Laboratory Portrait: Mikhail Tkachev – Engineer, Research and Development, Glidewell Laboratories

article by Al Lefcourt photos by Ed Pelissier and Kevin Keithley

It must have been something about that visit from the Soviet secret police. Even his top-secret military clearance couldn’t keep Mikhail Tkachev from coming under suspicion for the simple act of requesting permission to visit his friend in Poland, and when the men in black suits came to interrogate him at his Vladikovkas apartment, he knew it was time to take leave of his Mother Russia.

It was a country Mikhail knew well, perhaps too well, having been the second of eight children born to a father who moved 13 times, by Mikhail’s count, before he was old enough to join the army. There he was first assigned to a tank unit, but his aptitude with electronics recommended him to special duty building top-secret devices in a Soviet weapons lab. He soon learned to reverse engineer, repair and improve any electronic device in the world, a skill that would ironically be put to a positive use, at last, years later at Glidewell Laboratories.

That journey, from a small town just 15 miles from the now war-torn Chechnya to Orange County, California, is truly the stuff of Hollywood films.

It took two years from that fateful visit from the secret police, and two major upheavals in the Russian government, for Mikhail’s desire to emigrate to the U.S. to come to fruition. Now, in 1991, a married man with a three-year-old daughter and a six-year-old son, he jumped at the opportunity offered by Mikhail Gorbachev’s bold open-border policy. Mikhail Tkachev (pronounced T’Kah-chow) brought his family to the U.S. with no money and no English, bearing only the phone number of a friend in Sacramento whose simple promise of assistance was enough hope for someone seeking a new start in a land of freedom.

But something went awry the moment he and his family set foot in the promised land. A clerical error at the immigration office in the airport in New York rerouted them to St. Louis, Missouri, instead of to Sacramento where their friend awaited. There they were placed in a boarding house in a rough section of St, Louis, a town where they knew no one and, indeed, weren’t even quite sure where they were. But a couple of noisy nights marked by the sounds of nearby fights and robberies quickly told them it was a place they didn’t want to be.

Amazingly, Mikhail found someone who spoke enough Russian to help him get in touch with his Sacramento friend, Victor. Victor had driven to the Los Angeles airport to pick up the Tkachev family only to be left there helplessly wondering what had happened to them when their plane landed and they weren’t on it. On receiving the call from his stranded Russian friends, Victor was stunned by what had happened to them, but having preceded the Tkachevs to America by only three months, he hadn’t enough money to fly them to California.

Mikhail, ever resourceful, went through his little black book of phone numbers he’d been collecting all though his immigration process, and called a friend of his brother’s, also from the Russian military and now in the U.S., and he immediately agreed to loan them some travel money. But the money was just enough to get them to Los Angeles; someone would still have to drive down to pick them up.

But again fate had other plans. Mikhail’s son, Sergei, got ill on the flight to LA, causing the plane to land in Phoenix. There the airport medical emergency team flew into a panic; they spoke no Russian, the Tkachevs spoke no English, and they had on their hands a little boy turning bluer every minute. They called over the airport PA system for anyone who spoke Russian, and only one person stepped forward: another boy, a brave little fourth grader who was just beginning to study Russian.

Language turned out to be just one barrier they faced. Mikhail had no knowledge of the American systems of health care, insurance and credit, and the fourth-grader’s language skills were clearly not up to the task of explaining it all. Thinking he would have to pay cash for the hospital cash he didn’t have, Mikhail made a difficult decision. He waited a bit for his son to feel better and asked to resume the flight.

At this point, of course, the airline was concerned about liability for the sick child and made the Tkachevs sign a medical release form they really didn’t understand. But for them, it was California or bust, so they were happy just to finally arrive at LAX.

Where yet another disappointment awaited. Their friend Victor’s car had broken down on the way from Sacramento to Los Angeles, and this time it was the Tkachevs who were left alone and wondering at the airport.

Mikhail again pulled out his little black book and found a phone number with a Russian name but no record of who it was or where the number had come from. But, it was a local number and he called it. It turned out to be a generous and helpful fellow named Peter who’d lived in the U.S. since the age of three but who spoke fluent Russian. They asked Peter only for help in contacting Victor, but ties to Russia and the Tkachevs’ absurd predicament opened Peter’s heart to house them for two weeks, then bring them to a place they could rent, and even to loan them enough money to get them started in their new home.

And as unlikely a series of events as this might be, it turned out to be nothing short of miraculous for Glidewell Laboratories. If Mikhail had managed to get to Sacramento on either of his attempts, he may not have settled in Los Angeles and may have never brought his considerable talents to the company. And that would certainly have been a loss not just for Glidewell, but for the dental industry at large.

Mikhail’s first job in America was one of the few things one could do where the boss had only to point and motion for you to understand what was expected of you: breaking rocks with a sledgehammer at construction sites. Not the place one would normally expect to find a man with a degree in electrical engineering. Unwilling to accept a long-term career in rock breakage, Mikhail enrolled in English classes so he could better his lot.

The teacher was demanding, but hardly as demanding as Mikhail was of himself. He worked and he schooled, both full-time, determined to get ahead in America. But he wasn’t earning enough to support his family and his debts, so he started dental technician classes at Pasadena City College (7 a.m. to 5 p.m., Mon.-Fri.!) and, on the side, taking in auto transmissions for repair. It was something he could do, and do well, for much less than a repair shop would charge, because he didn’t have the overhead of a garage. Which also meant…he didn’t have a garage overhead.

So Mikhail rented workspace when he could, but often he actually had to carry transmission up the stairs to his apartment to tear them apart and rebuild them. A grueling task he did for five years while he continued to perfect his English and his dental tech skills, and he now bears the back pain to prove it.

As with everything Mikhail undertakes, he was so good at it, his customers nearly prevented him from quitting when he was offered a job as an R&D dental technician at Glidewell Laboratories. But he eventually was able to devote himself full-time to Glidewell, where his new English skills and his old Russian military engineering training combined to make him an integral part of one of the dental lab industry’s most advanced commercial R&D departments.

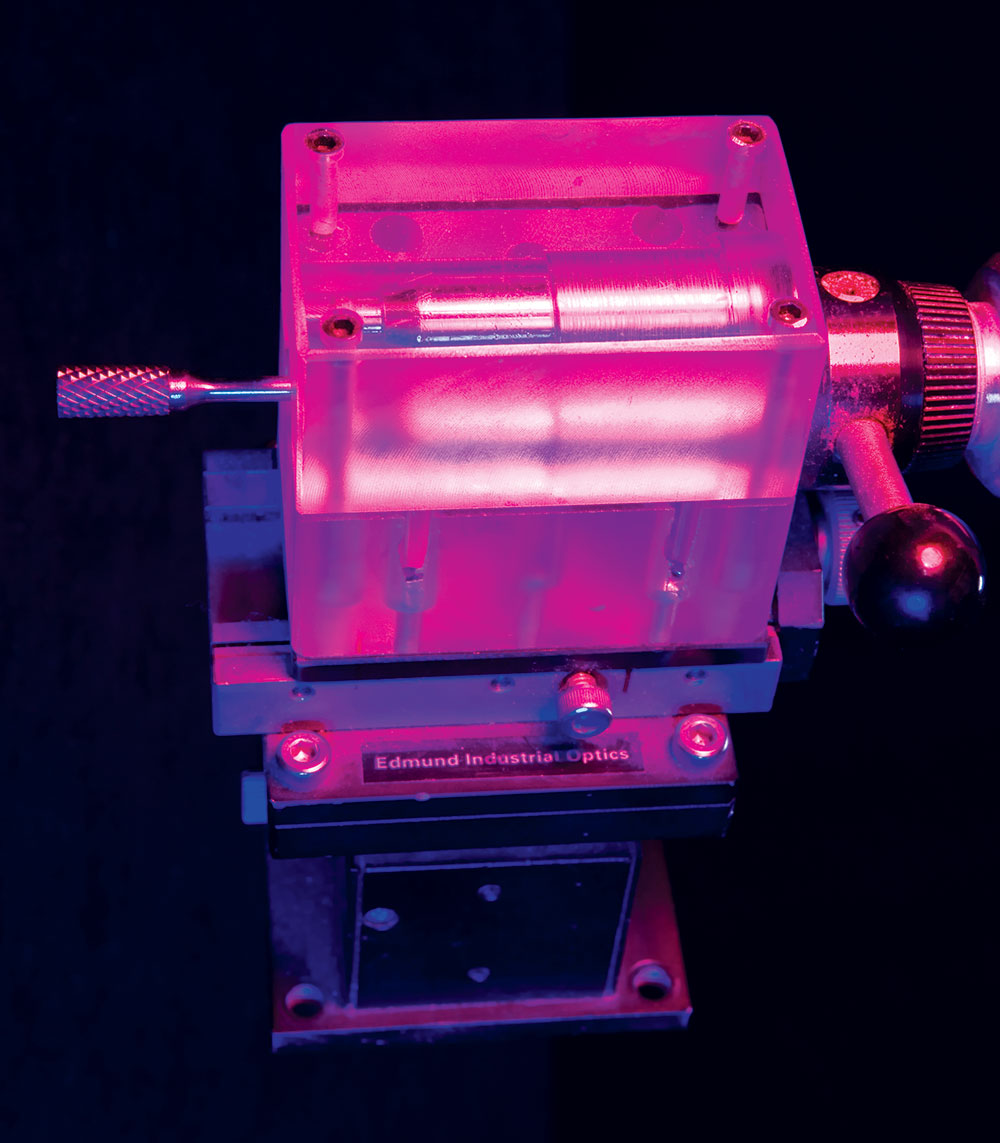

One of the first episodes that brought Mikhail’s talents to Jim Glidewell’s personal attention was the failure of a critical $30,000 piece of intricate equipment from Germany that would have slowed production of restorations to a crawl, something that would have been unacceptable to Glidewell and its customers, and to countless patients around the country.

The problem was that the machine’s manufacturer in Germany would take two weeks to get a technician to California with the proper replacement parts. Not good. Enter Mr. Tkachev with an offer to take the thing apart, figure out what makes it tick and do whatever it takes to get it back online. Needless to say, there were those who questioned the advisability of such a course of action, but Mike knew he could do it — all those years of military training weren’t wasted on him, and Jim Glidewell opted to give him the chance.

Mike worked into the night, eventually isolating the problem to a certain sector of the main motherboard, which he took home to test with his own special electronic diagnostic equipment. (Best not to ask.) By 4 a.m. he’d tracked the problem to a single chip that he was sure was the culprit.

When businesses opened later that morning, he rushed to an electrical supply shop to get a replacement chip. “No such thing” he was told by the man behind the counter. “Not in this country.” Turns out he was right. There was no U.S. equivalent for the German chip used in the machine.

Not to be deterred, Mikhail asked for the catalog to leaf through himself to find something, anything, that he could use to replace the faulty chip. Finally, he found an item that was close enough in function and size to the original that with some ingenuity and a hot soldering iron he could make it work, whether it wanted to or not.

Sure enough, before noon that very day, just as Glidewell managers were filing into a meeting where they’d decide what to do about the calamitous equipment failure, Mikhail was able to send the message up to the brass: “The machine is put back together, and it works. It works!”

Mikhail has gone on to devise dozens of ingenious solutions to problems, and new ways to accomplish old tasks in smarter, more efficient and more economical ways. He’s an important reason Glidewell is the competitive powerhouse it is, constantly offering its customers new products and better prices.

One such example is the magnetic articulator system marketed by Glidewell Direct. It’s an elegantly simple solution for dental technicians’ desire to hold impressions securely in place and then remove them quickly, without having to make a huge investment in a competing system. Yes, it was Jim Glidewell’s idea to develop such a tool, but it’s Mikhail’s creation, right down to the details of tooling and die-casting.

Of course, being the gentleman he is, Mikhail breaks into his typical bright-eyed, boyish grin when he discusses the articulator and credits his co-workers and especially Wolfgang Friebauer, the head of Glidewell’s R&D department, for bringing it into being. He even asked that Chairside® deflect credit to his machinist, Viktor Khivrenko.

Need proof of the Tkachevs’ success in America? Both of their children graduated college at the age of 18. Daughter Alona is now studying nursing at Long Beach State, and son Sergei, who earned a B.A. from UCLA at age 21, works at KPMG and is halfway though his CPA exams.

Meanwhile, Vladikavkas remains a small but technically advanced town in the Caucasus Mountains, now home to the Polymer Research Institute of Electronic Materials, a place Mikhail may have found employment had he stayed. And had the secret police approved.