Clinical Technique: Diagnostic Wax-Ups

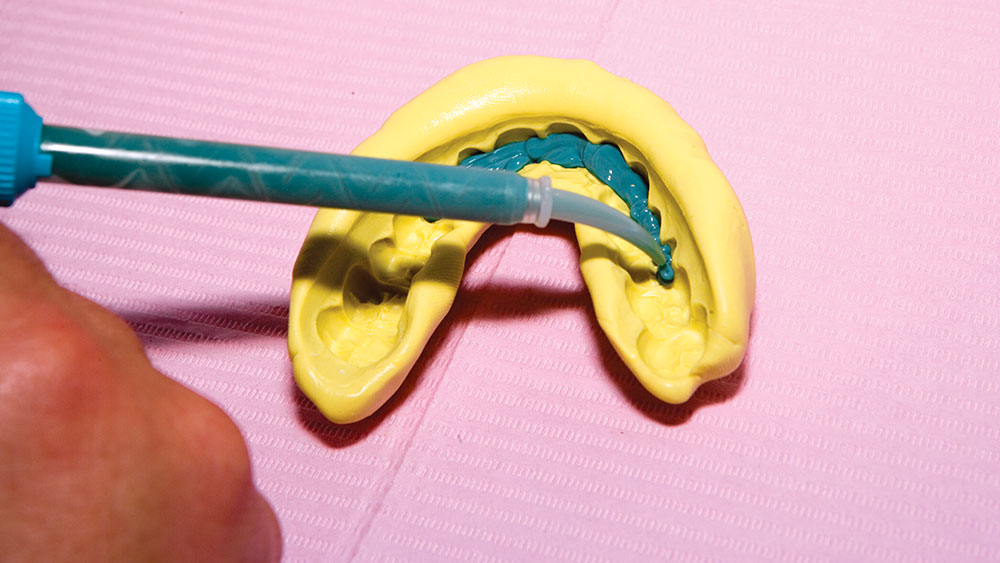

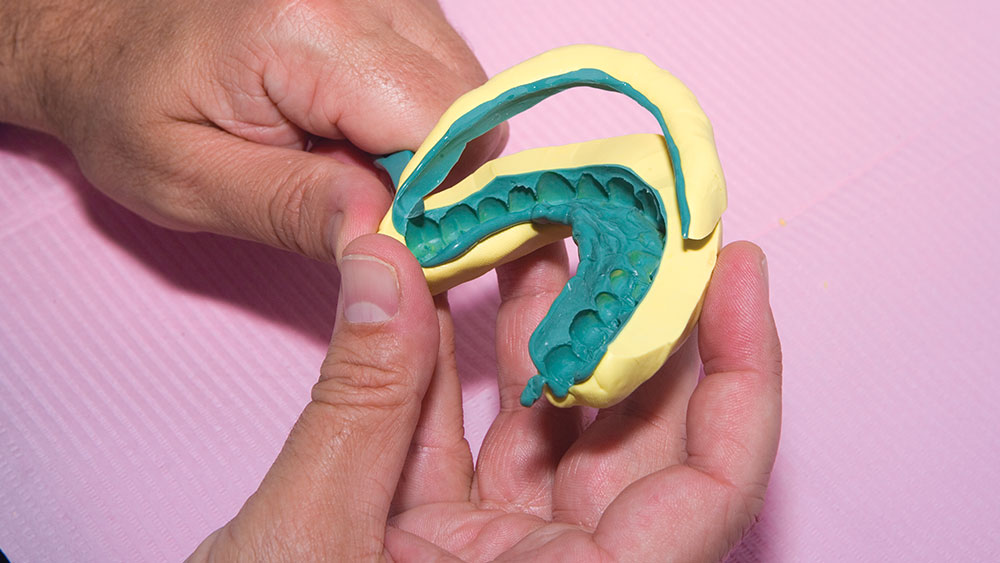

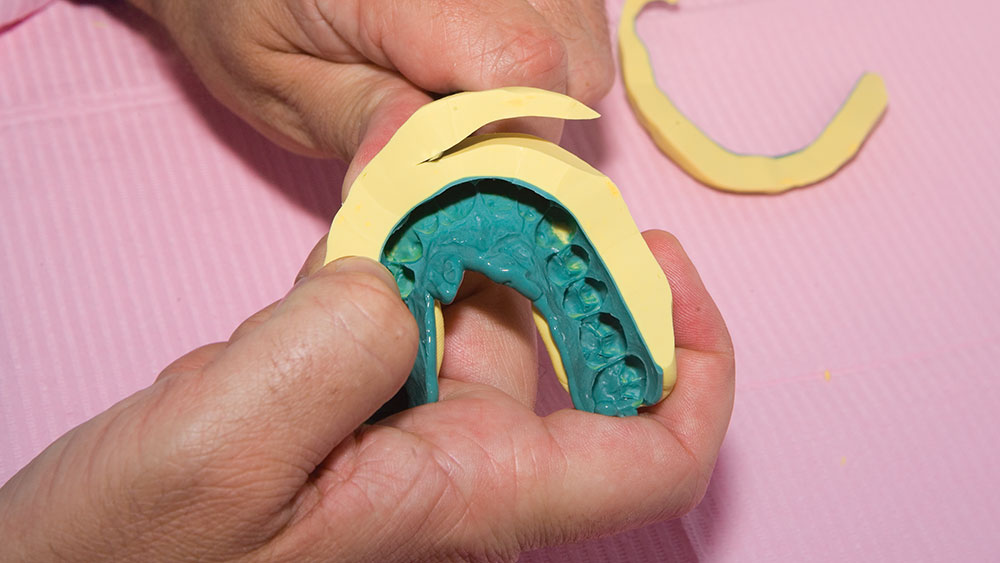

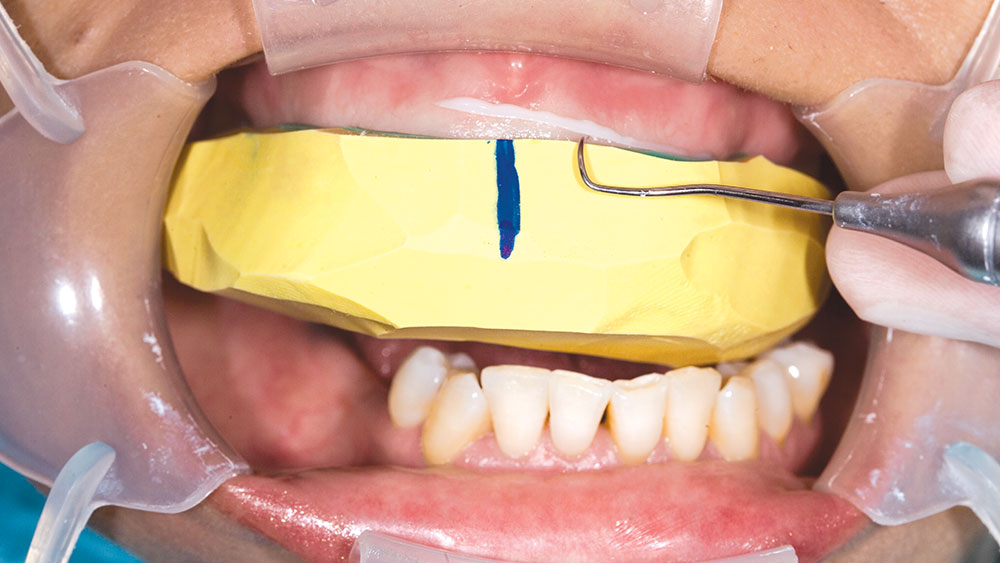

During my 20 years of practice, diagnostic wax-ups have become increasingly important to me. In the beginning, it was merely a sales tool I could show to the patient to demonstrate porcelain veneers. Today, the diagnostic wax-up serves three main purposes: 1) To help the patient commit to treatment by showing them the desired outcome. 2) As a preparation template, it shows me which teeth to prepare and how much to prepare. 3) After years of trying, I still haven’t found a better way to make temporary veneers than using a putty/wash matrix of a diagnostic wax-up.