One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: Interview with Jeffory Wyscarver

Jeff Wyscarver is a registered polysomnographic technologist (RPSGT) and president of DDME (ddmeonline.com), a company that brings sleep lab technology and services to the dental community. I met him when he visited our lab to share some interesting research and products related to a disorder he called "sleep bruxism." Bruxism is a familiar term at the lab because we make bite splints and nightguards to protect patients’ teeth. We also make and sell several appliances to treat sleep disorders like snoring and sleep apnea, such as the Silent Nite® sl and TAP® 3 Elite. But when Jeff came to talk to us, it was the first time we had heard anyone connect these sleep disorders with sleep bruxism.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: This is going to be the first time many of our readers see the term "sleep bruxism." Can you explain a little bit about what this is?

Jeff Wyscarver: The beginning for me with regards to tackling sleep bruxism came when I started talking to a number of dentists and notable pain clinic specialists who had a desire to be able to measure jaw activity while a patient slept. There’s quite a bit of information about waking jaw activity, but there’s not a lot of good or useful information about the jaw activity of a patient while asleep. So I went about figuring out how to provide that type of information to dentists so they could make more informed decisions when they’re prescribing any type of appliance, whether it be a snore appliance, an appliance to keep the back teeth from finding each other during the night, or a sleep appliance. We introduced a device to dentistry that allowed us to measure the airway and the jaw activity while a patient slept, and this struck a chord with many clinicians.

MD: I’m familiar with the types of devices that can be worn for a sleep study, whether it’s performed overnight in a sleep lab or by the patient at home. How does this device differ from a typical sleep study?

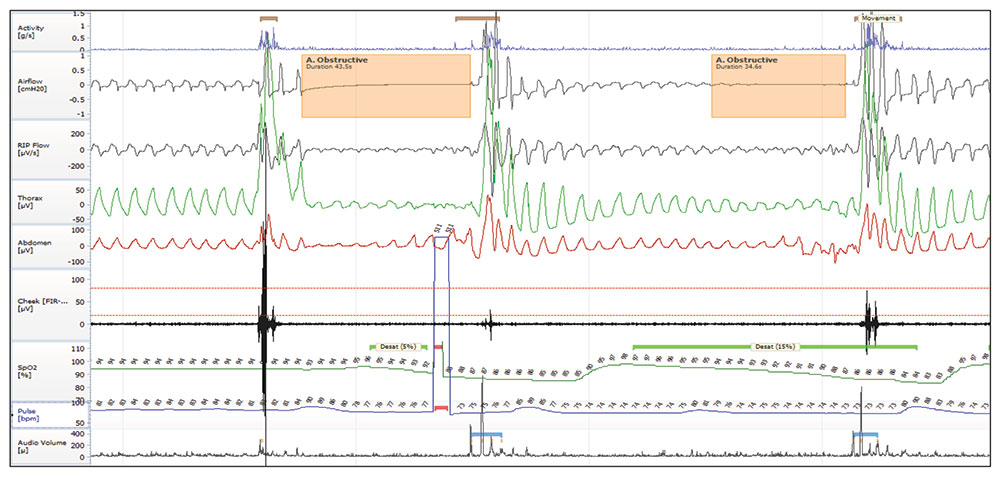

JW: The fundamental difference is that our approach is from the dentist’s perspective and not from the sleep lab’s perspective. For example, I’ll describe a sleep study. Many people are surprised to learn that every full polysomnogram (PSG) done in a sleep lab collects jaw electromyography (EMG) data. So the data that we need to help dentists make some of the more informed decisions about patient treatment is always measured, but because the medical community doesn’t necessarily tackle bruxism directly unless requested, that data is essentially ignored and used for another reason. When we started helping dentists, we learned that the jaw EMG was clearly in their wheelhouse. They really are interested in and educated on the jaw. So we added that to our procedure. That differs from the other devices in that the other devices are primarily used to diagnose patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Our device does that, too, but it also tells the dentist what the jaw is doing in relation to the airway. This data is not necessarily collected for the purpose of diagnosing the patient with obstructive sleep apnea (in fact, DDME provides Board-Certified Sleep Physicians for that purpose), but it’s good for a dentist to understand what the airway is doing along with the jaw. I think the primary distinction is that jaw activity is measured on the same time axis as the airway. There are a lot of devices that measure the airway, but when you add the jaw EMG into that time axis, it seems to add quite a bit of useful information for the dentist.

MD: If they’ve always measured EMG data in sleep laboratories, I guess that means they run some of the electrical leads to, say, the face outside of the masseter muscle, for example?

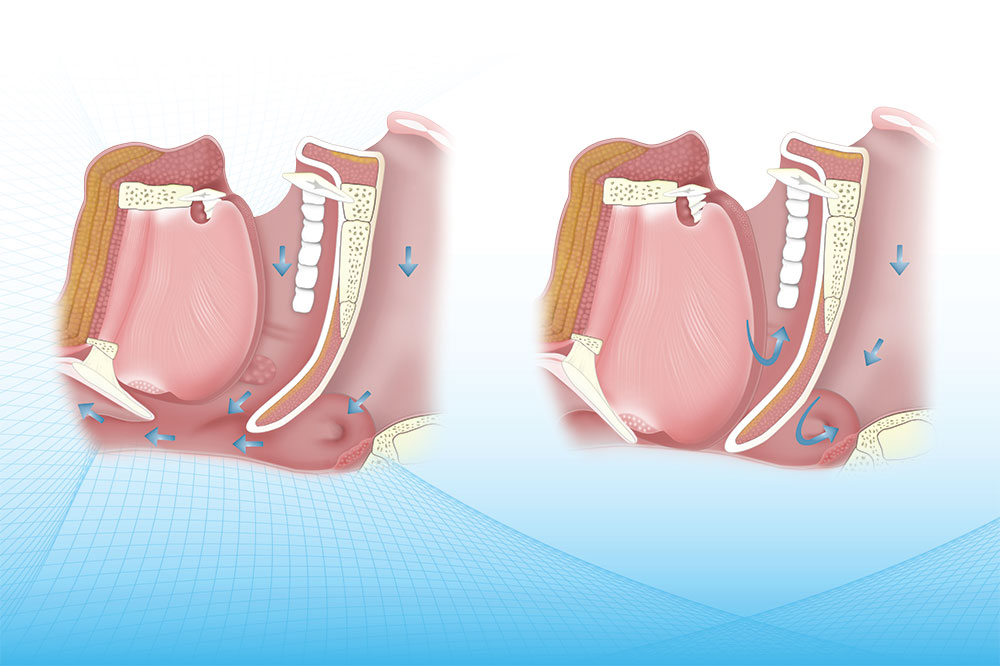

JW: The jaw is, in my opinion, the most fascinating muscle on the body, simply because it’s a very elegant design when you consider what it does and how it supports the airway. Sleep studies actually measure the chin most often because of that complex and intimate relationship with the jaw. The jaw has a unique measurable function during REM sleep. That is to say, during REM sleep, the brain suppresses skeletal muscle activity, so you don’t act out your dreams. As you measure the chin through REM sleep, jaw activity goes down to its lowest level, and the tonic baseline goes back up during non-REM sleep and waking. Sleep labs measure that muscle simply because it provides unique information as to when a patient is actually in REM sleep.

MD: Interesting! So they’re actually using the data to determine REM sleep, and they measure on the chin, not the masseter. I know you have decades of experience in this field: Looking at the incidence of bruxism and obstructive sleep apnea occurring simultaneously, do you see a definite relationship between the two?

JW: In many cases, much more than I imagined, there is a correlation between parafunctional or unusual jaw EMG activity and the presence of obstructive sleep apnea. The reason for my opinion on that is, I’ve been collecting data in conjunction with the dentists that I work with, and it’s unusual not to see some amount of chin EMG activity in the presence of apnea. Getting back to the uniqueness of the jaw musculature, I have learned that the jaw has a direct connection to the arousal response from other muscles in the body. When an arousal occurs, the jaw participates in that event. It could be airway resistance, crescendo snoring or any other respiratory event, such as a hypopnea (abnormally slow or shallow respiration) or apnea (cessation of respiration). Bruxism in the presence of disordered respirations is closely tied to what we call the "autonomic response," which is when the body senses something and changes the physiological levels in response. The heart rate goes up, EEG levels change and the jaw fires. The jaw participates in the arousal response. There are a variety of theories circling that response, and I think more data needs to be collected. But the jaw is unique in that we often observe it participating in the arousal response.

MD: That’s amazing. I don’t want to read too much into this, but is the activation of the jaw as part of this arousal response the body’s best way to wake somebody up and get them breathing again?

JW: I would say that the effect of the arousal response often is that the airway is preserved or recovered from an airway issue. But I don’t want to make the conclusion that the body tugs on the trachea to make it patent as a result of an apnea, because I think the jaw would tug on the trachea if there was some other response that it needed to respond or input to as well. We have also seen a patient breathing normally, and then an abnormal jaw EMG event occurs and produces a series of respiratory disturbances. In this type of situation, the airway is reset by an idiopathic bruxism (no observed cause). Essentially, the airway is reset, but not for the better. It is similar to when you’re holding your breath, and the body says, "Oh, I need to do something," and it activates a system. One of the elements of that system is the jaw. Due to the elegant design, you activate the airway muscles, which changes the shape of the airway. If you happen to be in a hypopnea, and you have an arousal response, it’s very likely that your airway will recover.

In many cases, much more than I imagined, there is a correlation between parafunctional or unusual jaw EMG activity and the presence of obstructive sleep apnea.

MD: You said the vast majority of patients you see experience bruxism and obstructive sleep apnea occurring together. What percentage of people that do a home sleep study with your device would you say suffer from bruxism, but not obstructive sleep apnea?

JW: That number is higher than I expected, and let me give an explanation as to why I believe this to be the case. Many of the dentists we work with aren’t necessarily working with patients on their apnea or snoring, but rather on TMD issues. When they learn the capability of the Bruxism Monitor (DDME Inc.; Las Vegas, Nev.), they do testing on patients that they know to have a jaw issue. They might have a jaw pain complaint, or jaw clicking, or there may be worn teeth involved. So there’s a very high likelihood that that patient already suffers from some type of bruxism as an isolated disorder. I think the key take-home message here is that bruxism is a disorder in and of its own, and it can have no apparent cause. Treating it as an independent disease is a complicated process. Again, there’s a very high likelihood when we get that jaw issue patient that we see bruxism as its own disorder. I think a lot of people are curious as to what percentage of people in the general population are running around out there with just bruxism issues, but the data is fairly weak there; the percentages are widely spread, so I can’t answer that question.

MD: You mentioned the Bruxism Monitor, which is the name of the device your company distributes. Can you tell me a little bit about how it compares to some of the other devices out there, maybe in terms of size, comfort and what it measures?

JW: When we decided to go into dentistry, we started out by asking, "What is the best sleep device out there?" We went through and evaluated a number of devices. With the selection criteria that we had, we put a premium on ease of use. The reason for that was we knew we were going to go into a non-sleep-trained environment, and we needed to be able to collect good data on someone who has never done a sleep study before. We evaluated a number of units, and there were a few units that made it through the ease-of-use criteria, and the Bruxism Monitor was one of them.

Another category that we had was cost per test. This is where the Bruxism Monitor separated itself from the devices that were left. So there were a few devices that passed the ease-of-use category, but the other devices that were still in the running were actually quite expensive to use per test. The Bruxism Monitor cost per test was about half that of the remaining devices on our list, so it scored high marks on cost per test as well.

The last selection category we evaluated was clinical yield, which is a term we use to describe how much cost and effort it takes to get effective, usable data. The Bruxism Monitor scores very high marks there. It has a number of internal design features that we don’t necessarily talk about much, which give the device a very high clinical yield. That is to say, the data collected can be used to improve the decision the dentist makes. We had to make sure that if there was a feature in there that it wasn’t just a feature. It was important that what that feature brought the clinician was valuable. When we passed the devices through the three-phase selection criteria, the Bruxism Monitor won out.

MD: Well, it sounds like you did a lot of research, and I certainly agree with the qualities you looked for in a unit. Dentists want operational affordability, and the patient doesn’t want to pay a lot to do the test either. So it sounds like your device measures muscle activity to come up with an idea about the bruxism, and it also measures hypopneas and apneas. Is it also able to record snoring or measure the volume of snoring?

JW: Sure, it does. One of the features that improves the functionality of the Bruxism Monitor is that it records the audio of the sleep study. That’s valuable and effective information for two reasons: First, you can play back somebody’s snoring if you have a patient who says they don’t snore that badly. When you play the audio back, it’s hard for the patient to deny; it burns through the denial very quickly.

Another reason is that when you’re measuring the jaw and the jaw muscle, there’s been a fairly stringent diagnostic criteria set by research done using full PSGs. One of the features that the Bruxism Monitor has is a two-channel amplifier. When we use one of those channels to measure the jaw we see a big EMG burst, which is great. It’s compelling data. It can be counted. It’s easy to score. So for a number of reasons, that EMG signal is very valuable. But in the literature, the diagnostic criteria is that you either need to have a corresponding audio or video record that occurs in conjunction with the tooth grinding. Because we actually record the audio signal, and we don’t use a separate technology similar to most of the other devices, we actually catch the sound of the teeth clenching. To my knowledge, we have the only device on the market that can detect an occlusion using the EMG burst in a corresponding audio signal.

MD: What does that sound like?

JW: Well, it’s a low, grinding noise, and it’s actually painful to listen to if you imagine how much force it takes to make that noise. If you and I were to sit here and grind our teeth, it would be a fairly silent occurrence. But when you listen back to this grinding and you hear the teeth crunching, just imagine how much force it takes to produce that noise.

MD: I guess that could be interpreted to mean that when you’re asleep some of those protective reflexes are down, and you’re able to squeeze together harder than you ever would while you’re awake.

JW: Absolutely. There are a couple of unique attributes of the collected data. For one, it’s easy and inexpensive to get to. You don’t have to send a patient to sleep lab to get it. We’re collecting a lot of data in the home, and we’re uncovering some interesting information. If we ask a patient wearing a Bruxism Monitor to grind their teeth as hard as they can, we’ll gain a calibrated measurement in microvolts that records that strongest teeth clench while awake. Then when that patient goes to sleep, it’s not unusual to see a dramatic increase in that patient’s bite force during the night. In fact, I would say that in most people that we’ve measured, their bite force is anywhere from 50% to 200% higher while they’re asleep than their maximum force when they’re awake. I don’t necessarily have an explanation for this.

MD: So we can measure how loud the snoring is, the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and the bruxism. How do you work all three of those factors together? And how do you figure out what type of category the patients belong in?

JW: I’m going to step back just a second and explain my perspective. Coming from a sleep lab in the medical community, we approach medical conditions in a certain way. Now that I work with dentists, I can’t help but impose my medical diagnostic training on this particular problem. What we came up with, for a variety of reasons, is what we call a disposition matrix. We encourage our dentists just to take the measurement and know what their patient is doing. When you take the measurement, we have a snoring number; the Bruxism Monitor reports snoring in decibels. If the snoring is above a certain amount of decibels for a certain amount of time, you say "yes" to snoring. If the patient has an AHI above normal — an AHI above five — you say "yes" to apnea-hypopnea index. If the patient has bruxism, and it crosses the mild-to-moderate level, you say "yes" to that. At the end of the checklist, or the disposition matrix, the dentist essentially has a map he or she can use to guide the patient’s therapy.

I’ll give you a couple of examples of how the disposition matrix works. Let’s say that a dentist specializes in treating patients with snoring. We believe, as a lot of people do, that it’s difficult to tackle snoring without taking into account the possibility that the patient also has obstructive sleep apnea. So if the dentist just wants to treat the patient for snoring, and they say "yes" to snoring because the patient’s frequency of snore and their decibels of snoring are above normal levels, then great! So then the patient definitely does snore, and you have objective evidence that says that. Let’s say the patient also has obstructive sleep apnea, and you have to put a check there. Now that dentist has to make a decision. Do they just put in a snore guard or snore appliance? Or should they have the patient diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea? I think most would agree the prudent decision would be to manage the apnea, and in the course of managing the patient’s apnea, the snoring will be managed. It’s not necessarily bad news for the dentist, but it’s an example of using efficient and effective information to make a good, sound clinical decision.

MD: Let’s say that the patient also coincidentally has bruxism, but maybe whatever testing device the dentist used gives no indication of whether the patient is bruxing during these obstructive sleep apnea events. When the doctor simply puts in the sleep apnea device, doesn’t it treat the bruxism in a sense because now there’s something in between the teeth?

JW: That certainly is the case, and it’s a perfect example of how our diagnostic system works. So there are two additional outcomes that are critical for the treatment that are unique to our device. One is: Are you going to manage the airway? If so, how do you know it’s necessary? Let’s say you have the patient diagnosed with apnea and they also have bruxism, so you put the appliance in. What’s the next step? Well, you take another measurement. You see the residual apnea, if any. If there’s residual apnea, you titrate the apnea appliance a little bit, and then you also get a sense of whether the bruxism goes away or not. As you titrate the patient using the sleep appliance and you take two or three measurements during the titration process, by the end of the titration process, you’re going to know whether the patient is breathing well and the status of their bruxism. I can say from personal experience that about half the time, the bruxism does not completely resolve. Sometimes it persists, and sometimes it doesn’t. I think what the clinician can do is decide how they want to approach this. For example, the clinician may want to get a little more vertical with the sleep appliance to see if it prevents the occlusion from happening.

MD: Interesting. Everybody seems to agree that continuous positive air pressure therapy (CPAP) is still the gold standard for treating moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). If a physician’s patient goes in for an overnight sleep study and is found to have severe OSA, or maybe even moderate OSA, and the physician puts them on a CPAP unit, do you feel like that treatment completely ignores the bruxism aspect of it?

JW: CPAP is a treatment for a medical condition, and the medical community by and large has handed off any type of issue related to bruxism over to dentistry. But I don’t believe dentists are aware that a hand-off has occurred. When I started getting into dentistry, many of the dentists I talked to about bruxism didn’t know that it was common for the medical community to essentially ignore bruxism as an issue. So to answer your question: Yes, the treatment of apnea using CPAP does ignore bruxism. The question is: What percentage of bruxism occurs as a result of apnea, and in what percentage of patients does bruxism occur for other reasons? In the percentage that occurs as a result of apnea, if you resolve the apnea, then yes, CPAP does alleviate bruxism. But that’s not measured in the medical community. Dentists would be interested in that, because even if you have a CPAP patient, when you use the Bruxism Monitor and take a measurement, you will see what their jaw is doing and that they may need some help in that area.

MD: You probably think it’s criminal that we’re not taught about any of this in dental school. Dentists graduate from school and are kind of left to decide if they want to get involved in a field like this. From your perspective, what’s the best way for a dentist to gain some knowledge in this area to get started treating these patients?

JW: I would say the vast majority of dentists who educate themselves in managing patients with apnea get their training after they graduate. There are a number of academies, study clubs and information sources available out there. I have a certain amount of compassion for dentists getting into this field, as there are some headwinds there, and a lot of the headwinds, I think, could be avoided. I’ll say it that way.

I’ll step back and tell a personal story of how I made the decision to go from medical to dental. One of the things that I found very frustrating in working and running very large sleep labs for many years, and even in designing sleep diagnostic equipment, was the fact that we know that it’s not difficult to diagnose somebody with sleep apnea, especially when the patient is otherwise healthy. I always found it fascinating that when I was running sleep labs, we would have case conferences. I would say that 90% of patients that we saw had sleep apnea, and as part of diagnosing sleep apnea, we would have a pulmonologist, a psychologist, a psychiatrist, a neurologist, somebody like myself and the director of the sleep lab all sitting around deciding what to do with a patient that had an AHI of 30. It’s a fairly simple decision, so I was frustrated in medicine as to how difficult we made diagnosing people with obstructive sleep apnea. When I made the move to dentistry, I decided to make this as simple and direct as possible. When you have a relatively healthy patient, and they have complaints of snoring or pauses in breathing, I think that a dentist can be the quarterback at managing that patient.

Now, it’s important to understand that I didn’t say diagnose the patient. I said managing the patient’s process of getting treatment. Getting back to the question about training: It is not difficult to manage the diagnostic process. It’s not difficult to identify the patient that’s a candidate to be managed, and it’s really not difficult to get the patient into therapy, whether with CPAP, oral appliance therapy, surgery or any of the other options. What I say to dentists is: "Keep it as simple as possible. Make sure you don’t do studies on patients you shouldn’t. Make sure the patients that you identify are good candidates for the therapy that you can offer, and if they’re not, you need to find a place for them." There is some training involved, there’s picking the right oral appliance, there’s getting good information on the patient that you’re treating; and then from that, you’re able to make some very good decisions and manage the patient’s airway.

I’ll make one other comment about dentists managing healthy patients that have the possibility of obstructive sleep apnea. In the medical community, we’re very much event-driven. By that I mean that we wait for the patient to have an event to respond to it. We treat the symptoms, and we help them through the event. Dentistry’s model is different. Dentists want to see the patient over and over and over again. One of the things that you learn early when you’re treating patients with OSA is that it’s a chronic condition and requires a lot of follow-up. Follow-up is built into the dental business model. That’s not something they have to change or achieve. I think that’s one of the reasons that dentists are very well positioned to manage people who are healthy and have apnea complaints.

MD: I like what you said about dentists being able to be the quarterbacks of this process and coordinating the treatment, but leaving the diagnosis to the physicians. What do you find the learning curve to be like for dentists when they get into this field?

When you have a relatively healthy patient, and they have complaints of snoring or pauses in breathing, I think that a dentist can be the quarterback at managing that patient.

JW: Well, there are two basic learning curves. There’s the hobbyist curve, which is the dentists who, from time to time when somebody brings it up, will want to learn how to help patients with apnea complaints. The hobbyist curve is very slow and extends over a long period of time; they might take one or two courses a year. At the end of the first year they might feel comfortable, and then they’ll start treating patients who bring a snore complaint, for example. The other curve is the dentists who decide that treating people with complaints is going to be central to their practice. They concentrate on their education and the learning curve is very steep. So there are two curves there. The dentists who have decided that sleep is going to be the focus of their practice are ready to go very quickly. The skill of managing patients with apnea starts with education and is made very efficient with experience. The reason that the hobbyist curve is so slow is that experience in treating apnea patients comes over a long period of time. The problem becomes that the dentists don’t have the ability to build up the experience that they need.

MD: That makes a lot of sense. If dentists reading this want to get more information on the Bruxism Monitor or the services your company provides, where is the best place for them to go?

JW: We have a website at ddmeonline.com, where they can find information on our products and services. They can also email us at ddmeonline@gmail.com or contact me on my cell at 951-496-6126.