One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: Interview of Dr. David Hornbrook

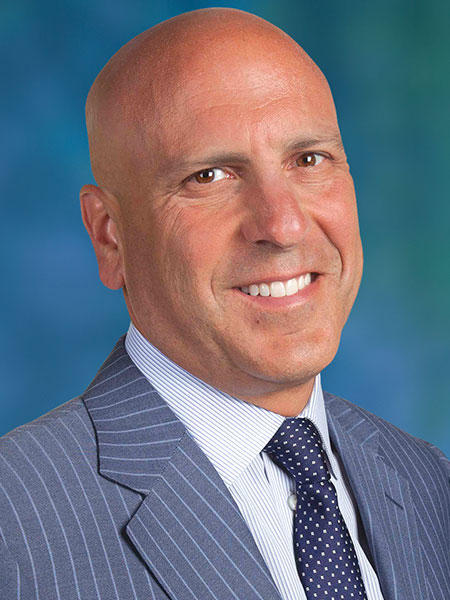

It was my pleasure to interview one of my clinical mentors, Dr. David Hornbrook, for this issue of Chairside® magazine. David is someone whom I have followed since I graduated from dental school, when I started taking his courses at Las Vegas Institute for Advanced Dental Studies (LVI), PAC~live and the Hornbrook Group. Over the years, I’ve continued to follow David and look up to him as a clinician and friend.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: Good morning, David, it’s wonderful to have you here with us.

Dr. David Hornbrook: Thanks, it’s great to be included.

MD: People always say, “Now is the best time to be a dentist.” (With perhaps the exception of the 1960s, before the air-driven handpiece was invented and everything was belt-driven.) But as I reflect on my more than 20 years in practice, it seems that things just continue to get better. Do you feel that 2011 is a great time to be practicing dentistry?

DH: Absolutely. There are two things we need to look at. One is, obviously, that the economy has changed a little bit. There may be people reading this who say, “I’m not doing what I was doing two years ago in smile designs and discretionary dentistry.” But if we eliminate that aspect of it, this is the best time to be a dentist.

The advantage of where we are now is that we are no longer faced with the many limitations and compromises we’ve historically faced during treatment planning. Materials are more esthetic, and adhesive dentistry has allowed us to be more conservative. Today, the only limitations we face are those of the clinician’s imagination.

MD: Well, let’s back up to what you said about the economic slowdown. I can tell you that, at least from the lab’s perspective, the economic slowdown over the past two years did happen — you are right on the money. If we look at our veneer sales, they definitely decreased over that time period. No one is imagining that. This isn’t a rumor running rampant through dentistry; there was a serious cutback in the number of elective cosmetic procedures.

Over the past two years here at the lab, only a couple of products have grown. One of them is an esthetic product (in the sense that it’s a great-looking product): IPS e.max® (Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, N.Y.) crowns. IPS e.max veneers have grown as well. People obviously still need full-contour restorations, so those may not be elective. At any rate, IPS e.max has continued to show an impressive growth curve over the last couple years. I’m guessing you’re a pretty big fan of this product. Tell me a little bit about the impact IPS e.max has had on your practice.

DH: You are absolutely right to say that I’m a big fan of IPS e.max. It’s an unbelievable material. For those readers who aren’t familiar with this product, IPS e.max is a lithium disilicate material that can be waxed and pressed or fabricated using CAD/CAM.

When waxed and pressed, kind of like we’ve done with IPS Empress® (Ivoclar Vivadent) and leucite-reinforced ceramics for the past 20 years, we use the lost-wax process (just like we’d cast gold). It can also be made using CAD/CAM technology, whether in the office with CEREC® (Sirona Dental Systems; Charlotte, N.C.) or E4D (D4D Technologies; Richardson, Texas), or in the dental laboratory.

IPS e.max has filled an existing void in dentistry. It is a highly esthetic material — as you mentioned, it approaches the esthetics of anything we have in dentistry right now — and it’s amazingly strong. We now have a ceramic that’s four times stronger than the ceramic we’ve put on PFMs for the last 60 years.

IPS e.max has filled an existing void in dentistry. It is a highly esthetic material — as you mentioned, it approaches the esthetics of anything we have in dentistry right now — and it’s amazingly strong. We now have a ceramic that’s four times stronger than the ceramic we’ve put on PFMs for the last 60 years. I mentioned earlier about options in treatment planning: Now I can look at even a second molar on a bruxer that has decreased vertical dimension and give the patient a restoration that is esthetic, conservative and strong.

MD: I distinctly remember placing my first IPS e.max crown. It was on a friend’s wife, and it was at the end of a two-year period in which I did nothing but zirconia-based restorations. We were struggling to blend the zirconia restorations with the adjacent teeth because we were dealing with coping shade issues and with dentists under-reducing teeth, especially in the gingival third.

When lithium disilicate came out, I must admit I was a little suspect. Ivoclar was releasing this material for the third time, and I wondered if it would work. The first IPS e.max crown I put in was so beautiful that it blew me away. It was the kind of thing you looked at and said: “Wow. If this is going to stand up to the types of wear and tear we see in the mouth, this material is going to be successful.”

How neat is it that a material can be used for almost any clinical indication — inlays, onlays, crowns and even veneers? I recently heard a rumor that some of the esthetic institutes were thinking of switching over to IPS e.max veneers. What are you teaching in your clinical course now, and how do you feel about IPS e.max veneers?

DH: Well, by the time this article is published, my opinion may change based on the fact that Ivoclar is introducing even better ingot and block shades. I know some people will read this and say: “IPS e.max? It’s kind of gray. It’s kind of opaque. It doesn’t look as good as IPS Empress …” That was the IPS e.max of a year and a half ago, when Ivoclar didn’t have available the many translucent and esthetic ingots that are now offered for CAD/CAM or for pressing. And now they’ve introduced ingots that mimic what we’ve always seen with Empress, which is what I would call my standard for anterior esthetics. To answer your question, today I’m still a fan of IPS Empress in the anterior and it is still my “go to” material. If you came into my office or into my teaching center and you were going to do six, eight, 10 veneers, IPS Empress would still be my first choice. I just think it interacts with light a little better than lithium disilicate. But as we get more experience with the new Value ingots, that preference may change. I seated 10 maxillary anterior veneers this week using the new V1 ingot, and the case was beautiful.

We are also now doing prepless and very minimal-prep IPS e.max veneers, because at 0.2 mm or 0.3 mm thin, this material exhibits incredible marginal integrity. Even being this thin, they are very high strength and very easy for the laboratory to finish down at the margins. We’re doing anterior 3-unit bridges in IPS e.max, and we’re getting esthetics that approach IPS Empress. So we’re still teaching IPS Empress. But, then again, three months from now when you ask me this question I might say: “Who’s using IPS Empress anymore? Not me.” This is what makes dentistry so exciting and fun!

MD: My personal viewpoint is that if I’ve got to do a veneer on tooth #9, and tooth #8 is a virgin tooth, I am going to use IPS Empress. Like you, I don’t think there’s anything as lifelike as IPS Empress somewhere between 0.3 mm and 0.6 mm thick. It just looks more like natural tooth structure than anything else. But I’ve started to change a little bit — and I’m not as demanding esthetically as you are. When I get to an 8-unit veneer case, I like the idea — and we can see from the numbers that dentists liked the idea, too — of having a veneer material that’s three times as strong as IPS Empress. Dentists have had problems with chipping and they’ve had some breakage. Maybe it was due to poor prep design or not checking the occlusion close enough, but dentists seem to like the idea of having a stronger material. And, of course, when you have six, eight, 10 veneers lined up next to each other, it’s not the same kind of thing as it is with a single tooth. Do you think that’s a reasonable approach for the average dentist?

DH: Absolutely. Not even for the average dentist — every dentist. If we can deliver a restoration that is two to three times stronger than anything else we can offer and it doesn’t compromise esthetics, I think that’s definitely the way to go. We’re looking at this material very seriously. I mentioned that Ivoclar just introduced its IPS e.max Press Impulse Value ingots. I did another case recently using these V ingots — two cantilever bridges replacing laterals off the canine and then eight other veneers — and it was absolutely beautiful. I actually had the lab make two sets: one IPS Empress and one IPS e.max. After trying in both cases, I chose IPS e.max. Needless to say, we’re very excited about this material.

MD: I agree, and dentists are certainly voting here at the laboratory with their wallets, as well.

I remember one morning about a year ago, I opened a journal and there was Dr. David Hornbrook doing a no-prep veneer case! I wasn’t sure if this was a hostage situation in which you had a gun to your head, but I was caught so off guard that I spilled my coffee; I didn’t know what might have prompted this. I have a feeling it’s material advancements. And, of course, as somebody who performs such esthetic services as yourself, the abuse of the no-prep veneer concept was probably something that bothered you a little bit. But I really thought it was a great sign. And you — being so open-minded to go forward and try one of these cases, and then publish the case! It was a gorgeous case, by the way.

DH: Well, thank you. I think prepless or very minimal prep veneers are a technique that every dentist needs to explore. Obviously, it’s public-driven because a major dental manufacturer markets prepless veneers to the public, so now patients are asking for this procedure. But I think it’s been abused. We see very compromised results with this technique more often than not. You work with a dental laboratory, so you understand the importance of the communication process. The communication between the ceramist and the dentist is so crucial. I think a lot of dentists were, and still are, doing these prepless veneer cases without really understanding the indications and contraindications of this procedure, and we see some really ugly and even unhealthy cases, especially tissue-wise.

I practice dentistry three to four days a week, and my patients were asking about these prepless veneer cases. And I really wanted to explore this more closely: Was it the material itself, the lack of case planning or the technique? So I went back and worked with laboratories and materials and ideal cases. Together we established some planning protocols that have yielded some surprisingly unbelievable results, esthetically and functionally, with prepless veneer cases. It’s an opportunity available for patients and doctors. As I teach, I find that a lot of doctors refuse to prep virgin enamel. This refusal limits their ability to offer their patients some beautiful smiles. Prepless veneer cases, when planned properly, are a viable alternative to prepped veneers.

MD: That’s interesting. I’ve never heard a dentist say, I refuse to prep virgin enamel. If somebody were to make that argument, I would have to assume they were probably doing lots of inlays and onlays. We certainly see lots of virgin enamel on very healthy cusps being prepped in the name of insurance-approved crown & bridge. I don’t know why they would find it to be different just because it was in the anterior. You know what I mean?

I hear and see it all the time. I see dentists who will prep a full crown instead of an inlay. Or they’ll prep virgin teeth on each side of a missing tooth to place a 3-unit bridge, but they won’t do a 0.5 mm depth cut on an anterior tooth. It amazes me.

DH: I totally agree. But I hear and see it all the time. I see dentists who will prep a full crown instead of an inlay. Or they’ll prep virgin teeth on each side of a missing tooth to place a 3-unit bridge, but they won’t do a 0.5 mm depth cut on an anterior tooth. It amazes me.

MD: To me, no-prep veneers really are a great finishing technique. I do hardly any no-prep cases where all eight or 10 units are no-prep veneers. But I do see cases where we will replace, say, old PFMs on tooth #7 through tooth #10 with some IPS e.max crowns. And then I will place no-prep veneers on the cuspids and the bicuspids and finish out the whole smile without having to do any additional preparation. That’s what I mean by a finishing technique: It is a great way to finish out a smile when it’s done in conjunction with other restorations.

DH: I agree, especially in this baby boomer age. A lot of these people went through ortho as a teenager and had their first bicuspids extracted. Now their posterior quarters are collapsing and they want a nicer looking anterior smile because of wear or discoloration. You can do veneers, or you can replace existing crowns and then place very conservative veneers on the premolars and develop a beautiful smile.

MD: When I first learned about esthetic techniques in your courses (back in 1995), we were doing fairly aggressive preparations in the dentin when placing IPS Empress veneers. And, as time has gone on, I have found that because of improvements in ceramic materials, we can achieve similar results with less reduction, assuming that the tooth is not way out of an ideal arch form and it’s just an esthetic issue. I like the idea of minimal-prep veneers, which, to me, is something that has all the margins still in enamel. I like the idea of bonding to enamel and keeping it intact. Do you find that minimal-prep veneers, where you’re not necessarily exposing dentin, are something that you are using more on a day-to-day basis?

What we recommend now is 0.3 mm to 0.5 mm depth cuts, assuming that the tooth is ideally positioned in the arch. So, unlike in the past, when most of my preparation for a veneer was in dentin, most of it’s now in enamel.

DH: When I first started teaching, around the time you went through my courses, I think it was also the inexperienced ceramist who established some of the “ideals” of veneer preparation. IPS Empress was new to ceramists. It was a monolithic material. They didn’t really understand how to use the different opacities and translucencies in a very thin environment. So they said, give us some more room because we just don’t get it. And we would prep 0.7 mm to 1 mm, and they would want the contacts broken. It was a new concept to them. We were teaching very aggressive preps in the mid 1990s. In the last four or five years, we’ve really done an about face. And what we recommend now is 0.3 mm to 0.5 mm depth cuts, assuming that the tooth is ideally positioned in the arch. So, unlike in the past, when most of my preparation for a veneer was in dentin, most of it’s now in enamel.

MD: Do you find that you enjoy bonding to enamel more than dentin, or is it not a big issue for you? I hear from dentists, whether it’s postoperative sensitivity or not being sure how much they’re supposed to dry the tooth off, that they really like the idea of etching enamel. Being able to dry it to your heart’s content, see that nice frosty look. For those of us who are kind of old-school dentists, it feels comfortable in a sense. It’s something that we grew up with.

DH: Personally, I don’t really have a problem bonding to dentin. We’ve been doing it for almost 15 years, and I feel the predictability is there. But, I agree: I think that dentists still struggle, even to this day, with this whole total-etch and how wet is wet and how dry is dry concept. Most clinicians feel a little more comfortable being able to etch, rinse and dry as much as they want and get success. I think we’re going to see increased predictability, less standard deviation and less failure when the restoration is primarily in enamel.

MD: I actually think that we’ll see more of these restorations diagnosed. Obviously, there’s talk of over-diagnosis of veneers, but I think that’s by a small percentage of dentistry. Many dentists still don’t talk about this type of esthetic dentistry because they’re not totally confident in their ability to get a great non-sensitive result doing it completely on dentin. They seem to like the idea of bonding to enamel, and they know it works, and they get less post-op sensitivity. As a result, they’re going to be more confident in their procedures.

DH: I agree with you.

MD: Speaking of total-etch versus self-etch, for your direct-placed restorations in the posterior, are you using self-etch at all? Or are you still a total-etch guy?

DH: I’m definitely a total-etch guy! In fact, I’ve actually gone back to fourth generation dentinal adhesive systems. So, I etch, and then utilize a separate solution for the hydrophilic primer and a separate solution for the hydrophobic adhesive.

MD: So you’re back to the regular two-bottle system. What are you using?

DH: I’m using ALL-BOND 3® (Bisco Inc; Schaumburg, Ill.). I like Bisco products and respect Dr. Byoung Suh and the research being done at his company. If I look back historically, what I would consider the gold standard would be ALL-BOND 2 and OptiBond® FL (Kerr Corporation; Orange, Calif.). And the only problem, at least that I saw, primarily as an educator, was that ALL-BOND 2 was acetone-based, so it was a little more finicky. What Bisco did a few years ago was change the hydrophilic carrier to alcohol. Now we have what I would consider a new gold standard. It’s alcohol based, and you can use it for every type of restoration you place in your office. Too many clinicians have too many bonding agents in their refrigerator. Unless they can get an adequate amount of light to polymerize the material, anything but a fourth-generation adhesive will lead to a compromised result.

MD: It really is kind of funny. I don’t know how many times in dentistry we’ve seen dentists take a step backward from what the latest and greatest is, with maybe the exception of digital impressions, which tend to be more difficult and more time consuming than conventional impressions. You look at the way things went to one bottle and then all of a sudden we have self-etching in one bottle. It began to look like: “Wait a minute. Are we doing this for us, are we doing this for the quality, or are we doing this for our patients?” So it’s interesting to hear that you’ve gone back to something that’s time tested and proven. It does take a little more time, but you feel it’s better. I know you’re not going to go back to a self-cure composite instead of light-cure composites or a belt-driven handpiece. You must really feel in your heart that this is the right thing to do.

DH: I do. I have not seen the sensitivity that a lot of people saw with the total-etch. Obviously, we’re isolating and controlling that surface moisture, not over-etching the dentin. But it’s something where I have predictability; I have success; I don’t have much postoperative sensitivity; I don’t see premature failure; and I can look back and show you 15 years of clinical experience, as well as excellent research.

The problem with today’s bonding agent chemistry is that it changes too fast. You’ll see a study on a self-etching primer that bonds to enamel that was carried out over a period of 36 months, and that material has changed chemistry since the article came out. So we can’t look at these and say this is going to have long-term success, where we can with total-etch systems.

The problem with today’s bonding agent chemistry is that it changes too fast. You’ll see a study on a self-etching primer that bonds to enamel that was carried out over a period of 36 months, and that material has changed chemistry since the article came out. So we can’t look at these and say this is going to have long-term success, where we can with total-etch systems.

MD: Does this mean that you have not played with any of the self-etching flowable composites yet?

DH: I’ve played with them, but I haven’t used them clinically except to alleviate sensitivity in gingival abfraction lesions.

MD: Yeah, I get it. If they work, it seems like a huge step forward for a dentist to be able to place things this quickly. But you always have to ask yourself: Is this about what’s convenient for me or is it about what’s better for the patient? And it may be different in the hands of the average dentist than it is for you.

DH: Again, I personally think the problem with some of the self-etching resins, and even the resin cements, is that the manufacturer can show us this great data, but what does it really do clinically in an environment on a live, vital tooth? I won’t name names, but there’s a product that is highly touted by the manufacturer as the best self-etching resin cement on the market. When zirconium oxide first came out, we had a lot of failures because we were using the wrong layering material, until it failed. So I cut off 45 zirconium oxide crowns utilizing this cement that supposedly bonded excellently to dentin. And every single one I cut off, the cement just peeled away in large sheets. There was zero bond. So we have got to ask ourselves: Are the materials that show great benchtop success on non-vital teeth done in a controlled environment giving us the same clinical success in the mouth in a very hostile environment?

MD: Right. And there is always going to be a disconnect between the two. I think you may be in second place behind me for the number of zirconia restorations cut off. I know I’ve cut off more than that. Some of the zirconia crowns I’ve cut off have actually been our new BruxZir® material. BruxZir is a monolithic zirconia restoration that, shockingly, dentists are prescribing in record numbers. Believe it or not, BruxZir actually passed IPS e.max in sales volume in November 2010. The ongoing wear studies at a couple of universities look encouraging, but you can imagine, having cut off zirconia-based crowns, what it might be like cutting off a full-contour zirconia crown! I have always thought this is something we need to talk about a little bit more. In fact, I remember you calling me once and saying, “Well, what if you have to do endo through one of these zirconia-based crowns?” And, at the time, we didn’t have a good set of diamonds. But now we’ve found some good diamonds to be able to cut those off. Are you using many zirconia-based restorations right now in your day-to-day practice?

DH: Lithium disilicate has replaced my zirconium oxide-supported crowns in the posterior. At one of my most recent lectures, a ceramist said IPS e.max has destroyed his Lava™ (3M™ ESPE™; St. Paul, Minn.) market, which makes sense! I still use zirconium oxide-supported crowns for posterior bridges and three units in the anterior. I do pride myself on trying to be metal-free as much as possible, and that’s the only option I have. But single units, whether it be full zirconium oxide or zirconium oxide-supported with layering ceramic, I rarely ever do those. I do IPS e.max.

MD: If you look at the history of indirect restorations in dentistry, of course cast gold was the first material out there — a monolithic material. Then, porcelain jacket crowns, which left a lot to be desired in terms of strength, but it was still just one material. Even back in the 1960s, there became this need to have something that was more esthetic than gold. We can talk about the current esthetic desires in Southern California, but even back in the 1960s there became a need to take a metal coping and fuse it to porcelain.

The PFM has been the workhorse of dentistry for the last 40 years. It’s driven American dentistry, this laboratory, and almost all laboratories, for that matter. But PFMs have always suffered from the problem of having porcelain bonded onto the metal substructure. And with this bilayered restoration, there is always a chance that something can go wrong. In fact, it’s rather amazing that a lot of the times nothing did go wrong with the bond between the two. But, by nature, a bilayered restoration is going to have more problems than a monolithic restoration. I think we finally saw that with the ceramic-bonded-to-zirconia market. Whether because of the coefficient of thermal expansion or the way people were fusing the two parts in the oven, there was going to be issues with compatibility and chipping. So, we’ve seen the same thing: IPS e.max, a monolithic material, and the monolithic BruxZir material introduced after it have destroyed the zirconia market. Again, the average dentist appears to be doing the same as you, at least in that respect.

You’ve always struck me as a guy who would probably have a CEREC® (Sirona Dental Systems; Long Island, N.Y.) machine in his practice. I’ve seen some of the artful direct composites and killer temporaries you’ve done, and you’ve always worked with the best ceramists to get great results on your final restorations. You really are as much of a lab tech as any GP I know, but I don’t know that you ever fully embraced CEREC. Do you have a unit now that I don’t know about?

DH: Actually, I do! But I’ve only had it for two weeks. I’ve done only four crowns. I was waiting for the camera to be better and for the software to be a little more intuitive before I took the plunge. It has been worth the wait.

When the 3M ESPE Paradigm™ Block came out several years ago, I was lecturing a lot on inlays and onlays. And 3M said: “Hey, we’ll send you a CEREC. Start doing the Paradigm Block and when you love it, you’ll talk about it.” Well, I hated the CEREC machine. It was so counterintuitive. After three weeks, I sent it back and said, “I’m not using this!”

MD: When was that?

DH: Maybe seven years ago? Whenever CEREC 3 came out. But now I’m looking at the software and looking at the camera, looking at the whole technology of digital impressions (which is obviously the future of dentistry), and it makes sense. You’re right in the fact that I do like to play with ceramics, but I’m not nearly to the level of expert ceramists. I can’t make a veneer or an anterior crown look the way they can. But the fact is we’re using monolithic IPS e.max in the posterior where I’m not having to cutback or layer because I want strength. I’m getting good esthetics with monolithic material. After all, the lab was just waxing and pressing or milling it to full contour and superficially staining it. I thought, why am I not doing that?

MD: I wasn’t praising you so much for veneers; I was complimenting your anterior direct temporaries. I would never take an impression and send it to you and say, “Hey, make my veneers.”

DH: I wouldn’t either!

MD: But I’ve seen what you can do on posterior teeth with direct composite, and it did seem like you are the kind of guy who would mill IPS e.max restorations in the posterior. You’ve always offered such great services to your patients. At Glidewell, we’ve now got six CEREC machines and probably 10 additional MC XL mills. I’ve got a CEREC AC in the operatory and I am convinced — here I am practicing in a lab, but regardless — I am convinced that one-appointment dentistry is better than two-week dentistry.

DH: I’ve only done four of these, so I’m not great at it yet. It’s like, how do I schedule it? One to two hours for a single unit? How long is it going to take me? But for the people who are great at it, I think it’s a huge advantage. I see this technology as an advantage for even a three- or four-day turnaround versus two weeks. Yes, we’re good at making temporaries; that’s what we’ve always done, and we’re good at it. But if we use this technology, we get reduced lab costs, improved turnaround time (whether that be 1.5 hours or three days) and total control.

Let me give you an example. On the third CEREC crown that I did, an IPS e.max crown, I decided to try it in and adjust occlusion in the blue block state before it was sintered. And the patient bit down and broke the crown! In the past, had I sent that crown to Glidewell and it was IPS e.max or IPS Empress, I would have made a temporary, sent it back, and you would have made me a new one. Well, the cool thing about CEREC is that it was in my library. All I had to do was go back to the library, click it again, and in eight minutes I had a new crown! That’s where there is a huge advantage. Or say you have a material that you put in and there is a marginal discrepancy. Instead of taking a new impression, you can take a new digital impression and do it in three minutes.

MD: I agree. That’s a better way to say it. I mean, it’s true: I do believe that one-appointment dentistry is better than two-week dentistry. But I also believe that three- or four-day dentistry is better than two-week dentistry. And I believe two-week dentistry is better than six-week dentistry! The shorter period of time between prep and seat the better because of bacterial leakage, teeth shifting and factors like that.

DH: And also the fact that today we are doing more conservative dentistry. The primary complaint with some of the crazy little single-cusp replacement onlays that we do is, how do you keep temporaries in? It’s a pain! If you plan to see this patient in three weeks, more than likely you’re going to see them twice in the next three weeks to re-cement the temporary. And if I can do it as either a single visit or get it back in two or three days because I milled it myself, we’re not going to have problems with provisionalization.

MD: Right, because patients don’t want to come in three times. And, frankly, you’ve blown any profit you might have made on that case after three visits.

It’s funny you mention reduced lab costs because here at the lab we are all for that. We want to reduce lab costs. I mean, of course we’d like to work with more dentists, but primarily we’d like to reduce lab costs. We’re getting ready to release, most likely at the Chicago Dental Society Midwinter Meeting, a digital impression system that we will sell to dentists for their practice. We’re looking at it as an IPS e.max/BruxZir wand, if you will. So, for monolithic restorations, a dentist would take a digital impression, which we realize is more work than a regular impression. To me, to take a digital impression if it’s not hooked to a mill is kind of silly, unless it’s going to save you money. And some of the other digital impression systems actually cost you money. It’s very difficult for you to get any ROI with those systems.

With the Glidewell system, we’re talking about taking a digital impression and sending it to the lab. Submitting the digital impression this way saves the dentist $27 on the cost of the restoration. There is no one-way shipping cost ($7 savings), no cost for impression material ($10 savings), and the lab discounts $10 because it can be digitally fabricated. So, we do want to reduce lab costs to dentists by cutting out some of the steps by making these model-free crowns.

You and other CEREC users have proven that model-free crowns can be made, and Sirona has 25 years of experience doing it. We know it works. Have you used many of the other digital impression systems, such as Cadent iTero® (The Cadent Company; Carlstadt, N.J.) or Lava C.O.S.?

DH: I haven’t used Cadent clinically. I’ve played with it chairside and it seems like one of the easier systems to use. I know a lot of laboratories prefer it. And I like the technology of the Lava C.O.S. system, but it’s very time consuming. We looked at it, we were going to buy it, and then we decided not to. As we talked to colleagues, some of my friends that are excellent dentists, a lot of them had sent it back. It’s not that it wasn’t accurate or that its technology wasn’t cool. But if it takes 40 minutes to take an impression, it’s not profitable.

You mentioned the cost savings of shipping, and that’s something that a lot of dentists don’t look at. If they say, oh, I only save $10 by doing that, what they don’t take into account is the money saved in outgoing shipping. They will also get a better turnaround time because instead of taking two and a half days to get it to you, the case arrives at the lab instantly.

MD: Exactly. I don’t like it when dentists are kind of force-fed technology or when dentists are told they are not doing great dentistry if they’re not using this technology. For example: On your polyvinylsiloxane impressions, do you perceive that you have a big problem with them day in and day out?

If you really looked at the weakest link in the chain of restorative dentistry, it would be the impression and the pour-up in crummy dental stones. But is that going to keep my restorations from lasting 10 years or more? No. We have more accurate materials today than we did 20 years ago, when dentists were doing gold crowns that were in the mouth for 40 years.

DH: Not a major problem, but I think that if you really looked at the weakest link in the chain of restorative dentistry, it would be the impression and the pour-up in crummy dental stones. But is that going to keep my restorations from lasting 10 years or more? No. We have more accurate materials today than we did 20 years ago, when dentists were doing gold crowns that were in the mouth for 40 years. So, I totally agree with you on that.

MD: That’s why I feel that if the digital impression system is not tied to a mill, where you can do same-day dentistry or three- or four-day dentistry and save nearly $20 per IPS e.max crown through a lab, what’s the point of going through the extra effort to do something like this?

What are you using for a diode laser these days? And I’m guessing you have a hard-tissue laser, as well?

DH: I use a diode every single day in my practice; we have one in each operatory. As far as hygiene, I personally think that use of a laser is standard of care. Dentistry as a whole will realize that in a few years.

The advantages of present-day diodes compared to the ones we used are that they are affordable and smaller. You can get a good laser for less than $5,000; all of a sudden, lasers are very affordable.

We’re also doing closed-flap osseous using an Erbium:YAG laser (AMD LASERS, LLC; Indianapolis, Ind.), which is very cool. So we’re performing crown lengthening without laying a flap, and we’re getting unbelievable results. Lasers, just like digital technology, are going to change the way we practice dentistry as they become more affordable and more dentists adopt the technology.

MD: Do you feel pretty confident with closed-flap crown lengthening? I know it drives some periodontists crazy — it’s hard to treat what you can’t see. But I have to say that biologic width violations are a real problem. As you walk through the laboratory and look at anterior models, you see interproximal violations left and right. You know the crowns probably look pretty good, but the tissue is purple interproximally because the prep outline doesn’t follow the gingival outline. Are you doing most of these in the anterior or posterior?

DH: I do it just in the anterior because I can tactfully feel the bone and make sure I’m not troughing or creating an artificial biologic width. Because posterior bone is thicker, I don’t do it. I refer that out if it needs to be done. I was keeping track of repercussions up to 2,500 teeth, and then I stopped, but we’ve had zero repercussions. I’ve done it in all my courses since 2004, and we’ve seen no problems. The cool thing is that unlike traditional crown lengthening, where a flap is laid and a diamond bur is used on the bone and then you wait 12 to 16 weeks, we’re prepping and impressing and provisionalizing on the same day that we do our osseous. We’re doing some fun, really cool things with that.

MD: Maybe in a perfect world every patient would be flapped and you’d see directly what you were doing. But the reality is that most of these cases have biologic width violations and dentists aren’t doing anything. They’re taking the old crown off and putting a new crown on. If anything, the margin gets dropped just a little bit further as the doctor goes in and cleans the cement off the prep, so the biologic width violation gets a little bit worse. I think you’re seeing good results because it’s a step in the right direction. It may not be 100% perfect, but maybe the patient wouldn’t have had it done surgically anyway. I think that some treatment to improve biologic width is better than no treatment at all.

DH: That’s right.

MD: You mentioned that you do closed-flap crown lengthening procedures during your courses. Tell me a little about the courses that you’re putting on today.

DH: The best source for those who are interested in where I’m going to be as far as a lecture or hands-on course is to visit davidhornbrook.com. Click on “Calendar,” and it will go through the things we’re doing. I still do a lot of full-day lectures across the country, and that’s actually ramped up because of all the new materials. People are obviously not getting trained in dental school on IPS e.max, prepless veneers and lasers. Now they’re hearing about it and getting excited. It’s good for me because I’m getting out there more, and I enjoy that aspect of my career.

We are still doing some live patient courses. As you mentioned, you went to my esthetic courses when I was teaching at LVI. Then I formed P.A.C.~live and the Hornbrook Group, which were also live-patient, hands-on treatment courses. Now we’re doing it through a series called Clinical Mastery. Doctors can go to clinicalmastery.com and see a list of the courses we’re offering, including occlusion courses and full-mouth and anterior live patient courses, in which dentists will bring their patients and their team.

We’re doing these courses primarily in Mesa, Arizona, at the new dental school A.T. Still University — Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health (ATSU). This is just a phenomenal dental school. It’s so different from where I went to dental school. The faculty is very embracing, very technologically advanced. In fact, I was talking to the school’s dean, Dr. Jack Dillenberg, and the school’s recommendation for posterior restorations is composite, not amalgam. The school only teaches amalgam so its students can get through the boards. It’s very interesting how different it is. The faculty is teaching veneers, implant placement, lasers. Students actually go through an entire laser curriculum. The students are learning some very cool things.

MD: That’s a real education! That’s pretty impressive.

DH: It’s not that I’m pushing this particular school, but if a doctor who reads this has children, relatives or friends who are thinking about going to dental school, I would look at ATSU. They only have one specialty program in the school — orthodontics — which means that graduating seniors leave dental school having placed an average of 15 to 20 implants because there is no periodontal program. The students are doing perio full-mouth surgery and impacted wisdom teeth — they’re just doing some really cool things.

MD: The better part of having no specialty programs is that there are no specialists there to tell them that this stuff is too difficult for them to do, and they probably shouldn’t try it. That was my dental school!

DH: Exactly, same with me. So we’re doing some cool things at ATSU. Again, dentists can find out more about those courses by visiting my website davidhornbrook.com or clinicalmastery.com.

MD: I want to close by telling you a story. I’m not sure if I’ve told you this before, but when we were together at LVI, I brought a patient …

DH: I remember the case! When you left retraction cord in there?

MD: Whoa, whoa, whoa, I didn’t leave retraction cord in there. What happened was that the two IPS Empress crowns on teeth #8 and #9 were deeply subgingival. We weren’t doing much soft tissue recontouring back then, and certainly no hard tissue. But that’s really what this case needed. You said, “Let’s put some retraction cord in to contain the gingival fluids when we bond these crowns into place.” Well, I guess I was a little sloppy. I pulled the retraction cord out from tooth #8 after curing the cement, but when I went to pull out the retraction cord on tooth #9, I had bonded it into place. I tried to get it out and you tried to get it out. The good news is that it was size 00. The bad news is that it was black, and I’d bonded it between the crown and the tooth. You could see it through the patient’s thin tissue, and you said to me: “Congratulations. You are the first dentist in history to do an all ceramic crown that has a gray margin like a PFM.” I’ve always been proud of that.

Later, that patient went snow skiing with his wife and she fell getting off the lift and smacked him in the face with a ski pole. And he called me in a panic and said, “My wife broke one of my front crowns off.” I asked which one and he answered, “The one on the left (tooth #9).” I thought to myself, Hallelujah! Then he asked if he should look for it. “Hell, no!” I didn’t want to have to explain what the black string was hanging off the crown.

So, your course and that experience were really instrumental in teaching me to pay attention and really do things right. Dentistry has been a learning experience for me, with this average set of hands I have.

David, I want to thank you for being there every step of the way and being very generous with your time, especially for an interview like this.

DH: Thank you, Mike! It’s always great to hear your voice because I haven’t talked to you in so long. You certainly have done so much for our profession, and I consider you a mentor, a great friend, and I appreciate being asked.

MD: That’s right. And I do still maintain that you are the most well-rounded educator out there. And that’s why if you’re going to give your blessing to do closed-flap crown lengthening, I’ll feel a lot better when I do it tomorrow, if it’s one of those situations you mentioned where it is in fact indicated.

Dr. David Hornbrook is a leading educator in esthetic dentistry. For information on his upcoming lectures and hands-on courses, visit davidhornbrook.com or clinicalmastery.com.