Speed Dentistry: Fast Is Better — Up to a Point

This article will explore the concept of “speed dentistry,” the practice of doing dental treatments faster and better. In today’s world, just about everyone wants things to go faster. This need for speed extends to many aspects of our lives, including travel, food, data transmission and services. Time is money, and slower times cost more money. Many modern businesses pride themselves on — even advertise — their ability to do things rapidly and do them “right.” Be it a fast haircut, fast cost analysis, fast trades or fast dental care, society wants — even demands — rapid service and high quality. If a procedure takes less time, the individual has to spend less time on that project. Any extra time gained can then be used for doing something else, usually something considered “more important.” We have all experienced the anguish of slow food service or post office lines where the operations are done at a snail’s pace. This can be frustrating and costly, and dentistry is no exception.

Even before they are seated in the dental chair, patients do not want to wait. They don’t like spending long minutes with their mouths open or in uncomfortable situations. Having an uncomfortable procedure done is more tolerable when done with speed rather than lethargy. There is no patient who would rather have a tooth extraction done slowly than with the utmost speed. Our patients expect speed, comfort and convenience. They will flock to dentists who provide these things and shun those who don’t.

Taught to Be Slow

Dentists have routinely been associated with slow procedures. This is in part because a patient experiencing an emotionally charged procedure (e.g., extraction) is under stress and experiencing pain or discomfort — physically and psychologically — so time seems to go slower for the patient than it would if he were experiencing something enjoyable. Consequently, the generally held perception is that dentistry goes slowly.

Modern dentistry, as done by many dentists and their staff, is often practiced slowly; that is, more slowly than it needs to be. For example, Dr. Slow is doing an occlusal amalgam. The dentist slowly sits down, chats a bit with the patient, then slowly puts on some gloves, slowly adjusts the fit, then looks at the bracket table, slowly selects a mirror and explorer, and then slowly focuses on the anxious patient’s mouth. He then looks at the record, slowly adjusts the chair position, lights and his loupes, and then slowly reads the record again. Then he slowly looks in the patient’s mouth at the offending caries. He will take his time examining the tooth, slowly looking at it from several angles, then glancing at the record, then back at the tooth. He has seen it several times before, but just to be sure, he looks at it again — and again.

Talking slowly, Dr. Slow then advises the patient that an anesthetic is needed and opens a drawer, slowly selects a syringe, studies a small stack of loose carpules and selects one. He then slowly takes it in his hands and inserts it into the syringe, checks the fit and slowly examines the tip of the needle as solution is slowly expressed. Then he slowly brings the syringe to the patient’s mouth, elevates the lip, slowly examines the injection site and then slowly inserts the needle into the mucosa, slowly injecting as he slowly drives the needle tip deeper into the tissues. Taking a minute or so, he then finishes the injection while he painstakingly moves the syringe from side to side. He then slowly withdraws the needle and syringe, taking his time to insert the safety cap back on the instrument. A 5- to 10-minute wait ensues for what is deemed “good anesthesia.” After asking the patient several times if he is numb, poking at the gingiva and any other tissue within range, Dr. Slow lifts his handpiece and slowly looks at the bur, then looks away and toward his bur block for an appropriate bur. He might look at several burs, slowly considering each one before he makes his selection, and then slowly pick up a chuck tool to loosen the old bur and slowly insert the new bur. This process can go on and on for what seems like forever! I’m sure you get the idea. Instead of taking five minutes, Dr. Slow takes 30 minutes to do a simple restoration. We are all more or less guilty of this type of patient abuse.

Why do we do this? Why is practicing dentistry so slow and methodical? Why must it take so much time when it really is not necessary? The reason is simple: We were taught to be slow in dental school. How many times were we told by instructors, “Take your time and do it right” or “You’re doing this too fast”?

When dental students are first shown a procedure, it is usually demonstrated slowly to ensure comprehension. It is then practiced slowly. Rarely, if ever, are we told or taught to speed up the process. Unfortunately, this dental school experience transfers over into real life and our dental practices. Certainly, when we have a crowded schedule or have to leave the office early, we speed up and push a bit, but this is an occasional effort, not a continuous one. We need to be consistently faster because it is good for our patients, ourselves, our staff and our profession. With the right training, equipment and mindset, we can all be practicing speed dentistry.

Advantages of Speed Dentistry

The faster you do something, the quicker you will finish. If you are torturing (treating) a patient, the faster you do it, the less discomfort the patient will feel over the length of the visit. If you are being paid for a treatment and you do it quickly, then you will be making more money, faster. If you treat 10 patients an hour rather than 10 patients in four hours, you will be going home earlier and richer. The patients will be better served because they will not have to wait for treatment, and they will spend less time in the chair and experience less stress. Physiologically, as adrenalin secretion or stress suppresses the immune system, less patient stress means less adrenalin secretion and faster healing.

Another advantage is that you pay less for your staff because they work fewer hours. However, if you choose to spend the same amount of time in the office as you did doing slow dentistry (same basic overhead), you will be able to treat more people and thus increase your income, try new techniques you previously didn’t have time for, study or give more to charity. Speed dentistry has its financial as well as professional advantages.

Many people object to the concept of speed dentistry because they believe slow is better than fast, equating reduced speed to precision. This began in 1900 America with a great surgeon, Dr. William Halsted, who, after having a stroke, perfected his technique of general surgery by methodically going slow. Compared to the slip-shod, microbe-contaminated surgical techniques of the Victorian era, the new Halsted technique — along with dependable anesthesia — produced fabulous results. Unfortunately, it had an effect on dentistry. In most of our dental school experiences, instructors believed that procedures done rapidly would lead to more mistakes and lower quality, as well as potential injury to the patient or the dentist. They encouraged “slow.” That concept is not held true today, especially in practice. Doing dentistry rapidly, if you are adequately trained, can be done safely and with a high level of quality and patient comfort.

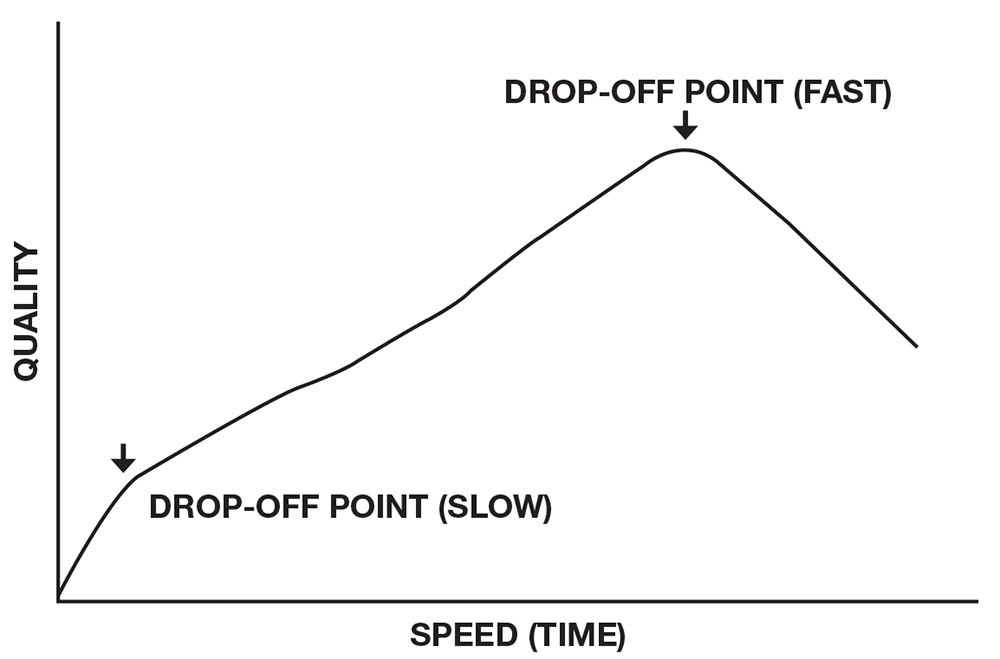

The Drop-Off Point

The drop-off point is the point in a procedure where your quality or control suffers. For example, if you are carrying a tray of filled wine glasses and walking a 40-meter path over uneven ground, you may spill the drinks if you a) walk so slowly that you spend an inordinate amount of time, thus becoming unsteady and fatigued or b) walk so rapidly that you lose control of the tray or trip, thus shaking it and spilling the cargo. These points are termed “drop-off points” because you lose control and quality suffers catastrophically. The area between the too slow and too fast drop-off points is where you want to be with your speed dentistry technique, and the closer you are to the too-rapid drop-off point without reaching it, the faster you will be giving quality treatment.

Here’s another example: If you drive to a destination on city streets going 15 mph, it will take you longer to get there than if you drive at 30 mph. The traffic will pile up behind you, some cars may pass inappropriately and irate drivers my become distracted trying to flip you the bird or honking. Some people may even become confused and hit your car. You will probably be safer and drive the journey more efficiently if you go 30 mph. Sixty mph is too fast, 30 mph is not, yet many dentists do their dentistry at 10–15 mph speeds because they believe going slow is good.

How can you tell when you reach your drop-off point? You’ve reached it when you start to make errors and mistakes. When you see this happening, ease off a bit and slow down. Speed affects different people in different ways, so you will have to test yourself. No one can tell you how fast to go.

It is important to recognize and not exceed your slow and fast drop-off points. As long as you stay in that range, your treatments will be of high quality. With some practice and new equipment or techniques, you may even expand your drop-off point to higher levels. The message is that slowness is not always good, and speed is not always bad. Be careful not to confuse slow speed with quality dentistry. Doing dentistry at a snail’s pace can often be harmful to the patient and to you, the dentist. For example, slowly doing a reflected surgical flap procedure in 40 minutes is more harmful to the tissues than the same flap procedure done in just 10 minutes. Speed dentistry is beneficial, as long as you do not exceed your drop-off point (Fig. 1).

It is important to recognize and not exceed your slow and fast drop-off points. As long as you stay in that range, your treatments will be of high quality.

Doing Speed Dentistry

How does one increase their speed in dentistry? Just doing a procedure rapidly is not sufficiently beneficial because it often becomes a hit-or-miss adventure. Carefully planning how you will increase your speed and repeatedly performing at that level will yield permanent and controllable results. You need to think about how you will speed up your treatment technique. Ask yourself what you are going to do, what instruments you will need and what materials will be necessary. Plan what you will do if this or that happens, such as the enamel breaks or the patient moves. Then have everything ready.

Every dentist works differently, using his own techniques, instruments and other customized methods of doing dentistry. Everyone is unique and produces different results, even with the same patient, materials and techniques. There is no one method for speed dentistry. Dentists must identify a variety of faster techniques, try them out to see what works and what methods are effective, and then perfect them. They must execute a little faster here, a little faster there, until they see substantially improved results.

There is no one method for speed dentistry. Dentists must identify a variety of faster techniques, try them out to see what works and what methods are effective, and then perfect them. They must execute a little faster here, a little faster there, until they see substantially improved results.

Here are some reliable and generally successful ways many dentists have used to increase their speed and begin practicing speed dentistry:

- Simply think you will do dentistry better and faster. Many dentists have never considered this concept, so they just continue to work slowly like they did in dental school. Once you decide to do your dentistry more rapidly, you will.

One way to check how you are doing is to place a timer in each operatory. Time how long it takes you to do a procedure. Log the time. Try to do it a bit more rapidly the next time, and the next. Experiment. Test different ways of doing a procedure or handling a patient. Use that timer with every patient and every procedure. Keep records and analyze your results. Once you are timing yourself, you will begin working faster and doing speed dentistry. Remember, the true measure of speed dentistry is the amount of time the patient is in the chair. It doesn’t help much if you quickly do a restoration and then squander all the time you saved by telling stories or cracking jokes with the now-completed patient.

- Identify those procedures that take up most of your time and then decide how you will speed up the process. Can you do the treatment differently and shave off a second or two? Can you use fast-set amalgam or a stronger curing light to speed up your restoration technique? Will special instruments or preset trays increase your speed while maintaining quality?

For example, use locking pliers with a cotton pellet already attached. It is faster than stopping your procedure, hunting for a cotton pellet in a capped dispenser (requires uncapping and recapping), selecting the pellet with your cotton pliers and then using the instrument. Save 15 seconds using this technique. Now, if you do it 30 times a week, 48 weeks a year, you do the math on how much time it saves.

- Quit talking so much. Talking sucks time. If you must talk — keep in mind, most patients appreciate a few words — speak while you are doing something productive. Avoid talking about yourself. Instead, talk to your patients about their lives. Everyone likes to talk about themselves, so let them. If someone needs to be calmed down or relaxed, have your dental assistant do most of the work. If you save 30 seconds of idle talk per patient, and you see 20 patients per day, four days a week, 48 weeks a year, you will save 32 hours of chairtime per year. Think about how much you make in one hour of chairtime. And that’s just 30 seconds. Go for more.

- Increase the air pressure of your dental handpieces to 60–80 psi. They run faster, cut faster, and you finish faster. My experience is that the handpiece cartridges will also last longer, despite the common industry recommendations to keep the pressure at 30 psi.

- Use sharp instruments. Sharpen the edges of your plastic instruments, the tips of your explorers, spoons and other hand instruments. Scalers and curettes must always be sharp. Do the sharpening before the patient is in the chair, not during the visit.

- Use topical anesthetics and rapid-induction hypnosis anesthesia (waking hypnosis) rather than injecting — and waiting — for every little cavity prep or procedure. Using fast-acting medications and materials will save you time.

- Move faster and have your staff move fast, too. If they resist or complain, fire them. A slacker with a mopey attitude will never change. You are operating a service business, not an employment depot for the low and slow of our society.

- Analyze each movement during a procedure. Is it necessary? Is it needed? Can you do without it or change the procedure to omit it entirely? For example, many practitioners wipe instruments on the patient’s bib. This takes a few seconds to do and then re-establish focus on the tooth being treated. Instead, place some gauze in the patient’s mouth and wipe your instrument on it there. This positions you closer to the action, takes less time to do, does not divert focus out of the mouth and is probably more sterile. Saves a second — or four.

- Have prearranged instrument setups for each procedure. This is infinitely faster than picking a multitude of instruments out of a chest of dental drawers with the patient watching. When the patient is in the chair, do dentistry. Don’t waste your time and the patient’s time setting up to do dentistry.

- Determine if there are simpler treatment methods. For example, seventh-generation bonding is an all-in-one technique that is considerably faster than a fourth-generation technique of separately etching, separately priming and separately bonding a composite. Saves two minutes.

- Don’t spend time “making it pretty” if it doesn’t matter to the patient. Carving secondary anatomy in a composite or amalgam wastes significant time and will do nothing to improve the restoration. If you want to be an “artist,” paint or sculpt during your free time or off hours. Does amalgam really need to be polished? How about composites? Do you need frequent recall appointments for an asymptomatic, healthy patient? Do you need to do all those adjustments? Can you place dissolvable sutures instead of using silk sutures and scheduling an extra and time-consuming suture-removing appointment? Don’t waste your time doing extra, unnecessary work.

- Look at the treatment area (gingiva, tooth) intently, but just once. Then treat. Don’t waste time looking, then relooking, then cleaning off your mirror to look again. Concentrate and don’t play.

- Don’t do services that take more time than they are worth. For example, if maxillary third molar endo on a difficult patient takes too much time and energy, refer it out to someone else. If you produce $1,000 an hour at the chair and take two 50-minute sessions to do a molar endo for which you are charging $900, then you are losing big money and not helping the patient. Refer the patient to someone who can do the job in 30 minutes. You can’t do it all! Dump the time-consuming procedures.

- Get rid of difficult patients. Difficult patients take up lots of time. Spending time to argue, constantly reassure and repeat slows your work and forces your other patients to wait and possibly suffer. Send your difficult patients a note saying, “Because of our communication problems, I cannot continue being your dentist.” You don’t need them or the time-sucking referrals they may bring. If a patient wastes your time by often arriving late or breaking appointments, get rid of them. If you can’t bear to kick them out of your practice, then charge them double: they’ll leave. The ones who truly love you will stay and pay the bill. Another technique is to have them wait one hour in the reception room before you see them. They’ll get angry and leave.

- Prepare a series of information sheets with drawings or photos on each procedure you will do. Personally giving an info sheet to a patient as you are going to another operatory and asking him to “look at this, John” saves a lot of non-productive chairtime you would otherwise spend describing the dental work you will be doing. Practice discussing dental procedures or treatment options using the most direct, simplest way you can communicate. Long-winded lectures are boring to the patient and wasteful, and they should be eliminated. For example: “John, we can save your tooth with root canal treatment costing $700 or pull it out for $200. Your insurance will pay half. You will pay the other half.” If the patient dawdles, give him some speedy direction, “John, if it were my tooth and I had the $350, I would save it.” Save time by practicing your role in these situations so you will be prepared to quickly present yourself when the day comes.

- Make use of hand signals to your staff. For example, waving an index finger means to mix the cement. This saves time, especially when you are communicating with your patient and need to communicate with your dental assistant at the same moment.

- Control phone calls and other non-essential interruptions. You can call them back at convenient moments. Grabbing a phone in the middle of an operation is a time waster, foolish, and insulting to the patient and staff.

- Do as much as you can in one sitting. Try to avoid wasting time by getting up, walking out, coming back, re-gloving, re-washing and reappointing. Do it all at one time.

- Have spare instruments available for quick access. If you drop a mirror or bend a needle, you should have a replacement within easy reach. Do not lose time waiting for your dental assistant to run and get another instrument in the next room.

- Always be well stocked with an accurate and dependable supply of disposables, instruments and other dental materials. There is no value in running out of widgets when you need them. Being well stocked is common sense. Devise an automatic inventory system and implement it.

- Have redundant systems that can quickly be utilized in case of malfunction. If your compressor or vacuum goes out, you can simply turn on your spare. If you don’t have a spare, you will waste time and lose money. Be sure everything is hooked up and ready to go. Having a spare compressor in your garage doesn’t help you in the office. Quick plumbing disconnects and standard electric plugs/sockets can make it possible to switch equipment in a few minutes. This converts a time-wasting disaster into a minor inconvenience. It’s going to happen to you some day, so be prepared.

- If it takes too much time to learn or use, you don’t need it. Our lives are filled with “labor-saving” gadgets, which we buy only to find out that they take too much time to use. “Modern” and “new” is not always the best. Software is a prime culprit. Beware of the time-wasting learning curve. Keyboard entry may be considerably slower than quickly scribbling on a record sheet. If you have to computerize, let your staff transfer the patient’s written records to the computer.

- Keep appointments to a minimum. If the patient has four restorations to do, do them all in one appointment, if practical. Don’t schedule another appointment if you don’t have to. Reappointing takes up considerable time: greeting the patient at the door, seating the patient in the dental chair, looking at the patient’s record, chatting with the patient, etc. With your speed dentistry technique, you can do more work in less time. Your patients will appreciate it.

- Inject anesthetics rapidly. Some dental instructors say it is better to inject slowly, but they are wrong. Why do it rapidly? Because it takes less time. Patients may feel a bit more pressure, but they will suffer less emotional trauma if you inject in 15 seconds instead of giving a slow, torturous 65-second injection. If you are going to inflict pain, the faster you do it, the less net discomfort there will be.

- Move with a sense of purpose. Avoid wasted movement.

Be Humane

Let’s face it: Everything in dentistry is not about time and money. You may confront a situation in which you must take more time to do a procedure or talk to a patient. If necessary, you must sacrifice cold efficiency for good humanity. However, you must keep these time sinks to a minimum or direct them to that portion of the day when you can take a little more time. Sometimes a lonely elderly patient wants to tell you a joke that goes on forever, or worse, talk about their divorce or operation. Do your best without insulting the patient. Devise techniques for such situations. Just keep it controlled.

Problems

Speed dentistry, like any endeavor, has advantages and disadvantages. If you are going to speed up, you will use more energy. If you speed up gradually, your stamina will increase, but you may be more tired by the end of the day. That is the cost of speed dentistry. Of course, if you do two days’ worth of patients in one day, you can take another day off to rest and recover with no net financial loss. Decide what you are going to do with that extra time and money. If the way you decide to use it is productive — great. If it is self-absorbed and abusive, such as spending your newfound time at the local bar, then perhaps you should go back to the office. Think about it. Speed dentistry is not for the lazy dentist.

Start Now

So where do you start? As previously suggested, start by realizing how speed dentistry will help you, your patients and your practice. Get some idea of how long it takes to do a procedure or see a patient. Start with exams, cleanings and restorative procedures. Using a timer (or a group of timers), identify how long it takes to do a procedure. Make some changes. Time yourself again. See if you can shave off some seconds or maybe even a minute or two. Use quicker materials and techniques. Keep track of the time. Perfect your technique. Watch for your drop-off point. You may become a fast dentist or a good dentist, but what you really want to strive for is being a fast, good dentist. This is an art form. Try it and good luck!

Sections of this article come from the book “Speed Dentistry,” by E.J. Neiburger, DDS. Andent Publishing, 1000 North Ave., Waukegan, IL 60085. Copies are available at andent.net.

Dr. Ellis Neiburger is a general practitioner in Waukegan, Illinois. Contact him at 847-244-0292 or eneiburger@comcast.net.

© 2012 by E. Neiburger. First publication rights granted to Chairside® magazine.