In orthopedics, a splint is often prescribed to support a load-bearing joint (e.g., the knee) that has been strained or damaged. This splint is coupled with the articulating bones that comprise the joint and then assumes a portion of the purposeful ambulatory functional load. Joints that are not subject to the forces of gravity, such as the elbow, are not splinted, but are simply isolated to minimize their use.

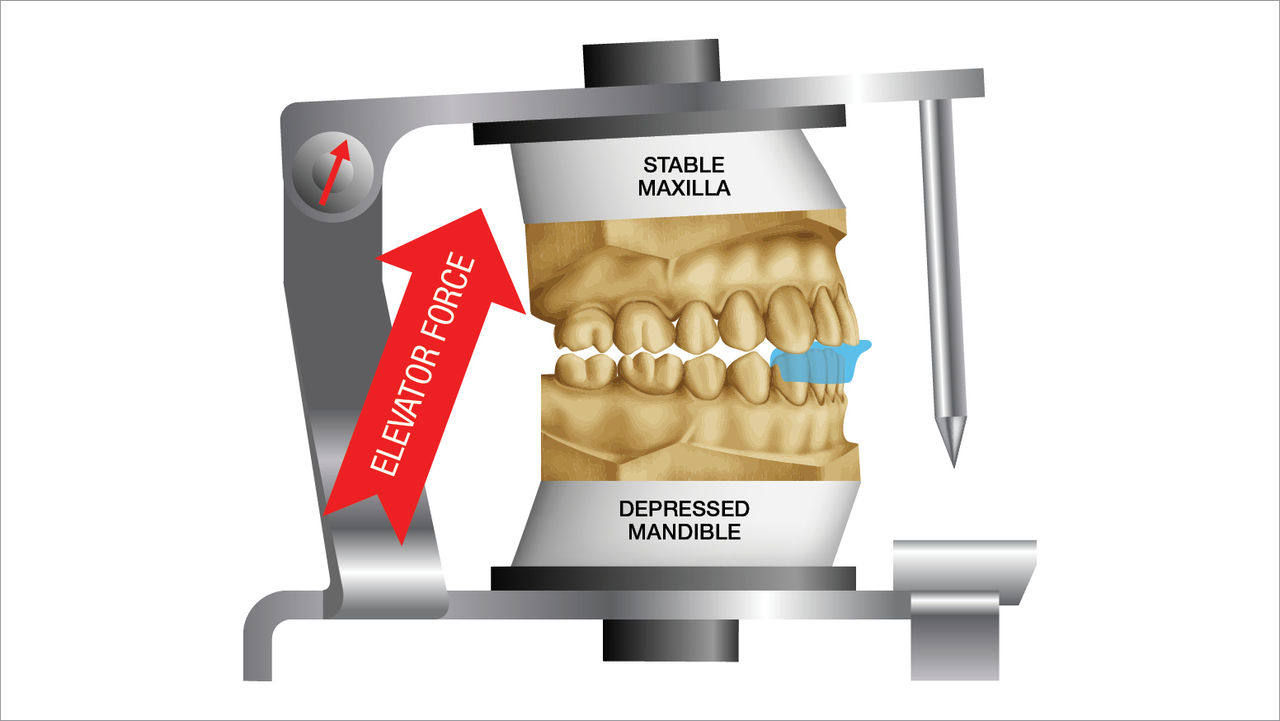

An occlusal splint is often prescribed to minimize the strain or load on the TMJ, but the TMJ is not subject to the forces of gravity. The splint is not coupled to either the maxilla or mandible, and it is not used during purposeful functional mastication. There are many types of occlusal splints to choose from, but most are commonly used during sleep and often have no effect or influence until parafunctional activity ensues.

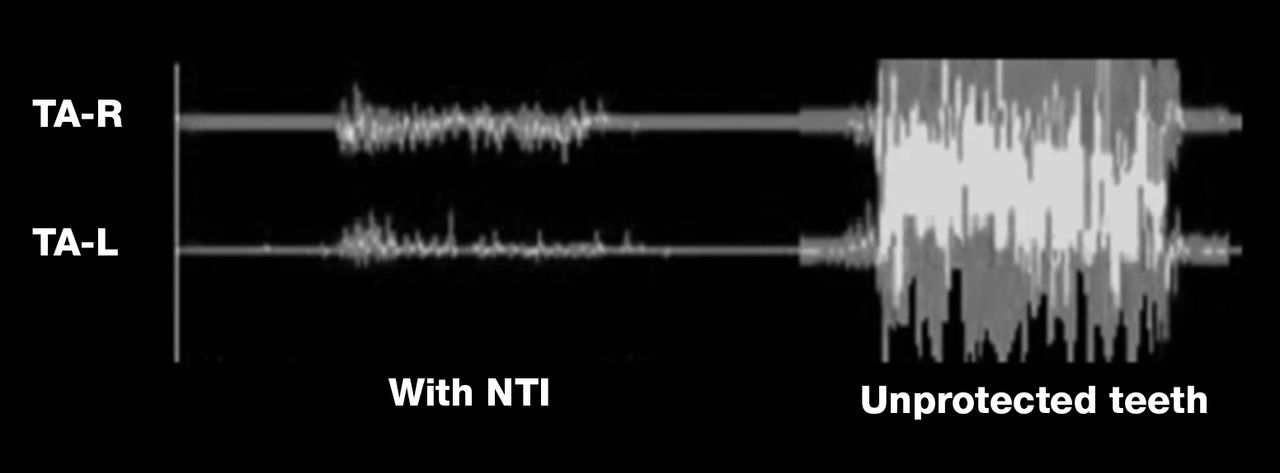

Not until the muscles of elevation are innervated does an occlusal splint have any effect. The splint assumes the role of the occluding surface of one of the arches. Upon contact with the splint, the occluding scheme provided by the splint then influences the parafunctional activity.

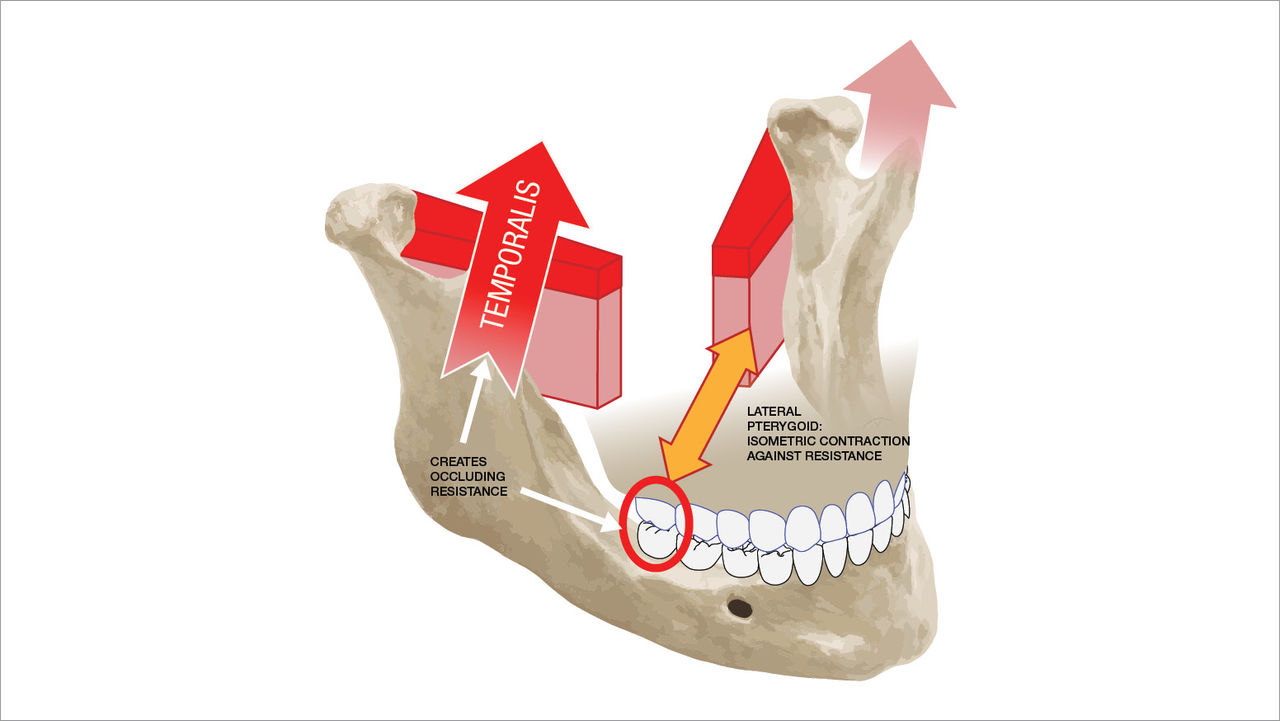

Stemming from the initial training with an articulator, the practitioner stipulates occlusion and therefore can wrongly assume that posterior interferences cause muscle hyperactivity, when in reality, the existence of a posterior contact is the result of elevator hyperactivity. Because the practitioner knows that occlusion or clenching is going to happen, the first order of business is to ensure balanced occlusion by spreading the forces resulting from the persisting elevation, such as that caused by clenching, throughout the splint to avoid traumatization of any individual teeth. During a clenching event, where the mandible is centered and the occluding contacts are spread evenly throughout the splint, there is no adverse strain or load on the TMJ.