Community Service: Giving Back with an Obsidian Smile Makeover

INTRODUCTION

The young woman in this case had fallen under some very tough personal circumstances and needed dental help. Community service takes many forms, and in our office, we give back by taking on huge reconstructive cases.

CASE DESCRIPTION

The patient presented with a large edentulous space in the anterior maxilla, severe vertical ridge atrophy and pronounced retrognathia. Due to the patient’s lack of vertical clearance, implants, bridges and partial dentures were contraindicated as treatment options. Instead, a fixed prosthodontic solution was chosen.

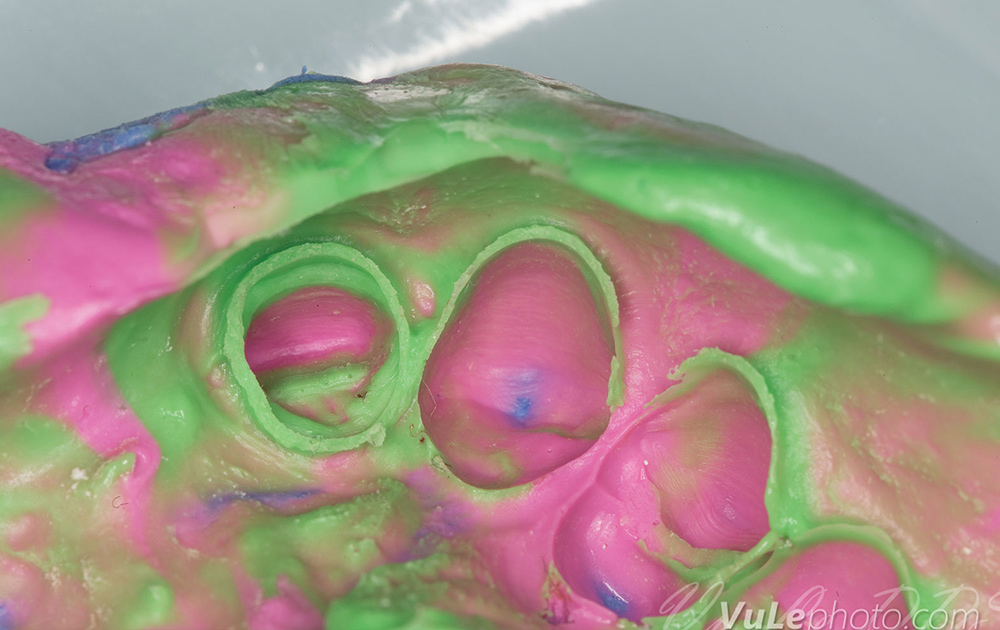

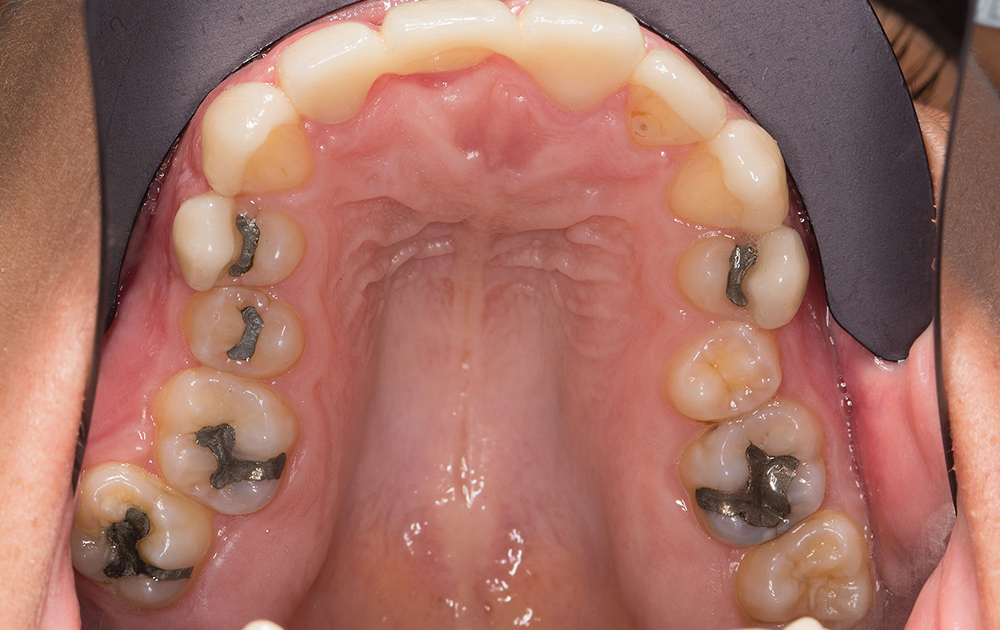

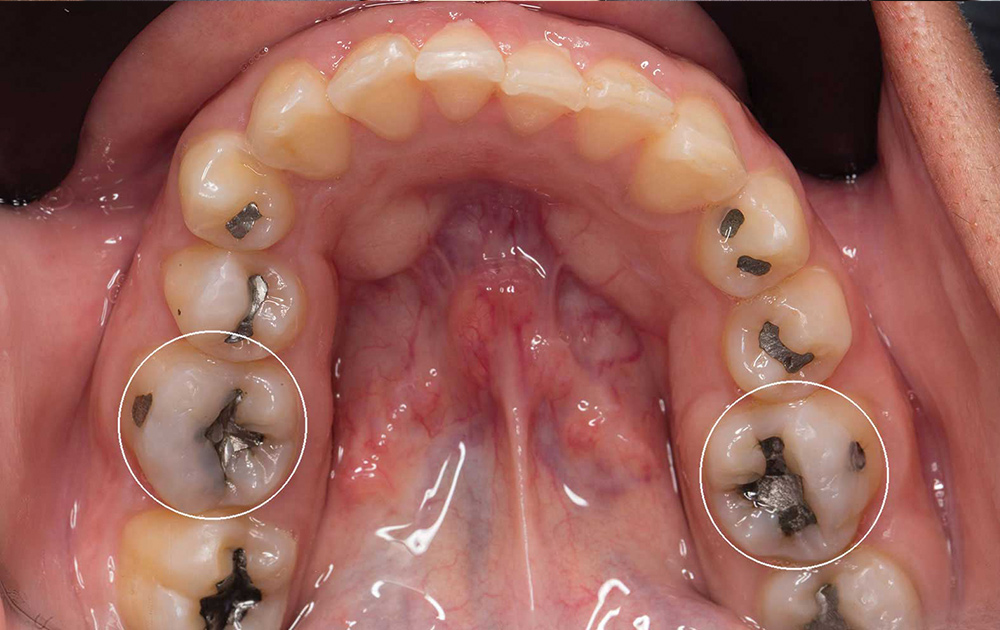

After using intraoral photography to communicate shade and translucency for the final restorations to the dental laboratory, chairside temporaries were made using a putty mold of the lab’s diagnostic wax-up. Porcelain fused to metal, Obsidian® lithium silicate ceramic (Glidewell Laboratories; Newport Beach, Calif.) and BruxZir® Solid Zirconia (Glidewell Laboratories) restorations were then fabricated at the lab. While the patient accepted all three restorative materials, Obsidian ceramic — a monolithic material that both exceeds the strength requirements for cemented all-ceramic restorations and can be bonded when desired — was selected for its combination of esthetics and high flexural strength.

The photo essay that follows details the restorative procedures used in this multiple-unit case to provide the patient with a successful smile makeover.

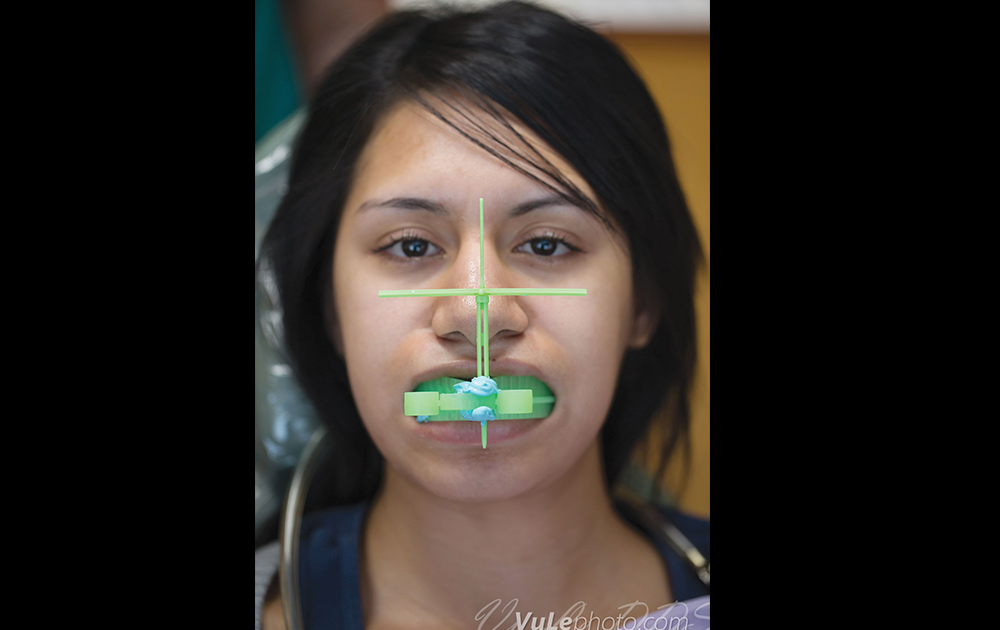

CONSISTENT INTRAORAL PHOTOGRAPHY

Accurate photography is as important to color communication as a clear impression is to the restorative fit. My recipe for reliable intraoral images is using a digital SLR (DSLR) camera that allows you to dial in the image. The settings on my Canon EOS 6D are: manual mode, ISO 200, f/22, 1/160 sec. or faster shutter, and white balance set to the flash preset. Or, you can leave the flash on automatic. Add flash compensation of +1/3 or +1/2 if the images are consistently too dim. If you consistently dial these settings into your camera, you will be rewarded with consistent results.

To ensure I get all the settings right every time, I have programmed a preset into my camera. Most mid-level DSLRs feature a custom preset mode, usually labeled C1 and/or C2. After the initial headache of programming all these settings, you can turn on the flash, spin the dial to C1 and now the camera is ready to shoot. If I mess something up, I click the mode dial off of C1, then back to C1 again to reset the camera to its memorized, foolproof dental settings.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Few patients have the knowledge, circumstances and resources necessary to achieve functional or esthetic perfection. It is our job as clinicians to deliver the best possible set of compromises that fits within the patient’s needs, wants and means. For this multiple-unit case, an Obsidian makeover provided the patient with a successful restorative result. Sometimes we are faced with problems far in excess of the funds available to solve them, but when the opportunity comes to give back to the community, don’t be afraid to dream big. The rewards from cases like these far outweigh the costs.

Dr. Vu Le has a general dentistry practice in Foothill Ranch, California, with a strong emphasis on technology and photography. For examples of his work, visit his office website, simpletooth.com, or his photography website, vulephoto.com. Contact him at 949-600-7777, vuledds@simpletooth.com, or on Twitter (@theSimpleTooth) or Facebook.

Disclosure: The author has no ownership or financial stake in any dental vendor or lab, including Glidewell Laboratories. Lab fees were waived in this case. No monetary compensation was received for the photography, written content or professional services performed.