One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: Interview with Dr. David Little

Dr. David Little maintains a state-of-the-art dental practice in San Antonio, Texas, that houses a variety of specialists from distinct disciplines who are all able to contribute to each case from their own area of expertise. An accomplished international speaker, professor and author, he also serves as a clinical researcher with a focus on implants, laser surgery and dental materials. Discover what this forward-thinking clinician has to say about competing with corporate dentistry, the general practitioner’s role in implantology, and the future of the dental industry.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: I’m here with my good friend Dr. David Little from outside of San Antonio, Texas. David, I can’t remember exactly what city you’re in, but I remember it has an interesting name. What city are you in?

Dr. David Little: I’m actually in China Grove, Texas, a sleepy little town the Doobie Brothers made famous around San Antonio.

MD: I knew it had an interesting name, but I couldn’t quite remember exactly what it was. When I heard that song, I used to think that it was about heroin. You know, I just thought it was like a type of heroin because they were musicians, or maybe it was the name of a girl. But it’s actually about your town?

DL: It is actually a town just outside of San Antonio. Back then, they could get outside the city limits, so things like horse racing, gambling and some other things drew a lot of people out here.

MD: That’s funny. I remember they mentioned samurai in the song, which are of course Japanese, not Chinese. But I guess Japan Grove doesn’t roll off the tongue the same way China Grove does. How big a town is China Grove?

DL: Well, actually, China Grove is now a part of San Antonio, so San Antonio has grown beyond it. But technically, it’s always stayed a city within itself, and there are probably only about 1,200 people who still live here.

MD: And how many dentists are there in that community?

DL: Well, the good news is there’s only one.

MD: And it’s you!

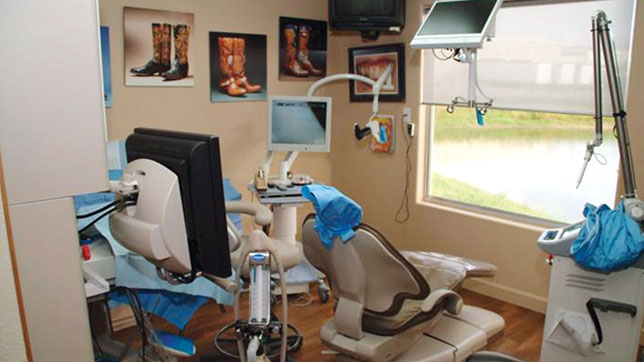

DL: And it’s me! But there are several dentists in the communities around it. Because I was located a little bit away from things, I set up an office where I started bringing all the specialists into my practice. Mainly, I did it just to serve the population, because they didn’t want to drive somewhere. I was, and still am, working at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Dental School, so I got all the residents that were working there and had them come provide their services on Fridays and Saturdays. Soon enough, that turned into us having a building where half of the office is complete specialty care. So we have kind of everything under one roof.

MD: So you have everything? Including a pedodontist?

DL: Actually, the only one we don’t have is a pedodontist. But my associate is our pedodontist. She’s really good with kids, so we haven’t found the need for that. But we have all the other specialties.

MD: Are they still there just a couple days a week, or are they actually there every day that you guys are open?

DL: We have a different specialist there every day. So it works out well because we can do joint consultations. If we have to, we can bring them all together at one time. It really just works well for patient care.

MD: Now I’m going to guess that because you’ve taken the time to put together that group, the convenience factor must be really high. So when you see a patient with super subgingival margins on a lower molar and it needs a new crown, you’re probably much more willing to send that patient to have crown-lengthening surgery because it’s right there in the same building, so it’s still income for yourself, but you have the skill of a specialist doing the procedure.

DL: That’s correct. It really works out well. The other thing that’s happened from this is our specialists have been great at educating us, teaching us and mentoring us so we can actually do some of those procedures now as well. Having that mentor right in the same office is great. You’re right: Patients like dealing with one staff and not having to go to another office.

MD: Do you feel this is something that every dentist could do? Or do you think that because you knew the residents and were in a smaller city, that this was something you were forced to do? It sounds like a great setup, and I wonder if more dentists would be able to do this and have all these specialists in-house.

DL: Well, I’d like to say I was really smart and did this as a good business model, but the truth is I did it really to serve my patients. In my situation there just wasn’t a better option. They would have to drive 20 miles to go to a specialist. So I’m not sure this type of practice would work if you had all the specialists already within an accessible distance to you. But convenience is a big thing, and I think patients really like this model. We’re even seeing this in some of the big group practices now. So it’s been a real benefit for us, and in the right situations, it’s a win-win for everybody. Now the big concern you’re going to run into is that other specialists think that now no one is going to refer to them if they’re not located all in one place. And what’s happened in our situation is that I’ve gone to the dentists around my area and said, "Look, I’m not going to steal your patients." And knowing that, those dentists aren’t going to refer their patients to someone further away. Doing so would be bad for them. So I see us as a service. Let them use it. Our specialists have referrals from all over now, so it’s been a great situation for them as well. For example, my oral surgeon is an MD as well, and it’s opened up a lot of medical referrals that we didn’t even think about. Plus, you know what? I just enjoy having the interaction, and it also allows us to do a lot bigger cases. We do a lot of full-mouth extractions and immediate implant placements. Having so many specialists around is why implants are a big part of what we do, because we can do everything right there and make it really nice.

MD: I would guess you’re able to do sedation cases because you have the oral surgeon there as well?

DL: And that’s a really big thing. Because we have a periodontist and an oral surgeon in my office, we can have whatever sedation the patient wants. One of my associates is certified in anesthesia as well, so we can offer everything from just pill form to IV sedation to non-narcotic sedation methods. It’s about what the patient wants. It seems to me, more and more, they’re actually requesting less sedation if they can.

MD: The way you describe it, it feels to me like the GP practice of the future. Or at least it’s the strategy for the GP practice that’s going to be able to compete well with corporate dentistry, which is able to do a lot of these same things and be open Saturday and Sunday while really trying to focus on convenience for the patient. What you’re doing is the same thing.

When we met for the first time, which I believe was back in 2001, we were both involved with the very first generation of zirconia, which was Cercon® from DENTSPLY (York, Pa.). It was a zirconia substructure with ceramic fused to the outside of it. Do you remember those days? And do you remember doing those restorations?

DL: Absolutely. Absolutely. Look where we are today! You guys are obviously the leaders in what’s happening in that industry, and it’s so great to see zirconia come to fruition.

MD: In the Cercon days, it never occurred to any of us that the right thing to do might be to take all the porcelain off of the coping and make the whole crown out of the coping material. The copings were snow white, and we had to cover it up with enough porcelain so that it wasn’t showing through. The material was like a B3 shade, so it really never occurred to anybody that it might be a good idea to make the restoration entirely out of that. It was Ivoclar Vivadent (Amherst, N.Y.) taking the ceramic off of IPS Eris® and turning it into IPS e.max® (Ivoclar Vivadent) that kind of got people thinking, "Maybe we don’t need ceramics on these restorations to still have them look good." So monolithic restorations are now the majority of what we do at the lab. How did you get involved with monolithics, and where do you use them?

DL: Well, like you said, we started way back. I remember it was a challenge for the technicians to try and block out the whiteness of it. My big concern was that the core would be so hard that it’d never work. But when we started looking at the wear studies, they showed how kind polished zirconia is. The big thing for me is that the prep for zirconia is so much less than what we had to do before, so I think that’s why the change has happened. And here’s the other thing, too: All of us dentists would put in a gold crown as our first choice if we could; that’s probably what we have in our own mouths. If we tell patients that we can do something just as strong as gold, but it’s actually going to look natural, you know which one they’ll want. With zirconia, I have confidence that prescribing it will be a durable solution. I’m doing the BruxZir® crown on top of most of my implant abutments today because, again, you’ve got all the benefits while not having to worry about it fracturing.

MD: I just finally placed my first implant a couple years ago. I was terrified to do it, because I’d seen an X-ray where the implant was put right into the root of a tooth. Putting an implant into a root, sinus or their mandibular canal: That’s the kind of thing that had me terrified of getting into implants. I wasn’t willing to place my first one until surgical guides came out. When I finally started placing them with surgical guides, it felt easier than doing a 3-unit bridge. I thought, "This is easier than molar endo." You said you do mostly implants now: How did you get the courage to do that first one? Because we still aren’t seeing that many GPs doing it on their own.

DL: One of the things that I had benefitting me was an oral surgeon and periodontist looking over my shoulder when I started. And what’s great today is that CBCT-scanning technology lets me decide right then and there whether I do or don’t want to do a case. I think general dentists should be placing implants or, if nothing else, should be educated on everything that implants can do for patients. As a general practitioner, getting the information, taking CBCT scans, using surgical guides, and seeing the end before you start: That’s the key. Like you said, once you do all the homework and plan it, the execution is not that difficult. General dentists do a lot of things more difficult than that: endo and third-molar extractions, for example. Let’s face it, 80% of implants are single teeth. That’s where general dentists live and breathe. We should be doing implants versus a 3-unit bridge. I’m not saying bridges are bad: If you have two broken-down teeth, I think that’s a great solution. But if you have two virgin teeth, implants are the only care that should be given. With the proper education, we can place implants and do a great service for patients.

MD: If a patient‘s got, let’s say, an old PFM bridge from #18–20 with the porcelain fractured off and some recurrent decay at the margin, what kind of conversation will you have with that patient about replacing the bridge versus two separate crowns with an implant?

DL: The biggest thing is the preservation of bone. You can actually show the patient that the bone has gone away since that first bridge was done, and then explain how that can lead to perio problems and other recurrent decay issues. Being honest, I say: "You’ve gotten 17 years out of this bridge, and we could do another one to get 17 more years. However, usually if I’m going to replace something, I want to replace it better than I could the first time." In an ideal world, I would put the implant there to maintain the bone, which would affect the health of those other teeth.

The other thing I ask — and this is a simple thing — is, how did you like flossing the bridge? And most of them say they hated it. And I say: "Well, that’s another big advantage. We can make individual teeth where you don’t have to do that." I also explain that the strength of those teeth by themselves is better than when you tie them together. So long-term, you’re going to be better off with implants in that situation.

MD: I’ve found when I ask patients how they like flossing their bridge and they say they hate it, that’s just a lie: They’ve never flossed the bridge. When we delivered the bridge three years ago, we gave him three floss threaders to use; and now three years later, when we ask if he needs any more, he says, "No, I’m good." You really made three of those last three years? What did you do, put them in the dishwasher? What exactly are you doing to keep these threaders in such pristine condition? We’ll take off the bridge and see that it’s just completely irritated from lack of flossing. So you’re right about the bone and you’re right about the perio condition, too. If they want to keep those other two teeth, they’re better off having three separate teeth.

DL: Yeah, I totally agree.

MD: And what about the fee difference, David?

DL: When I first started doing this, it was four times more to do the implant than a bridge. That was a big difference. Today, I’m going to tell you that it’s still a slightly higher investment; but in the long-term, it’s a much better investment. And that’s how I present it. The reality is that the bridge is going to last seven to 10 years on average. If you really take care of it, it’ll last longer. But if you’re 40 years old, you have to think about how many times over your lifetime you’re going to have to replace that. And also know that when we place it, because of decay, we might have to do root canals. So your most predictable investment is to do an implant. Most of the time, that’s what people go with.

MD: I actually like to congratulate people sometimes when I see someone who’s missing a lower first molar that’s been gone for 15 years. I know he just procrastinated because he’s a male, but I’ll say: "Congratulations, you made a really wise decision. Even though I wanted to do that bridge you kept saying, ‘No,’ because you knew there was something better. And it’s here today, Mark. We can put an implant there to replace it, and we don’t have to grind down those other two teeth." I don’t actually do it quite that glibly, but I like to frame it that way. They always wondered why we’d have to do two other teeth. "Why is it three teeth? Why can’t you just glue a tooth onto my gums?" And I was like, "Well, we don’t have that kind of crazy glue." But now, essentially, we do with an implant and a crown.

David, I’m wondering what your thoughts would be on the concept of a modern extraction. Let’s say starting in the year 2020, we have a new concept of a modern extraction: Every time we remove a human root, we’re going to replace it with a titanium one, regardless of whether or not the patient wants a crown and an abutment on top of it. How radical of an idea is that? Does it make sense to you?

DL: I think it makes sense, actually, and I don’t think it’s as radical as you think. The year 2020 is not that far away, and maybe we’ll see it before that. The technology keeps getting better, and any time we can preserve what’s there, that’s the best thing. You and I both know sometimes patients don’t want to do anything for a long time. They come back later and say, "Now I’m ready for that implant." But now they don’t have enough bone to do it. This is why I promote at least grafting the socket so that you prevent that 25% loss in the first year, which gives them a chance to do that implant later. I remember 30 years ago, we used to wait a year before we’d put anything in. Now we realize that an immediate replacement is a reality. What you were talking about is not farfetched, and it’s actually being done. I have a saying, "If it’s being done, it’s probably possible." And I think that immediately placing a titanium root is something we’re going to see more and more of.

MD: It makes a lot of sense to tell a patient: "We tried to save that root, but now it has to come out. But don’t worry: We’re going to put another one in when we take the decayed one out." I think that’s how patients want it to be: somewhat like a typodont, where you unscrew one and then put another one back in it. It feels like we’re getting closer and closer to that. And with the CAD/CAM technology that I see around our laboratory, I don’t think it’ll be very long before we scan the tooth and the root while still in place, and then mill an implant out of zirconia and place it right into the fresh extraction site.

DL: I could see that happening. I like the word “artificial root” versus an implant. And you know patients like that terminology better, too.

MD: Instead of paying $120 to take out a tooth for an extraction, why can’t it be $550 — or whatever it is to place an implant as they become more affordable — to have the extraction include putting in a new root? That way, three years from now when both of their kids are out of college, we can go ahead and restore that tooth.

DL: That gives us all the benefits without losing anything.

MD: Exactly. Now speaking of CAD/CAM, how involved are you with that technology in your office right now?

DL: We have iTero® (Align Technology; San Jose, Calif.), so we’re doing scanning, but we’re not doing any milling. We really enjoy that technology, and our patients enjoy that technology. Patients think it’s a lot better than putting the goop in their mouth. Plus, there’s the increased accuracy, and just the wow factor. The technology is going to continue to grow, especially with what Glidewell is doing: I can send you a digital file and get a crown back. That’s awesome. That’s amazing technology.

MD: We give a discount to people who send us the digital file because it saves us so much work. Typically when a case comes into the lab, we take the vinyl polysiloxane impression, pour it up in stone, saw the dies, articulate it, and then finally scan it. It took man-hours and materials to get us to the digital environment. But when you send us a digital file you’ve saved us all that work and material, which we’ve calculated to be about $20, so we pass those savings on to you. At the lab, we feel like if you’re going to invest in that technology, sure, it’s going to make your life easier and impress the patient, but it’s going to make our life as a lab a lot easier, too, and we feel like the dentist should be rewarded. The number of digital impressions that we’re getting is up 200% over last year. It’s still slowly catching up to vinyl polysiloxane impressions, and that’s probably the way it should be. I’m almost glad that nobody’s come up with an intraoral scanner that’s so easy to use, everybody could own one. Because right now, with this generation of cameras dentists are forced to take a little better care of the tissue than they would with vinyl polysiloxane or with a better technology. Do you agree with that?

DL: Totally. And it’s better for you guys as well. It’s not like we can just take impressions with VPS, look at it and say: "This looks pretty good. The lab will be able to make this work." With digital scanner technology, you are forced to look at it on a 17-inch monitor and actually see the errors you made on the prep. It’s made me a better dentist. My preps are better because of it. And until they get the holy grail of scanners, you’re still going to have to manage the tissue.

MD: Yes, I completely agree. The holy grail will be when a scanner can see through blood, tissue and saliva, and be able to be used for subgingival margins and other things where there’s limitations right now. So I do feel like the right amount of dentists are using it right now because it is a little more difficult and it forces you to treat the tissue better. Sometimes dentists will say they like the idea of doing it, and they’d like to save $20 per crown as well as be able to tell their patients that they’re the high-tech practice in town; but by the same token, they’ll say that they just don’t know if they’re going to be able to handle this and make it work well. It’s so slow compared to a vinyl polysiloxane impression. Maybe it’s not super efficient for taking impressions, maybe it’s not as quick as the 27 seconds with polyvinyl, but it is the only real technology that I’ve seen in dentistry that will make you a better dentist. There are just no two ways about it. If you say you want to get better as a dentist, I don’t know any better way for you to improve than to start using this.

DL: And you have to factor in how well the restorations fit and how much less chair time you’ll have to spend seating the crown. If you do it well, every restoration falls into place the first time. I think there’s no happier way to seat a crown. And the patient enjoys it. That is the greatest thing.

MD: Speaking of that, I’m all about trying to not only reduce remakes, but reduce chairside adjustment time. I know as a dentist that drives me and other dentists crazy. Here’s another benefit of digital technology: When somebody like you sends us a digital file, literally three minutes after you send it, it’s on a computer screen and we’ve got somebody logging it in as your case; they send it out to a designer and there’s a crown design for it within about 12 minutes; and then that gets sent down to the milling center where we can mill an e.max crown and overnight it so you get it the next day. It’s a little harder with BruxZir because of the sintering time, but you can have it back on the third day. The amount of chairside adjustments and remakes has gone way down when we went from seating crowns at two weeks to seating crowns in two or three days. I can tell you from my experience that three-day dentistry is a lot better than two-week dentistry, which just seems to be an artifact of the way dentists have always done it. Do you think it would be difficult to incorporate three-day crowns? Are you ready to see the patient again after three days?

DL: Mike, I think that would be an awesome way to do it. You and I know that the quicker we can place that crown, the better it is. Fewer things are going to change. It’s going to be a good solution, and not having the patient in the provisional restoration for a long time is a big plus. We all hate it when provisionals come off. There’s nothing worse than having to re-cement a provisional during that two-to-three-week period. Being able to take that out of the equation is a big plus. The only thing doctors have to do is take the paradigm shift. It really is not that difficult, especially if it seats so easily. It’s a win-win all the way around. So I really see the benefit in that, and frankly, I would rather do that than try to mill it in my office. I just prefer not to be designing. I’d rather leave that to the guys like you who can do that.

MD: Well, let me ask you this: What if you bought a CEREC® (Sirona Dental Systems; Charlotte, N.C.) milling unit that came with a lab technician duct-taped to the side of it? Would that change your mind about it? If all that you did was prep the tooth and then take a digital impression? Because that’s how I do it here. I’m in a building with 832 technicians, so all I do is prep it. As soon as I’m done with the scan, the technician takes it on a thumb drive, designs it, mills it, stains it, glazes it, and brings it back to me. This is the greatest thing in the world. I’m doing chairside one-hour dentistry, and I don’t have to do anything different. I wonder how you would feel if it came with a lab tech that could do it. What do you think about that?

DL: That’s a game-changer absolutely. That’s the part I don’t want to be: I don’t want to be the lab technician. But having it work together? That’s the best.

MD: Well, you’ve hired so many other specialists to work in your office, this would just be one more specialist. This laboratory technician would maybe just be in on Thursdays and Fridays, but it would allow you to do anterior crowns and upper same-day smiles. That’s an idea that I have, but I don’t know if it will ever be a viable business. But when you look at the numbers from the National Association of Dental Laboratories, the number of labs continues to shrink as more work unfortunately goes offshore. There are a lot of technicians who are out of a job, and I think it would be great if there were three or four in San Antonio who could service all the dentists in the area so you didn’t have to be the lab tech.

DL: That would be a great model. There are a lot of technicians that never get to see the restoration in place. When they do, it really opens their eyes and lets them see what an impact they have on patients’ lives.

MD: Any chance I get, I’ll bring technicians into my operatory, let them watch everything that we’re doing. There are two simple things you can do to get better esthetic quality from whatever lab you’re working with: When you’re doing an anterior tooth, send them a picture of a shade guide next to the tooth you’re trying to match; and start sending the laboratory technician pictures of the finished crown in the mouth so they can see what it looks like. When you give the lab technicians a roadmap, when you send them a picture of a shade tab, they will try harder without charging a penny more because they know you care enough to help them out.

DL: That’s the best communication tool possible: a straight-on picture with a shade tab. I’m sure every technician loves that. On finished anterior cases, we’ll actually send a final picture of either my assistant or I with the patient just smiling. Not the intraoral shot, but the patient smiling, with a note saying, "Thank you for my beautiful crown." Those technicians will look for my cases the next time because they get to appreciate what’s really happening on the other side. Technicians tend to not realize how much they affect patients’ lives. It’s an amazing thing, and it’s their skill that’s making that happen.

MD: I totally agree. That is one of the things that’s special about being in a building with all the technicians like I am. If we’re doing a case of anterior e.max crowns, the technician can come up and see the patient try the crowns in the mouth. They’re the artists in the restorative process. Dentists are more like the demolition guys who go to Vegas and blow up the old casino. We just go in and blow up all the enamel off the tooth, and then they come in and build the new hotel resort that’s going to wow everybody. If you had that technician in your office, David, you could do teeth #7–10, and you could actually have the tech do a custom shading right there in the office. So I’m not trying to sell you a technician — we don’t have one for sale — I just like this idea and I know you’re open-minded, so I wanted to throw it out there.

DL: I love the team approach. I’ve seen it more with the all-on-six, all-on-four cases that we’re doing because we have the technicians come in and do the provisionals and then go to the final. That interaction with the patient is critical, just critical.

MD: If you’re doing this many implants, you probably own a cone-beam scanner. Which one do you have? How did you make the decision to get it, and what benefits are you seeing from it?

DL: I actually have the CS 9000 3D Extraoral Imaging System (Carestream Dental; Atlanta, Ga.). I got it because I have an endodontist, oral surgeon, periodontist and orthodontist in my office, so I needed the cephalometric, panoramic and 3D capabilities, and it fit all of those roles. The other reason I bought this one is so I can do just the sections. Like if I was just doing a single tooth, I didn’t have to do the whole arch. That’s worked out well. But the machine is not just about implants. Sometimes a patient will come in and have a pain that you can’t tell which tooth it’s from. You’ve looked at every technique you know, and you still can’t see anything. When you take a quadrant CT, you can usually see a fracture or another root or something that you couldn’t easily see otherwise. So it’s just an invaluable tool for diagnosis. The real key is what you do with it, and that’s where Glidewell does so well, because we can send you a scan, and you can help us put it into a software so we can manipulate it and plan the case, and then fabricate a surgical guide. That team approach is just huge in the implant world.

MD: I don’t want to date ourselves, but we both have been out lecturing for eons, it feels like at times. What would you say is probably the most common question that you get from dentists?

DL: On the implant side, their big concerns are costs. That’s one of the things that comes up every time. They’ll say, "Wow, a surgical guide costs ‘x’ amount?" And I’ll say: "It’s about chair time. To be able to go in and predictably do what I need to do in a short amount of time with fewer complications is well worth the cost of that extra part."

And the other question is: "Where is all this going?" I’ll get asked which scanner is worth it, and what happens if this technology changes. I lecture to the dental students every year, and I love to tell them that it’s a great time to be in dentistry because they’re going to see the real benefits of technology. I think we’re in an exciting profession.

MD: We had one of the deans from Midwestern University College of Dental Medicine in Phoenix, Arizona, here in the lab touring last week, and the most amazing thing that I heard from him was that in their four years of school, students are required to do six CAD/CAM crowns to graduate. They do four in pre-clinical and two on actual patients. I was blown away because at every other dental school where I’ve lectured, it’s just an elective, and maybe 10% of the class does one of them. This dental school is graduating all these doctors familiar with CAD/CAM crowns. To them, going back to a PFM must seem like blacksmithing technology. So I agree. I can’t imagine a more exciting time. I always remember my dad saying the same thing in 1960. When he was in dental school, he talked about how exciting dentistry was when the high-speed handpiece came out. And I guess if you’re using a belt-driven one, the improvement would make his statement absolutely true. But with the ability to do all the things we can do today — see in three dimensions, place implants at the time of extraction, mill chairside restorations — dentistry is extremely exciting. Twenty years from now, when you and I are gray and our hands are shaking, I’m sure this new generation is going to be telling us how we had nothing to compare to what they’re doing.

David, thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate you being generous enough to share some time with our readers. I really think the type of practice you’ve set up there is the model of the future. GPs who follow your lead will be really well set up to compete with corporate dentistry.

DL: Thank you, Mike.