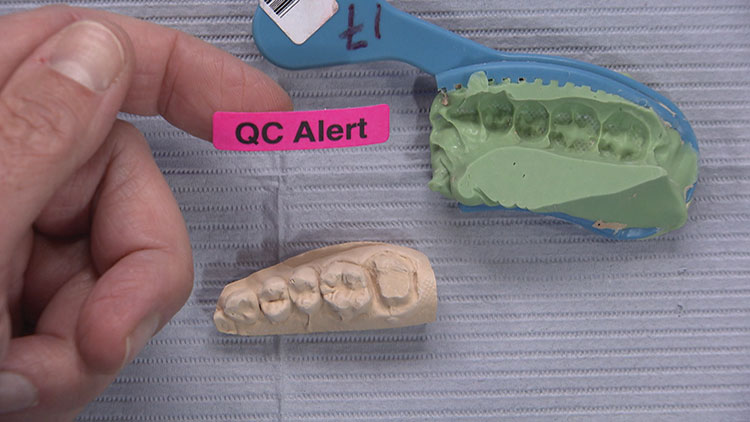

QC Alert: Avoiding Dreaded Remakes – Case of the Week: Episode 85

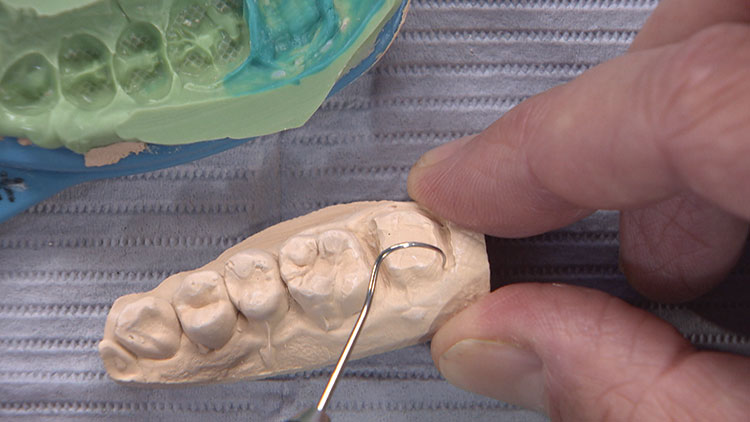

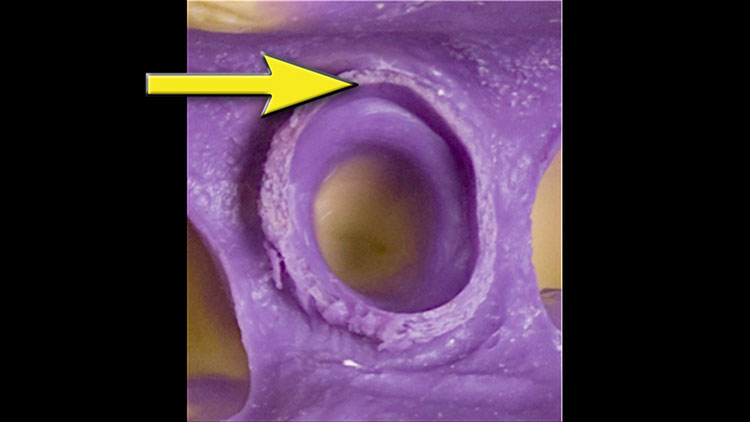

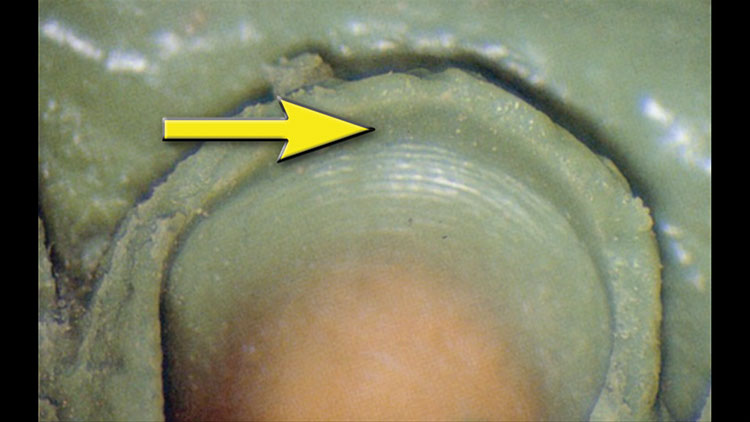

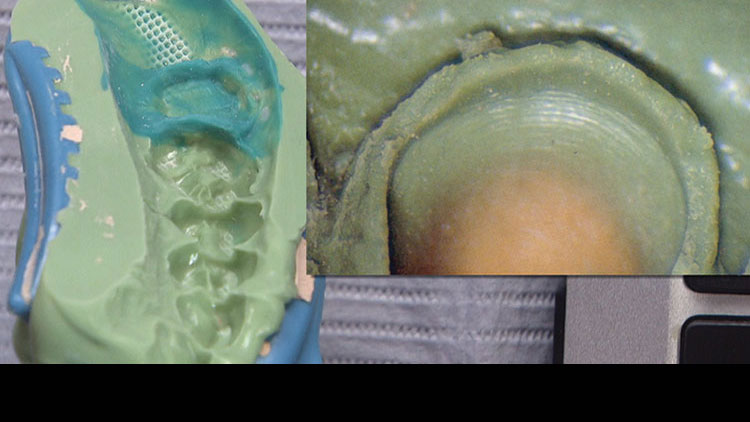

We’ve got a great Case of the Week for you from Episode 85 of “Chairside Live.” It’s from a dentist who is actually a pretty big account here at Glidewell Laboratories, and she’s a really good dentist. She had been frustrated with some of her results, and I think they have to do with the impressions. I wanted to take some time to present alternative methods that might give her better results. They might be a little more time-consuming than those you’re doing now, but they’re completely worth it if you can eliminate remakes and adjustments in your office, and avoid having to send things back to the lab. So, let’s take a look.