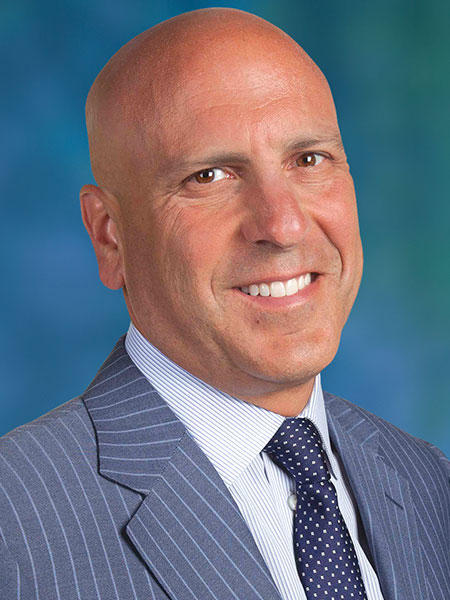

Photo Essay: Utilizing Limited Orthodontics in a No-Prep Veneer Case

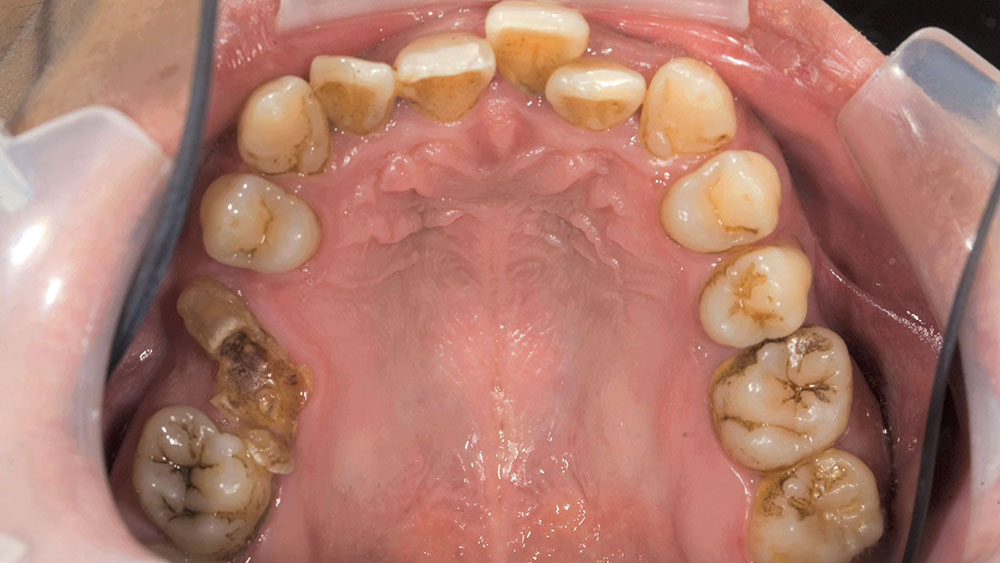

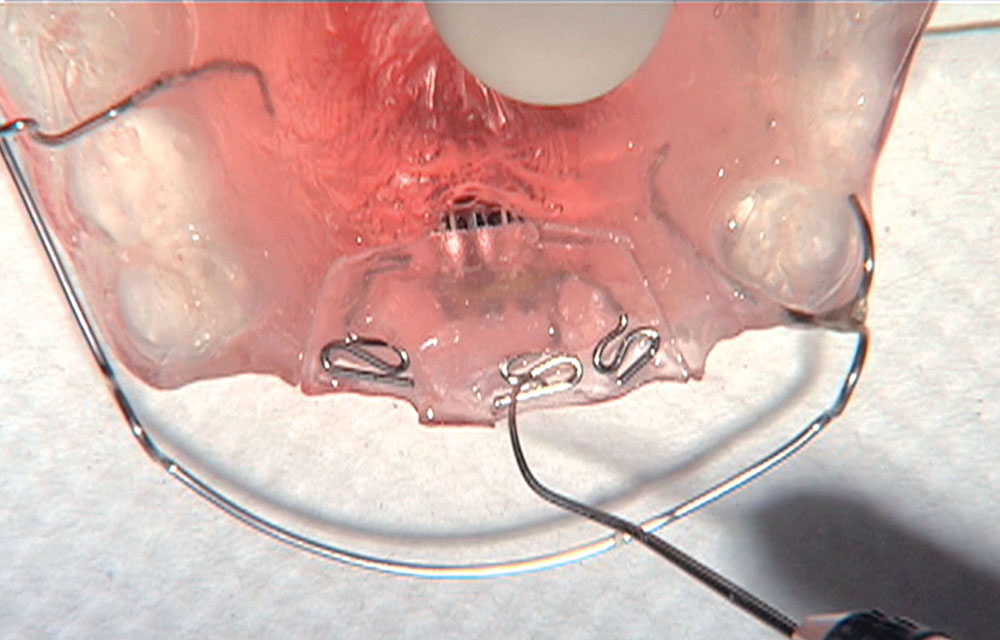

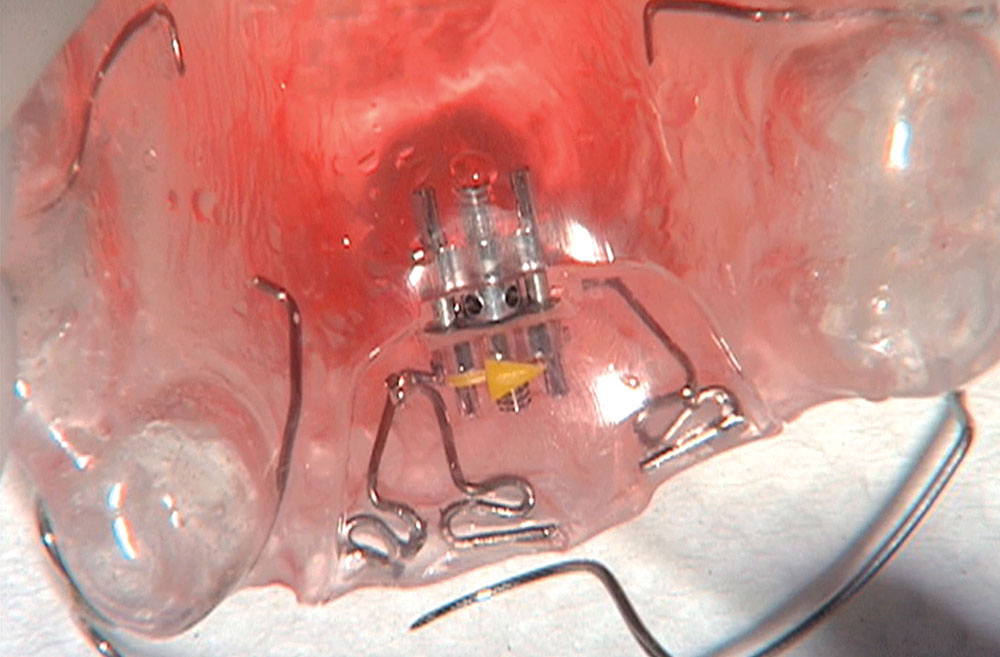

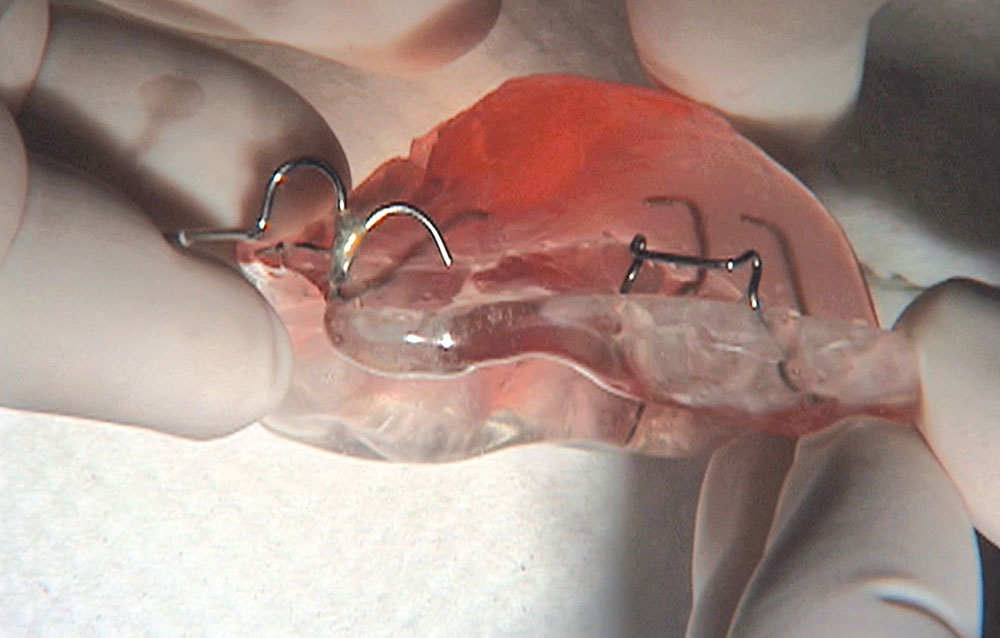

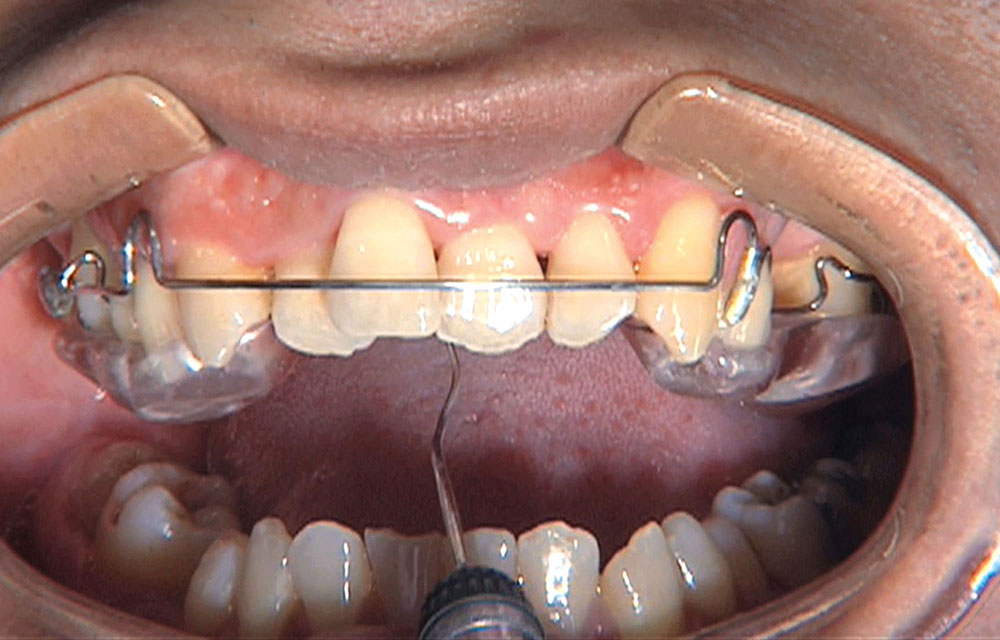

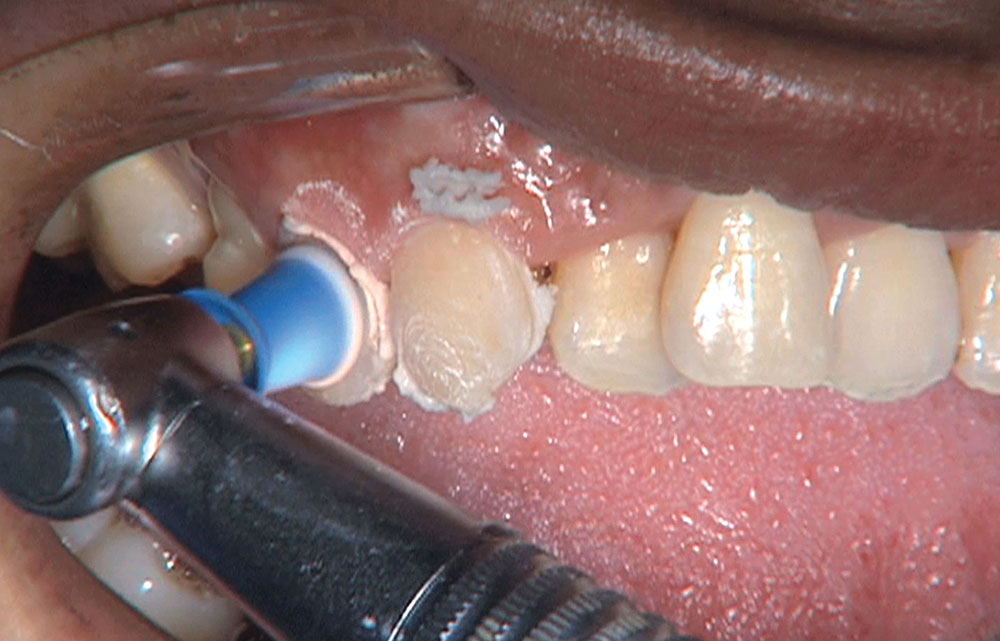

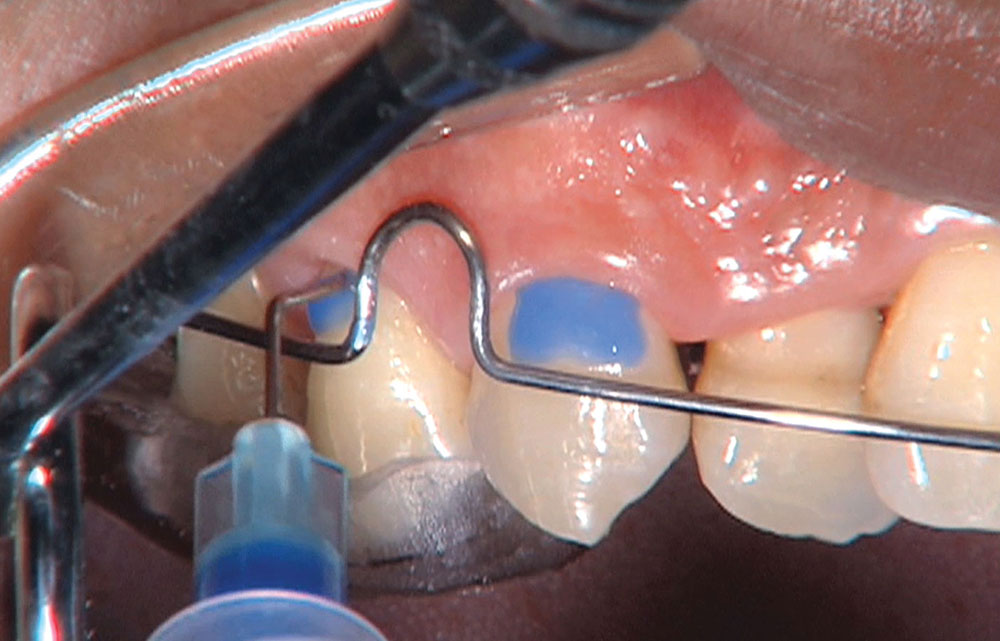

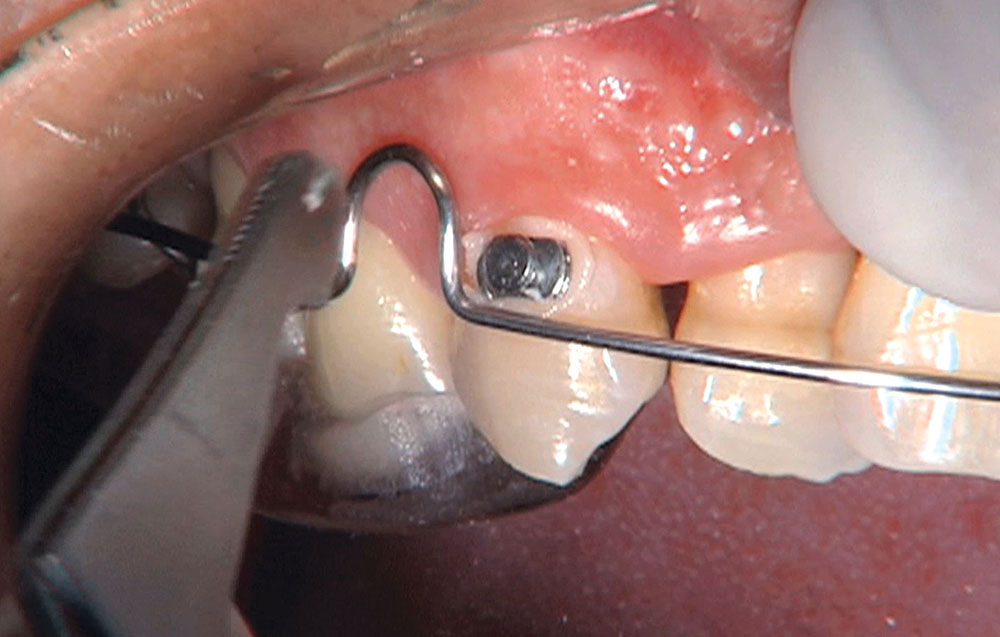

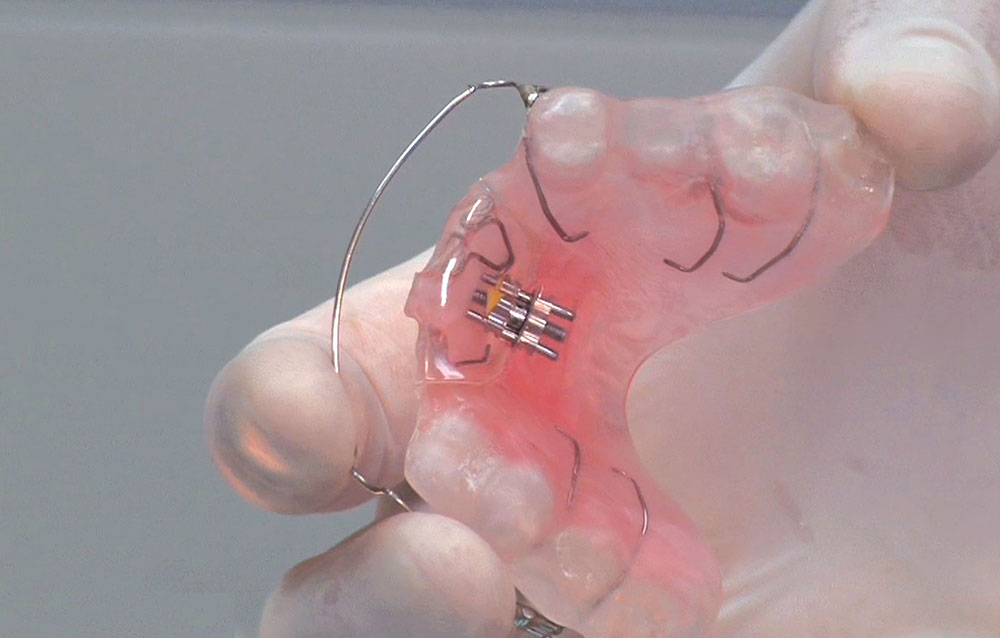

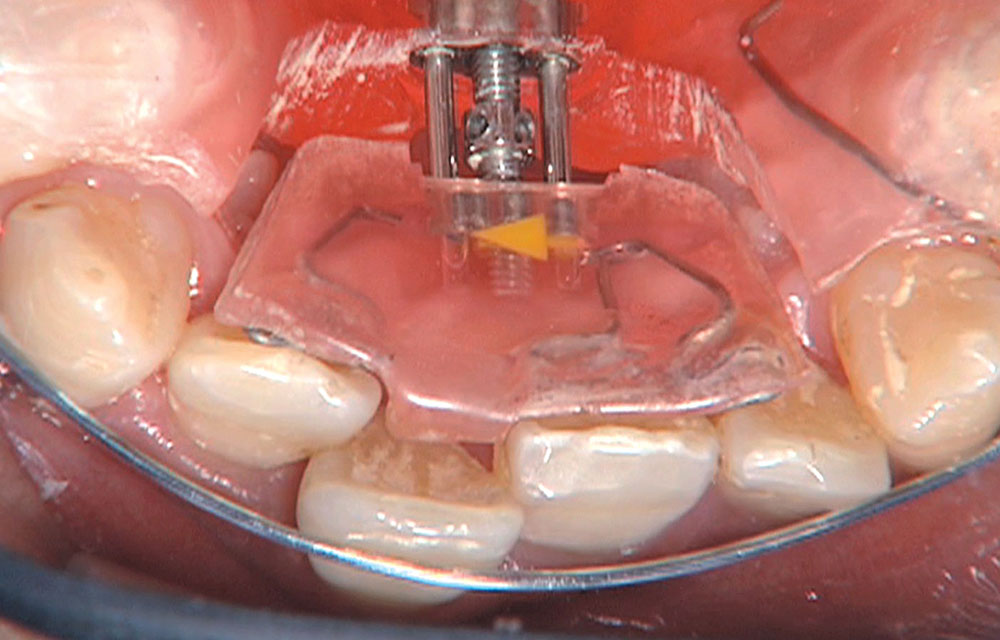

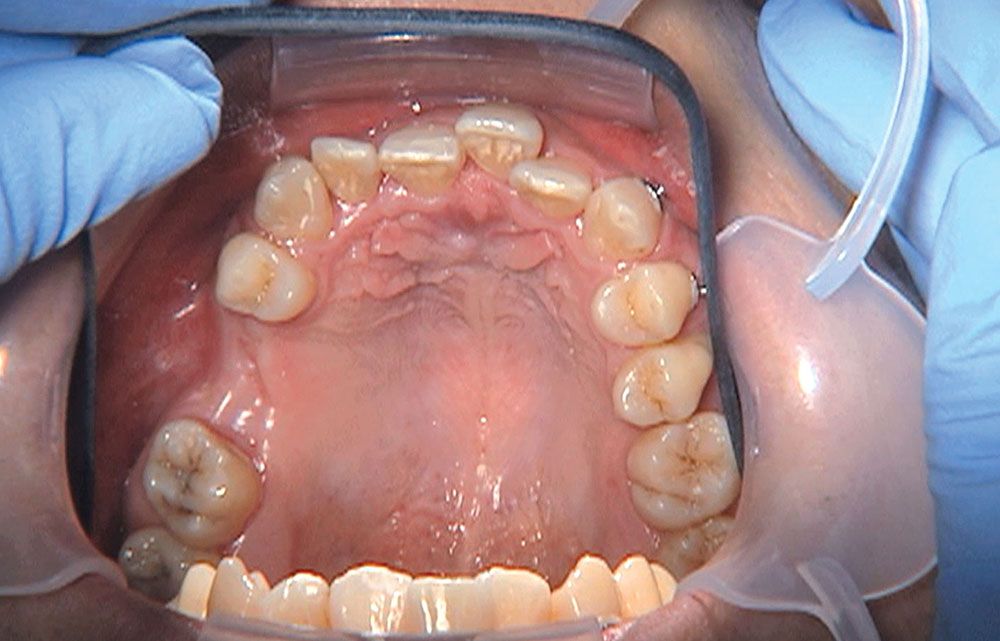

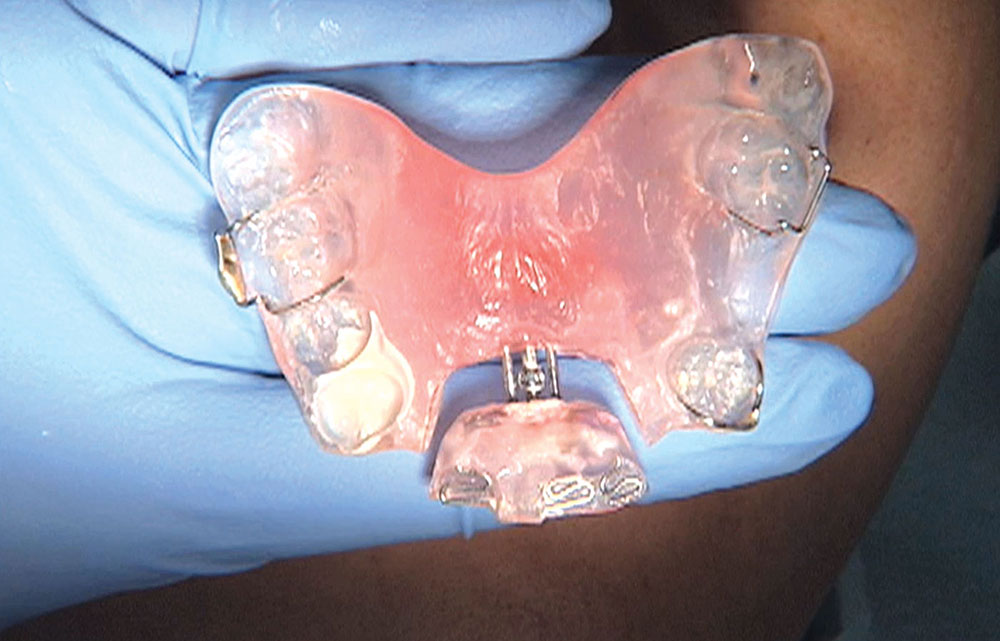

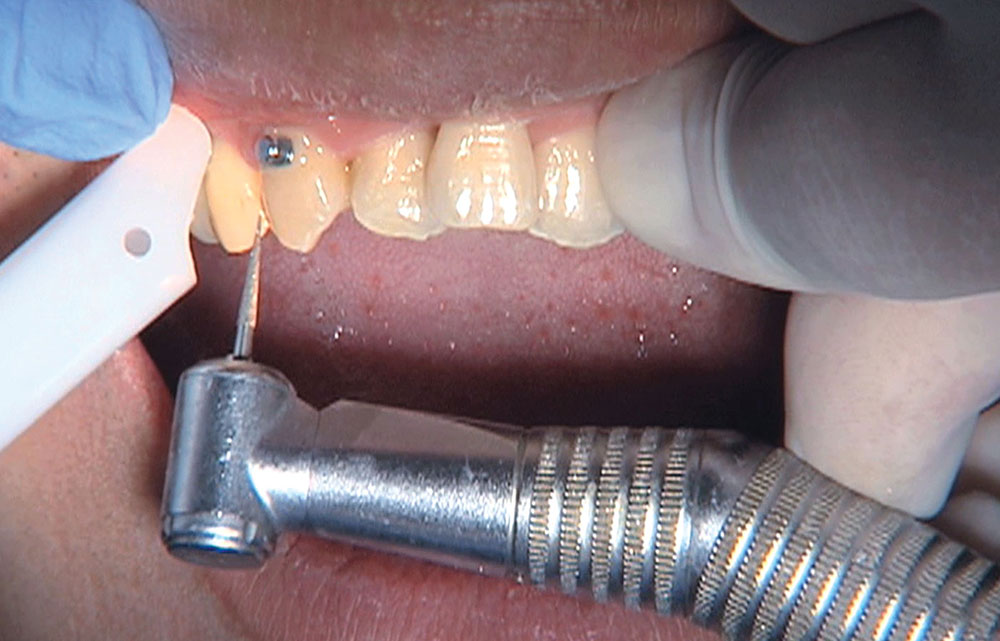

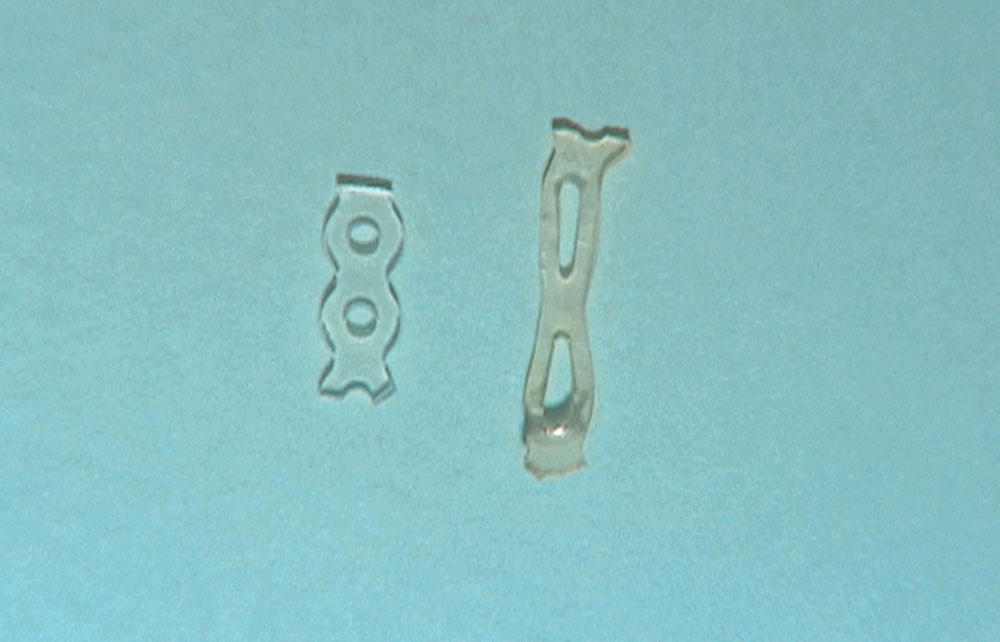

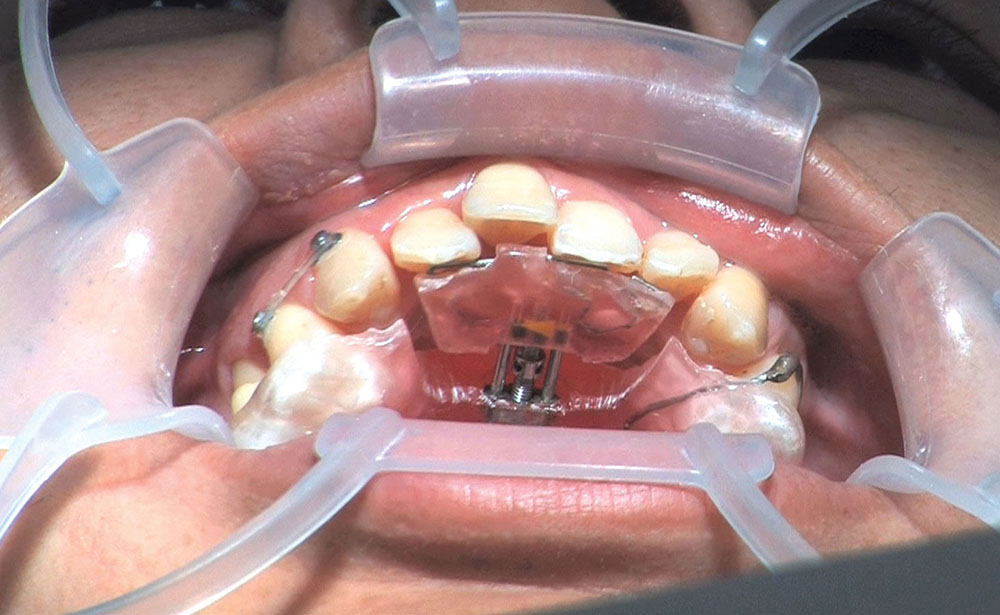

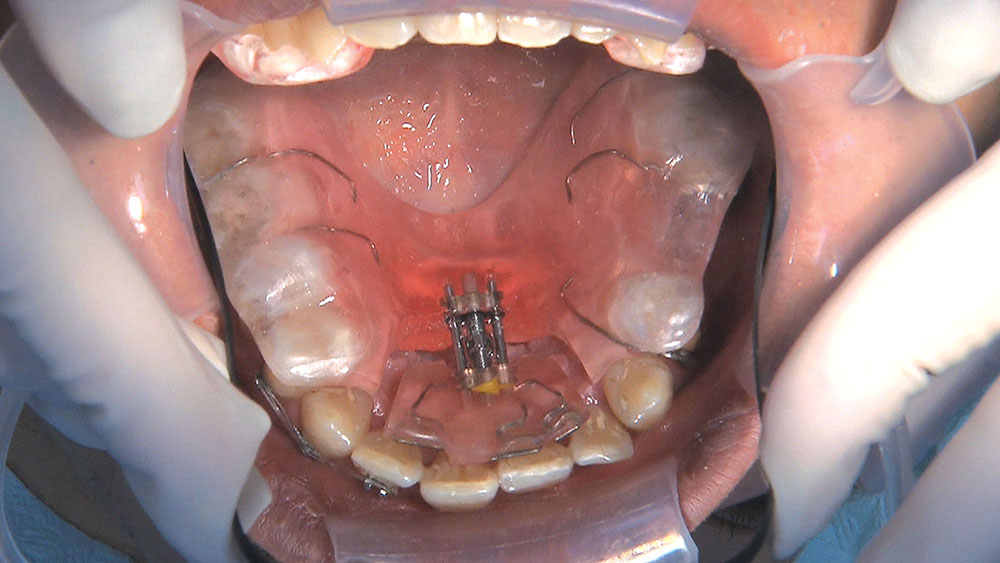

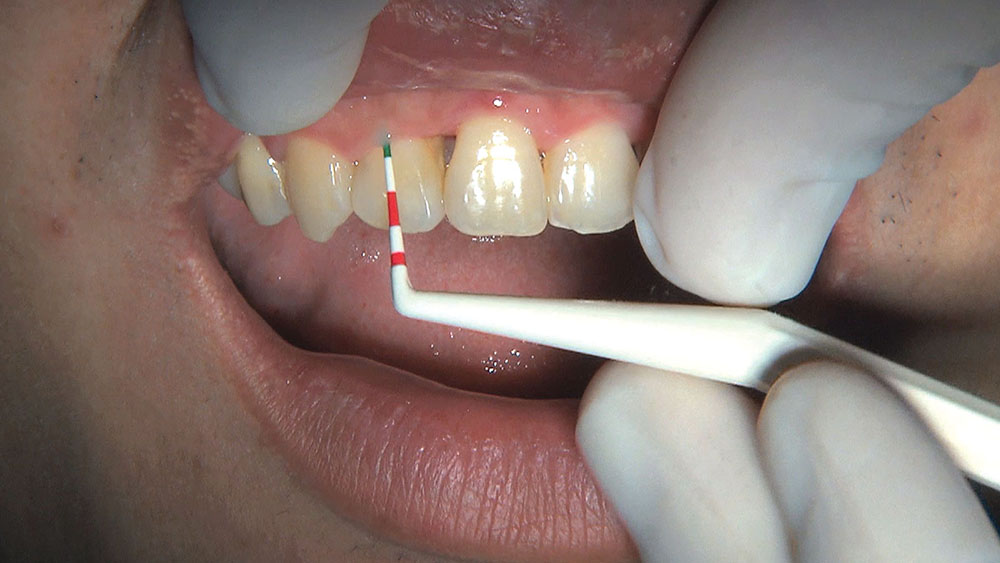

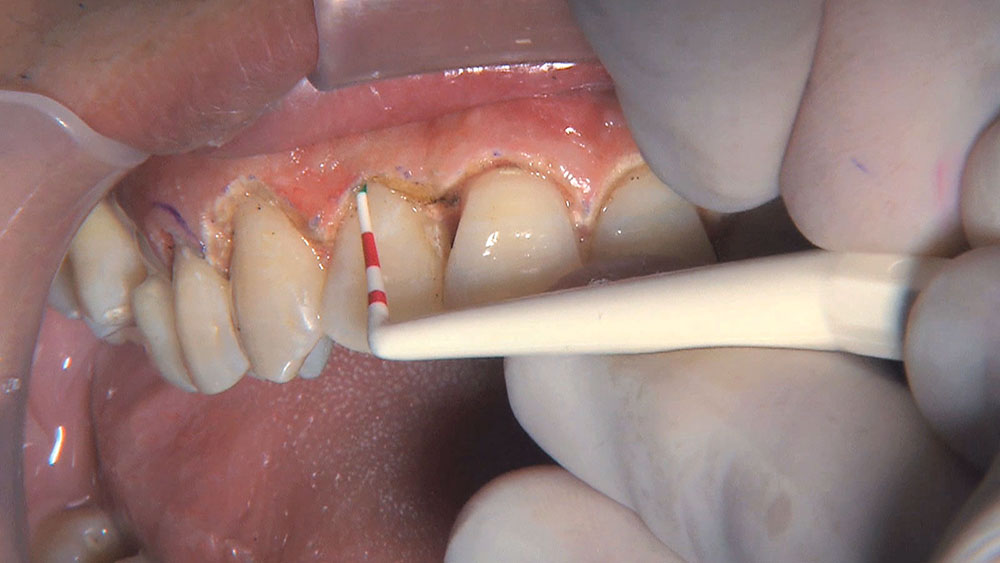

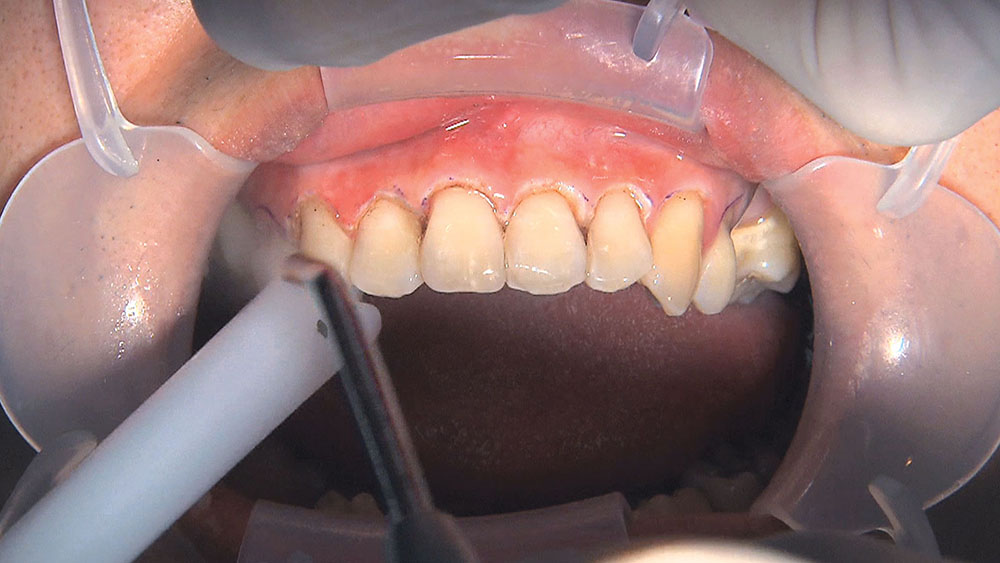

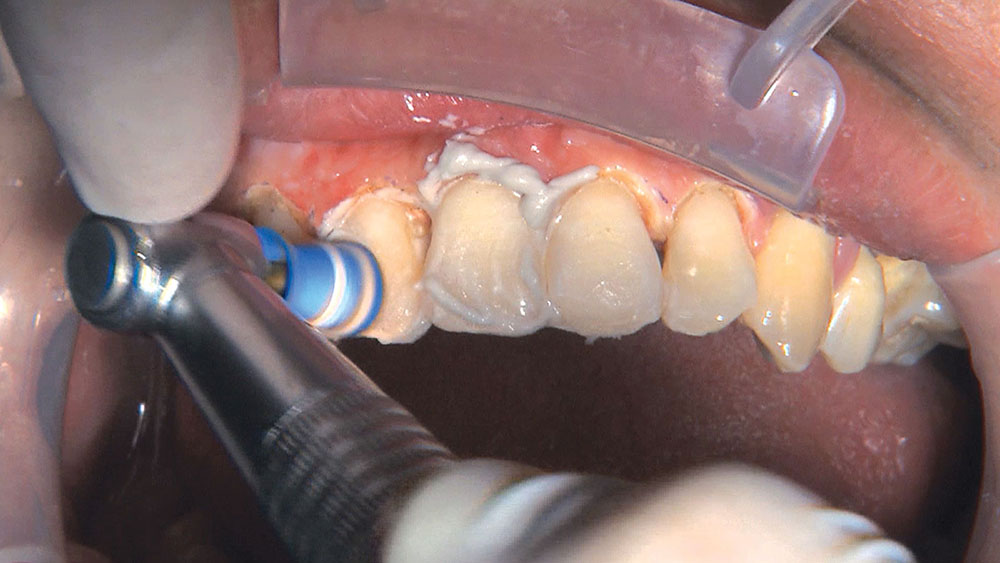

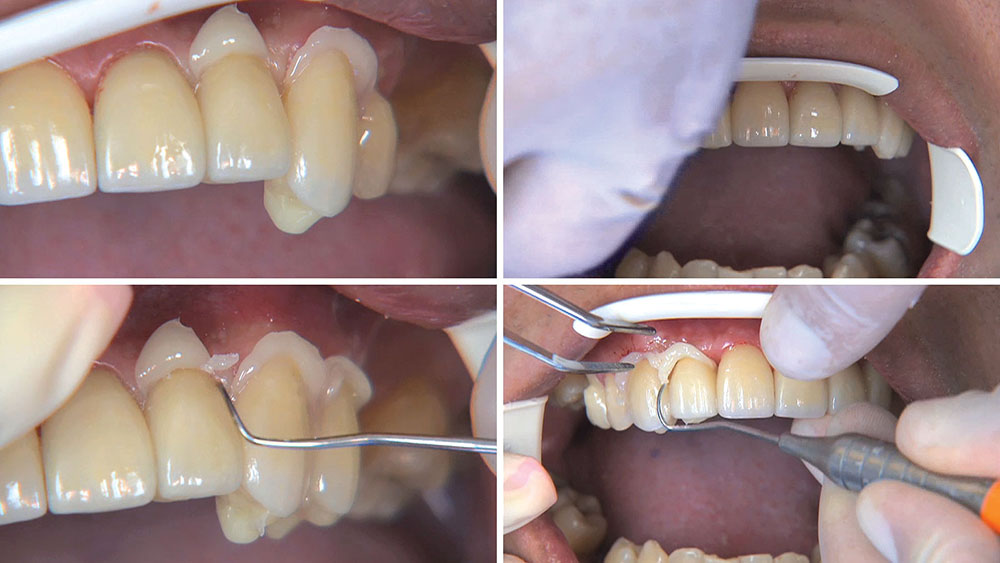

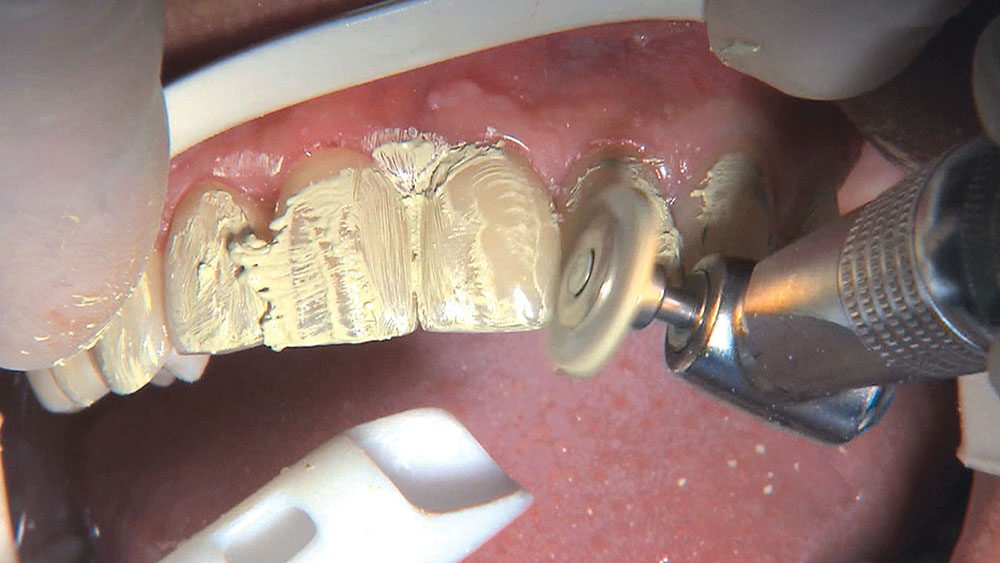

When this patient came in wanting to improve his smile, it was clear this wasn’t going to be a straightforward veneer case. I used to do orthodontics in my practice, and I’m comfortable using removable appliances to correct clinical conditions such as crossbites, so I had Space Maintainers Laboratory fabricate a removable appliance for me. I could have used a fixed appliance with either an anterior or posterior bite plane to correct the crossbites, but the patient convinced me he would wear the removable appliance as instructed. These types of cases take a while to reach completion, especially when the patient tells you that fixed orthodontics (brackets and archwires) are off the table. You could always refer the ortho portion of the case to a specialist, but most of the dentists that I speak with enjoy the process of minor tooth movement, whether it is with an appliance like the one I use in this case, or a series of clear aligners.