16). The excess cement was then removed using a sable artist’s brush prior to tacking the restoration with the curing light (Fig. 17). Kleer-Veneer light-cured veneer cement is ideally suited for extra thin no-prep veneers because it has absolutely no color and will not influence the final shade of the restoration. Also, with a 9 µm film thickness, an accurate fit is assured. Because the maxillary anterior teeth were relatively flat anatomically, the corresponding restorations were placed with only minimal proximal adjustment.

Moving on to the maxillary premolar region, some difficulties were encountered during the seating process. Again, although these restorations appeared to have a collective passive fit on the laboratory models and at try-in, it did not work out that way at the delivery appointment. One of the problems that arose as we progressed posteriorly was that the facial embrasures were smaller, which made it more difficult to wrap the porcelain on the adjacent restorations into the proximal areas. It was also difficult to create a knife-edge ceramic margin, thus causing an imprecise fit of the restoration in that area (Fig. 18). To correct the fit of the restoration on tooth #12 at placement, a dead-soft matrix band was placed in the interproximal area on the mesial aspect. After etching with 37% phosphoric acid, rinsing, placement and curing of adhesive resin, the small area was filled using a flowable composite resin (Fig. 19). The area was then finished and polished with composite finishing burs, discs and rubber abrasive points. It is important to realize that this procedure is not “patching” an incompetent margin; there is no margin on the tooth surface for a no-prep veneer restoration. The small area is merely “sealed” with composite bonded to enamel to create a smoother proximal transition to the restoration of tooth structure. The next time, opening these embrasures slightly with a diamond bur (prior to the master impression) would solve the problem.

Another “embrasure issue” was encountered when attempting to deliver the restoration for tooth #4 (Fig. 20). The small size of the facial embrasure did not allow the restoration to fully seat on the mesial aspect. To correct the problem, the distal surface of the cemented restoration was lightly adjusted in the contact area with a composite finishing diamond (ET3; Brasseler USA; Savannah, Ga.) (Fig. 21). Once the premolar restoration seated passively, the adjusted area on the distal of the seated restoration was polished with porcelain polishing abrasives (Brasseler USA) prior to placement of tooth #4 (Fig. 22).

After all the ceramic restorations were delivered, the marginal areas were painted with a surface sealant (Seal-n-Shine™; Pulpdent) to seal any microscopic imperfections that may have existed (Fig. 23). Because Seal-n-Shine’s “Embrace Technology” is reported by the manufacturer to be “moisture forgiving,” the material was brushed on all facial and palatal margins of the restorations, even intracrevicular margins, as well as available interproximal margins, air-thinned, then light-cured (Fig. 24). Finally, the occlusion was checked with AccuFilm® II (Parkell; Edgewood, N.Y.) and any discrepancies were identified and polished. Figure 25 and Figure 26 show the postoperative full-smile and full-face views of Christine’s completed smile. She loved it so much she said, “Dad, when can we do the lowers?” I said, “Christine, we will try tooth whitening first!”

My First No-Prep Veneer Case: A Retrospective

I have always been skeptical about any procedure or product that makes claims that are too good to be true. A bigger problem is created when a credible procedure or product tries to be “everything for everybody,” rather than just sticking to what it does best. Marketing hype leads patients to believe that no-prep veneers are for everyone! No shots, no loss of precious tooth enamel, no painful impressions; we can even line them up in a tray, squirt in the cement and place them all at one time! In my opinion, this same hype leads dentists to believe that no-prep cases are easier to impress and deliver than the prepared alternatives.

After completing hundreds of prepared cases and only one no-prep case, it is my opinion that these “easy no-prep cases” are much harder to deliver successfully. The advantage of even a minimally prepared case is that there is a definite marginal seat and no overall dimensional change. The best no-prep cases are those where nature has made the space already, such as diastema closure cases, microdontia (peg laterals) or excessive wear cases. All of these have been “prepared” in some fashion; just not by a bur. Patients who have normal width-to-length ratios, facial contours, crowded teeth or facially positioned teeth (filled buccal corridor) would not, in my opinion, be good no-prep candidates. Also, the ceramics that are most common with no-prep veneers are very thin, leucite-reinforced and highly opaque, making the accomplishment of a high degree of texture and esthetics very difficult, if not impossible, for the dental laboratory technician to achieve. IPS e.max lithium disilicate is a highly esthetic and extremely strong ceramic. Proper case selection and using this ceramic material shines a whole new light on the possibilities for the no-prep veneer case. In my mind, it was the perfect solution for my daughter’s case, and I treat all patients as if they were family!

Dr. Robert Lowe is in private practice in Charlotte, North Carolina. He lectures internationally and publishes on esthetic and restorative dentistry. Contact him at boblowedds@aol.com or 704-364-4711.

References

- ^Strassler HE. Minimally invasive porcelain veneers: indications for a conservative esthetic dentistry treatment modality. Gen Dent. 2007 Nov;55(7):686-94.

- ^Malcmacher L. No-preparation porcelain veneers – back to the future. Dent Today. 2005 Mar;24(3):86, 88, 90-1.

- ^Etman MK, Woolford MJ. Three-year clinical evaluation of ceramic crown systems: a preliminary study. J Prosthet Dent. 2010 Feb;103(2):80-90.

- ^Guess PC, Strub JR, Steinhart N, et al. All-ceramic partial coverage restorations – midterm results of a five-year prospective clinical splitmouth study. J Dent. 2009 Aug;37(8):627-37.

- ^Wolfart S, Eschbach S, Scherrer S, Kern M. Clinical outcome of three-unit lithium disilicate glass-ceramic fixed dental prostheses: up to 8 years results. Dent Mater. 2009 Sep;25(9):e63-71.