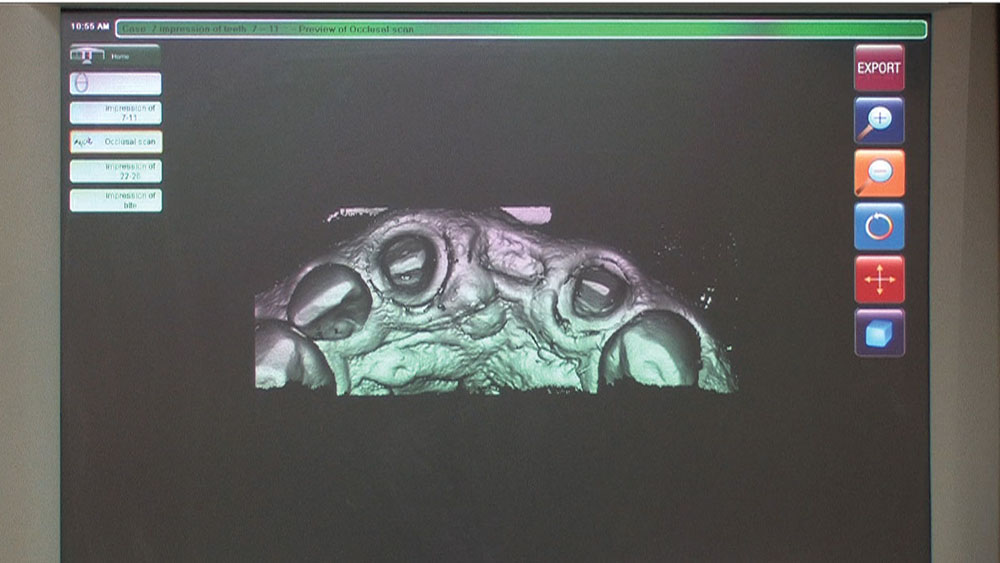

Photo Essay: Contouring Technique for an Existing Ovate Pontic Receptor Site

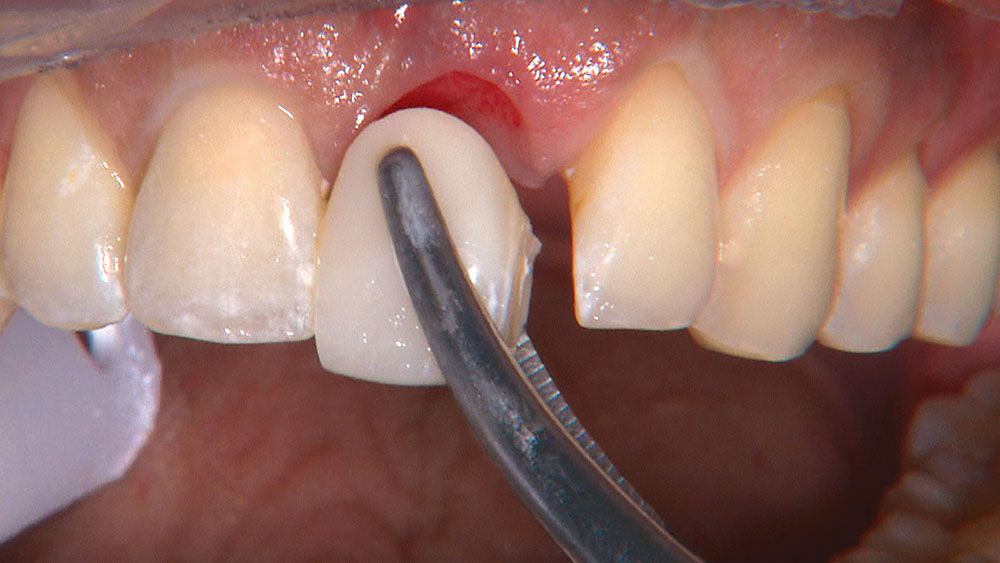

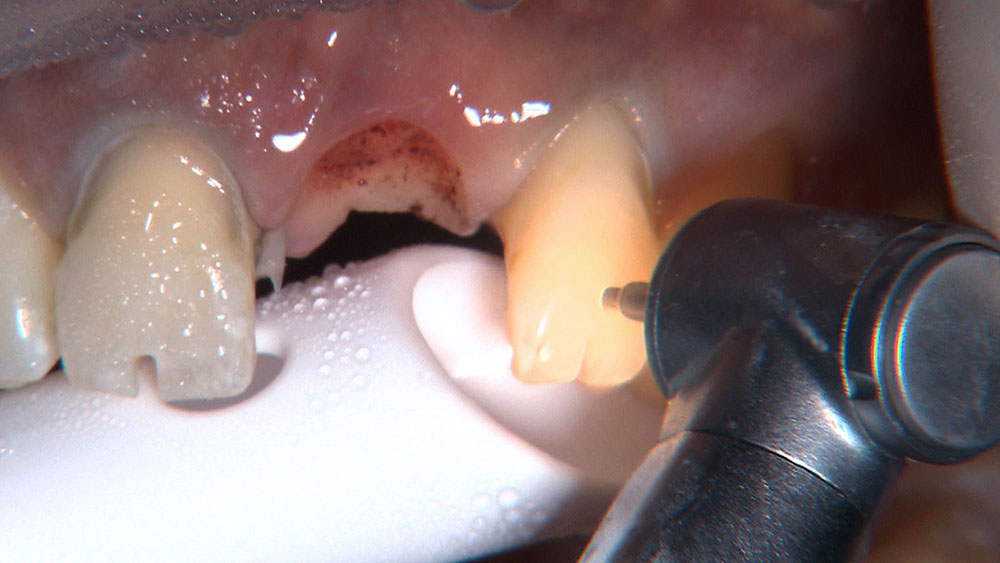

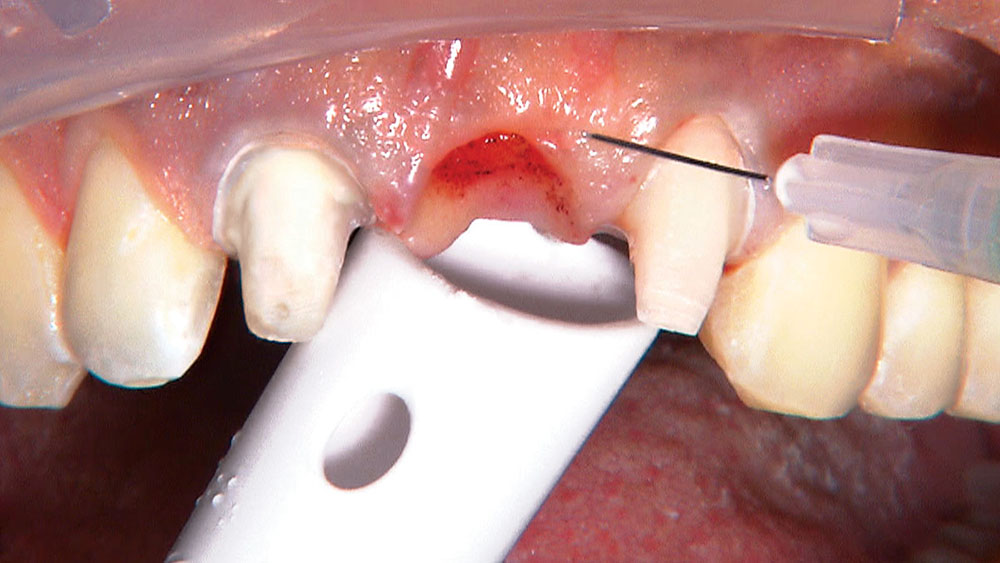

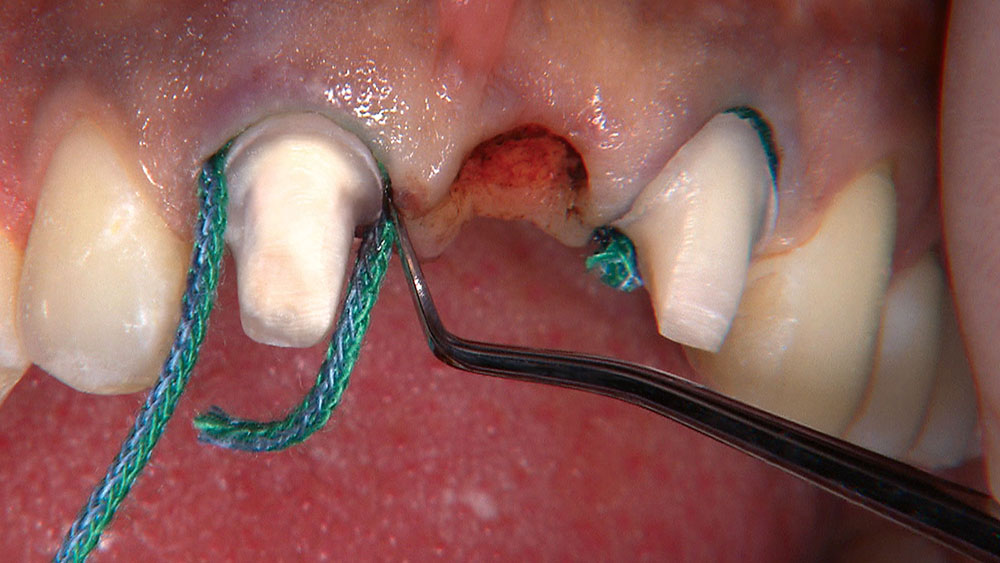

Despite the increasing availability of dental implants, many patients choose to close edentulous spaces with fixed prosthodontics. When using fixed bridges to replace missing teeth, the dentist should aim at achieving the most esthetic result possible, especially in the anterior region. In the case that follows, the patient already had a Maryland bridge with an ovate pontic receptor site, but it was a little shallow on the facial. He was requesting a replacement prosthesis to fix the recurrent debonding of his resin-bonded bridge. Because I would be replacing his existing bridge, I decided I would also redefine the ovate pontic receptor site that was created when the bridge was first placed 15 years prior.

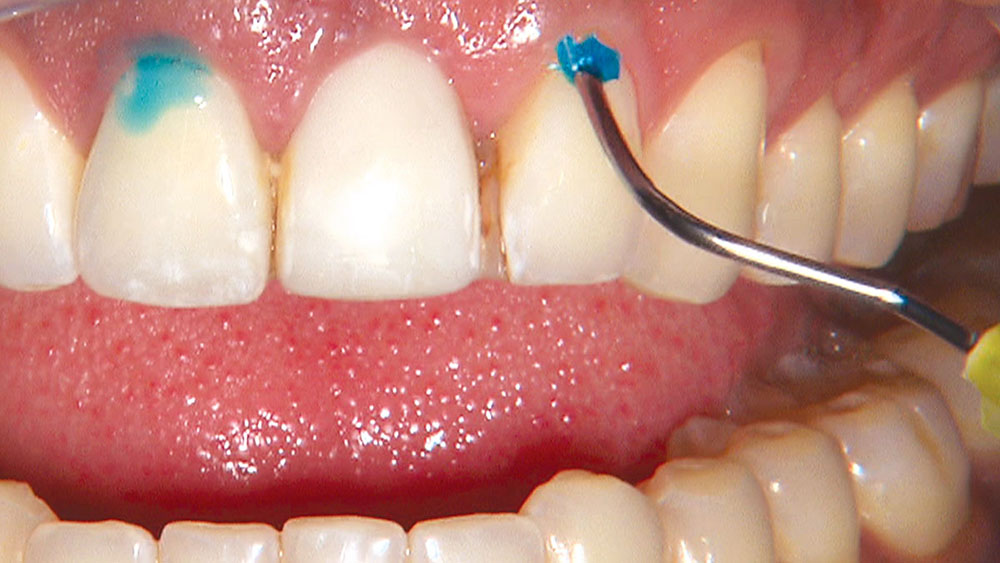

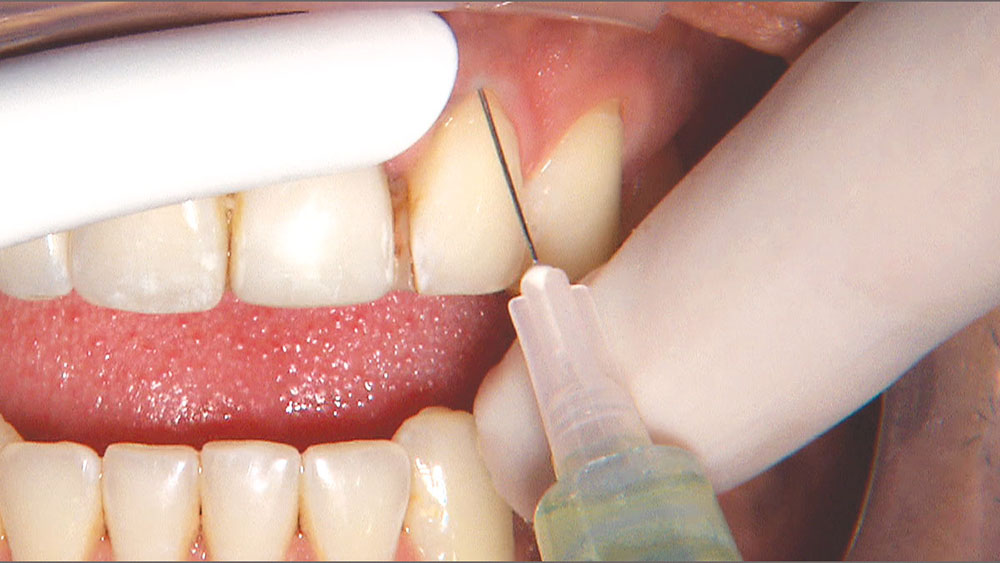

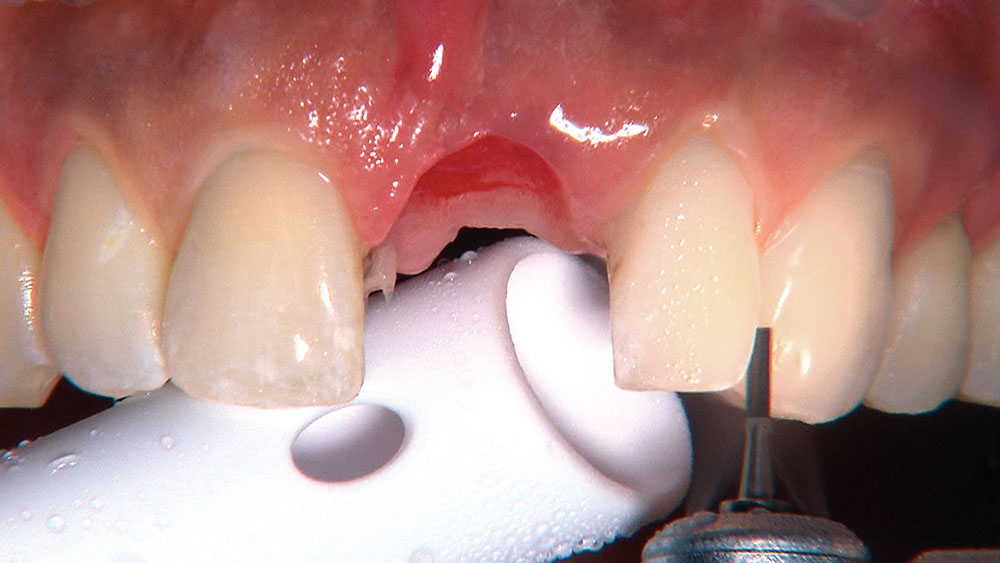

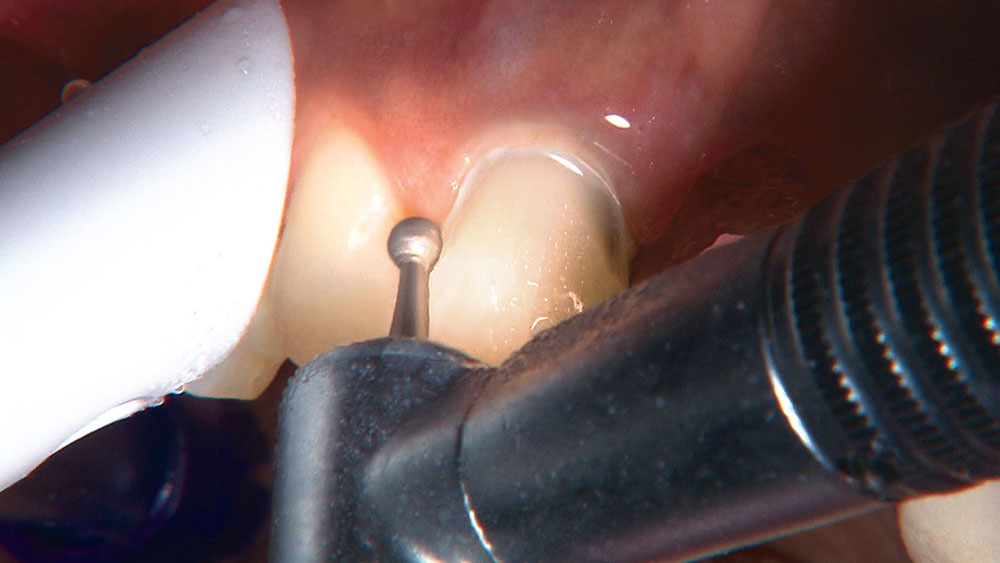

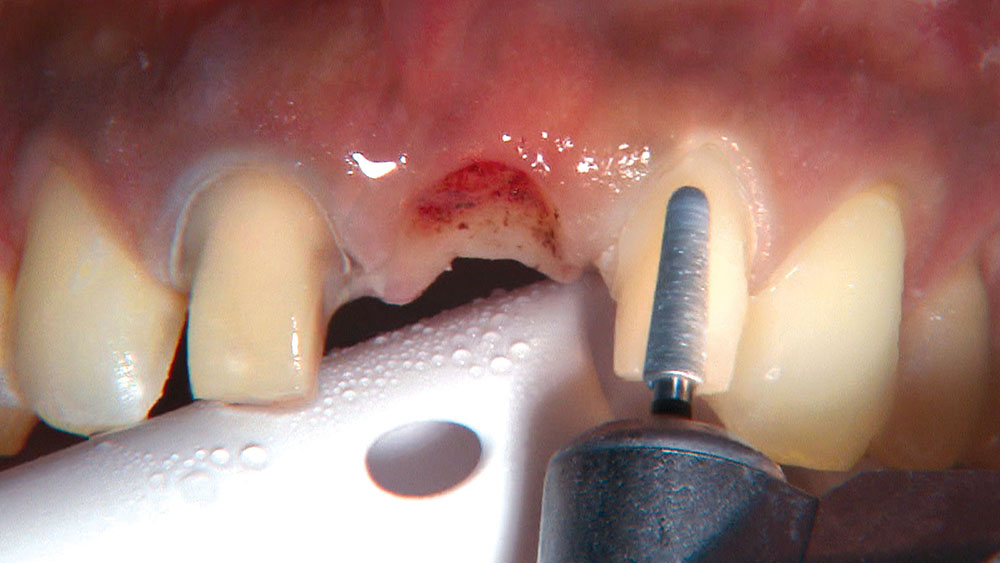

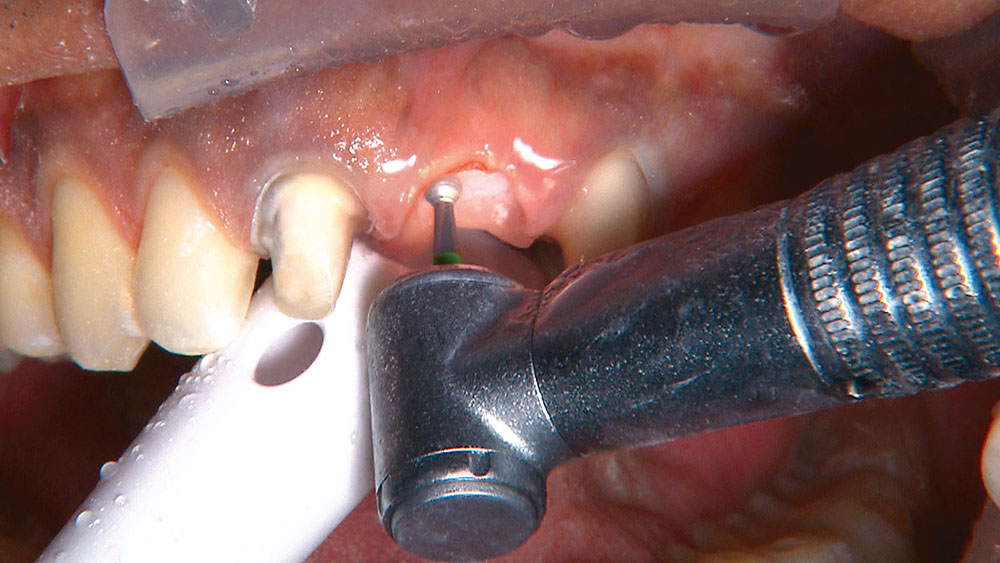

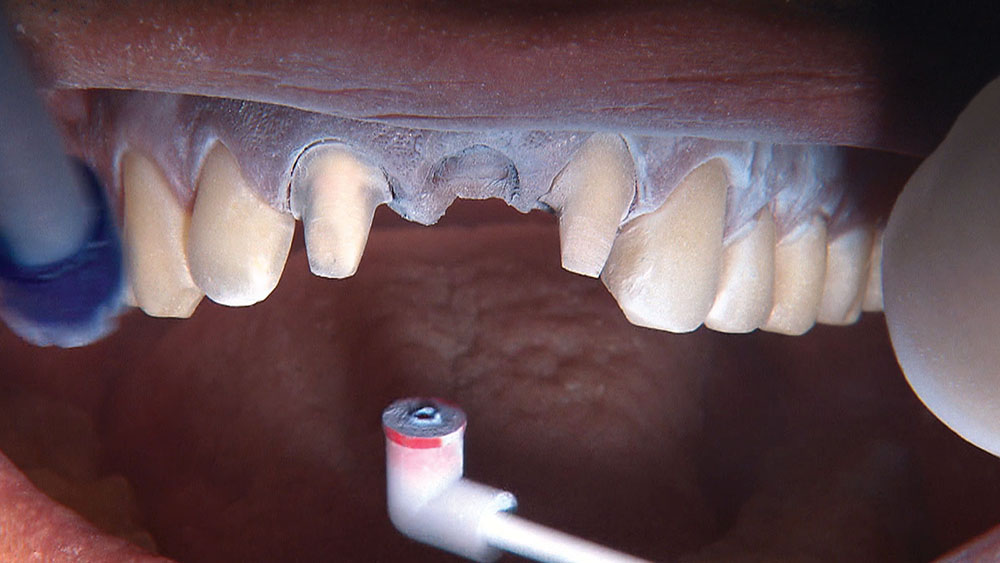

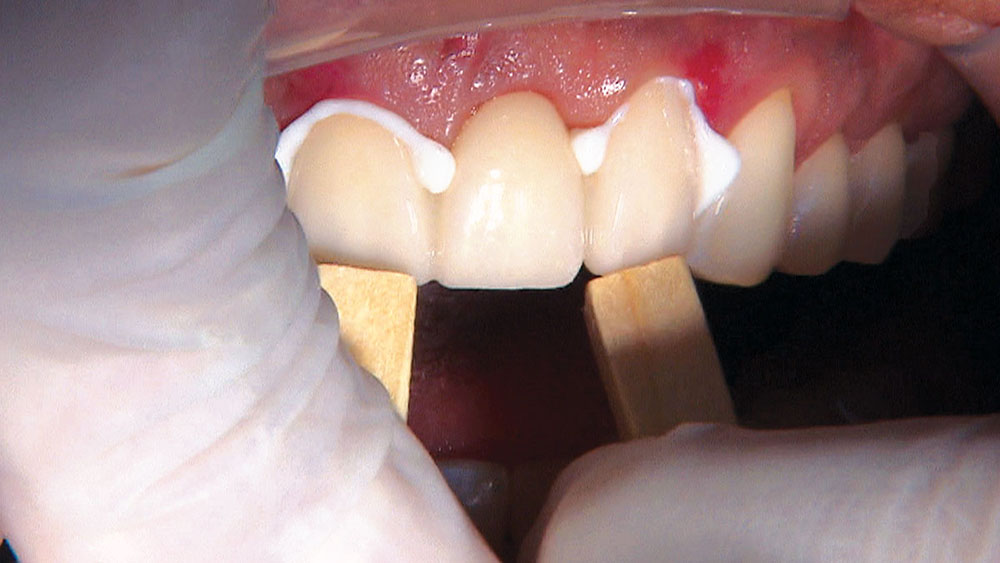

By angling the tip of the syringe toward the tooth as I dispense the gel, I am able to get some of the topical anesthetic into the sulcus.

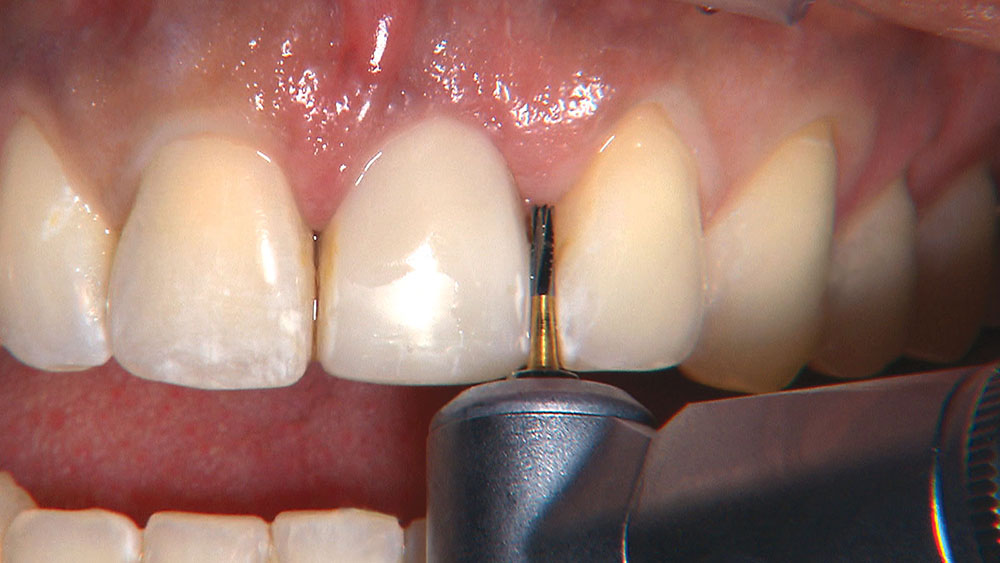

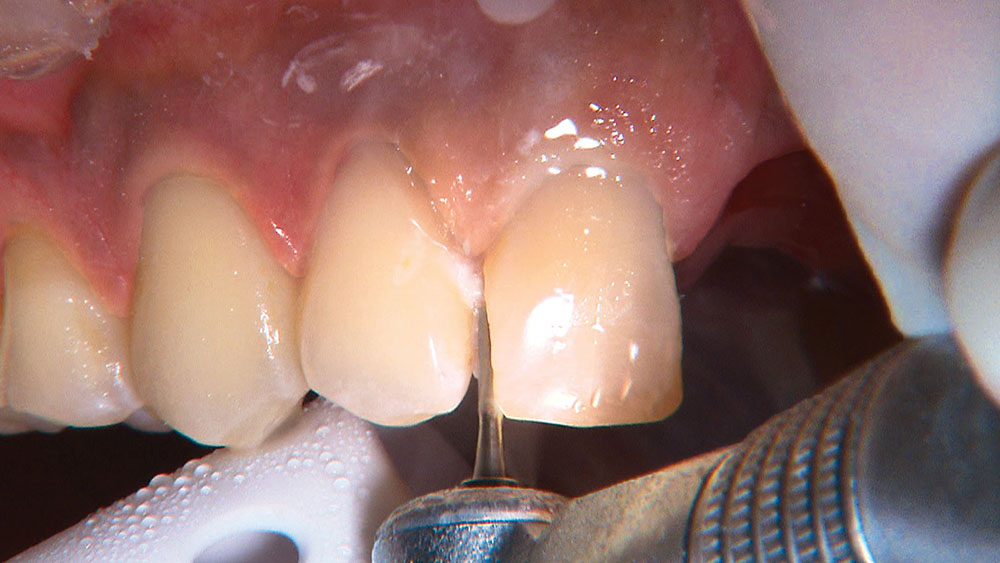

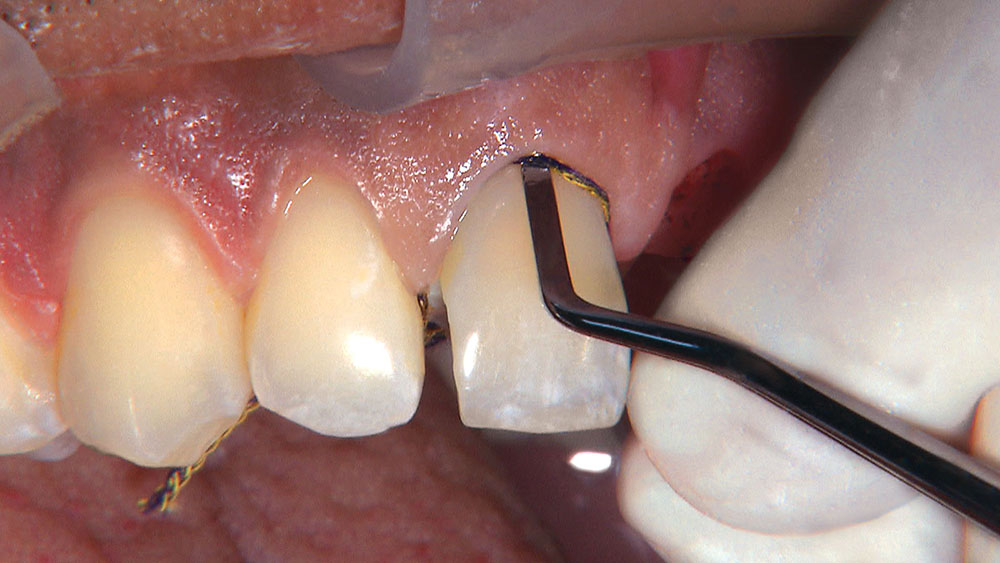

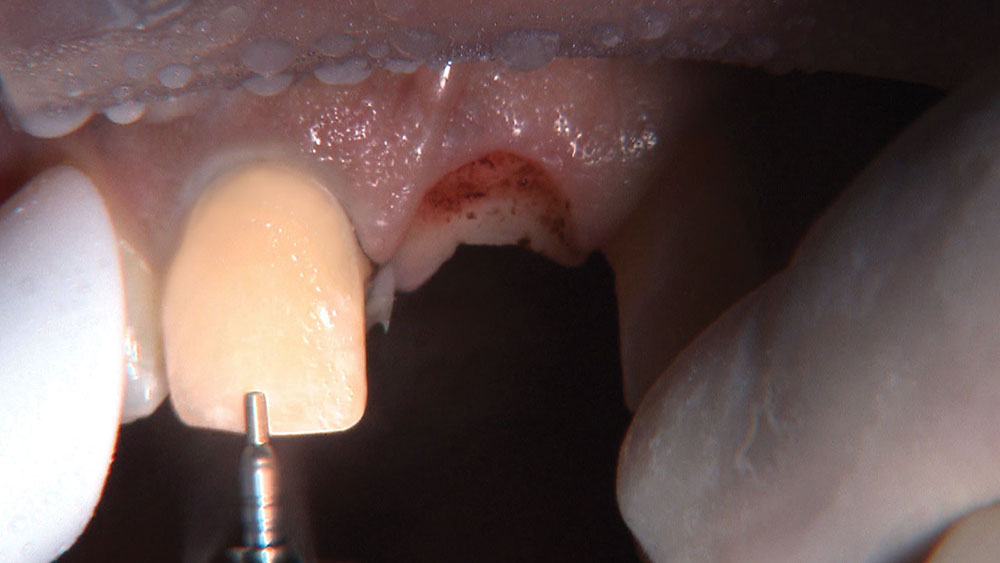

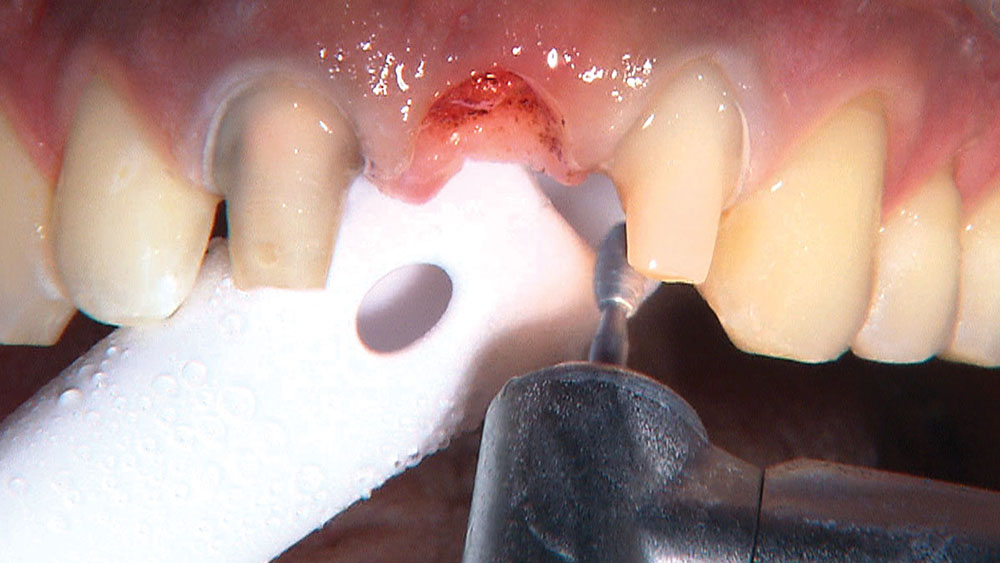

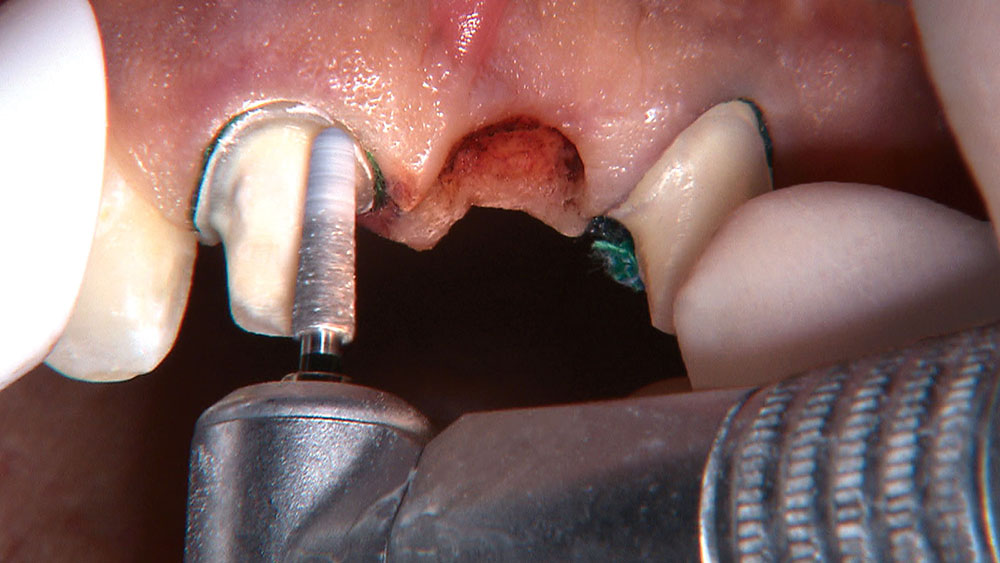

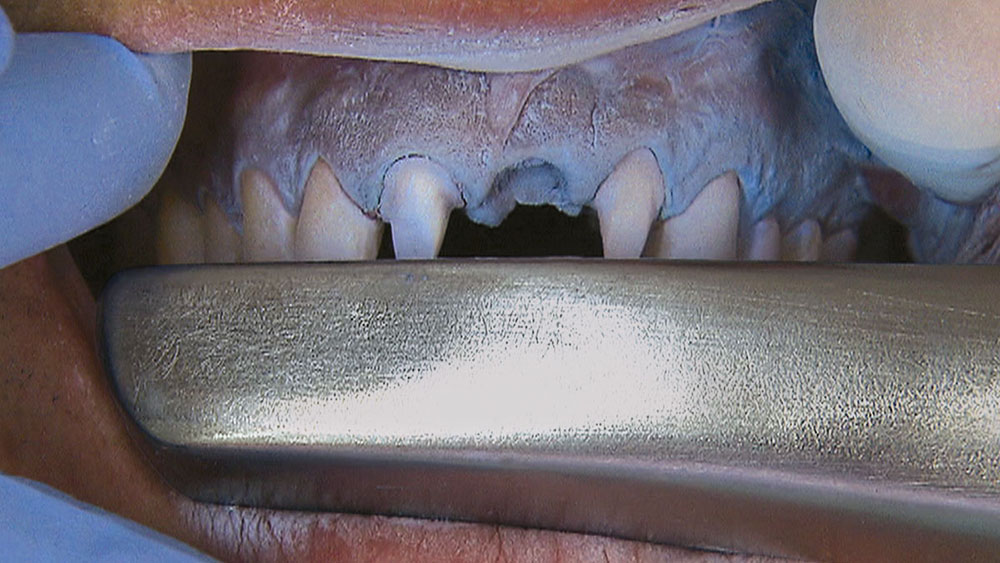

Properly angling the facial-incisal line back toward the lingual helps ensure the patient can get their lips around the final crown or bridge restoration.

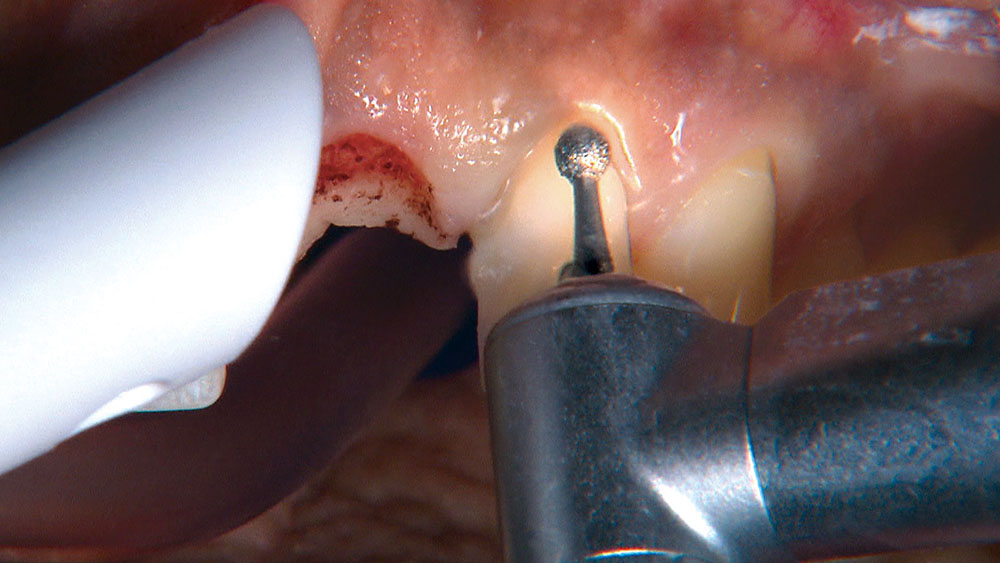

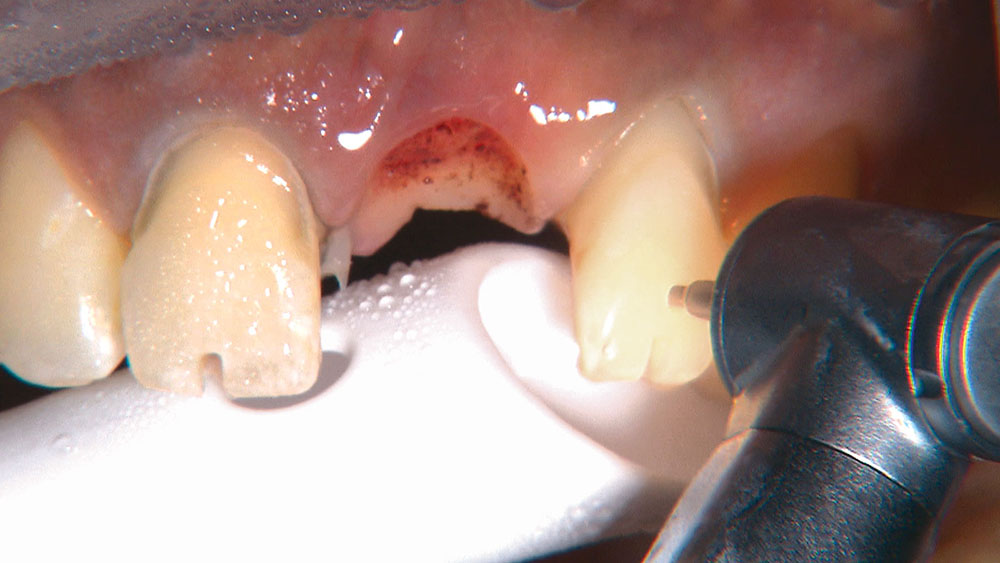

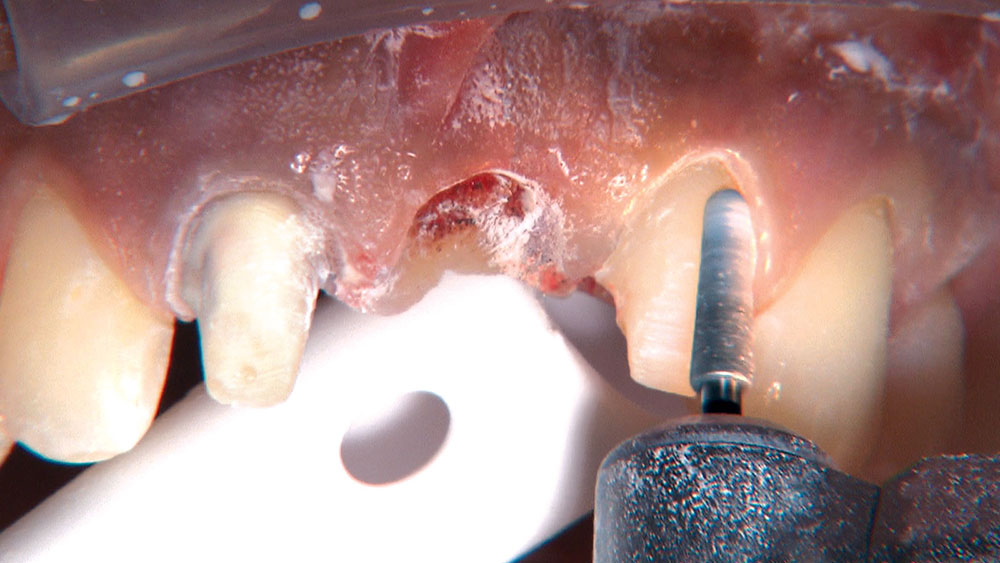

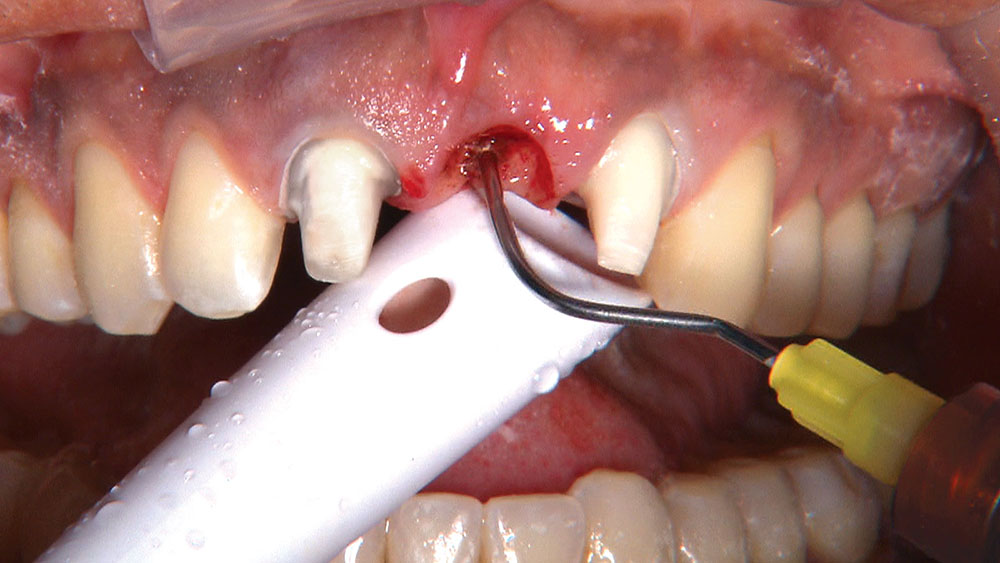

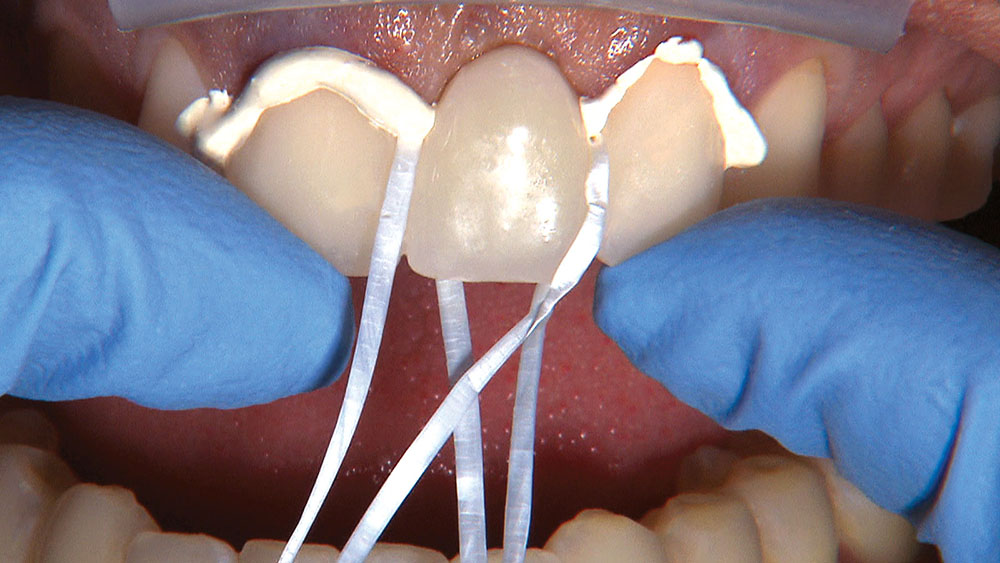

When creating ovate pontic receptor sites, you may find that you go all the way through the tissue and into bone.

References

- de Vasconcellos DK, Volpato CÂ, Zani IM, Bottino MA. Impression technique for ovate pontics. J Prosthet Dent. 2011 Jan;105(1):59-61.

- Gahan MJ, Nixon PJ, Robinson S, Chan MF. The ovate pontic for fixed bridgework. Dent Update. 2012 Jul-Aug;39(6):407-8, 410-2, 415.

- Alex G. A visual essay. Use of an ovate pontic to achieve optimal aesthetics and integration in the anterior region. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2008 Nov-Dec;20(10):589-91.

- Orsini G, Murmura G, Artese L, Piattelli A, Piccirilli M, Caputi S. Tissue healing under provisional restorations with ovate pontics: a pilot human histological study. J Prosthet Dent. 2006 Oct;96(4):252-7.