“The popular mandibular-advancement devices have a greater level of acceptance by patients than the standard nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment in recent head-to-head studies. It is important that these patients be followed by sleep clinicians as these appliances are less successful in controlling sleep apnea when the level of severity is high. Research is needed to determine the patients most appropriate for an oromandibular treatment and when CPAP is the treatment of choice."

Treatment for Snoring and Sleep Apnea: Then and Now

Take a look back at how one appliance helped transform the field of dental sleep medicine.

As we look to improve our patients’ overall health, dental sleep medicine has become one of the fastest growing areas in dentistry. This field began only about 50 years ago, with the advent of dedicated research in sleep that advanced this area of medicine.

Dr. Bill Dement is widely regarded as the father of sleep medicine. He started his career with an interest in dreams and REM sleep. His research eventually led him to establish the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic, a sleep research center at Stanford University, in 1970. According to Stanford Magazine, after it opened, the clinic was soon inundated by patients complaining of extreme daytime sleepiness due not to narcolepsy or insomnia, but to a recently discovered disorder, sleep apnea, in which the patient’s airway would collapse during sleep, causing the patient to wake gasping for air hundreds of times each night.

A decade later, in 1980, Australian physician Dr. Colin Sullivan began work on a project that has played a significant role in how patients are treated today. He used a vacuum cleaner motor and a rudimentary mask to blow air into his dog’s airway to stop his snoring and sleep apnea, and it worked. This was a great place to start because dogs, especially pugs, bulldogs and boxers — as well as Maltese Shih Tzus such as the one pictured below — have restricted airways and tend to snore like crazy.

Sophie Clare experiencing a rare awake (and quiet) moment.

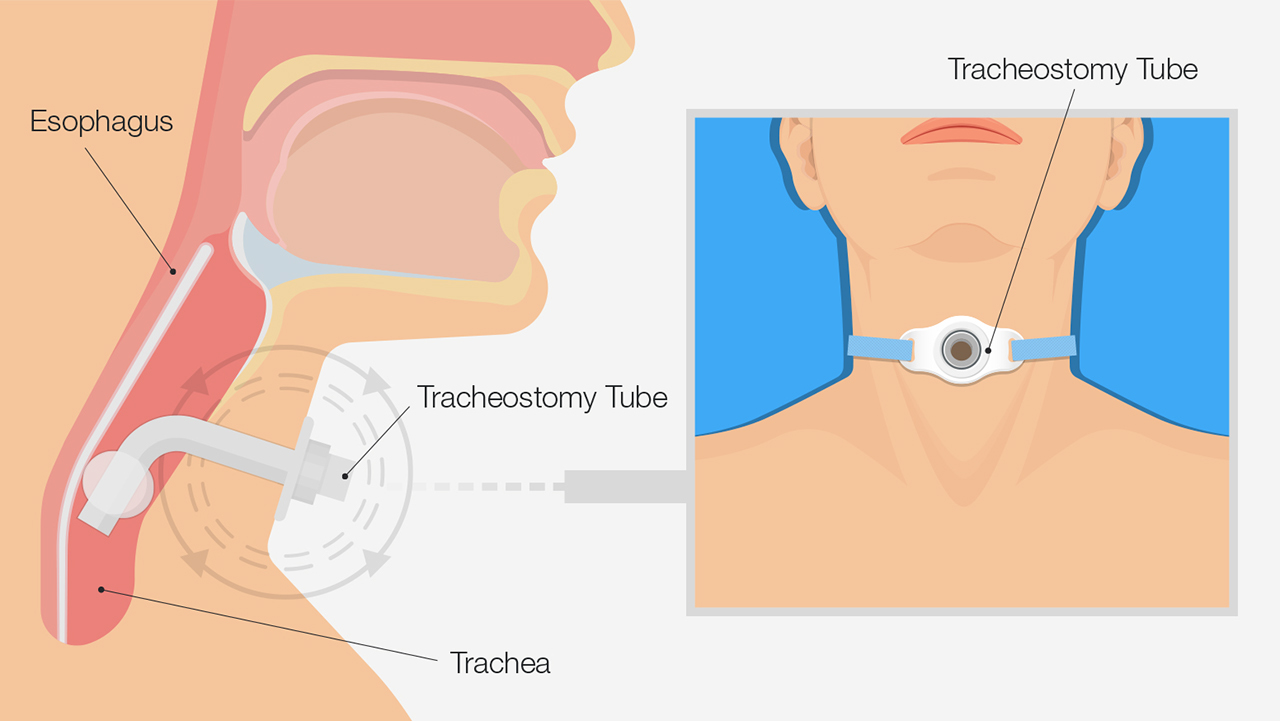

This research led to the development of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), a nonsurgical treatment for human sleep apnea, in 1981. Prior to this invention, the only treatment for severe sleep apnea was tracheostomy, a small incision through the neck into the trachea. With this approach, a tube is inserted to create an air passage that bypasses the base of the tongue and areas of the upper airway that collapse and obstruct the airway during sleep.

Tracheostomy involves a small incision through the neck into the trachea.

CPAP changed the world of sleep therapy. Dr. Sullivan’s invention opened sleep therapy to patients who previously did not qualify for treatment because their condition was not severe enough to warrant the risks of surgery, or the effect of this treatment on the patient’s lifestyle.

Dental Sleep Medicine

This was also an important era for dental sleep medicine. The effect of jaw position and airway had been available in the dental literature for some time. For example, in 1902, Pierre Robin proposed the use of a device (monobloc) with the purpose of procuring a functional advancement of the jaw, dragging it forward to a more advanced position. However, it was the work of Drs. Rosalind Cartwright and Charles Samelson with tongue-retaining devices (TRD) in 1982 that raised dental sleep therapy in mainstream medical publications.

A tongue-retaining device is a mouthpiece that has a suction cup that holds the tongue forward between the teeth. The tongue is reputed to be the main cause of upper airway obstruction. Drs. Cartwright and Samelson showed in their work that changing the position of the tongue improves airway patency and is an effective treatment for sleep apnea. In their research paper, they stated, “The mean apnea plus hypopnea index while wearing the TRD is comparable with the rate reported for patients who have been treated surgically by either tracheostomy or by uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, although the tracheostomy group contained more severe cases.”

Example of a tongue-retaining device that holds the tongue forward between the teeth.

This early work opened the door for oromandibular treatment of sleep-disordered breathing to be considered the first line of therapy for mild to moderate sleep apnea, with the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) releasing its practice parameters and guidelines in 1995. These recommendations came just two years after a Wisconsin study suggested that obstructive sleep apnea affects an estimated 24% of men and 9% of women.

By 1995, more than 100 dental devices for snoring and sleep apnea had been researched and FDA-cleared for the treatment of upper airway obstruction leading to snoring and then sleep apnea. It was around this time that mandibular advancement devices became the appliance of choice for most dentists and their patients. These are the appliances of the modern age of dental sleep medicine.

Mandibular advancement devices (MADs) consist of upper and lower mouthpieces that engage the dentition and can hold the mandible in a protrusive and therapeutic orientation during sleep. This position is selected in order to activate the muscles and ligaments of the oral airway, which creates an increase in the pharyngeal opening. This tensioning and supporting of the tissues prevents the jaw from creating a partial or complete obstruction, which can occur if the jaw falls back into the airway during sleep.

Although MADs had arrived to treat sleep-disordered breathing, the processing time, location of manufacture, and materials made the devices fragile, labor-intensive and expensive. In 1996, Glidewell President and CEO Jim Glidewell, CDT, recognized that dental treatment for snoring and sleep apnea needed to change in order to treat more people, and do it faster and at a lower cost. In order to address this need, the appliances needed to change, and the entire appliance delivery process needed to be optimized.

Increasing Treatment Accessibility for Snoring and Sleep Apnea

The cost and method of fabrication of MADs made dentist-prescribed custom oral appliances too expensive, and this issue was seen as the main impediment to many people receiving care. Therefore, Glidewell applied the core skill of mass customization to the sleep disorders dentistry field, and in August 1996, the Silent Nite® Sleep Appliance was born. The device was not only easy for general dentists and staff to deliver, but also comfortable, adjustable, and inexpensive enough for patients who were on a budget or uninsured.

During this time, the sleep appliances that dentists could choose from were very different compared to the solutions available today. In that era, appliances were generally pressure-formed with metal parts, orthodontic wires and acrylic splint materials, each piece painstakingly hand-worked into a custom mouthpiece.

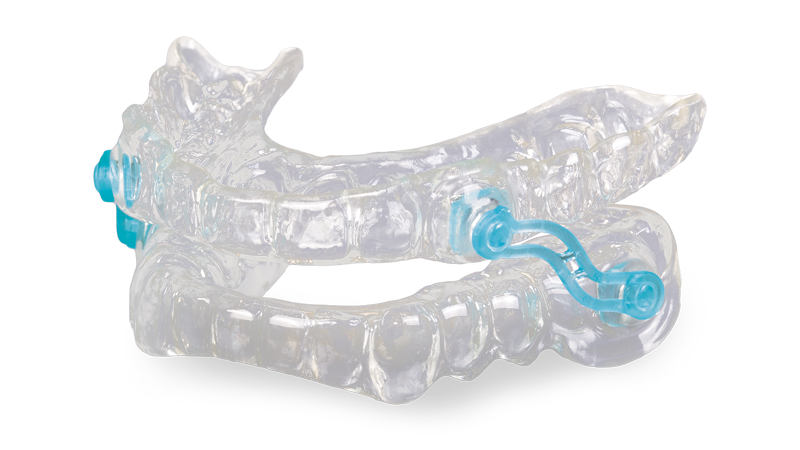

In contrast, the Silent Nite appliance is a mandibular advancement device that consists of two thermoformed mouthpieces: one on the maxillary arch and one on the mandibular arch. The mouthpieces are joined bilaterally with two plastic connectors. The connectors can be replaced with longer or shorter connectors to adjust the mandible up to 6 mm. The flexibility of the materials, and the fact that the upper and lower mouthpieces are not fixed, allows patients the freedom to move the jaw laterally. This is particularly important for patients with bruxism (i.e., those who clench and grind during sleep). If this characteristic is not present, the patient may feel locked in or restricted, which affects patient compliance over time.

The version of the Silent Nite appliance that transformed the field was made in the Glidewell facility in Southern California. The appliance was a hit with general dentists from its introduction. At the time, the launch team commented that many of the first patients using the Silent Nite were actually dentists. Indeed, when some of those first prescriptions came into the lab, often, the patient’s name was identical to the name of the doctor who sent in the impressions and bite registration.

From the photo archives: Here’s an early version of the Silent Nite Sleep Appliance, which was introduced in 1996.

As time progressed and the literature around the dental treatment of sleep disorders became more comprehensive, it was evident that the role of sleep bruxism was even more important than previously thought. Glidewell sought to refine the appliance’s characteristics to build this new information into the appliance. It was decided to increase the mobility of the mandible by redesigning the connectors to allow even more movement. Today, patients who receive Silent Nite appliances can enjoy the comfort of plastic connectors that bend to allow lateral movement, as it was determined that this feature improved nightlong wearability of the device.

Dr. Cartwright said in her 2001 article in Sleep Medicine Reviews:

Oral appliance therapy is considered to be moderately effective in eliminating sleep apnea; however, OAT has better long-term compliance and is used during more hours and nights than CPAP. Yoshida et al. found in their study that 90% of patients treated with OAT for sleep apnea were still compliant after 2.5 years. Compare this with CPAP, a therapy that is considered by many to be the gold standard of treatment for OSA. This therapy, according to one literature review published in 2016, has continued to have persistently low adherence over the 20 years of the study. The authors went on to claim that this state of compliance calls into question the idea of CPAP as the gold standard of care.

The modern Silent Nite Sleep Appliance reflects more than 20 years of clinical feedback used to maximize treatment success.

With over 400,000 cases delivered, the Silent Nite Sleep Appliance is the most successful custom sleep appliance available from Glidewell. The Slide-Link connectors make the appliance comfortable, and the custom fit affords a small design framework that also aids in comfortable, all-night wear. As dentists have reported excellent results with the Silent Nite Sleep Appliance over the years, in 2020, after careful review of the clinical benefits of this device, Jim Glidewell was confident enough to extend additional benefits to dentists who provide oral appliance therapy (OAT) to their patients. In addition to offering the company’s standard two-year warranty against material issues, which is customary with medical devices, Glidewell now offers a money-back guarantee. For clinicians, this results in a direct assurance: The Silent Nite Sleep Appliance stops the snoring or it may be returned within 90 days for a full credit. This extra benefit expands access to care, as doctors can more readily provide treatment with the confidence that it will effectively relieve their patients’ snoring.

Conclusion

The field of sleep medicine was defined in the early 1970s at Stanford University School of Medicine. Innovation in sleep therapy practice has continued as we have come to better understand the physiological and neurological impact of poor sleep patterns. For over 40 years, dentistry has consistently delivered a therapy for patients who require choices in being treated for snoring and mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Patients with chronic sleep conditions require early intervention and treatment options that they can use all night, every night.

It’s no wonder that a device like the Silent Nite Sleep Appliance provided by general dentists has done so well in the field of dental sleep medicine. According to the CDC, nearly 65% of Americans aged 18 and over saw a dentist in 2019. The ability to identify, qualify and treat sleep-disordered breathing in a dental office is excellent, and based on the outcomes reported, this treatment pathway is well received and effective.

To discover the simple, three-step process to screen and treat patients for snoring and sleep apnea, visit glidewell.com/pmad.

More to Know

Dental CE

- Free online CE course by Mark E. Abramson, DDS: “Introduction to Dental Sleep Medicine”

Snoring and Sleep Apnea Article

- Randy Clare, Glidewell: “How to Select the Best Anti-Snoring Solution for Your Patient”

Send blog-related questions and suggestions to hello@glidewell.com.