Case Presentation: Simple Bailout for Complex Periodontal Dilemmas

Restorative dentistry, in particular full crown restorations, often causes complex periodontal problems for patients. Many restorative dentists select full crowns to restore teeth that have lost significant tooth structure caused by decay or fracture, or resulting from previously placed restorations that were large. Frequently, full coverage restorations are the only way to manage cases like these; unfortunately, they can trigger issues that ultimately compromise the patient’s health. With the ever-increasing body of scientific evidence correlating periodontal infection to systemic disease, any treatment protocol that promulgates infection should be avoided, if possible.

I prefer to use partial coverage restorations to restore teeth because they enable the preservation of biology, which is foremost in my mind as a preventive restorative dentist. Unfortunately, many teeth just need full crowns and there is no other option. Problems are created, however, with full crowns when the margins of the crown extend into the sulcus, which is somewhat of a paradox, because full coverage is often mandated by pathology that extends subgingivally. However, hundreds of published scientific reports overwhelmingly conclude that subgingival margin placement creates periodontal infection. One does not need a lot of science to document these issues, as they are readily evident upon mere clinical observation of almost every crown with subgingival margins. Gingival bleeding occurs easily upon probing or vigorous toothbrushing around such restorations, thus providing a portal of entry into the patient’s vascular system for the inflammatory byproducts of infection that may prove fatal. A small percentage of patients are immune to iatrogenic periodontal infection; however, it is difficult to determine in advance if the patient is susceptible to this undesirable side effect of our treatment or not. Therefore, it is prudent to avoid subgingival margins in crown and bridge dentistry whenever possible.

Replacing old dentistry that has severely compromised periodontal and pulp health presents one of the greatest challenges in restorative dentistry. Certainly, the option of removing the teeth and placing implants is often the easy way out from a treatment perspective on many of these cases. However, many patients simply do not want to lose their teeth. The case presented here represents one such case that my periodontist, Dr. Dan Melker, and I treated a number of years ago.

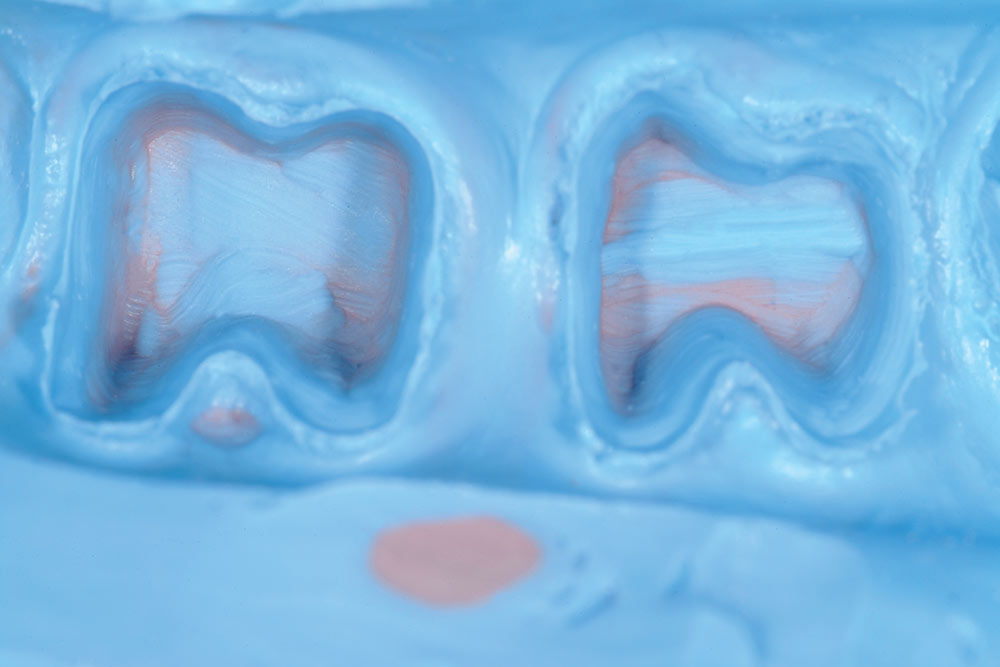

Rita (Name changed to preserve the patient’s privacy) presented to my office with three full porcelain to metal crowns on the mandibular right quadrant, #29, #30 and #31. Significant bleeding occurred upon probing or vigorous toothbrushing. The teeth had been treated historically with full crowns and shortly thereafter the molars had been treated endodontically. The soft tissue around the crowns was swollen, red, sensitive when probed, and glistened without stippling. The crown margins were open, rough and subgingivally placed. Porcelain was worn and fractured on the molars. Caries was obvious to the touch with an explorer. The occlusal size of the teeth buccolingually was enlarged. Lateral occlusal interferences existed in both working and balancing excursions. Horizontal bone loss in the furcations was significant, especially on #30. The patient reported discomfort when chewing on these teeth. The cosmetics of the case was fair to poor. The patient was unable to clean plaque from the restorations.

My diagnosis of the case was carious and periodontal infection as well as occlusal trauma. The prognosis of the case was good with proper perio-restorative treatment by me and Dr. Melker, combined with the education of the patient about preventive practices. I determined the etiology of the pathology to be iatrogenic crown and bridge dentistry, as well as possible cement sepsis.

I prefer to use partial coverage restorations to restore teeth because they enable the preservation of biology, which is foremost in my mind as a preventive restorative dentist.

When establishing a treatment plan (in this case, new crowns after appropriate periodontal surgery) it is imperative to establish the etiology of the pathology to assure that the outcome of proposed treatment would be different than the outcome of the previous treatment. Often, a bit of forensics is required to glimpse into the reason for clinical failures such as Rita’s case.

From the patient’s history, we learned her crowns were five years old and were placed to address large fillings and fractures of the teeth. It was easy to ascertain how the current failure occurred after the old restorations were removed. Gross microleakage caused significant decay, cement dissolution, pulp pathology and tissue infection. The suspected cause was cement sepsis, a clinical scenario that plays out under all too many restorations with subgingival margins. Frequently, such clinical management results in missed impressions, poor marginal adaptation of provisionals, and inflamed tissue at cementation.

Cement contamination occurs when restorations are cemented into a pool of blood. The result is cement sepsis; a process where the compromised cement allows microbial growth in the cement zone under the restoration, causing carious and periodontal pathology.

Caries result from acids produced under the crown by microbial growth. Likewise, periodontal infection results from the microbial growth under the crown that cannot be controlled by preventive measures. Pulp pathology often is immediate, as was the case with Rita. She advised us that she had experienced extreme sensitivity after the preparation of her previous crowns and suffered a bad taste around the temporaries. This lead me to believe that the pulp was insulted both during the provisional phase and later when the crowns were cemented into the pool of blood that accompanies provisionals that do not fit properly.

Dr. Melker and I use an exacting protocol for approaching these kinds of cases. It requires a team approach with everyone paying attention to the smallest of details. Our objectives are to create an environment that facilitates the control and prevention of microbial infection so the restorative dentistry is easier, more predictable and profitable. It makes no sense to avoid sending a patient to the periodontist when it makes the case easier, more predictable and more profitable.

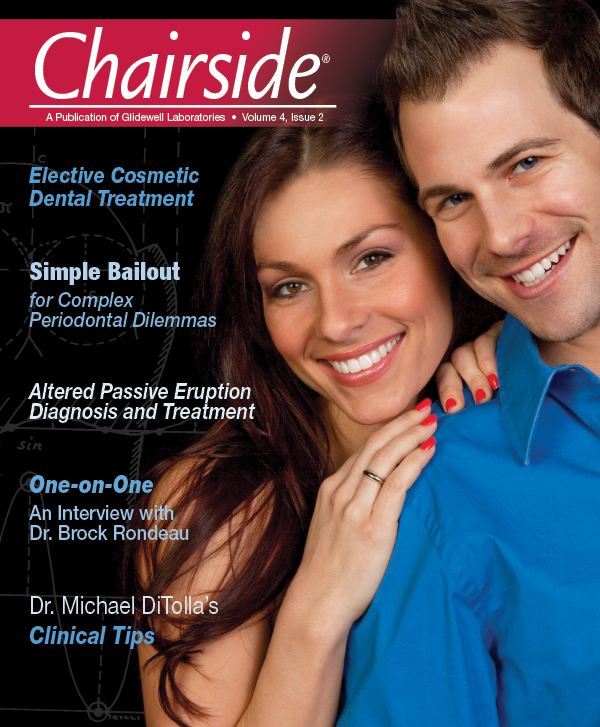

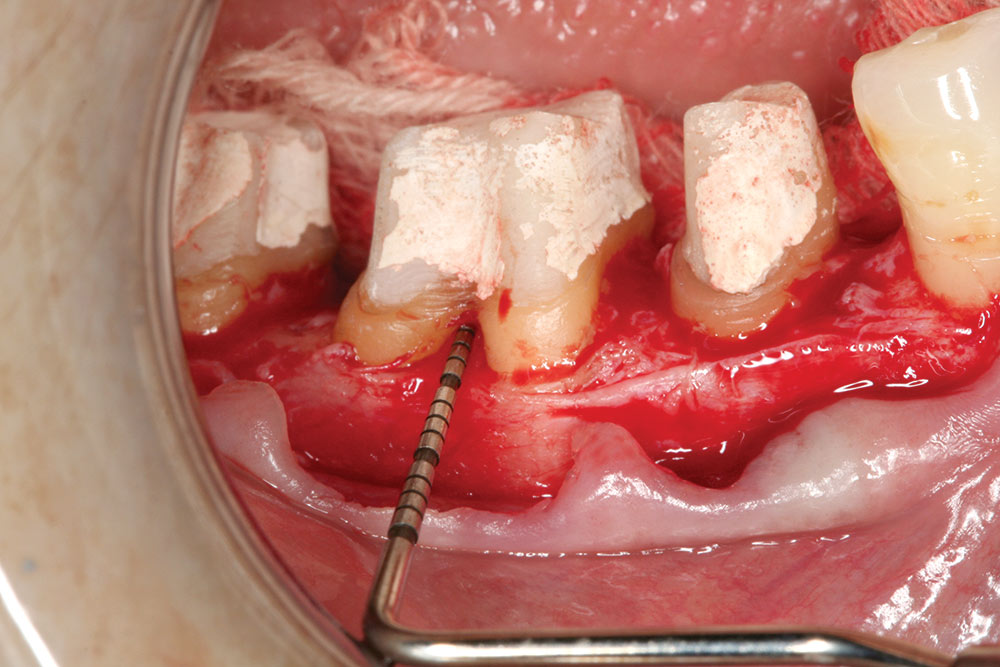

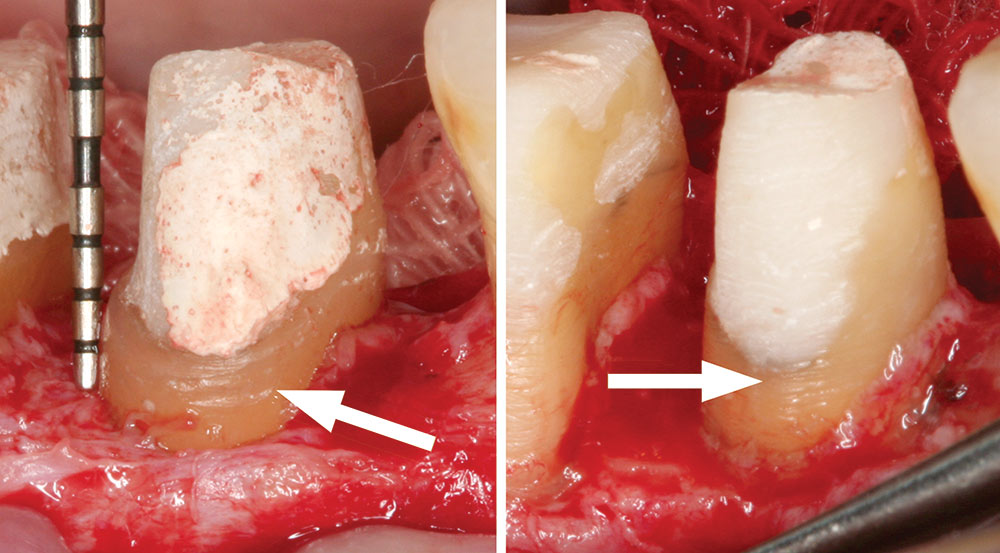

Provisionals are required, then removed at the time of surgery to allow vertical access to the prepared tooth. The old restorations and caries are removed and core buildups are done so the extent of compromised tooth structure in an apical direction can be assessed relative to the biologic width.

Rita’s crowns were removed along with the gross caries, stain and old filling material. Core buildups were done using a specific bonding protocol for self-cure resin composite. The provisionals were cemented with polycarboxylate cement, which is antimicrobial and sticks to the teeth when the provisionals are removed. The teeth were sealed with Super Seal® (Phoenix Dental, Inc.; Fenton, Mich.) before cementation to protect the pulp in #29. Because the cement sticks to the tooth, when microleakage occurs under the provisionals, microbial growth is restricted between the cement and the intaglio of the provisional, thus denying microbes access to dentinal tubules.

Surgical provisionals are easily removed, using mosquito hemostats in a gently rocking motion several times from the incisal/occlusal. Aggressive forces should be avoided to prevent tooth fracture. Surgical provisionals must be made of methylmethacrylate, not bis-acryl, because the provisional must be able to flex for its removal. Bis-acryl does not flex; it fractures and is, therefore, unacceptable as a surgical provisional material.

Surgical provisionals and core buildups are done two weeks before periodontal surgery. This two-week period gives the soft tissue an opportunity to heal and to recover from the microbial insult of the microleaking crown and operative damage associated with caries removal and core buildups. It also allows vital pulps to settle down. Many times what seems to be an irreversible pulpitis goes away when the etiology is removed. Sensitivity to hot, cold and biting pressure often occurs in teeth exposed to microbial assault from microleaking crowns. In many cases, two weeks of protection from microbes is often all that is required for pulps to become healthy again.

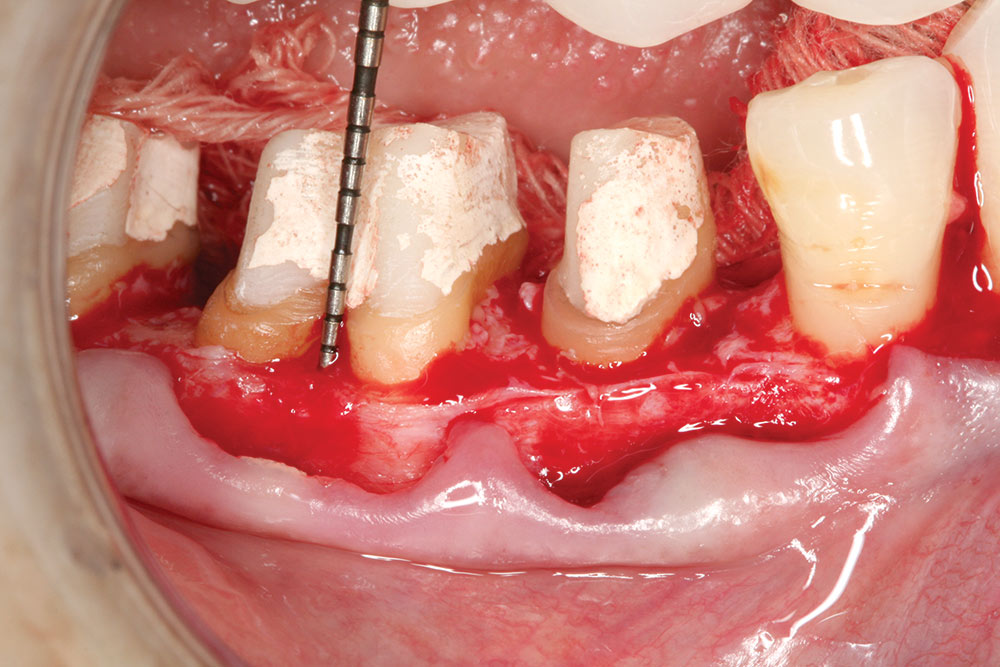

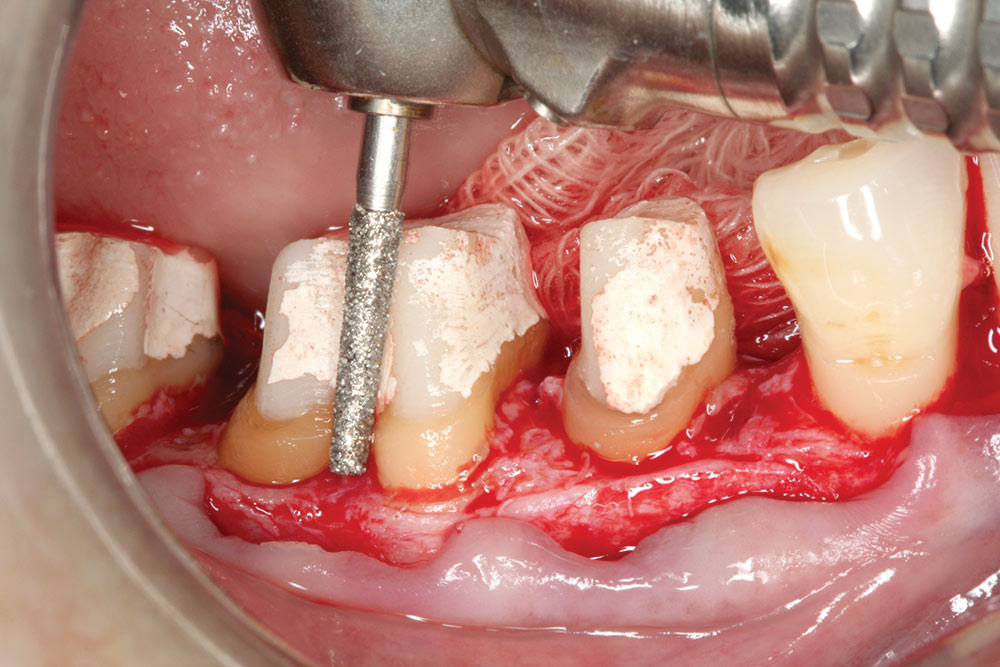

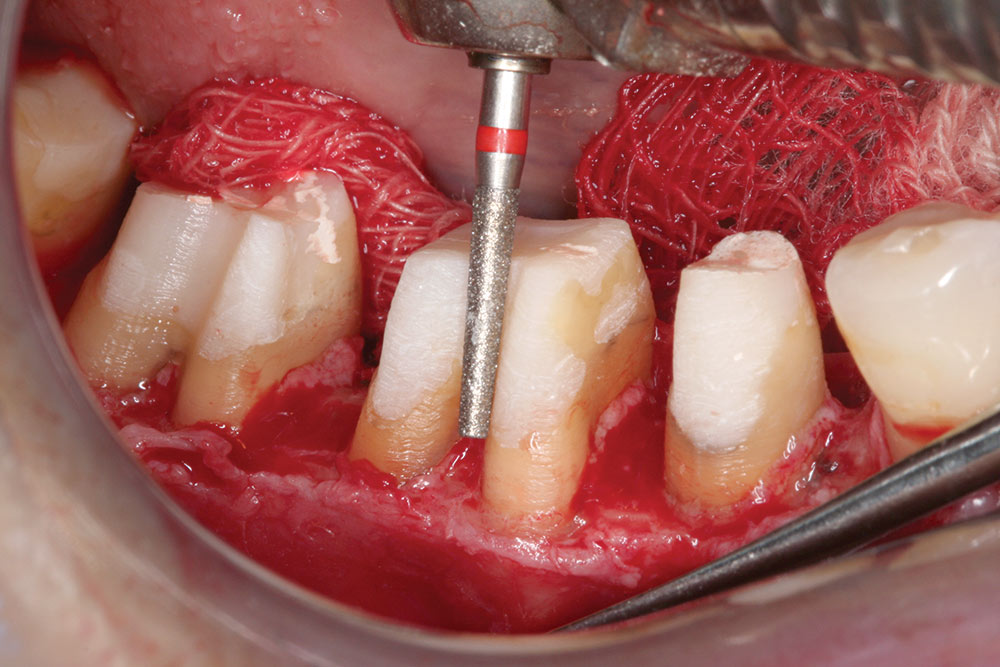

The primary objective of biologic shaping is to remove the anatomical zones where plaque accumulates and cannot be removed by simple brushing and flossing. In doing so, the patient can practice appropriate preventive procedures which can allow the teeth to survive. Without the ability to totally remove plaque from the restorations the case is destined to failure in 90% of patients.

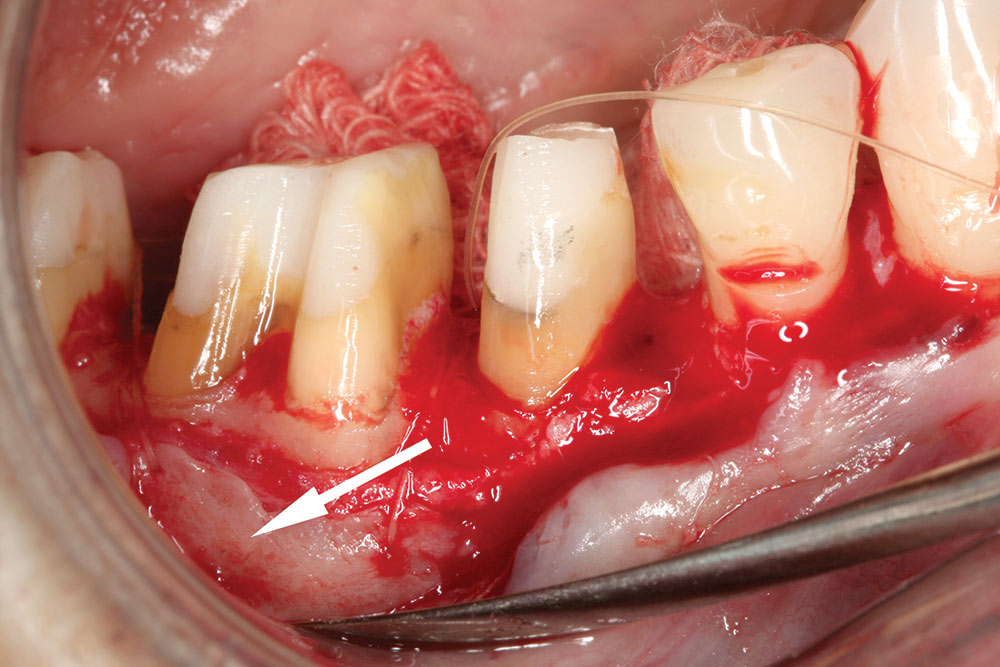

Reshaping the tooth first minimizes the amount of bone removal required. Conventional surgery relies on the position of the old margin as a guideline for osseous contouring requiring 3.0 mm from osseous crest to old margin. Biologic shaping removes the old margin and the only osseous removal necessary is for creation of the requisite parabolic architecture and providing a distance of 3.0 mm from the core buildup/sound tooth interface to the osseous crest.

Excessive bone removal causes mobility and migration. It can also open up a furcation to the point of making the tooth hopeless. The objective of periodontal therapy is to stop bone loss. If periodontal therapy requires bone loss it is counterproductive therapy.

Vital teeth must be sealed because plaque acids will dissolve the smear layer created by reshaping within five days, opening tubules for ingress of microbes that cause pulp pathology and patient discomfort.

The provisionals must be remade at four weeks using an indirect technique to avoid resin contact with immature tissue. The margins of the remade provisionals must be left 1.0–2.0 mm supragingivally so that biologic healing can take place without interference.

Post-operative sensitivity is a function of microbial invasion into the tubules. Super Seal, polycarboxylate cement, fluoride varnish and PERFECT PLAQUE CONTROL will control it.

The tissue must heal for four months from the time of surgery before final preparations can be made. The final restorative margins must be placed at or above the tissue level or the iatrogenic process that destroyed the biology of the previous case will be repeated.

The protocol demands that the restorative dentist NOT disturb the connective tissue protecting the teeth. Preparation and impression technique must be NONINVASIVE. There is no room or no need for two retraction cords. There is no need to cut the tissue either with electrosurge or a laser. It is almost impossible to miss the impression when tissue is healthy and it is left alone.

These contours must follow the barreled in furcations all the way up to the occlusal surface to allow toothbrush bristles access to remove the plaque. Dental floss will disturb all plaque colonies interproximally without a great deal of effort. The gingival embrasure spaces should be left as open as possible to provide room for interproximal brushes.

Minimized buccolingual dimension, barreled in furcation contours, sharp occlusal contacts, and diligent plaque removal will result in long term success. This statement is based on my clinical experience for over 30 years with this perio-restorative protocol.

In summary, the natural dentition is subject to disease processes that compromise the longevity of that dentition as well as the systemic health of the individual. Restorative dentistry is mandatory to replace missing and diseased tooth structure, but the health of the investing tissues after the treatment should not be compromised by such treatment. Iatrogenic dentistry is a disservice to the patient, is potentially life-threatening, and represents avenues for litigation that could prove costly to the dentist. Perio-restorative protocols that offer predictability with respect to tissue health exist and have been used successfully for over 30 years. These protocols are simple and easy to accomplish, and provide enhanced resistance to naturally occurring disease processes. All patients should be informed of the potential health complications associated with the placement of subgingival margins. Restorative dentistry should use the measures available to preserve and respect biology.

Replacing old dentistry that has severely compromised periodontal and pulp health presents one of the greatest challenges in restorative dentistry. Certainly, the option of removing the teeth and placing implants is often the easy way out from a treatment perspective on many of these cases.

Dr. Bill Strupp is a full-time practicing clinician and an international speaker acclaimed for his practical, predictable results in crown and bridge dentistry. He is a member of many prestigious organizations, including the Academy of Operative Dentistry, the American Academy of Fixed Prosthodontics, the American Prosthodontic Society, and the American Equilibration Society, as well as many others. He is an Accredited Fellow and Founding Speaker of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry. He was President and Founding Speaker of the Florida Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry. He publishes “Crown and Bridge UPDATE Interactive,” a clinical newsletter dedicated to excellence in restorative dentistry. He can be reached at strupp.com or 800-235-2515.

Seminar

Title: Simplifying Complex Cosmetic & Restorative Dentistry Date: June 12–13, 2009

Location: New York, NY USA

Seminar

Title: Simplifying Complex Cosmetic & Restorative Dentistry

Date: July 17–18, 2009

Location: Chicago, IL USA

Seminar

Title: Simplifying Complex Cosmetic & Restorative Dentistry

Date: Jan. 29–30, 2010

Location: Clearwater, FL USA

Seminar

Title: Simplifying Complex Cosmetic & Restorative Dentistry

Date: June 25–26, 2010

Location: Santa Barbara, CA USA