In Praise of Electric Handpieces

Dental technologies, techniques and materials allow us to achieve results that were considered unachievable just several years ago. The public’s appreciation for dentistry and its presence in the media is at an all-time high. Whereas dentists used to be associated with pain, held in fear and regarded as “drillers, fillers and billers,” today they are recognized not only as healers, but as artists. We have come a long way!

Dental manufacturers have provided the profession with “smart” technologies, making the daily delivery of dentistry much easier and more efficient. Auto-mix materials, advances in adhesives, and computer and imaging technologies have revolutionized the profession. However, there has been little change to the piece of dental equipment that patients fear most: the “drill.” The handpiece is the most frequently used tool in the dental office, as it performs intraorally for tooth preparation and oral surgery, as well as extraorally for polishing and adjustments. Over the past several years, the use of electric handpieces in North America has been growing, and various manufacturers offer electric units.

Dental manufacturers have provided the profession with “smart” technologies, making the daily delivery of dentistry much easier and more efficient

Although marked as a “new” technology, the use of electric handpieces is not new at all, as they have been used worldwide for many years. Dentists in many countries have long practiced in small single-room operatories in older buildings where air lines cannot be brought from a central compressor to a dental unit have been dependent on electrically powered units.

Electric handpiece technology sits somewhere between the conventional air-driven high- and low-speed, as it generates up to 200,000 rpm of rotation, which is far less than the 400,000-plus rpm of air-driven units. However, they are far more efficient, as they have more than three times the cutting power (60 W vs. less than 20 W).

The electric handpiece will not slow down, stall or stop when the bur is applied to tooth structure or restorative materials. It cuts continually with constant torque. Electric handpieces also provide a greater concentricity of the rotating bur during tooth preparation, causing less “wobble” than air-driven units. This creates more precise margins, less heat buildup and less bur chatter, resulting in a more defined and cleaner cut. They also don’t create the high-pitched whining sound that makes patients cringe in fear, which is a huge psychological bonus.

In my operatories, both high-speed and slow-speed tasks have been assumed by electric motors. In fact, we use two units to eliminate the need for changing handpiece heads and settings (Fig. 1). However, one handpiece and controls can easily serve as both a high-speed and low-speed. The electric handpiece has become an indispensable tool for crown preparation.

Crown Preparation

We begin our initial reduction using a Great White Ultra carbide #856-018 (SS White Burs; Lakewood, N.J.) in order to reduce 1.5 to 2 mm from the occlusal surface of the tooth (Fig. 2).

This makes the subsequent axial reduction easier, as there is less surface area to reduce. Depth cuts are then placed (Figs. 3, 4) and are joined (Fig. 5), creating a consistent axial reduction of 1 mm. The Great White burs are large and cut very efficiently due to their dentated form. Conventional diamond instruments clog during bulk reduction in crown preparation, as their diamond particles clog with debris from the cut tooth and restorative material. Ninety percent of the crown preparation is accomplished with this one carbide. For the final finish, we switch to a KUT 3139 Coarse diamond (Dental Film Club; Montreal, Canada) (Fig. 6) to refine the axial walls and a KUT 3833 Coarse diamond (Dental Film Club) to shape the occlusal surface (Fig. 7). We then complete the final preparation, switching to fine diamonds and polishers.

Electric handpieces … provide a greater concentricity of the rotating bur during tooth preparation, causing less “wobble” than air-driven units.

- Removing old porcelain to metal crowns

Many of our daily dental procedures involve removing older crowns that need replacement. Air-driven handpieces are very inefficient for this task, as the porcelain and underlying metal of the crowns are difficult to cut, which creates heat and causes the bur to stall. These procedures are very hard on the air turbines, causing them to wear prematurely and necessitating expensive replacement. Electric handpieces make removal of existing crowns a snap. We first create a groove in the porcelain using a KUT 2135 Coarse diamond (Dental Film Club) (Fig. 8), which is ideal for grooving porcelain and zirconium. Once the underlying metal is exposed, we permeate it with a #557 carbide (SS White Burs) (Fig. 9), and pry the crown off with an EB134 hand instrument (Brasseler USA; Savannah, Ga.) (Fig. 10). This procedure becomes fast and efficient with an electric handpiece.

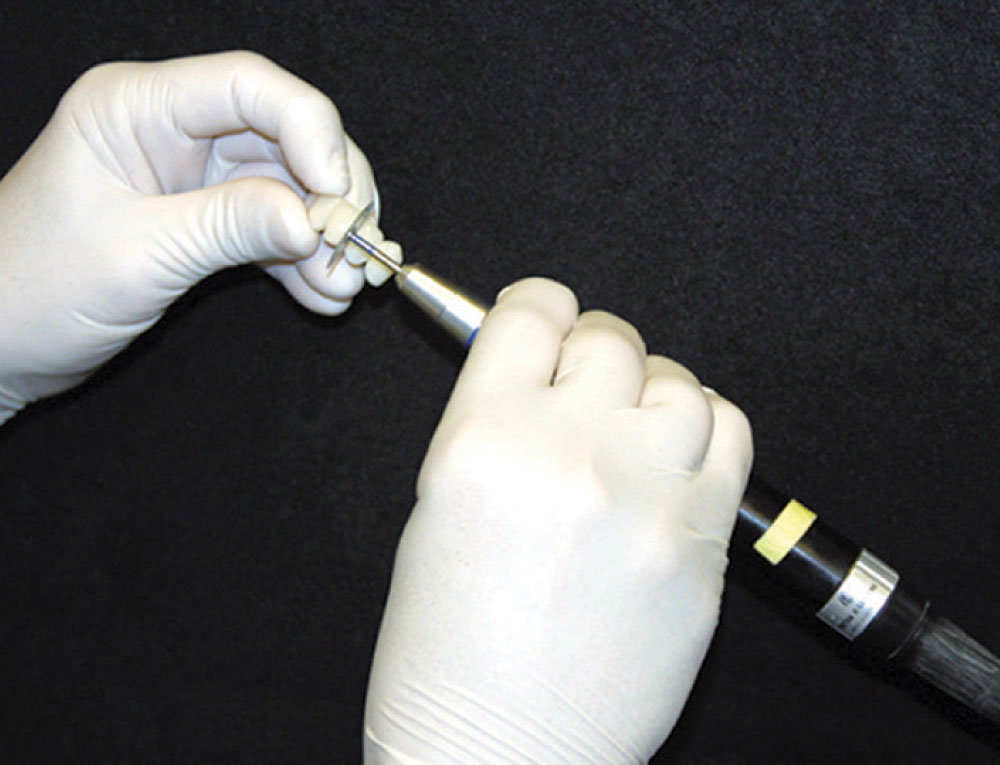

- Use as a slow-speed

I used to continuously fight and be frustrated by my air-driven slowspeed. It would stall, making shaping and adjusting acrylic and metal very aggravating.

Electric handpieces never stop. Problem resolved (Fig. 11).

New technologies and techniques serve to make the practice of dentistry better, faster and easier. Although electric handpieces may be considered to be expensive by some dentists, their benefits in time and efficiency are well worth the investment.

Electric handpieces make removal of existing crowns a snap.

Dr. Elliot Mechanic practices esthetic dentistry in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He is Oral Health’s editorial board member for esthetics.

Reprinted with permission of Oral Health Journal, Copyright © July 2009, Oral Health Journal.