Upgrading Porcelain Veneer Restorations: A Case Report

Introduction

Placement of indirect labial veneers (porcelain or composite) continues to be an excellent option to correct many esthetic complaints that our patients have with their smiles. Some of the more common indications for their clinical use include:

- Minor corrections of anterior tooth morphology and emergence angles to fill in spaces in the gingival embrasure areas when these spaces are an esthetic concern for the patient.

- Minor corrections in tooth position (rotation, labio-lingual arch position and crowding) if orthodontics is either not indicated or not accepted as a treatment option by the patient.

- Diastema closures and corrections of anterior tooth proportion (golden proportion).

- Establishment of anterior guidance and canine disclusion in patients where preparation for full-coverage restorations would necessitate unnecessary removal of healthy tooth structure.

- Improving tooth color for a patient where tooth whitening was not a treatment option or did not yield a satisfactory result for the patient.

Tooth Preparation

The amount of tooth reduction required depends on the specific clinical situation. In general, 0.5 to 0.7 mm of tooth reduction is needed. In some cases, where “nature” has done the tooth preparation or natural tooth contours are less prominent, “no prep” options are also possible. If changes in tooth position are required, some areas of the tooth may be prepared more, others less.

It is recommended to first contour the teeth to their ideal position using a cylindrical diamond, then use depth cutters to remove a uniform amount of tooth structure to compensate for the thickness of the restoration. In extreme situations in which the dental pulp is encroached upon, root canal therapy is recommended rather than overcontouring the restoration. In cases where a low value (dark) preoperative tooth color is to be changed to a high value (light) color, more tooth structure may need to be removed (1.0 to 1.5 mm) to create enough space for opacious dentin or opaquers to block out the darkness. For some patients, preoperative tooth whitening may be indicated to increase the value of the underlying tooth structure, allowing for less tooth structure to be removed during the preparation process.

Gingival margins should be placed at the gingival crest or slightly above. The interproximal margins should be carried into the lingual portion of the contact area. If diastemata are present, the interproximal margin of the preparation should be carried lingually to the linguo-proximal line angle. Also, when closing spaces, it is important to prepare the gingival margins far enough into the proximal areas so that the restoration margins are not visible from a three-quarter or oblique view (when the patient turns their head to the side).

After the preparations are finished, it is recommended to use a fine cylinder finishing diamond to make the preparations as smooth as possible. Aluminum oxide strips can be used to smooth and polish interproximal surfaces without compromising the proximal contact.

Impressions

As the gingival margin of most veneers will be slightly above the gingival crest, a very thin retraction cord, such as a #00 or #000, can be placed in the sulcus and left in place during the impression process. If a particular case requires subgingival margins, a #1 retraction cord is placed over the #00 or #000. When taking the impression, pull the #1 cord and leave the #00 or #000 in place. This “double-cord” technique will produce flawless intracrevicular impressions time after time.

There is also a technique that can be used that will allow for an “anesthesia-free” and “retraction cord-free” procedure. First, a stock tray is selected to fit the patient’s maxillary arch form. Next, a heavy-bodied tray material is injected into the tray and placed in the patient’s mouth. This will convert the “stock tray” to a “custom tray” filled with set heavy-bodied impression material.

The next step will be to wash with a light-bodied material, but a very important technique difference from a traditional “putty-wash” technique is used. When most clinicians perform a wash of a heavy-bodied impression, the papillae between the tooth indentations are removed and the space is completely filled with light-bodied wash material and reseated in the patient’s mouth. It is very difficult to displace the large amount of light-bodied material when seating the tray, and a less-than-desirable end result ensues from an incomplete seating of the tray. The difference here is the amount of light-bodied material that is used. It is very important to inject only a small amount of light-bodied material around the periphery of the tooth indentations in the heavy-bodied material. The heavy-bodied material will then force the light-bodied material into the intracrevicular spaces around the teeth. The smaller amount of light-bodied material allows the operator to more accurately seat the impression and gain sufficient “retraction” to force the light-bodied material into the crevices.

Pull the #1 cord and leave the #00 or #000 in place. This “double-cord” technique will produce flawless intracrevicular impressions.

Provisionalization

A fast and simple technique to fabricate provisional veneers utilizes a preoperative wax-up as a template. Create a plastic provisional stent of the corrected tooth positions using a vacuum former and .040 plastic materials. After tooth preparation and final impressions, fill the stent with a bis-acrylic provisional material and place over the teeth for two minutes. The patient can close in centric occlusion over the stent material during this time. After initial setting of the bis-acrylic material, it can be removed from the stent and contoured with abrasive discs and fine laboratory acrylic carbide burs.

Any repair or addition to the provisional restoration is accomplished using flowable composite material and light-curing, either at the lab bench or intraorally while the provisional restoration is in place on the preparations. It is not necessary to use bonding agents prior to the addition of the flowable resin if the surface is first roughened to create micromechanical retention. Also, the secret to successful addition of flowable resin to bis-acrylic provisional restorations is to create a long bevel on the bis-acrylic material, add the flowable resin to the repair area and continue to “feather” the flowable composite over the beveled surface of the bis-acrylic 3 to 4 mm beyond the repair area. Finally, finish with abrasive discs to original tooth contour for a seamless repair.

Cementation

Placement of porcelain veneers can be accomplished using dual-cured or light-cured resin cements. The veneers are first tried on individually to check margins, then collectively to evaluate contact and esthetics. A drop of water on the inside of the veneers can help to hold them in place for evaluation by the doctor and the patient. For most cases, transparent or clear resin cement will be the cement of choice.

There are some clinicians who report a color change with time when using dual-cure tinted cements. It is the opinion of this author that color change in older veneer cases occurs because of color change in the tooth, not in the 10-micron layer of cement between the porcelain and the tooth.

The reason dual-cured cements are selected by some clinicians is because of the ease of the cleanup process. These types of cements will reach a “gel phase” about two minutes after mixing. At that time, the operator can use an explorer or fine curette to remove cement excess prior to light-curing. Dental floss can also be passed through the interproximal areas to be sure they are free of cement. While performing the cement cleanup during the gel phase, the dental assistant stabilizes the restoration using finger pressure. Once the excess resin cement is removed, the restorations are light-cured. Using this technique will minimize any rotary finishing, and polishing should also be kept to a minimum. Light-cured cements can be used successfully if the operator has a tacking tip on the curing light and selectively “tacks” the center of the restoration on the tooth while leaving the cement at the margins uncured. The marginal excess is then removed with a brush and floss is used to clear the interproximal areas while stabilizing the restoration. A total cure is done once the cleanup is complete.

As previously mentioned, some clinicians and researchers believe that dual-cure resin cements change color over time and affect the visual shade of the restoration. This may be true in the lab, but is this really happening clinically? If one takes a clear shade of resin cement and an A3 shade, places a drop of each on a glass slide, and squeezes another slide on top of the cements to simulate a restorative interface, an interesting thing occurs. It is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish between the two colors because the cement layer is so thin. How much color can be squeezed into a 10-micron layer of cement? How does that “change” become visible behind an opacious layer of dentin porcelain followed by body porcelain? The “contact lens” effect does allow the color of the tooth to affect the final shade of a restoration if the ceramist does not lay down an opacious material first or if the restorative gap is too large so that the cement layer is too thick.1,2,3,4,5

Color change in older veneer cases occurs because of color change in the tooth.

Case Report

Placement of the Initial Porcelain Veneer Restorations

In 2002, my wife Michele expressed a desire to have porcelain veneers placed to enhance the esthetics of her smile. She presented with a Class I occlusion and had very thin, opalescent enamel that did not respond well to tooth whitening (Figs. 1–3). Her desire was to have a “brighter, more youthful-looking smile.”

Following the methodology described above, the teeth were prepared using a minimal preparation technique (Fig. 4), master-impressed and then provisionalized using bis-acrylic provisional material. A bleached white color of feldspathic porcelain was chosen, and the restorations were fabricated and finally cemented with a clear, dual-cured resin cement. Figures 5–7 show Michele’s retracted full-arch, postoperative full-smile and full-face views, respectively. Michele was thrilled with her new smile makeover!

Seven Years Later

Michele had never specifically commented that she noticed her veneers were not as bright as they were when placed because there was such a gradual change over time (Figs. 8–10). Compare the post-cementation photo, Figure 5, and the seven-year postoperative photo, Figure 9. A significant color shift is very noticeable when performing a direct comparison of these photographs. Being surrounded by the dental field, Michele was also aware that newer porcelains were being developed that were brighter in value than those that were available when her initial esthetic restorations were fabricated. She therefore expressed a desire to have her veneers redone.

Although a color change was observed (Fig. 11), from a purely dental perspective, the initial restorations were still very serviceable, with no signs of fracture, wear or marginal breakdown. Knowing that conventional removal of these veneers with rotary instrumentation would result in removal of more healthy tooth structure, the dilemma was whether to intervene and replace the veneers, or wait until the restorations broke down and required replacement. As with most patients, Michele was not concerned with the potential loss of 0.1 to 0.2 mm of tooth structure — she wanted brighter porcelain veneers!

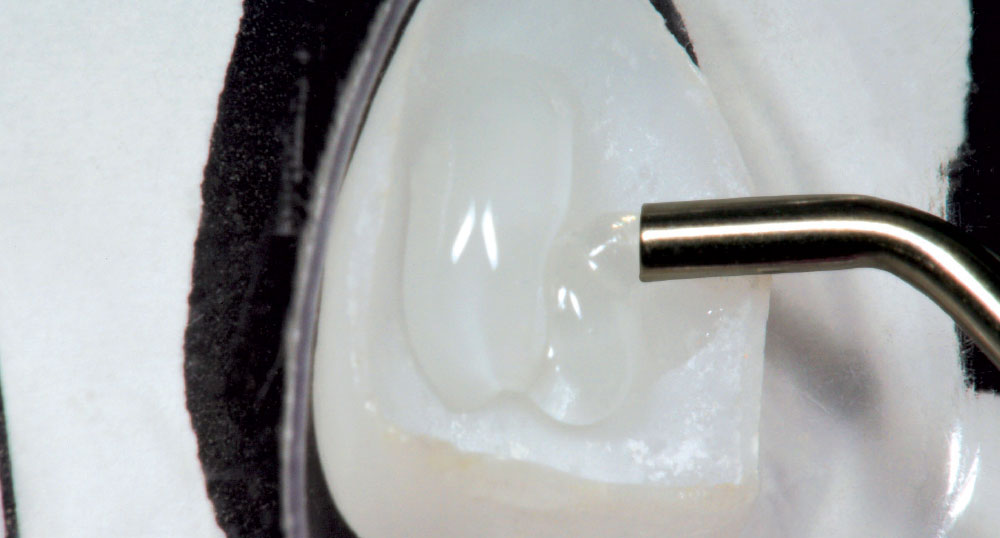

It was decided to grant her request and upgrade her esthetic restorations. During this period of time, as an all-tissue laser user, it was discovered that the laser could be used to conservatively remove porcelain veneer restorations without further loss of tooth structure. It is believed that because the laser wavelength of the Er,Cr:YSGG laser seeks water, the resin cement is denatured and expands, causing the veneer to fracture and separate from the tooth. The veneer can then be easily removed using a scaler (Fig. 12). Michele had 10 porcelain veneers on her maxillary arch, all of which were completely removed with the laser in less than 10 minutes! The cement layer remained visible on the preparation surface (Fig. 13). Next, an Enhance® point, a composite polishing point (DENTSPLY Caulk/DENTSPLY International; York, Penn.), was used to remove the cement from the preparation. Air abrasion can be used for this as well. After minor marginal adjustment of the preparations to compensate for a small amount of gingival recession on the mid-facial of some of the preparations (Fig. 14), a retraction cord was placed (Fig. 15), a new master impression was made and bis-acrylic provisional restorations were placed (Fig. 16).

The ceramist then fabricated the newer, high-value porcelain veneers. Figure 17 shows the finished central incisor restorations. A new light-cured cement (Kleer-Veneer™ [Pulpdent Corporation; Watertown, Mass.]) was used to cement the newly fabricated porcelain veneer restorations (Figs. 18, 19). Note that this veneer cement is totally transparent, unlike many other “untinted” resin cements on the market. It is the author’s opinion that this type of cement is particularly useful for very thin “no prep” veneers when blocking out tooth color is not required.

At a subsequent visit, the process was completed on the mandibular arch. Figure 20 shows the mandibular veneers being removed with the Waterlase MD™ (Biolase Technology; Irvine, Calif.). The completed porcelain veneer esthetic upgrade can be viewed in Figures 21–24. Note that clear porcelain was used at the gingival margins to gradually blend the root color at the restorative interface and make the margin less apparent.

Conclusion

“Wants-based” dentistry, especially that which is purely esthetic in nature, is often on a different timetable than conventional restorative or rehabilitative dentistry. Its “useful life” is not determined necessarily by marginal or occlusal breakdown, but by what the patient sees in the mirror. For some dentists, it is hard philosophically to remove and replace “serviceable” dental restorations. However, in this day of elective dentistry, we must realize that replacement of existing restorations can now be determined on esthetics alone … and this, at any moment, is done at the sole discretion of the “wearer.” In the author’s case: “Happy wife, happy life!”

Dr. Robert Lowe is in private practice in Charlotte, North Carolina. He also lectures internationally and publishes on esthetic and restorative dentistry. Contact him at boblowedds@aol.com or 704-364-4711.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to acknowledge the artistic expertise of Vincent Devaud, CFC, MDT, of Vincent Devaud Dental Laboratory, Pasadena, California, for his work on this case.

References

- ^Strassler HE. Minimally invasive porcelain veneers: indications for a conservative esthetic dentistry treatment modality. Gen Dent. 2007 Nov;55(7):686-94; quiz 695-6, 712.

- ^Malcmacher L. No-preparation porcelain veneers–back to the future! Dent Today. 2005 Mar;24(3):86, 88, 90-1.

- ^Etman MK, Woolford MJ. Three-year clinical evaluation of two ceramic crown systems: a preliminary study. J Prosthet Dent. 2010 Feb;103(2):80-90.

- ^Guess PC, Strub JR, Steinhart N, Wolkewitz M, Stappert CF. All-ceramic partial coverage restorations–midterm results of a 5-year prospective clinical splitmouth study. J Dent. 2009 Aug;37(8):627-37.

- ^Lowe RA. Shade Instability: Examine a Root Cause of Mismatched Ceramic Restorations, Dental Products Report, 2008 Sep:116-22.

Reprinted by permission of Oral Health, April 2011