The Hidden Sources of Temporomandibular Disease

“All who drink of this treatment recover in a short time, except those whom it does not help, who all die. It is obvious, therefore, that it fails only in incurable cases.” – Galen (129 C.E.-199 C.E.)

“If we do not know what causes a malrelationship, we will probably fail in our treatment.” – Peter Dawson (1989)

Introduction

Temporomandibular disease (TMD) is a problem for dentists.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Since its discovery, dentists have diligently sought out a cause and cure, while well-meaning clinicians and scientists proposed widely variable, often conflicting, hypotheses as to its etiology, diagnosis and treatment.5,7 The quest is a cure for those who suffer, but varying results for patients indicate the prize remains elusive.7

Since the early 1900s, TMD research has been plagued by design problems, misuse of research data (both negative and positive), poor controls, flawed conclusions based on inadequate sample sizes, inconsistent results, hucksterism and therapeutic gimmicks as questionable as they are fashionable. Further complicating progress is the unfortunate division between antagonistic camps of clinicians, each boasting “gurus” of varying competence who proselytize a favorite theory or fad treatment, while sniping at competitors over ramparts of self-righteous piety.1,4,5,7

The result of this confusion is that, regardless of treatment, some patients improve, others get worse and some remain the same. How are we to help our patients? How can we be healers when what we know or learn is inconsistent with a universal “cure”? It seems that no matter the camp to which you belong — no matter which diagnostic technique, theory or treatment is tried — patient results vary. It is by fortune only that most patients, regardless of the treatment (or lack thereof), improve.5,7

It seems that no matter the camp to which you belong – no matter which diagnostic technique, theory or treatment is tried – patient results vary. It is by fortune only that most patients, regardless of the treatment (or lack thereof), improve.

TMD Causes and Treatments

TMD is a complex disease or set of diseases (syndrome).1,2,3,4,5,6,7 The most consistent symptom is pain about the face, with complaints focusing on the TMJ (joint), teeth, muscles of mastication, and skin covering the face and jaws. This discomfort can be severe, intermittent or episodic, and is found in certain groups (e.g., young to middle-aged women) more than others (e.g., men).5

Sources for TMD are far-ranging. A non-exhaustive list of diagnosed causes to date include misalignment of the TMJ disk (e.g., displacement), occlusal disharmony, muscular incoordination, poor temporomandibular function, hyperactive muscles (e.g., bruxing), deviated tooth inclines, excessive axial pressure, misshapen condylar or fossa anatomy, fatigued muscles, vitamin deficiency, unfriendly environment, stress, hormonal irregularities, differing centric occlusion/relation, improper canine rise, “evil” spirits, inadequate vertical dimension, open bite, insufficient freeway space, impinged neutral zone, excessive tooth wear, dislocation, fracture, tendonitis, myospasm, arthrosis, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, infection, metabolic irregularities, ankylosis, fibrosis, developmental disorders (congenital), neoplasms, recent trauma, past trauma, psychological factors and sinus infections.1,2,3,4,5,6,7

TMD has supposedly been cured (or “successfully treated”), in some cases, by addressing one or several of the causes with which it happens to be currently associated. Unfortunately, the efficacy of addressing these causes is a hit-or-miss operation. Generally, when the pain stops, a cure is announced.7 But in well-designed, large patient studies, there is seldom any correlation except time.5,6,7 Whether it is due to the actual treatment, unidentified psychological factors (e.g., catharsis over multiple visits), patient boredom, the passage of time, the cost or a combination of all of these, the longer the patient is treated, the greater the chance of a reduction of symptoms as expressed by the patient. Admittedly, some cases are very clearly caused by recognizable pathology (e.g., TMJ arthritis, neoplasms, gross occlusal disharmony), but most exhibit inexact or diffuse symptoms (which differing camps emphasize more than others) and respond modestly to treatment, if at all. Therefore, there must be more factors influencing the causes of TMD than what we dentists traditionally expect.1,2,3,6,7

Generally, when the pain stops, a cure is announced. But in well-designed, large patient studies, there is seldom any correlation except time. Whether it is due to the actual treatment, unidentified psychological factors, patient boredom, the passage of time, the cost or a combination of all of these, the longer the patient is treated, the greater the chance of a reduction of symptoms as expressed by the patient.

Dentists are trained for dental and perifacial care. We examine and treat the teeth, mouth and surrounding structures — including the TMJ — and seldom look beyond. This is not due to incompetence, but rather to disadvantages stemming from ultra-specialization, training and legal limitations. Below are some areas that significantly impact TMD, but are considered “off-limits” by traditional dental society and thus ignored by most dentists — even very good dentists. They do not include all the sources for TMD, but a mere few in a vast arena of symptoms, causes and treatments. I call these the “Hidden Sources of TMD.”

Neurologic

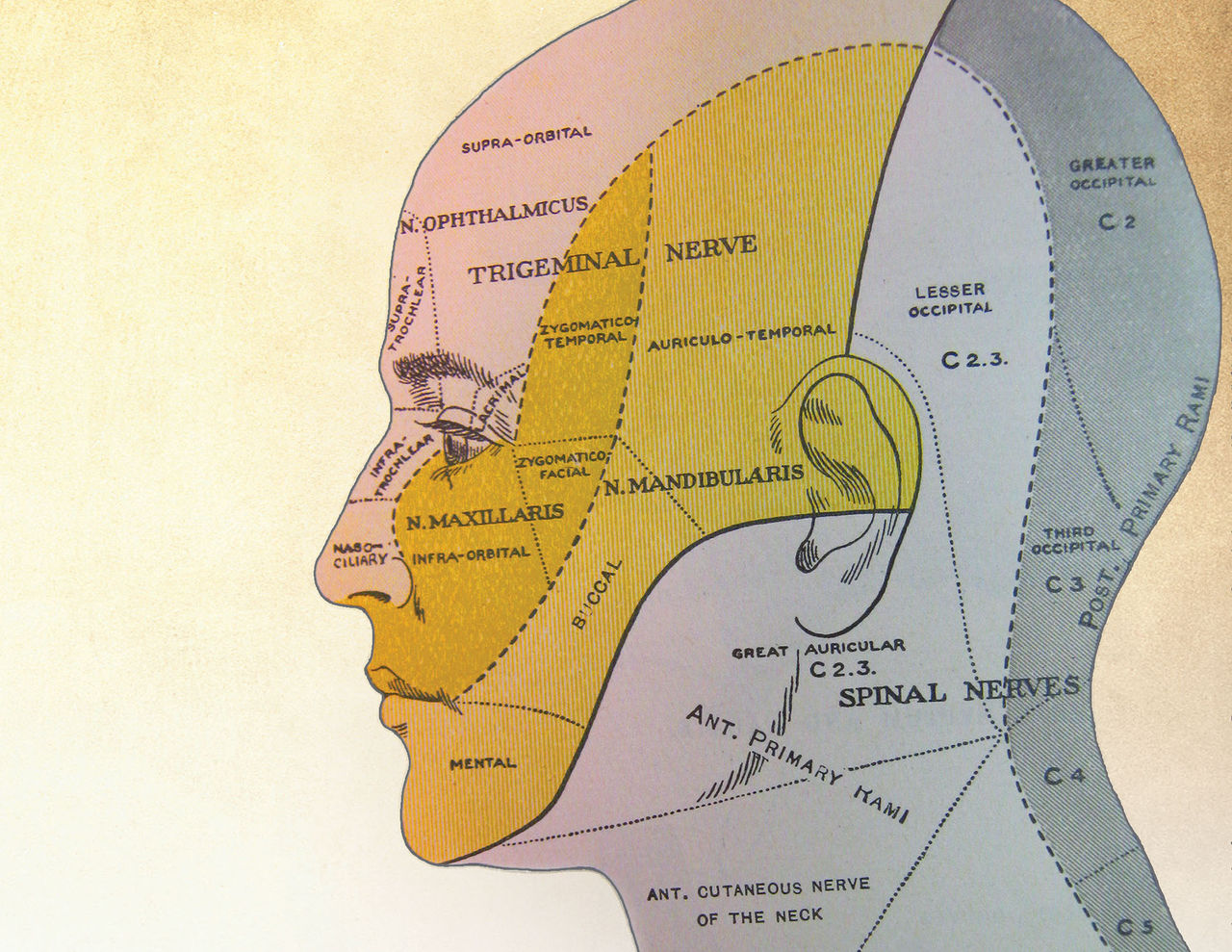

As dentists, we all took neuro in our first year of dental school. We identified the nerves, neural nets, neuro-physiology and anatomy of the head (and perhaps the rest of the body). We were taught that nerves “innervate” specific areas. For instance, the trigeminal nerve (V) has three divisions with cutaneous sensory distribution to: 1) the ophthalmic branch, which covers the forehead, eye and top of the nose; 2) the maxillary branch, which covers the skin behind the eye, lower nose, cheek and upper lip; and 3) the mandibular branch, covering the temple, side of the face, TMJ region, anterior ear and most of the mandible. C2 and C3 of the great auricular nerve (cervical plexus) cover the back of the head, angle of the mandible, neck, ear, etc. (Fig. 1).1,2,3,4,5,6,7

To dentists, selected and trained for their obsessiveness (who else in the world worries about a 50 micron margin?), these limits are often taught as (and thus considered to be) exact limits, as expressed on neural maps.2,4,5 Unfortunately, these maps are all wrong.6 The innervation maps are approximate, and plagued by high rates of anatomic variations and overlaps (the extension of innervation beyond the prescribed boundary of the maps).4 For example, in dental school, the innervation maps show the mandibular nerves stopping at the midline of the chin. Once we got into practice, however, we quickly learned that in most cases of mandibular block anesthesia, the numbness did not stop at the midline exactly, but often extended beyond that mark by a centimeter or two.2 This reflects the reality that the mandibular nerve does not, in fact, always stop at the midline: it has overlap. For some people it does; for others, it does not.

Other nerves behave in a similar way. The innervation of C2-C3, for instance, is only a few millimeters from the TMJ; therefore, in a TMD evaluation, you must worry about more than just the mandibular branch of V because it is very likely that C2-C3 will also innervate part of the TMJ and surrounding anatomy.2 Yet in all our TMD studies, this overlap is seldom considered, and most dentists do not evaluate this neural source of pathology (in fact, few dentists are even able to perform the basic neurological head exam).5,7 In addition, there is substantial nerve overlap of the TMJ by the acoustic nerve (VIII), the accessory nerve (XI) (sternomastoid), the hypoglossal nerve (XII), and their respective branches.4,6 Some patients will have greater overlap than others, which may explain why everyone with a similarly diagnosed TMD syndrome is not equally helped by the standard treatment.5,7

The innervation of C2-C3, for instance, is only a few millimeters from the TMJ; therefore, in a TMD evaluation, you must worry about more than just the mandibular branch of V because it is very likely that C2-C3 will also innervate part of the TMJ and surrounding anatomy.

Facial pain, and the psychological fallout it evokes, can also influence the TMJ, the muscles of mastication and the local cutaneous areas, contributing to (or exacerbating) TMD. Conditions possibly leading to facial pain include: tension headache, cluster headache, migraine, posttraumatic headache, depression, neuralgias (trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, migrainous, postherpetic), neoplasms, cranial arteritis, benign intracranial hypertension, subdural hematoma, sinus infection, cardiovascular disease, spasmodic torticollis (XI) and atypical facial pain of unknown etiology (15% of all headaches).1 In addition, myofacial pain, stemming from muscle pathology, can result from cervical myalgia and occipital neuralgia, and postherpetic neuralgias can seriously scar the ganglia, producing pain and TMD symptoms.1,7

All of these conditions, seldom mentioned in TMD-related dental literature, can and do influence patients with TMD symptoms. In a study of 1,600-plus facial pain patients, 35% had tension headaches, 23% had migraines, 15% had headaches of unknown etiology, 3% had neoplasms, and 2% had migrainous neuralgia, with the remainder mixed in variety (e.g., cluster headaches, etc.).6 How many TMD patients are among these patients? No one knows, for few researchers can or have tried to separate and isolate TMD pain from cases of generalized facial pain. To complicate the issue, between 50% and 60% of the population complain of at least one of the previously mentioned facial pain symptoms at any particular time.2,5

Vascular

Vascular pathology, such as trauma and temporal artery disease, can also refer pain to the TMJ area, thus creating TMD symptoms.6 The facial artery, internal maxillary artery, sphenopalatine artery, deep and posterior auricular arteries, and inferior alveolar artery are in close association with the blood and nerve supply of the TMJ complex.2 Any pathology in these vessels can result in TMD symptoms, either by direct nerve compression or by referred pain. Temporal (giant cell) arteritis, an inflammation and swelling of the walls of cranial arteries, is well-known to cause headaches, jaw pain and “chewing” pain (i.e., jaw claudication), due to the close positioning of the vessels and nerves encased in small bony channels in the skull (depending on individual anatomy). When the artery wall swells, ischemia, ion transport interruptions and traumatic crushing of the nearby nerves produce damage, resulting in most uncomfortable sensations.6

Otic (Ear)

The ear is a very delicate organ. A slight problem can cause unbelievable misery (e.g., vertigo), essentially incapacitating an otherwise healthy person. Much of the ear, with its many blood vessels and nerves, is encased in a hard bony matrix, providing no room for swelling, yet still containing some openings for exogenous invaders to exploit and cause havoc. As the ears are only millimeters away from the TMJ, the potential exists for this anatomy, as well as anatomic variations like overlap of nerves and blood supply, to cause TMD symptoms.4,6

Problems with the ear’s numerous blood vessels, including the anterior and superior tympanic artery, tubal artery, caroticotympanic artery, mastoid artery, subarcuate artery and deep auricular artery, can cause direct or referred pain to the TMJ area. In particular, the superficial petrosal artery and stylomastoid artery lay anatomically next to the facial nerve, and supply it with blood. So, too, the internal carotid artery, which often occludes with plaques, lies only 0.5 cm from the facial nerve. Any defect in these vessels will result in a serious impact on the TMJ sensorium.4,5,6,7

The nervous system of the ear area is also intimately associated with the efferent and afferent fibers of the facial nerve (VII), through close proximity and overlap. Remember, if one part hurts, everything can hurt, especially when it comes to the facial nerve. Otic innervation includes the vestibulofacial anastomosis and vestibular nerves, the petrosal nerves (greater superficial and deep), vidian nerve and chorda tympani. Problems with these nerves (e.g., inflammation), as well as those caused by a pathologic acoustic nerve (VIII), can trigger a TMD symptom response.2,3

The ear also has spaces and canals, which can become pathologic and trigger TMD symptoms. The eustachian tube can get blocked (e.g., filled with water), or the ear may develop acute or chronic otitis, myringitis and perforations, causing edema and nerve compression due to vascular engorgement. Labyrinthitis, osteitis, spontaneous drainage (with diabetics), trauma and obstructed venous, and lateral and petrosal (superior and inferior) sinuses are all potential TMD trouble areas.2,3,4,5

It is interesting that so many problems with the TMJ can be linked to ear pathology, yet few dentists even own an otoscope, let alone look at the ear canal or sniff it for purulent drainage smells. Remember, 4% of the general population has otitis media (and probably TMD symptoms) at any one time. In the U.S., that is approximately 12.4 million people today.4,6 As a firsthand example, in my practice alone, fully one-third of new “TMD” patients examined have bloody ear canals (otitis media).

Drugs

In our society, most of the adult population takes therapeutic drugs. The older they are, the more medications they take. Of the top 10 most dispensed drugs in 2007 (hydrocodone/APAP, lisinopril, atorvastatin, amoxicillin, levothyroxine, hydrochlorothiazide, azithromycin, atenolol, simvastatin, alprazolam, furosemide, metformin), eight include side effects of head and facial pain.8 Only hydrocodone/APAP and amoxicillin are generally free of muscle pain symptoms. This implies that alprazolam, a benzodiazepine tranquilizer (30% headache side reaction); metformin, an antidiabetic drug (19% headache side reaction); and many other medications can cause serious TMD symptoms, apart from any anatomic or pathological cause.2,3,8

To illustrate this point, I once had a patient with TMJ pain who was taking the ACE inhibitor lisinopril (5 mg daily) for high blood pressure. When he stopped taking the drug, the TMJ pain stopped; when he resumed the drug, the pain returned. After several more weeks of taking the drug, the body acclimated to the new pharmacological reality, and the pain stopped. This is very common with ACE inhibitors. If he had received any of the TMD treatments during this time (e.g., splint, full coverage, surgery), it would have appeared as if a cure was effected. In reality, this was a TMD problem caused by the drug’s side reaction. Now imagine a frazzled housewife with three bratty kids, drinking five cups of coffee a day (caffeine), smoking half a pack of cigarettes (nicotine), taking lisinopril for hypertension, Synthroid® (Abbott Laboratories; North Chicago, Ill.), Prozac® (Eli Lilly and Company; Indianapolis, Ind.), birth control pills, Lunesta® (Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.; Marlborough, Mass.) and the tranquilizer Valium (“when necessary”), all of which have headache as a side reaction.

It is interesting that so many problems with the TMJ can be linked to ear pathology, yet few dentists even own an otoscope, let alone look at the ear canal or sniff it for purulent drainage smells. Remember, 4% of the general population has otitis media at any one time.

I have never seen a TMJ/TMD study that considers the drugs the patients are taking as a confounding variable.5,6,7 This one fact nullifies most TMD therapeutic research. Drugs such as Prozac, Lunesta, benzodiazepines, oral contraceptives (migraine) and so forth can cause or exacerbate TMD symptoms.4, Not only do 80% of the most commonly prescribed drugs have head/muscle pain as a side reaction, but many of the psychoactive drugs taken by patients in groups with high occurrences of TMD also have head and muscular pain as additional side reactions. Given these facts, one must realize that drugs can cause or negatively influence TMD symptoms. As dentists, we should be aware of what drugs cause TMD and ask our patients if they are taking any of them.

I once had a patient with TMJ pain who was taking the ACE inhibitor lisinopril (5 mg daily) for high blood pressure. When he stopped taking the drug, the TMJ pain stopped; when he resumed the drug, the pain returned. After several more weeks of taking the drug, the body acclimated to the new pharmacological reality, and the pain stopped.

Psychological

Psychological problems involving the perception of pain and muscle mobility (e.g., clenching, bruxism) are another well-known, major factor in head pain and TMD … and are grist for another five articles or so.

Conclusion

So where do we go from here? With all of the relatively unknown potential causes of TMD mentioned in this article, can the dentist be of any help? The answer, of course, is yes! We must perform better examinations, considering not only the standards such as occlusion, disk position and muscle function, but also the previously mentioned conditions as well. Get an otoscope and look in the ears. Sniff for otitis media. Check and modify the patient’s drug lists. Do not rely on only one technique or theory to diagnose or treat. Look outside the mouth, too. Go from the simple treatments to the more complex. Consult the patient’s physicians about drug modification. Reassure your patients. Help them relax. Do what works for you and your patients. Do no harm. Time, psychology and healing are on our side. Good luck!

Acknowledgment

The author would like to give special thanks to neurologist Stephen Northrop, DDS, M.D.

Dr. Ellis Neiburger is a general practitioner in Waukegan, Illinois. Contact him at 847-244-0292 or eneiburger@comcast.net.

References

- ^Brass LM, Stys PK. Handbook of neurological lists. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1991.

- ^Lindsay KW, Bone I, Fuller G. Neurology and neurosurgery illustrated. 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1992.

- ^Miller JQ, Fountain NB. Neurology recall. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

- ^Spillane JA. Bickerstaff’s neurological examination in clinical practice. 6th ed. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Science; 1996.

- ^Dawson PE. Evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of occlusal problems. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1989.

- ^Perkin GD. Mosby’s color atlas and text of neurology. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998.

- ^Greene CS, Laskin DM. Long-term evaluation of treatment for myofascial pain-dysfunction syndrome: a comparative analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983 Aug;107(2):235-8.

- ^Wynn RL. Top 50 prescription medications dispensed in pharmacies in 2007. Gen Dent. 2008 Nov-Dec;56(7):604-7.

*Copyright 2010 by E. Neiburger*