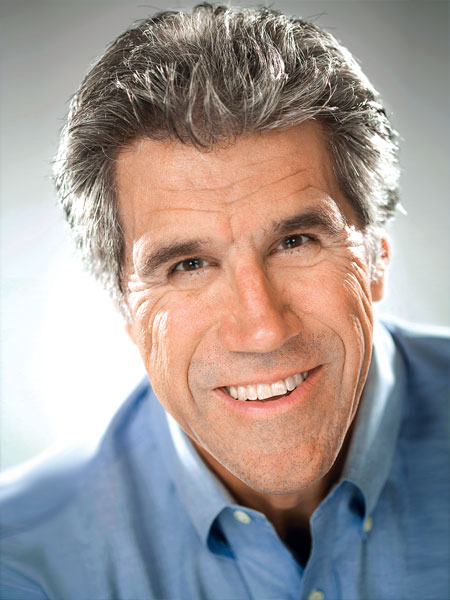

One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla Interview with Dr. Paul Homoly

Dr. Michael DiTolla: Welcome back, Paul! Today, the topic we are going to discuss is prosperity.

Dr. Paul Homoly: Mike, this topic goes back to our previous article when we talked about the cultural center of dentistry. The cultural center of dentistry, of course, is the pursuit of clinical excellence. A big part of that cultural center is the concept of patient education. These are central core beliefs that we have as an industry, as a profession, that what we’re about is producing and sustaining clinical quality. And as a part of that, a way to advance that, is educating our patients. These are strong beliefs that drive our behavior.

The cultural fringe — that is, what’s not at the center but what plays at the edges — is the concept of prosperity, the concept of understanding patients, and the concept of influencing patients. To say that prosperity is not at the center of the culture of dentistry is a pretty accurate statement. We don’t learn about the concept of prosperity in dental school. There are even some states in this country that don’t give continuing education credits for practice management courses or financial planning courses. I just got off the phone with one of the leaders of the Academy of General Dentistry, and he said that one of the topics that draws the poorest attendance are courses on practice management focused on dentists running more a successful practice. So, today, I really want to go after the concept of prosperity.

Prosperity is about having the energy to succeed. Prosperity is about combining a willful act with an aspect of hope thrown in. And that prosperity not only means financial success, but prosperity in all aspects of our life. And a big part of the pursuit of prosperity is how we talk about it — language is symbolic. How we think and how we talk largely shapes our experiences.

To start this article, I’d like to ask you to put yourself in the mindset of an average general dentist. Let’s say that your collections are $900,000 to a million dollars a year. Would you say that’s about normal, Mike? What’s your sense there?

MD: I don’t know … that sounds a little high. I would say $800,000 might be closer to the average, but that’s just a guess.

PH: OK, put yourself in that position — you’re an average dentist and your annual collections are $800,000. Here’s what I would like for you to do: think about the ideal case, one that you really enjoy treating. Think about it in terms of the technical characteristics. Is it a crown and bridge case, a combination restorative-perio case, a cosmetic case? Think about this ideal case and ask yourself, what is the total treatment fee for this case? Take into account all fees, including specialist fees. For example, if you enjoy doing implant dentistry, but you don’t do the implants, you do the prosthetics, your ideal treatment fee would include the specialist fees to do that case. Same thing with perio, same thing with ortho. So, think about that for just a few seconds. You’re the average general dentist; what type of case do you enjoy doing most? Describe it to me technically. Then give me a sense of the total treatment fee.

MD: I would like to do a case that’s a combination of restorative dentistry and elective dentistry. I really like replacing old crowns on #7 through #10 and then no-prep veneers on #4, #5, #6 and #11, #12, #13. The fees on that are probably going to be … we’ll say, $800 for the crown or $3,200 for four of those, plus $800 for each of the veneers. So the total case is going to be $8,000, give or take some ancillary services.

PH: OK, so we’ll call it an $8,000 fee. That’s the average guy. Now, let’s ask the same question to the above-average dentist. Let’s look at a dentist who’s been to the institutes, who owns all the adjustable articulators, CEREC® units, belongs to a restorative study club or Seattle study club, has been in dentistry for a full 15-plus years, and understands occlusion, perio and cosmetics really well. Maybe the dentist is a Fellow or Master in the AGD. What’s an ideal case for a dentist like this?

MD: Well, this dentist is probably going to enjoy the challenge of a multi-disciplinary case. That’s going to require a couple of implants here or there, certainly some cosmetic work around a few teeth, restorative work on some other teeth, probably changing the bite to improve function. A couple of teeth may need to have some endo retreats. If you look at all the fees combined, you’re probably in the neighborhood of $20,000 to $30,000 for a complete mouth.

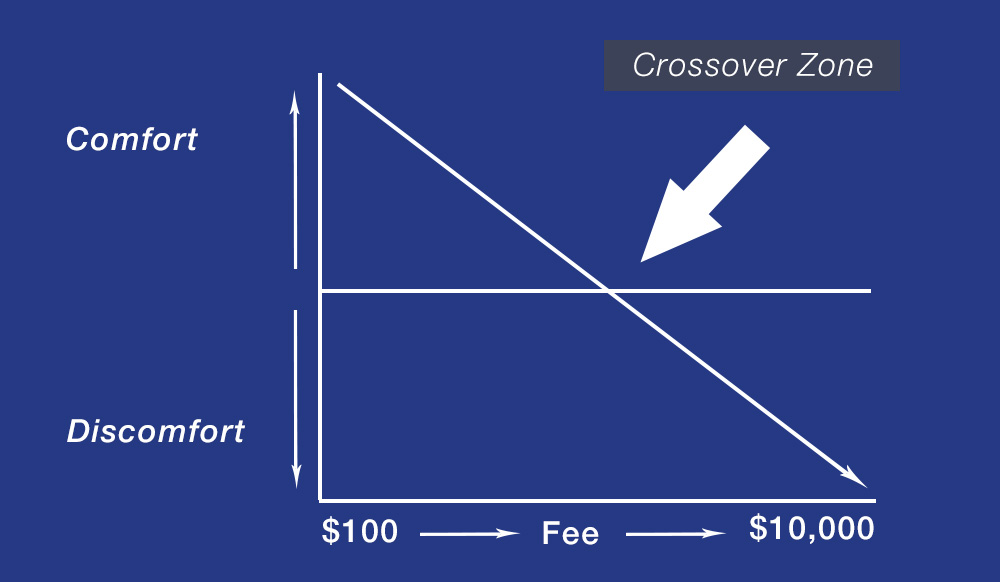

PH: OK, we’ll call it $25,000. So, we got the average fee for the average dentist’s ideal case, between $3,000 and $8,000. We have the ideal case for the more advanced dentist at $25,000. Mike, what I’d like for you to do now is look at that slide I sent you (Fig. 2).

The Crossover Zone is an illustration of the cultural behavior of dentists relative to talking about money. What this chart shows is that in the culture of dentistry the higher the fee, the greater our discomfort is in discussing that fee. For example, let’s say the fee is $1,000. You notice that line is in the comfort zone. The horizontal line that goes through the center of the chart, parallel to the horizontal axis, is the dividing line between a dentist being comfortable discussing the fee and the dentist being uncomfortable discussing the fee. This is not the patient reaction. This is how the practitioner feels when he or she is discussing the fee. So at the $1,000 level, the dentist feels comfortable talking about the fee. This is just an example now, Mike. So $1,000, you’re comfortable; $2,000, you’re comfortable; $3,000, you’re comfortable; $4,000, your knees are beginning to shake a little bit; $5,000, you’re beginning to breathe hard; and at $6,000, you are now in the zone of discomfort. You see how that works?

The Crossover Zone is an illustration of the cultural behavior of dentists relative to talking about money. What this chart shows is that in the culture of dentistry the higher the fee, the greater our discomfort is in discussing that fee.

MD: At $10,000, you are visibly sweating.

PH: You’re visibly sweating and you show it in your body language. You’re breathing hard, you’re not making eye contact with the patient.

MD: You’re trying to use a lot of dental technical terms and not really giving them answers to questions that they have.

PH: Exactly. Hiding behind your visual aids — all of that. Now, I showed the scale from $1,000 to $10,000; it could be $1,000 to $50,000. This illustration is for diagrammatic purposes only. Now, I’d like for you to wear your average general practitioner hat again, go back to that average dentist. Where do you cross over? That is, at what fee do you go from comfortable to uncomfortable? As you’re quoting the fee — you’re the average dentist now, Mike — where does it get uncomfortable? Where is the Crossover Zone?

MD: Probably right around $4,000.

PH: OK. And put your hat on as far as the dentist whose ideal treatment plan would be $25,000. Where are you crossing over? Where’s this AGD Master, graduate of the Pankey Institute, graduate of the Dawson Center, owner of the articulators, CEREC units, lasers — where is this dentist crossing over?

MD: Well, he or she is still a dentist, albeit a very intelligent one. But intelligence isn’t the issue here. I’m going to say this dentist gets uncomfortable at the same spot — $4,000.

PH: You’re exactly right.

MD: We are, after all, just humans and dentists.

PH: You’re exactly right.

MD: I don’t know that any amount of technical training can get you to the point where this stuff no longer affects you, or these numbers no longer affect you. I can guess where you’re heading with this — something along the lines of patient education can’t make patients ready. Clinical education for the dentist, and the pursuit of clinical excellence, does not mean that you can ignore what’s going on inside your own head when you go present these numbers to a patient.

PH: Exactly right. I’ve been teaching this in seminars for decades, and what’s amazingly consistent is the Crossover Zone among dentists. Now, there’s two numbers. Let’s look at the first number. The first number when I do this exercise, dentists are usually going to be in that $4,000 to $6,000 range. They go off to the institutes and learn to treatment plan implants instead of partial dentures, veneers instead of three-surface composites. They learn to take cases that they would typically treatment plan for $3,000 to $4,000 at $10,000 to $12,000. How much more comfortable is the dentist quoting that treatment plan?

MD: The dentist actually might be doubly comfortable because it’s a bigger number. But he or she is also now quoting a fee for something performed very few times, as opposed to quoting a fee for a partial denture that they’ve done many times.

PH: You bet. And that’s exactly what happens — dentists come back with new technical knowledge that’s helped their hands but hasn’t helped their hearts. They haven’t changed on the inside; they haven’t embraced the concept of prosperity. That’s the point of the article.

MD: Well, they would have gone to a practice management course, but organized dentistry has sent them the not-so-subtle message that it’s not very important — you don’t get any recognized credits for going to that.

PH: Right, that’s why this concept of prosperity is on the fringe. And why take something that’s on the fringe when you can take something that is at the cultural center? Typically, what I see, Mike, is that the treatment plan fee for the ideal case is anywhere from two to five times greater than the dentists’ Crossover Zone. And that creates a tremendous amount of stress with the practitioner. A great exercise for your readers is to teach the Crossover Zone to their team. The dentist will explain the concept of the Crossover Zone, like I did to you, then each team member working independently, not as a group — it can’t be a group, it has to be as individuals, with a piece of paper and a pencil. And the dentist explains the Crossover Zone and asks the team point blank: “Where do you cross over? What number do you get nervous about?” And then the team needs to immediately write the number down. They can’t be talking to each other. Once they start talking to each other, then you get this community-think and you don’t get real numbers.

MD: Exactly, write it down on a piece of paper, and it should be a private vote. You know everybody is going to have different numbers. And you know that most of your dental staff, if they went to the physician or veterinarian and got a $5,000 to $6,000 fee quote, would be blown away, too. So, it’s probably happening with staff members in your office.

PH: Sure, and I like the idea of a secret ballot. They write the number down and they hand it to the dentist. Then, the dentist takes these numbers and averages the team crossover, OK? He looks at all the numbers, adds them up (he does not include his own), and averages them. What you get is an office crossover number — that is the prosperity culture of your practice. These are the beliefs that are driving the discretionary behavior, Mike. These are the beliefs that when Suzanne, the dental assistant, is sitting next to Mrs. McBucks, the lady with the big diamond rings who rolls her eyes about the fee. And the dental assistants and other staff oftentimes have the opportunity to discuss fees in the absence of the doctor. It’s that prevailing culture and the practice that will largely determine what that dental assistant says, how they say it, and how they deliver the message. Does that make sense?

MD: Yes, it does make sense, and I’m beginning to realize that this is may be more of a make or break moment than having the dentist quoting the fee. What happens when the dentist is gone and the dental assistant, who’s perceived as a peer, reacts to whatever the patient says about the fees?

PH: Ha, you bet. It’s like going into a restaurant, Mike. Let’s say you and I go to a restaurant, we look at the menu, and we’re not sure what to order. When the waitress comes I ask her, “How is your salmon today?” She kind of shakes her head, and says: “You know what … if you want fish, I would go with the mahi-mahi. But the salmon, I don’t think it’s as fresh today as it usually is.” You’re going to believe that because the waitress is in direct contact with the customers. But when the chef comes out and you ask that same question, he might say: “Oh, it’s a miracle. It’s wonderful!” Well, he doesn’t interact with the customers, the waitress does. And in many ways, the dental assistant, the dental hygienist and the dental receptionist offer that second party endorsement and authentication of what is really going on in the office. So you’re right on. It’s the culture that prevails in your practice that’s largely going to determine how much stress is surrounding money.

MD: Not only that but the waitress told me the truth about the salmon, and then gave me her opinion, so I trust that. Almost as if the dental assistant were to acknowledge, “That is a lot of money, however…” — that kind of thing. I also don’t see the waitress being emotionally connected to the end product, taking it personally how it’s cooked or not cooked. It just happens that the mahi-mahi is better than the salmon, whereas the chef (i.e., the dentist) is emotionally connected to it. That’s one of the reasons my dental assistant tries in all restorations without me in the room. I don’t want to put any pressure on the patient to look at the mirror and go, “Wow, these look fantastic” because I just said how fantastic they look. I want them to have an authentic conversation with my dental assistant with me out of the room. Then, there’s no pressure for them to say what they think I want them to say.

PH: Ah, very wise, very wise. So then, what’s the impact of having the culture of your dental practice where the crossover number is lower than the treatment plans you’re presenting? Number one is increased stress. Number two is erosion of confidence — as stress prevails, more and more patients are going to refuse treatment because they sense the stress in the dentist and team members. When dentists don’t give off an aura of confidence when talking about money, people become suspicious and that’s when they leave. To have a lower crossover number than your treatment plan is an avenue to lose patients. Once dentists realize this, often unconsciously, they stop quoting fees above this Crossover Zone. That is, the dentist pulls back on treatment plans and starts offering care based on what is comfortable, not so much on what the patient needs or what the patient can pay. That, over time, will lead to cynicism. The dentist will begin to believe that the population they serve is a bunch of low-lifes with low dental IQ, and they don’t value you or your dentistry. And, ultimately, that will lead to surrender. Dentists will say: “Dentistry isn’t what I thought it would be. I’ve missed the boat. I’m too old to change. If it weren’t for the damned insurance companies, then this would be great. This economy is ruining my practice…” Everything kind of swirls down the drain and the sense of prosperity is replaced with a sense of desperation. And as an opinion leader and consultant in dentistry, Mike, this is something that I see all the time. This domino effect that goes from stress, to erosion of confidence, to loss of patients, to avoidance of treatment plan, to cynicism, and ultimately ends in surrender. We see it all the time.

Let me give you a few more scenarios that can occur around this Crossover Zone. Let’s look at what happens when the doctor is crossing over significantly higher than the team. By the way, when I average Crossover Zones from the teams — and this is again a decade of empiricism, a decade of doing this and averaging the number from literally hundreds of practices — most teams cross over between $6,000 to $6,500. I don’t know why that is, Mike.

MD: That is a really narrow zone … that is pretty amazing.

PH: It is amazing to me, and I see it consistently when I do workshops.

MD: All these dental team members with different family backgrounds, different schooling, different training and work experience, and they all tend to cross over within $500 of each other. Amazing!

PH: It is, Mike. When the dentist crosses over significantly higher, three to five times or more than the staff, it really erodes the staff’s confidence in the presence of patients. The staff members don’t want to be alone with patients when they’re talking about money because the staff members are very uncomfortable with the fees. On the other hand, when the team crosses over higher than the doctor that is also a disaster. Why? Well, take the scenario where, let’s say, the team is paid on performance and a monthly bonus is involved based on collection. The doctor is doing some crown and bridge, all of a sudden — BAM! Tooth explodes and now you have a root canal, post, buildup and crown that weren’t in the original treatment plan. The doctor’s going to need to go in there and increase the fee. He or she’s already crossed over on this case, and adding additional fees becomes very uncomfortable. So, the dentist tells the dental assistant: “We’re not going to charge for this. We’re not going to charge for that.” And that gets communicated to the front desk. What do you think that does to the morale relative to the pay-for-performance bonus system?

MD: Considering that their bonuses are based on collections, it’s like the dentist just opened up their purse and took money out of their wallet. It’s just a total lack of team effort and self-sabotage, team-sabotage, you name it.

PH: Yeah, you bet. Really, the foundation of what we’re talking about is becoming aware of our own aspect of prosperity. When I was probably a little older than kindergarten age, my mother said to me, “C’mon, we’re going to walk to Little Town.” Little Town was a little shopping center about three miles from our house in suburban Chicago. We walked down York Road, a busy two-lane highway, because my mom didn’t drive. So, we walked down York Road to a little shopping center, and before she went inside the store she said, “Wait outside for me here, I’m going to be a little while.” There was a hobby shop right across the street, so I went in the hobby shop while my mom went to this other store. When she came out, I met her, and as we walked home she burst into tears. This was the first time I’d ever seen my mother cry.

I didn’t know then why she was crying, but I learned several years later. At the time, my grandfather, my mom’s dad, was committed to the Cook County Sanitarium for tuberculosis. He didn’t have any insurance so my mom’s brother, my Uncle Frank, went to all the brothers and brothers-in-law — my mom had six brothers and three sisters — and asked each family for $200 to $300 to spring Grandpa out of the sanitarium. Well, my dad was a carpenter and my mom was a housewife and we had four kids, we had a 900 square foot home, we were very modest in our lifestyle. We didn’t have $200. I later found out that when my mom took me down to Little Town, the store she walked into was called Household Finance. You could get a little signature loan. My mom borrowed $200 and it scared the living hell out of her, and that’s why she burst into tears. The reason for the story is that money has always been a very highly emotional issue in my family. My family — my mom, my dad, my uncles and aunts — do not have any prosperity consciousness at all. They are blue-collar workers; they lived from check to check. Money was always frightening to them and a source of continual stress. I grew up in that environment, and I still have a little bit of York Road in me. And you know what? So does everybody else. So do all dentists, so do all team members. Money is one of the cultural things that we inherit from our parents. How we perceive money is one of the things we inherit from our family.

MD: Well, I remember once lecturing actually to a group of therapists — this was something that I was doing through a dentist friend — and I mentioned to one of the therapists about people having issues when they come to the dentist. And he said: “Well, we see people all day about all kinds of issues. What do you think is the biggest issue we see people for?” I said, “Probably related to marriage?” He said, “Yes.” And I said, “Probably sex?” And he said, “No, this one’s not even close to sex.” When I couldn’t guess what it was, he said: “Money. If you think people are messed up when it comes to their thinking about sex, wait till you get two people together in a marriage and you try to bring up money and what you should do with it.” He said everything else pales in comparison to how people struggle with how they feel about money.

PH: (laughs) Well, that doesn’t go away when they go into the dental office, does it?

MD: No, it doesn’t — it might even get worse.

PH: Sure, and it doesn’t go away when you go to dental school or the institute, or if you’re a dental hygienist or dental assistant. It follows us. But what are we going to do about it? Well, what we want to do is raise our Crossover Zone. Look at that chart, Mike (Fig. 2). I’ve got that person crossing over at $5,000. What do you think the impact on his practice would be if we could get him to cross over at $10,000?

MD: I think he would certainly diagnose more completely, more ideally, and really let the patient come to decide about the suitability — I’m speaking like you now, Paul (laughs). There are a lot of dentists I talk to who don’t like to diagnose more than two crowns at a time because they hate rejection. They end up doing the case piecemeal instead of getting the patient’s input. So obviously it would lead to an increase in production and collections in their practice, an increase in professional satisfaction, an increase in the strength of the team if they are getting bonuses on collections, and probably an increase in the satisfaction of patients.

PH: You bet. And put on top of all that an increase in the standard of care in that office. The cultural center being clinical quality is now well-served, isn’t it?

MD: Yes, it is.

PH: So this fringe item that we’ve been talking about, prosperity, has a direct and immediate impact on our cultural center. It cannot and should not be ignored. It is as important to clinical quality as is the quality of our impression material, the quality of the lab we use, the quality of the die stone, the quality of the alloy and our diagnosis. And yet dentistry still has its head in the sand when it comes to issues that are nonclinical, that are related to what impacts standard of care. If a dentist crosses over at $5,000, chances are this dentist is going to treatment plan a lot of cases that are in the $3,000 to $4,000 range and be successful with them. If the dentist then increases the Crossover Zone and crosses over at $10,000, he or she is going to do a lot of cases in the $7,000 to $9,000 range and do them pretty well, you know what I’m saying?

MD: Exactly, and you know it’s funny because it dawns on me that organized dentistry’s Crossover Zone is practice management, and that’s right where organized dentistry gets uncomfortable — because God forbid our members have a practice where they are happy and successful and can pursue clinical excellence without worrying about the balance in the checkbook on a month-to-month basis (laughs).

PH: Let’s put together a to-do list. Let’s get real dentist-oriented and put together a list of ways we can increase the Crossover Zone or how to decrease the Crossover Zone. What behaviors will increase it, and what behaviors will decrease it? Here are some good pointers on increasing the Crossover Zone. Really, at the heart of it is — an increase in the Crossover Zone means becoming more comfortable with higher fees and the dentist becoming conscious about protecting his or her confidence. Typically, what this means, Mike, is that the dentist needs to put themselves in collaboration with people who think abundantly. I belonged to an entrepreneurial group for 10 years — we met once a quarter. No one was a dentist. There were car dealers, restaurateurs, financial services people, attorneys, a wide range of people. And these were people who were building their business. Everyone thinks differently, and it’s great to be around people like that.

Find mentors, find someone who is doing what you want to do, and do what they’re doing. A big part of increasing your confidence, and protecting your confidence, is the issue that we were talking about at the beginning of this. First, you must protect your physical health — that is, if you’re overweight, if you lost vitality, if you’re not active, that has a depressive emotional effect on you. One of the ways to get a good start on increasing your Crossover Zone is to hang out with people who have high Crossover Zones and collaborate with them. Here’s a good way to decrease your Crossover Zone — watch a lot of daily news and TV. That is a great way to get depressed — I had to shut it off the other night. Check the stock market every day. Get in there and watch the fluctuation and just watch your blood pressure change. Stay isolated and don’t be collaborative and remain inactive. Those activities will cause a general depression and will actually shrink your Crossover Zone.

The second way to increase your Crossover Zone is to offer the patient a choice following your initial exam. We touched on this, Mike, in our article on left- and right-side patients (Chairside®, Volume 3, Issue 2). A choice dialogue is a dialogue that you’ll enter into following the exam. For example, a patient named Kevin comes in for a consultation and explains to you he’s got a dark front tooth, his daughter is getting married, and he’d like to get the dark front tooth improved. He also mentions that he wears a partial denture, although he’s not having a big problem with it right now — it just comes out in conversation. You do an exam, and tooth no. 7 has got a large mesial incisal composite; it’s been in there for 15 to 20 years, otherwise the tooth is healthy. However, his partial denture, the abutment teeth are mobile, he’s got periodontal disease, he’s got occlusal disease, he’s got loss of vertical dimension. Kevin’s case/ideal treatment plan would be a $27,000 treatment plan. Now, what do you do as a practitioner? Do you get into Kevin with a big treatment plan or do you get into Kevin by offering him something simple, to begin building a relationship? The recommendation I’m going to make here, as far as increasing the Crossover Zone, is that the initial examination be a short one, Mike. Instead of insisting that all new patients go through your complete examination process — which for those of us who have been to the institutes and are pursuing higher levels of dentistry includes study models, photographs, full-mouth radiographs, panoramic X-rays, oral cancer screening, a periodontal screening, occlusal analysis, DNA analysis, CAT scan — think about putting them through a simple initial exam. You can still do the oral cancer screening exam and the periodontal screening exam, but really focus on the condition that’s responsible for this guy not being happy with his teeth. And then once you see that condition and get a sense of his overall health, then offer the patient a choice relative to the therapeutic range. For example, after I did a simple initial examination on Kevin, I might say to Kevin something like: “Kevin, I can understand that you’re not happy with the appearance of this front tooth, especially with your daughter’s wedding coming up. Before we decide on anything, I want you to know that you have a choice today: we can focus on getting you to look good for the wedding or, in addition to that, would today be a good time for us to look at all your teeth and perhaps plan for a lifetime of good dental health? Which would be better for you today?” Now, that’s a choice dialogue, Mike. And what that does — it allows you to understand what the patient is ready for. When you understand what the patient is ready for, and then deliver it, it increases their confidence in this relationship.

Now, when I teach this choice dialogue, I get some pushback from practitioners who say, “Yes, but if you just offer them simple care, if you just fix that front tooth, then you’re going to miss out on the opportunity to completely treatment plan their mouth and provide complete dentistry.” And at that point, they give me a lecture about how they pride themselves on practicing comprehensive dentistry and recommending comprehensive care to all their patients. Well, I don’t see where that is such a badge of honor. I want you to think about the advantages of a patient like Kevin. Let’s say you have a patient like Kevin who has a potential full-mouth reconstruction. What are the advantages of doing something simply on him first? Number one, if I’m going to fix just one tooth on him, Kevin is going to experience my touch, my hands. Kevin is going to experience the fact that I’m a good listener, that I’ve given him a choice. He is going to experience my office, my team, my punctuality, my process, etc. Kevin is going to see an outcome — a tangible outcome very early in our relationship. He’s going to become a happy guy, and there’s tremendous advantage to that because it builds confidence on the patient’s part towards us.

MD: It’s like test-driving a car before buying it. Who buys a car without getting the opportunity to test-drive it? The patient wants to test-drive you, his dentist.

PH: Absolutely true. So the myth is, let’s do complete exams on everyone and that way we can showcase our comprehensiveness and thoroughness and how much we care. I don’t take that point-of-view at all. My point-of-view is to showcase what you can do in the mouth. When you do, and can make a patient happy, that sends a much stronger message of value than any examination you could ever do. Kevin is much happier walking out with a shiny front tooth that matches his other teeth, as opposed to the complete examination process. He gets more value out of having something simple done initially. That right there will inspire the patient’s confidence in you and then you will be more confident as a practitioner, which increases your Crossover Zone. Does that make sense, Mike?

MD: Absolutely, it does.

PH: The way to decrease your Crossover Zone is to insist that all new patients go through complete examinations. It is impossible to build a relationship with a patient through a procedure they don’t want.

MD: Especially because the culture of clinical excellence states that the patient will be impressed by the fact it is the most thorough examination they’ve ever had, where in reality their anger level may just be rising higher and higher because this is not what they had in mind.

PH: Right. And when you look at the concept of examination, there’s really two examinations going on at the initial appointment. There’s the one that we do, but there’s another one going on — it’s the one that the patient’s doing. I think it’s much more important that we pass their examination than submit them to ours. I can make that patient satisfied and give that patient a sense of value. And then, I have earned the right to influence that patient another day.

When I average Crossover Zones’ from the teams — and this is again a decade of empiricism, a decade of doing this and averaging the number from literally hundreds of practices — most teams cross over between $6,000 to $6,500. I don’t know why that is, Mike.

MD: Right, because the patient is the only one in this relationship with the ability to decide whether or not any of this is going to happen. We can’t force it on them. They really are the ones interviewing us and making a decision whether or not this relationship is going to move forward.

PH: Exactly right. The second way to increase the Crossover Zone is to get really clear about what’s going on with the patient’s life as far as their life circumstances. I call it understanding the patient’s fit issues. Fit issues are those life circumstances that include their budget and their life and their time and their hobbies — it’s all of the contemporary life events that are going on in people’s lives. Mike, right now in my life, my fiancée and I are buying a house down the street here. It’s springtime now, we just put the boat in the water. I got stereo speakers I’m working on one side, my exhaust gas sensors weren’t working, I had a tear in my part of the vinyl that covers the windshield. I’ve got my television studio. I’m doing work with you. I have a lot of complexity in my life right now. And it would be very difficult to carve out three to five hours every other week to have my mouth reconstructed right now — it would be a tough thing. And the more we can understand the life circumstances of our patients, understand these fit issues, the better we can enter into a dialogue about those issues.

Again, Mike, we touched on this last time. I called it an advocacy position or advocacy dialogue. That is, I’ve got a patient in this chair. Let’s say this guy is Kevin again. I fixed Kevin’s front tooth and he is happy. I say to him: “Kevin, listen, enjoy the wedding. However, I want you to come back here and let me take a real good look at your mouth. The reason I’m saying that, Kevin, is that while I was fixing your front tooth, I noticed that you have other conditions in your mouth that we really can’t ignore. I noticed some teeth that move, I noticed some gum infection, I noticed that your bite isn’t quite right. And it’s my responsibility as a dentist to let you know these things. You’re not obliged to treat anything right now, but I’m really bound by good dentistry and dental ethics to make sure you understand that. Kevin, I’d really appreciate it if you’d come back and let me do a complete examination so you understand what your needs are.”

If a dentist crosses over at $5,000, chances are this dentist is going to treatment plan a lot of cases that are in the $3,000 to $4,000 range and be successful with them. If the dentist then increases the Crossover Zone and crosses over at $10,000, he or she is going to do a lot of cases in the $7,000 to $9,000 range and do them pretty well.

So, Mike, it’s really important for the reader to know that I’m not just treating some chief complaint and then ignoring the patient. I’m treating the chief complaint, I’m making them happy, I’m building my confidence, they’re building their confidence, but now I’m asking the patient to return. And prior to that complete examination, I’m going to engage the patient in a conversation about what’s going on in their life, and I’m going to understand. I’m going to find out about that new house they’re buying, about that boat. Why? Because it’s called a conversation. That’s not in the culture of dentistry. That’s another thing that we need to have — stronger verbal and conversational skills. Learning how to bring dialogue out of a person, how to get another person to tell you a story about their life. It’s within these dialogues that we’ll understand what the patient’s fit issues are. When we understand the fit issue, Mike, it’s absolutely key in increasing the Crossover Zone. Why? Because it gives me the confidence to quote fees that may be beyond my Crossover Zone. When I understand the fit issue, I can integrate it into my treatment plan with the patient. For example, let’s say Kevin’s treatment plan is $20,000 and I’m crossing over at $10,000. But I understand Kevin has two boys in college and is remodeling his house. Now, when I present care to Kevin, I want to present the fit issue along with the treatment plan. I’m going to say something like this: “Kevin, first of all, I understand that you have two boys in college right now, that you’re really proud of that, you’re spending a lot of time visiting them. I also know that you’re remodeling your home and I just remodeled a part of mine, and I know all about that process. I want you to know that we can help you with your care. What I’m not sure is how that fits into your life right now. Do we do your care right now or later? Or a little bit at a time?” You see, what I’m doing here is I’m not allowing that patient’s fit issues to get in the way emotionally with me. What I’m doing is almost subordinating my treatment plan to what this patient has going on in their life. What that does for me is increase my Crossover Zone because I’m telling this patient when you’re ready, we’ll be here — it’s very authentic and it’s based on my understanding of that patient’s fit issue.

MD: Interesting. I can also picture a scenario where a young dentist right out of school might have a pretty low Crossover Zone, like $1,500, whereas a 60-year-old patient who owns his own business might actually have a higher Crossover Zone, where anything under $4,000 they just kind of sneeze at.

PH: Well, I think you’re correct there, Mike. I think patients have Crossover Zones. We all kind of have an idea or intrinsic value of what we’re willing to pay for something. We’re getting estimates right now on painting the inside of the house. And you know, I looked at the house — there are four bedrooms, a big rec room, a porch, kitchen and a dining room — and I’m thinking, “What is it going to take to paint this place?” It seems like it should be about $5,000 or $6,000 to paint the whole place. So I walk in with an expectation rattling around in my head. I have a Crossover Zone related to cars. I don’t want to spend more than $60,000 on a car, I just don’t put the value there. I’d rather put it in the boat … you know what I’m saying?

MD: That’s different in the sense that you know what the car is going to cost before you get to the lot. I mean you don’t know it to the exact penny, but when you have somebody over to get an estimate on painting and you’re thinking it’s going to be $4,000 or $5,000 and they throw out a number like $12,000, there’s an opportunity for you to be stunned, right?

PH: Right. Sure. You know, the Crossover Zone is largely caused, but not completely caused, by the dentist who typically doesn’t know how to respond when the patient says, “No, I can’t afford it,” or “Gosh, I had no idea it would be that expensive.” I mean, would there be a Crossover Zone, Mike, if we knew the patient would say yes?

MD: No, not at all! If we knew the patient would say yes, we’d probably have to double the number of dentists because everybody would be doing the ideal treatment and only be able to see about a third of patients currently in their practice.

PH: Sure. So, if there’s no Crossover Zone, if we knew the patient would say yes, then it’s not about the money. It’s about the patient’s negative reaction to the money … you see that? If we know the patient is going to say yes — that is, if you quote $10,000 and they say, “Yippee! When can we start?” — there is no Crossover Zone. But what if you had fear of the patient screaming when you say $10,000, demanding to know, “What makes it so expensive?” The dentist doesn’t have the answer to that question, which is what creates a lot of anxiety and results in a low Crossover Zone. So, it’s more so about the dentist’s feeling than it is about the patient’s feeling.

MD: Absolutely, and it’s about the dentist’s confrontational tolerance and not wanting to be rejected. It really almost goes back to the dentist’s reason for becoming a dentist—so that he or she didn’t have to go into sales.

PH: (laughs) Right, right! So the whole issue of advocacy — that is, understanding the patient’s life circumstances and then asking the patient whether the treatment plan fits the life circumstances now or later or a little bit over time — really helps ease the anxiety of the Crossover Zone. A way to decrease the Crossover Zone is just continue to pursue excellence. It’s the whole blind pursuit of saying: “Listen, I’m going to give you the best treatment plan. Whether you’re my brother or my mother or my wife, this is what I would do. And this is the very best, and we use the best this, and we have the best lab…” It’s that head-in-the-sand way that will continuously drive the Crossover Zone down, because treatment planning and offering care in the absence of knowing the patient’s fit is always an invitation for stress on you and your patients.

MD: Now, when you have that staff meeting and you find out what everybody’s Crossover Zone is, if you happen to have one employee who is at $23,000, does she immediately become your financial coordinator?

PH: Well, I’d certainly think about it. It’s like a basketball game. If the game is tied and there’s three seconds on the clock, who’s going to take the final shot? Your best shooter, right? It’s the same thing in the dental practice. You find out who is really comfortable talking about money. And you know what? It may not be your treatment plan coordinator. If my treatment coordinator is crossing over at $1,200, I’m going to have to re-purpose her, find another place for her in the practice, replace her. But it becomes extremely critical that the person who is doing the treatment planning, or doing financial arrangements, has an extremely high Crossover Zone. Diagnostically, you can’t live without knowing that.

MD: Agreed.

PH: Another major aspect of the Crossover Zone is what goes on in the dental hygiene room. And this might be the most important thing of all that we talk about here. Most practices are filled with complex care patients who have not completed their treatment. They might have gotten part of their treatment done, but there are a lot of practices with many patients who have literally millions of dollars worth of dentistry to be done in their mouth. And every six months, the hygienist revisits with those patients on an ideal basis. Now, what are the hygienists saying? Well, the patient needs some crown and bridge, right? And the typical — again, I’m not trying to beat up the hygienist here, I’m just telling you what I know to be true — patient needs some crown and bridge, patient comes in for six-month recall, and the hygienist says, “Are you ready for the crown and bridge work?” Patient says no. Six months later, “Are you ready for the crown and bridge work?” Patient says no. Six months later, “Are you ready for your crown and bridge work?” Patient says no. Six months later, patient says, “Don’t mention the crown and bridge work!” Six months later, broken appointment. Compound that with courses dentists can send their hygienists to that teach them how to sell dentistry out of dental hygiene. I think the dental hygienists are kind of caught in the middle between the patient and the doctor they work for. And dental hygienists oftentimes have extremely low Crossover Zones relative to complete care dentistry.

So, what can a dental hygienist do to increase her Crossover Zone? How can she become more comfortable talking about money? This is a major issue in most offices, Mike. When the dentist offers care to a patient and the patient is not ready for that care, it’s really important that the dentist understands the fit issue behind why the dentistry is not appropriate this time. This goes back to the previous point that I made about understanding the patient’s life circumstances. If I recommend to Kevin full-mouth dentistry, I understand he has boys in college. He tells me he’d like to get work done but he has to wait because the kids are in college. That fit issue is then documented in Kevin’s patient record. And six months later when Kevin comes back in, the hygienist should revisit the fit issue before she revisits the condition. So Kevin comes in, sits in the chair, and the hygienist asks: “Any changes in your medical history? Any changes in your dental history?” “Nope.” “Kevin, how are the boys doing at school? Are they still there? Tell me what they’re up to.” What we’re going to do is revisit the fit issue. Then after I revisit the fit issue, I’m going to reflect back on it. “Kevin, considering your boys are still in college, is this a good time for us to revisit the recommendations that Dr. Homoly made for you last time?” Do you see how that works? You’re asking the patient, “Is now a good time?” That is testing readiness, Mike. That is something you and I have talked about in all three articles we’ve done. The hygienist tests for readiness, and she doesn’t feel out on the limb as far as recommending an expensive treatment plan the patient can’t afford — which makes hygienists feel uncomfortable or embarrassed. So, the hygienist revisits the fit issue before she revisits the condition. And listen to what I’m saying carefully here: I’m not saying that she shouldn’t revisit the condition, but rather that she should revisit the fit issue prior to revisiting the condition. The other side of that would be just to put the patient in the chair and educate the hell out of them based on their conditions. And that oftentimes ends up with the patient being educated right out of the practice.

MD: Yes, because you did the same thing to them last time with no regards for suitability. They are probably willing to accept it once, that you’re going to do that, but if you go in there again and try to do that without taking into account their suitability and their life circumstances, then yeah, at some point, it’s that whole thing about don’t try to teach a pig to sing. You keep reminding them they don’t have any money.

PH: Right. After a while it just feels like nagging. Overeducating the patient, relying too highly on patient education on a patient who isn’t ready, feels like sales pressure. And that’s how you lose them. Last point here about the Crossover Zone, Mike; let’s start with the dentist. The dentist needs to get his own financial house in order. That means meeting with a financial planner who can get the demons out of the dentist’s life relative to money. If there are back taxes due, if there is no savings, if there are labs sending cases COD because you’re three months late on your lab bill — all of that has a huge depressive effect on the Crossover Zone. Oftentimes, dentists end up treatment planning patients based on their own ability to pay, not on the patient’s ability to pay. My recommendation — and it might be that maybe this is the first recommendation that a dentist should do — is to get a financial services specialist, and take your own medicine as far as how we treat patients comprehensively. Get a comprehensive examination and diagnosis and treatment plan of your own financial health, and build it into the culture of your family and your team. If you have team members who are struggling financially, team members who are involved in financial issues that are toxic to their mental health, it’s not unthinkable for them to get help also; that can be a huge benefit of working for you. It could be a huge tool for you to build long-term loyalty with staff. And maybe you hire a financial planner to come in and to work with different team members as far as getting their credit cards figured out or restructuring their debt, or one of a hundred things that financial planners can do to ease some of the demons flowing related to money.

I believe that the concept of prosperity needs to be a companion cultural icon right next to clinical quality, because prosperity and clinical quality are joined at the hip, Mike. When a dentist is prosperous and profitable, then that dentist can afford a good facility, pay great wages, hire great people, afford the finest materials, get good equipment, use the best laboratories, can afford to take time off for rejuvenation — and all of that has a dramatic and immediate impact on the clinical quality. The topic of prosperity should not be on the fringe, but it should be at the center of what we do in our continuing education efforts in dentistry.

The myth is, let’s do complete exams on everyone and that way we can showcase our comprehensiveness and thoroughness and how much we care.

MD: Wow, that’s a nice wrap-up right there. And that certainly is again against the grain, because, it’s as we’ve mentioned before — the dental community is so ingrained with nothing but clinical excellence as the end-all, be-all to a happy career. And I think you’ve laid out a pretty good case today for why that’s not necessarily true. And this leads us into a good fee discussion for next time. You’ve suggested before that while a crown fee of $900, for example, works really well for one, two or three crowns, it does not work beyond three crowns. I know that’s going to be a great interview and a great topic for discussion. Thanks again, Paul!

PH: It was my pleasure, Mike.

To contact Dr. Paul Homoly or to purchase his book “Making It Easy for Patients to Say ‘Yes,’” call 800-294-9370, visit paulhomoly.com or email paul@paulhomoly.com.

CEREC is a registered trademark of Sirona Dental Systems, Inc. (Charlotte, N.C.).