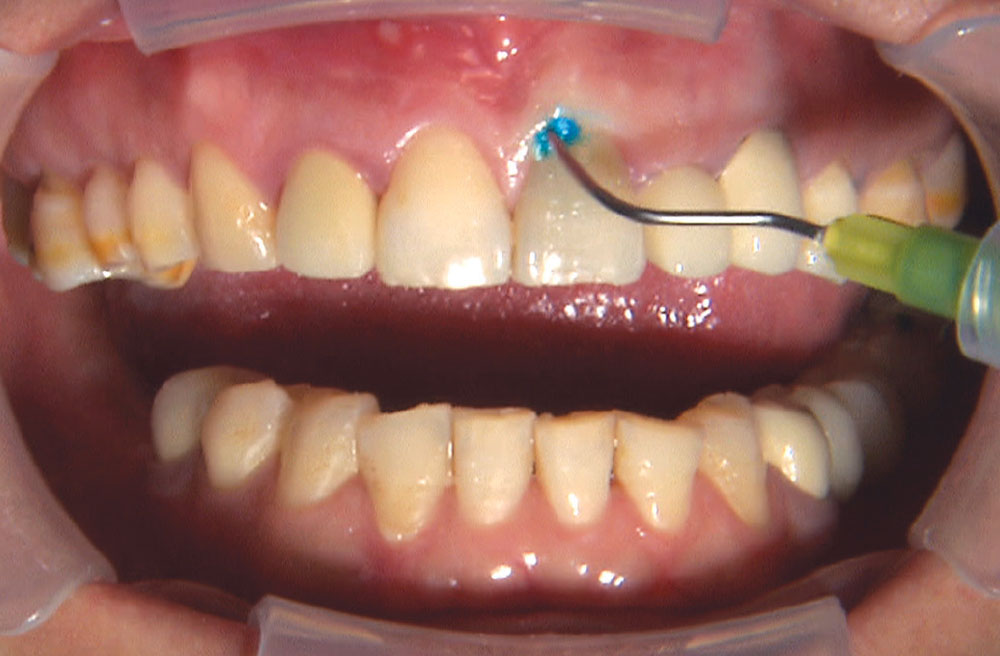

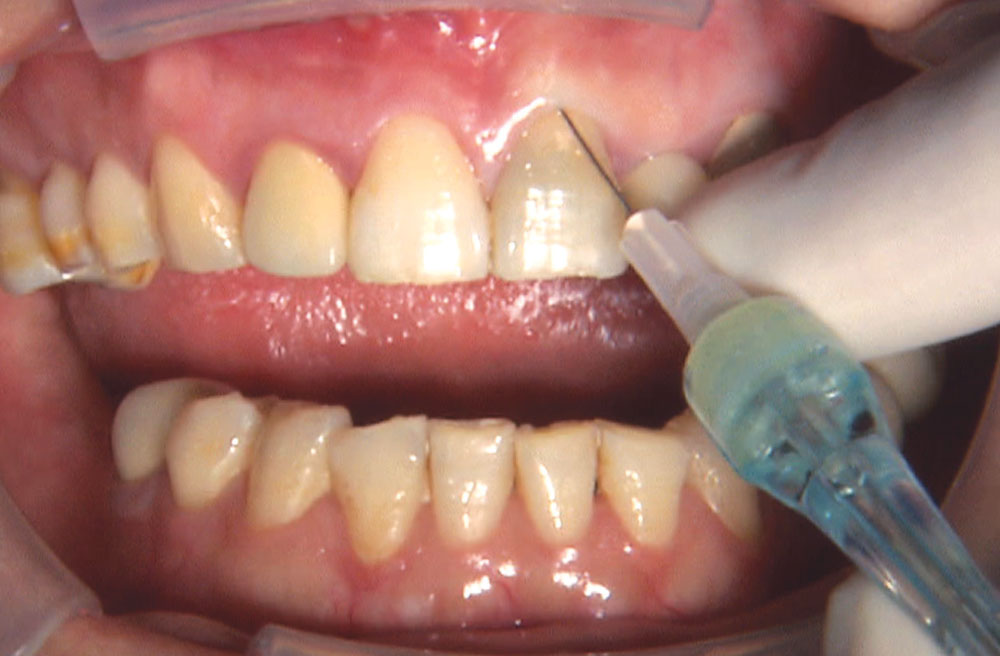

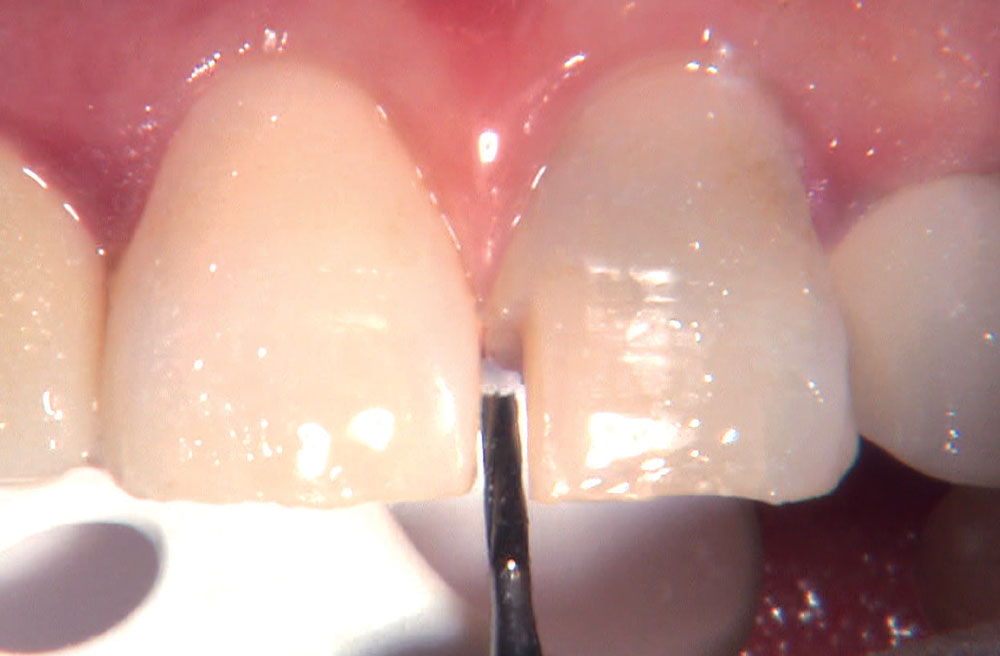

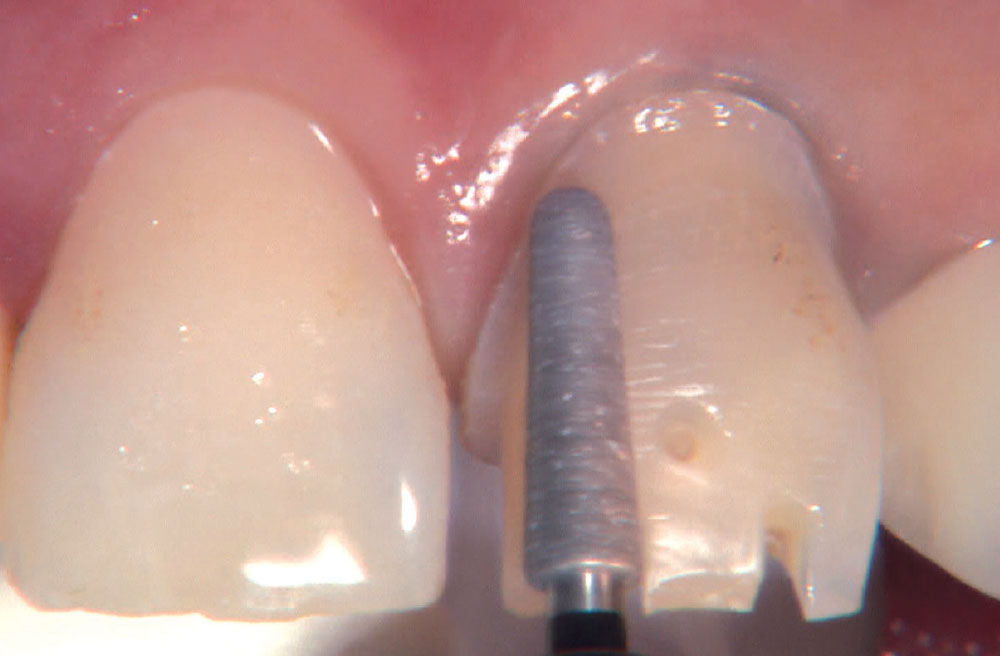

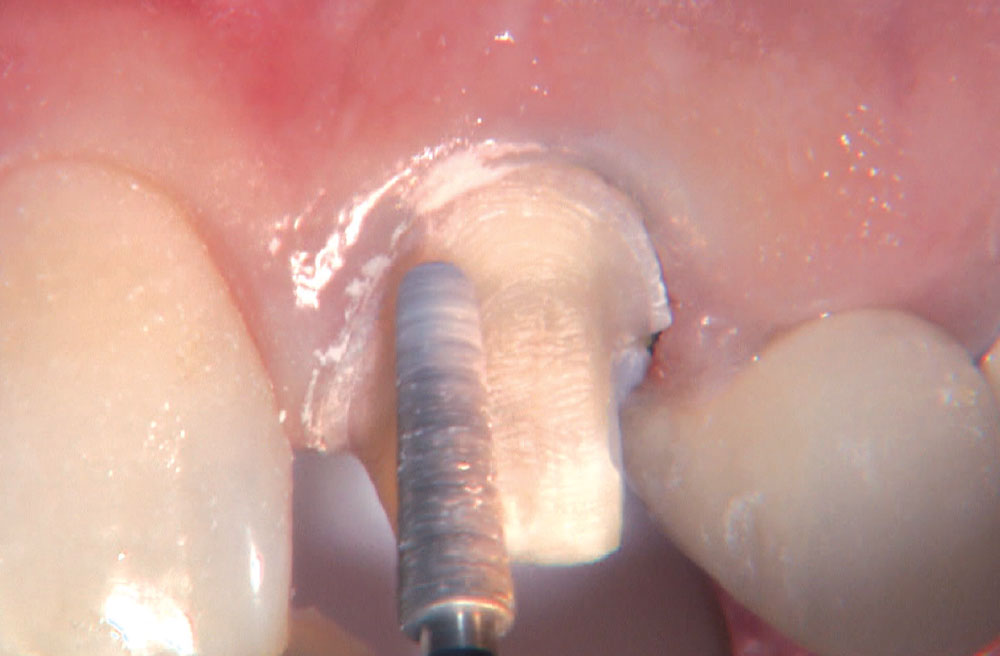

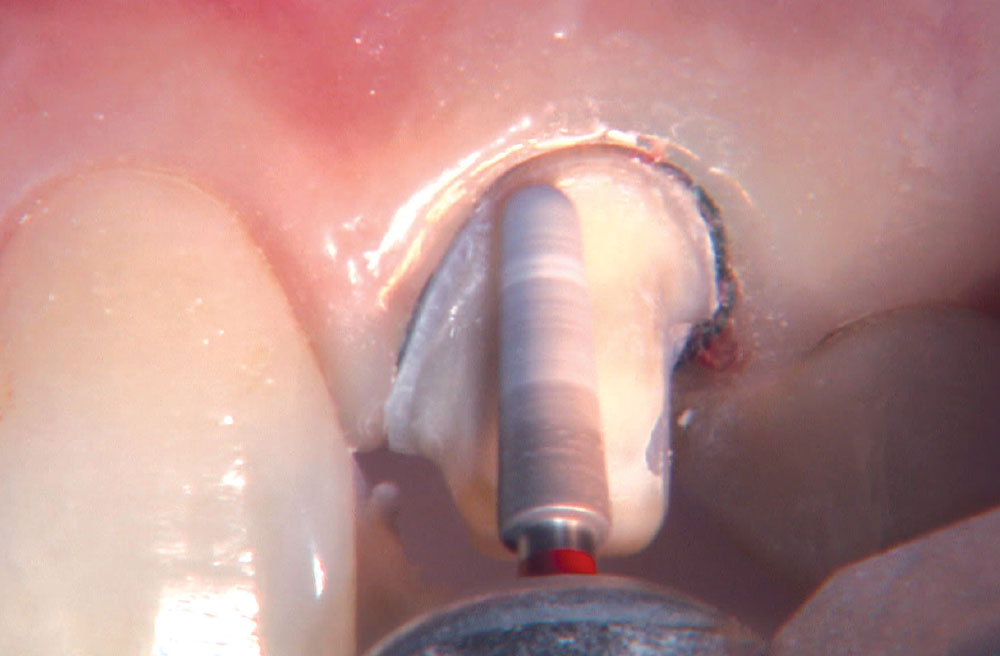

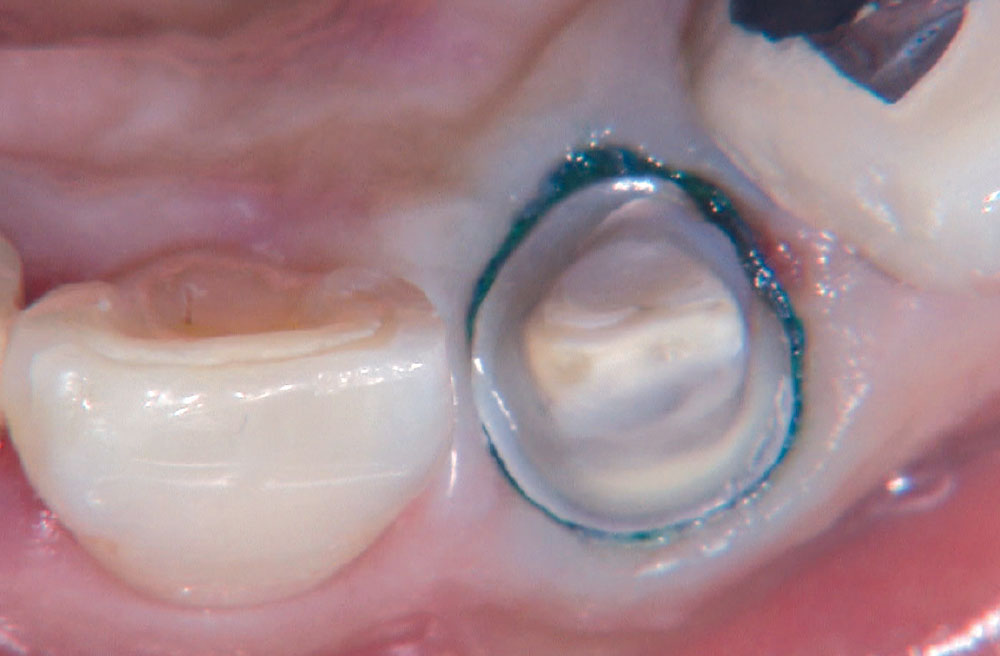

Photo Essay: Anterior BruxZir® Solid Zirconia Crown

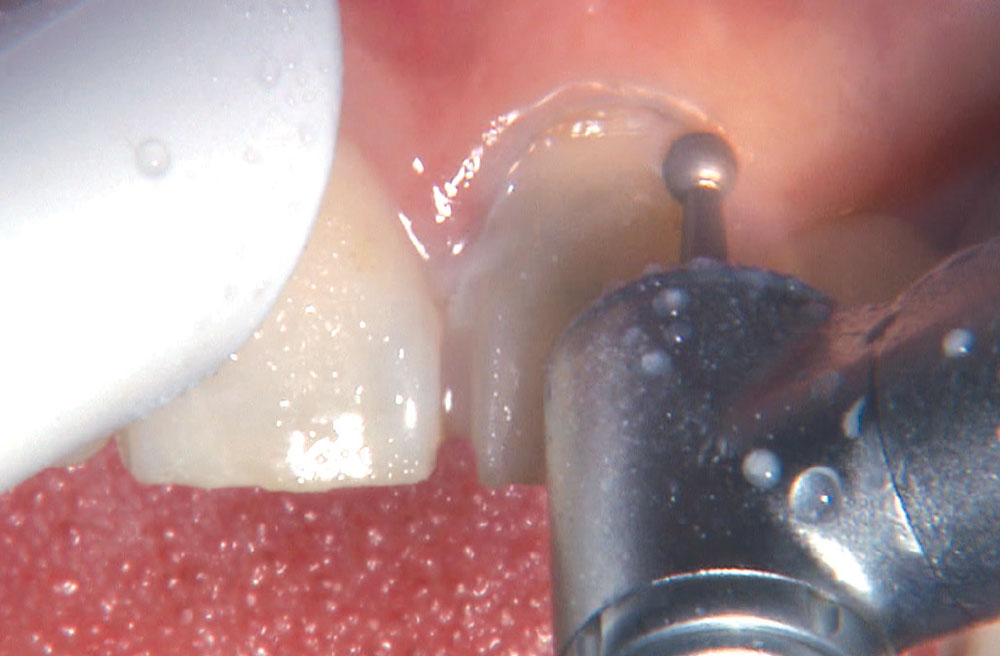

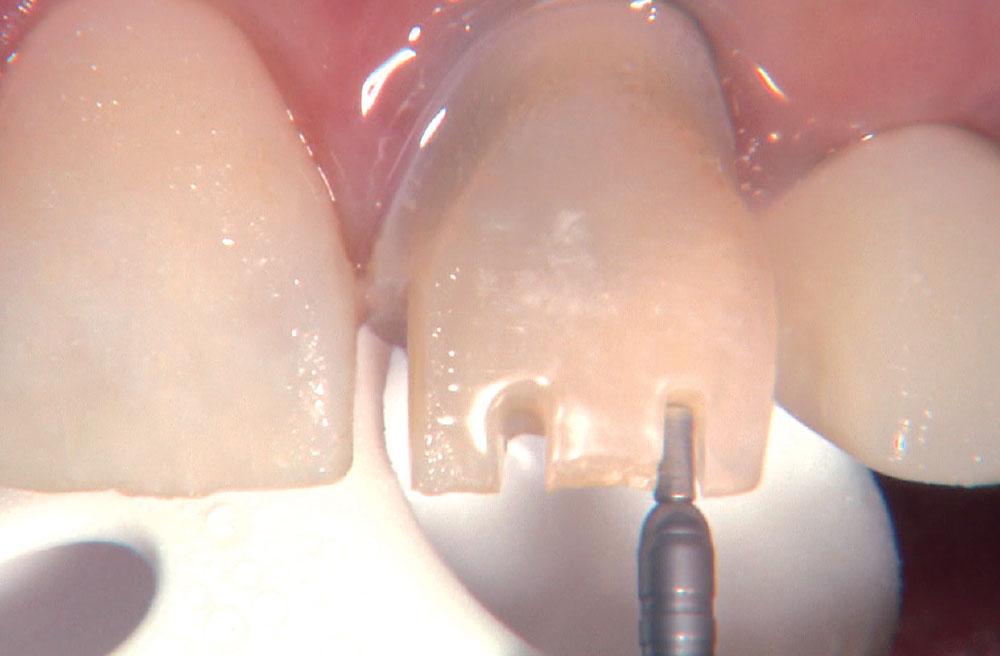

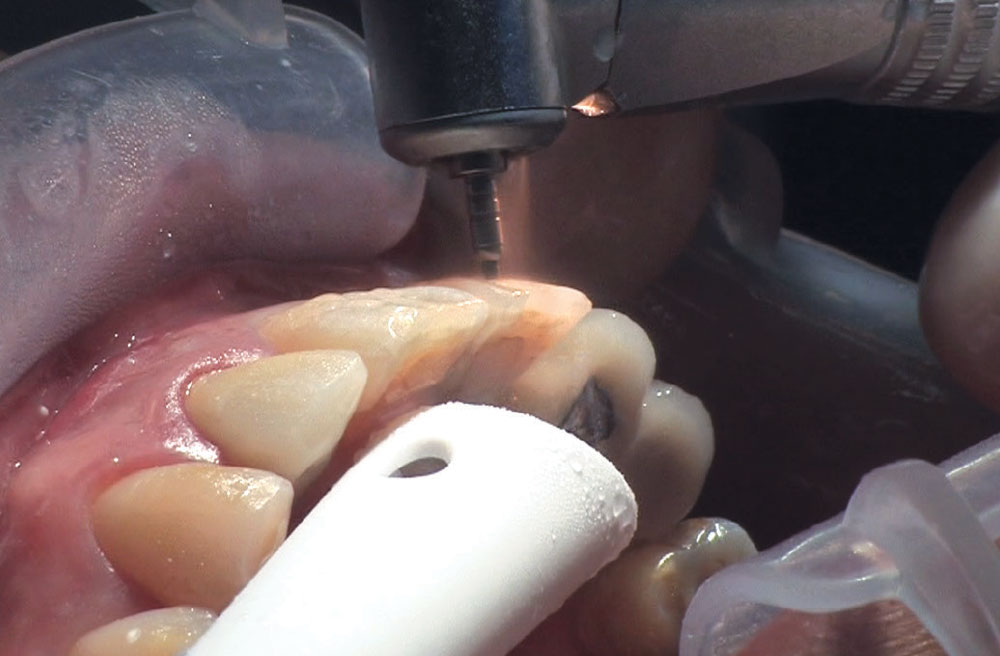

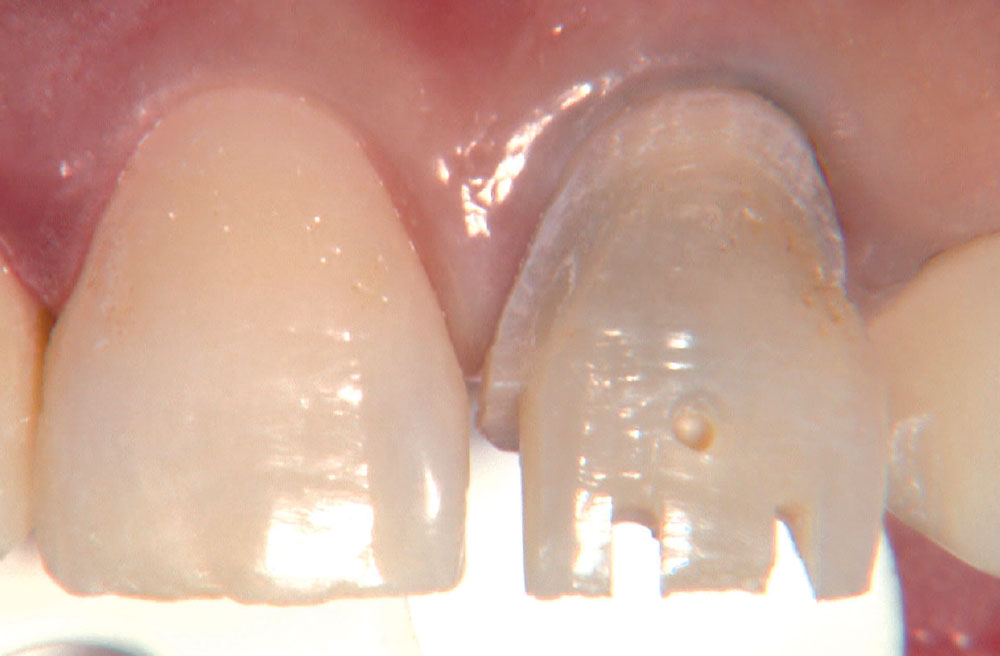

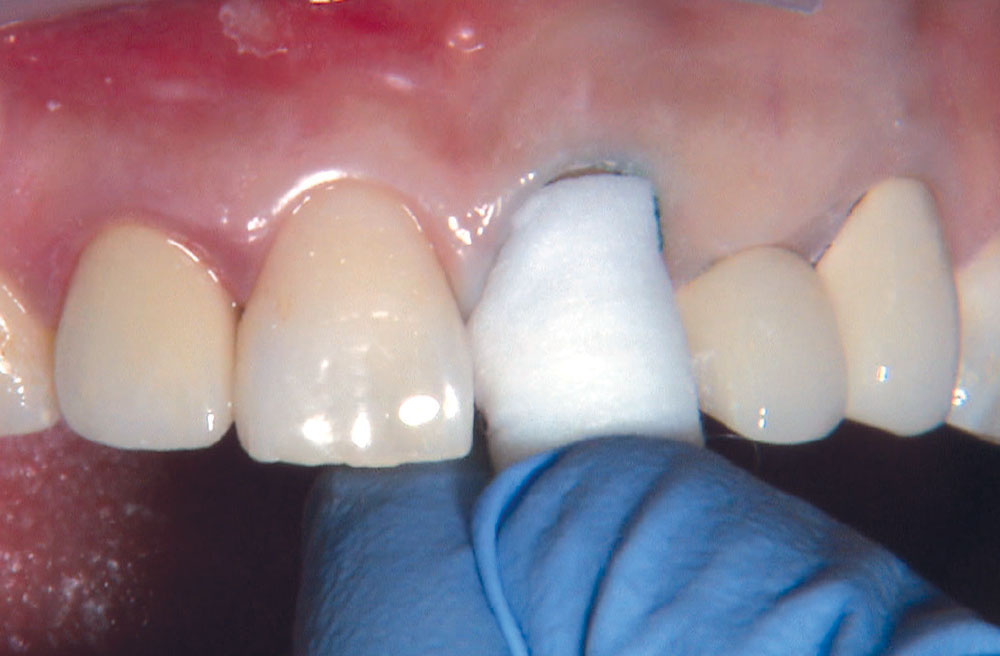

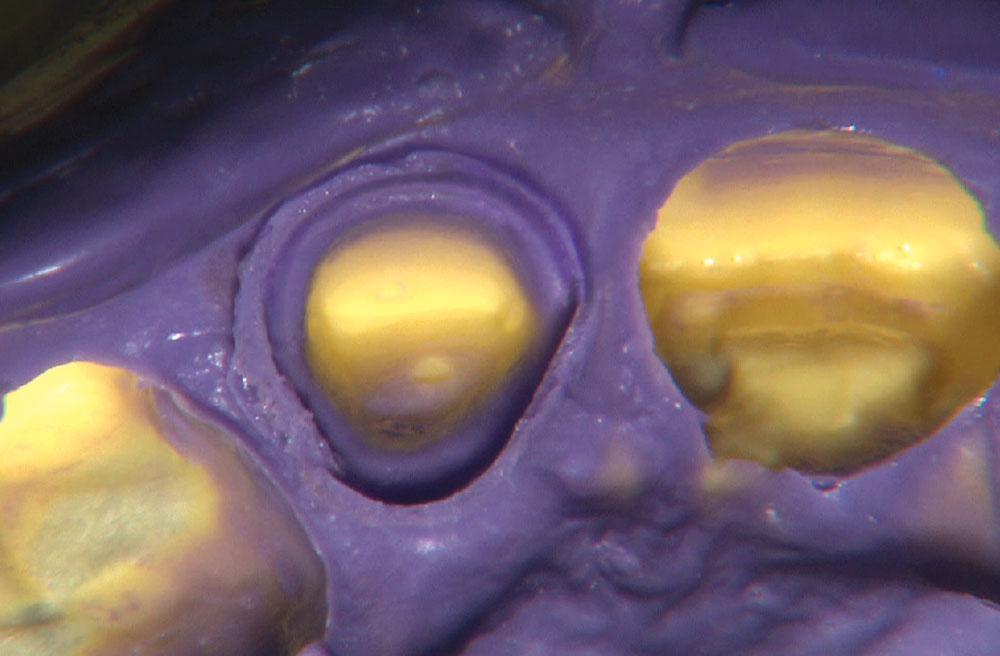

BruxZir® Solid Zirconia crowns & bridges were originally designed by Glidewell Laboratories as a replacement for posterior cast gold or metal occlusals, when the patient did not want any metal showing in his or her mouth. As dentists began placing BruxZir restorations and were repeatedly satisfied with the results, they started to prescribe BruxZir for bicuspids, as well. The lab realized that if dentists wanted to prescribe BruxZir in the anterior, the translucency of this material needed to increase. Our R&D team worked on this quietly and finally told me when they were ready to test it. They asked me for an esthetic challenge, so I decided to give them the tough one we all face: the single-unit central incisor crown adjacent to a natural tooth. This photo essay shows the clinical steps for placing an anterior BruxZir crown. For a crown that is 100% zirconia with no ceramic facing, the lab pretty much nailed it.