The Wynne Hybrid

Introduction

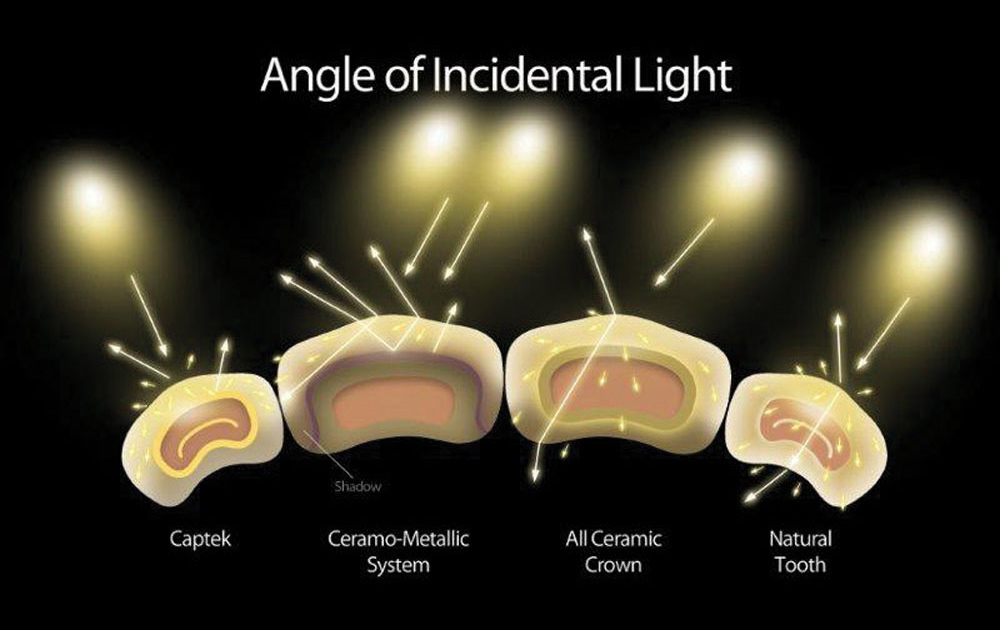

Advancements in material technology provide us with many opportunities to improve a patient’s smile. There are a number of new substrate-supported systems, as well as all-porcelain systems, to meet our demands as clinicians. These improved materials reflect, refract, absorb and transmit light in unique ways (Fig. 1). The selection of a material system now depends upon the patient’s clinical needs, assistance from the dental laboratory and the clinician’s personal material philosophy.

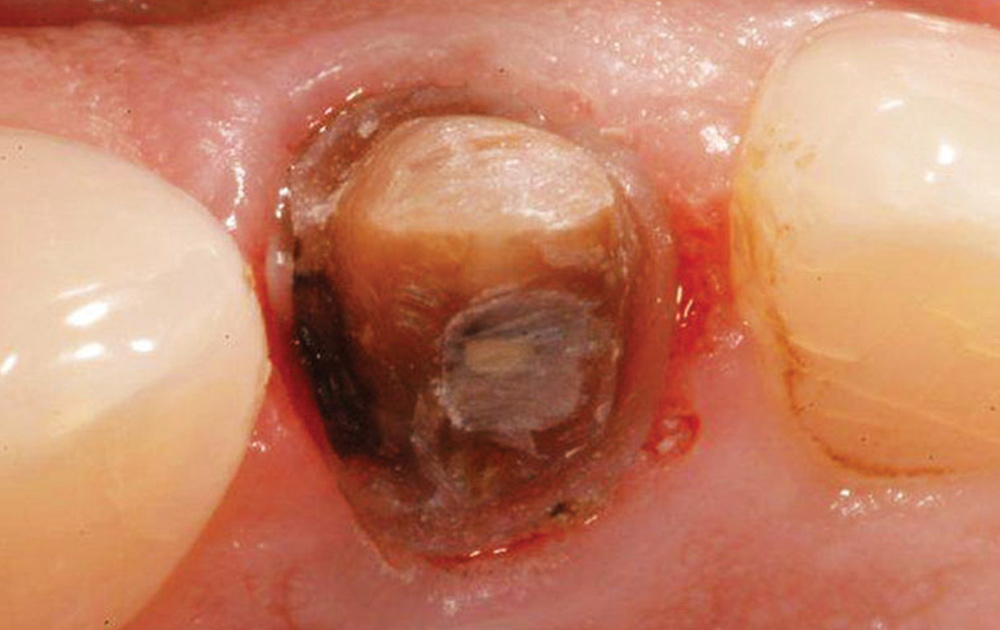

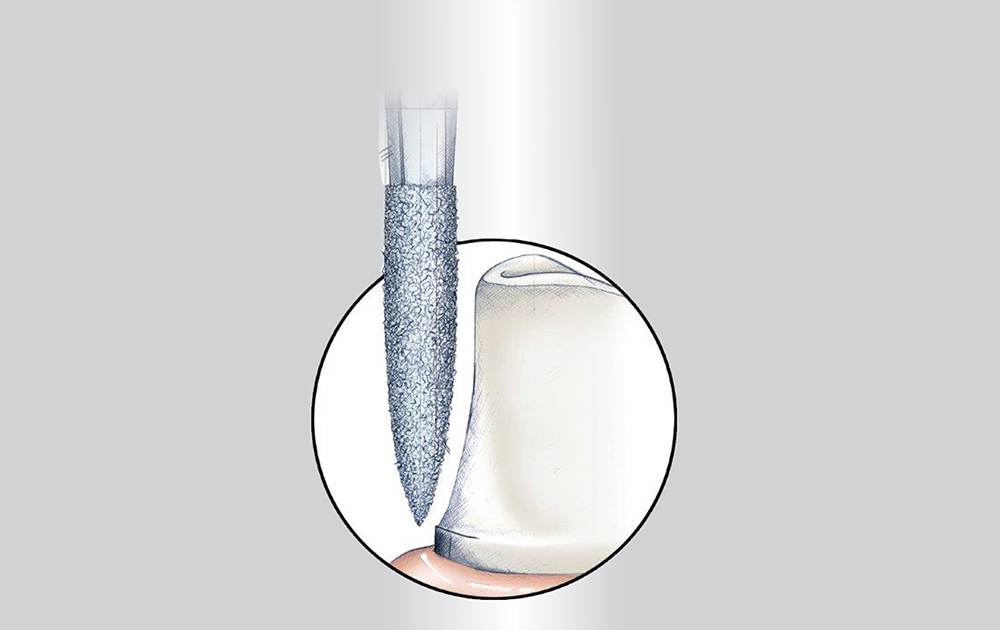

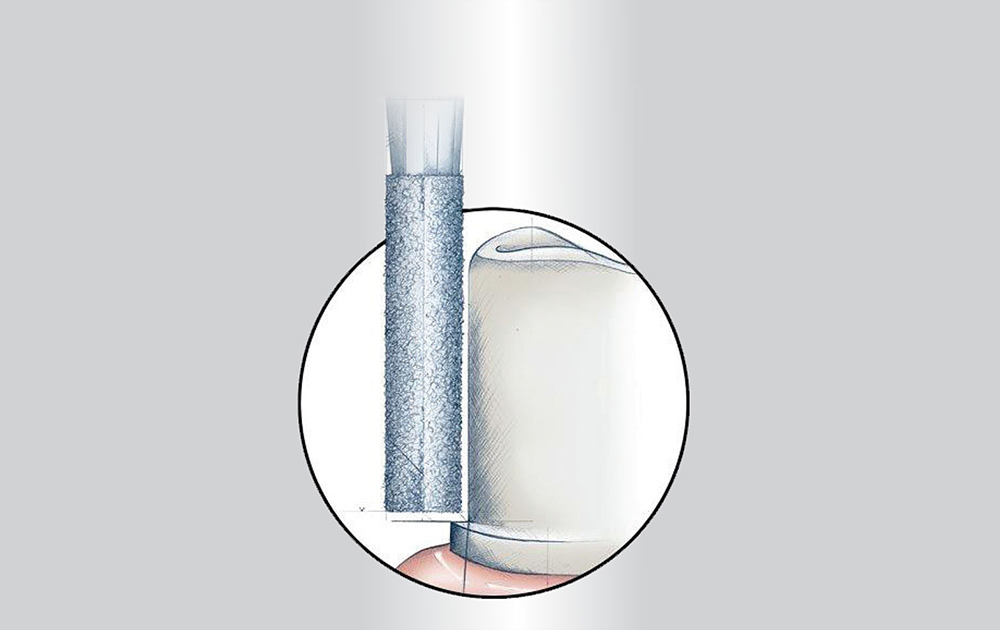

Dental material development seems to be moving in the direction of restorative material strength. However, Pascal and Urs state, “New restorative approaches should aim to create not the strongest restorations, but rather a restoration that is compatible with the mechanical, biologic and optical properties of underlying dental tissues.”1 If clinicians accept that notion, then the concept of “esthetic demands and functional risk” calls for restorations that have a high degree of versatility (Fig. 2). One such restoration design is the Wynne Hybrid. This unique restoration utilizes the antimicrobial benefits of Captek™ Nano (Argen Corporation; San Diego, Calif.) substructures (Fig. 3) to seal out and reduce harmful bacterial plaque with conservative preparations interproximally; maximizes abutment strength; and esthetically blends supragingival margins on the lingual and buccal.2

The Wynne Hybrid technique focuses on the lingual esthetics of maxillary teeth, in addition to facial esthetics. The lingual dark line around maxillary teeth has been referred to as the most overlooked esthetic zone3,4 (Fig. 4). As a result, many patients with small children or grandchildren have been asked, “Mom, Dad, Grandma or Grandpa, what is that dark thing in your mouth?”

The article that follows shares a rationale, as well as the clinical and laboratory processes of the Wynne Hybrid restoration.

Restorative Materials

Four groups of restorative materials are available for patient restorative needs.5 These groups are:

- Powder/liquid feldspathic porcelains

- Pressed or machined glass ceramic

- High-strength crystalline ceramics

- Metal ceramics

These restorative materials are listed in order of increasing strength and the amount of necessary tooth reduction. Captek, however, is a more conservative metal-ceramic preparation design. This relationship of material selection, strength factors and preparation requirements needs to be understood if the primary goal of the restoring clinician involves selecting the least invasive, longest-lasting restoration. According to Spear, “All teeth should be restored with the most conservative restoration that satisfies the patient’s esthetic and functional requirements.”6 Understanding material options allows the clinician to select materials on a tooth-by-tooth basis, as determined by the esthetic, functional and clinical circumstances of each tooth to be restored (Figs. 5–8).

Parameters of Material Selection

When choosing the optimal restorative material for each tooth, four criteria should be considered5:

- Substrate condition (amount and type of dentin and enamel)

- Flexure risk assessment

- Tensile and shear risk assessment

- Bond/seal maintenance risk assessment

These factors will dictate the strength requirements, the position of the final margin, tooth reduction and degree of transparency of the substrate.

Managing the Margin to Maximize Esthetics

All-porcelain systems help clinicians mimic the light transmission of enamel and dentin.7-9 Teeth in the esthetic zone can benefit from the esthetics provided by all-porcelain materials, but there are situations where strength is an issue. Bruxers or occlusally involved patients need additional restorative strength. Patients with flexure, as well as excessive shear and tensile stress risk, are included in this group as well.2 According to McLaren and Whiteman: “If a high-stress field is anticipated, stronger and tougher ceramics are needed. The restoration design should be engineered with such support that it will redirect shear and tensile stress patterns to compression. The substructure should reinforce the veneering porcelain by using the reinforced porcelain system, which is generally accepted in literature as a metal-ceramic concept.”5

The Wynne Hybrid

The Wynne Hybrid, as the name suggests, involves two margin designs: the facial and lingual pressed porcelain butt margins on definitive shoulder or chamfer margins. Interproximally, a knife-edge design developed to the edge with Captek Nano material is conservative but also bacteriostatic.2 In the author’s opinion, this interproximal design is also the easiest for the clinician to finish, especially in the often hard-to-reach molar interproximal area.

When underlying tooth colors are heavily stained, as is often the case when retreating old restorations, preparation blockout techniques that require more tooth reduction are often difficult to control (Fig. 9). Old metal posts in anterior endodontically treated teeth pose another challenge6 (Fig. 10). When we attempt to remove and replace these post systems, we run the risk of fracturing the tooth. The Wynne Hybrid can be utilized in such situations to resolve this issue in a conservative yet esthetic manner (Figs. 11, 12).

Another advantage of this design is the increase of the ferrule effect.10,11 This is due to the interproximal margin placement that engages more of the diameter of the tooth. The reasoning behind this is that crowns with metal copings are less likely to snap off with the tooth still inside should they receive a blow.

Biological Width Considerations

When restoring teeth, biologic width issues can often be a concern. The gold knife-edge margin is the most controllable of all margins in the posterior interproximal areas. Some clinicians advocate a 360-degree porcelain butt margin around all teeth. The key to predictable margins is the ability to control the finishing of all 360 degrees of tooth margin. Anterior teeth have interproximal margins that can be reached and highly polished. However, as we move from premolars to molars, the facial-lingual dimension of the contact space increases. This diminishes the ability of the clinician to control the interproximal margins. Concave root surfaces eliminate or greatly diminish the chance of properly finishing the margin. This knife-edge margin is more easily cleaned with an explorer and floss. The facial and lingual porcelain butt margins are entirely accessible and can be finished with the clinician’s preferred technique.

Wynne Hybrid Prep

Preparing a tooth for the Wynne Hybrid requires only four burs: the 701 bur (SS White 9990935); a gold margination diamond (Brasseler 686231-012); a flat-topped polishing diamond (Brasseler 8837-012); and a pear-shaped diamond (Brasseler 7408). The Wynne Hybrid crown technique is detailed below.

- The Wynne Hybrid is a classic porcelain fused to metal preparation. Therefore, 1.5 mm to 2 mm of occlusal reduction is necessary. The 701 bur is 0.5 mm in diameter at the tip and 1 mm in diameter at the shank. Try to visualize the clearance with the opposite arch closed. This is the initial occlusal reduction.

- At this point, old restorative material and decay can be removed. The tooth can now be based out and built up and readied for continued prepping.

- Next, clear out the contacts to increase access to the interproximal areas.

- Scribe a line completely around the crown, simulating the location of the final margin. This is typically performed at the height of the gingival.

- Now, place the interproximal margins with the Brasseler 686231-012 diamond (Fig. 13).

- Place the facial and lingual butt margins with the 701 bur and polish with the Brasseler 8837-012 polishing diamond (Fig. 14). The depth of this butt is from 0.8 mm to 1.5 mm, depending on what is trying to be accomplished. The shallow margin obviously removes less tooth structure, but more reduction may be needed to cover up dark tooth structure.

- Finally, use the Brasseler 7408 pear-shaped diamond to polish the occlusal surface.

The Wynne Hybrid design gives you three basic options:

- Facial porcelain butt with mesial, distal and lingual gold collar

- Facial and lingual porcelain butt with mesial and distal gold collar

- Lingual porcelain butt with mesial, distal and facial gold collar

Case Study

This case involved six posterior teeth on the patient’s right side, which had previously been treated with full crowns (Fig. 15). Over the years, recession had begun and progressed until a significant amount of tooth structure was exposed. It was decided that teeth #2–4 and #29–31 would be restored with Captek Nano material.

Captek Nano internally reinforced gold copings were fabricated at Glidewell Laboratories, a Captek Advanced Certified lab. Notice the cut-back on the facial as well as the lingual margins (Figs. 16–20). The patient was extremely happy with the esthetics of the Captek Nano restorations (Fig. 21).

In focusing our concerns on the esthetic nature of contemporary restorations, we often limit our focus to the facial aspect of teeth. If we can comprehend all the visual possibilities, new areas of focus will appear. The lingual aspect of most maxillary teeth falls into this new focus. Incorporating the facial and lingual zones as esthetic areas will generate a higher level of esthetics for the patients we treat. With the Wynne Hybrid, esthetics can be balanced with a conservative and supportive preparation design, high porcelain fracture resistance and biological health.

Benefits of the Wynne Hybrid Design

- Block out color

- Compatible with bleach shades

- Increase ferrule effects

- Control biologic width

- Eliminate painful palatal injections

- Bacteriostatic interproximals

- No periodontal encroachment on facial or lingual

- Use in esthetic zone

- Easy cement clean up

- Color compatible with most restorations

Summary

Opinions on material selection abound. And, for now, there is no perfect dental restoration or material combination. Many times a single system can be utilized for all of the patient’s restorative work. However, the patient may best be served with a combination of systems. It is clear that stronger systems, such as the time-tested PFM, may serve better in the functional zone, while all-porcelain systems — or modified metal designs like the Wynne Hybrid design — may be better indicated in the esthetic zone. Strong, healthy and esthetic restorations are the result of deciding what is best for the individual tooth. Today, with clinicians having access to so many restorative material options, no patient should have to settle for anything less than ideal.

Dr. William Wynne maintains a private practice focused on esthetic and restorative dentistry in Raleigh, North Carolina. Contact him at raleighareadentist.com or 919-851-3716.

Acknowledgments

- Illustration by Arturo Lima (Fig. 1).

- Dentistry and clinical photography by Dr. Hedstrom (Figs. 5, 6, 8).

- Laboratory fabrication and photography by Alvin Fillastre, III, CDT (Fig. 7).

- Laboratory fabrication by Glidewell Laboratories with photography by Chris Lowthorp, CDT (Figs. 16–19).

- Annie Chu, RDH, for her editing and computer skills.

References

- Magne P, Belser U. Bonded porcelain restorations in the anterior dentition: a biomimetic approach. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co.; 2002. p. 59.

- Goodson JM, Shoher I, Imber S, Som S, Nathanson D. Reduced dental plaque accumulations on composite gold alloy margins. J Periodontal Res. 2001 Aug;36(4):252-9.

- Dudney T. Achieving an ideal restorative material. Inside Dent. 2011 Dec;7(2):58-63.

- Wynne W. Margin design in the most overlooked aesthetic zone. Dent Today. 2006;25(10):126-7.

- McLaren EA, Whiteman YY. Ceramics: rationale for material selection. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2010 Nov-Dec;31(9):666-8, 670.

- Spear F. Treatment planning materials, tooth reduction, and margin placement for anterior indirect esthetic restorations. Adv Esthet Interdisciplinary Dent. 2005;1(4):4-13.

- Krasteva K. A technique for aesthetic, natural-looking anterior metal-free restorations. Dent Today. 2001 Oct;20(10):82-4, 86-9.

- Roberts J, Roberts M. Achieving optimal aesthetics using contemporary porcelain materials: a case report. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2004 Aug;16(7):495-502.

- Little DA. Illustrating predictable anterior and posterior esthetics results: two case studies. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2002 Mar;23(3 Suppl 1):17-23.

- Shoher I, Whiteman A. Reinforced porcelain system: a new concept in ceramometal restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 1983 Oct;50(4):489-96.

- Jotkowitz A, Samet N. Rethinking ferrule – a new approach to an old dilemma. Br. Dental J. 2010;209(1):25-33.