Altered Passive Eruption: Diagnosis and Treatment

The esthetic arena of dentistry has become an increasing portion of any clinician’s practice. An understanding of the gingival complex is a vital aspect of any restorative treatment plan. Often, the patient’s initial chief complaints are short teeth or a gummy smile. In the past, these concerns were often overlooked, or the crowns were lengthened prosthodontically.1 Patients and dentists alike are becoming aware of an increasing demand for comprehensive facial evaluations. Currently, the gingival complex is a vital aspect of any restorative treatment plan. Clinicians now are beginning to recognize the importance of the gingival complex in the treatment of short clinical crowns. The etiology of short clinical crowns can usually be subdivided into two categories: coronal destruction resulting from traumatic injury, caries or incisal attrition; and a coronally situated gingival complex resulting from tissue hypertrophy or a phenomenon known as altered passive eruption (APE).1

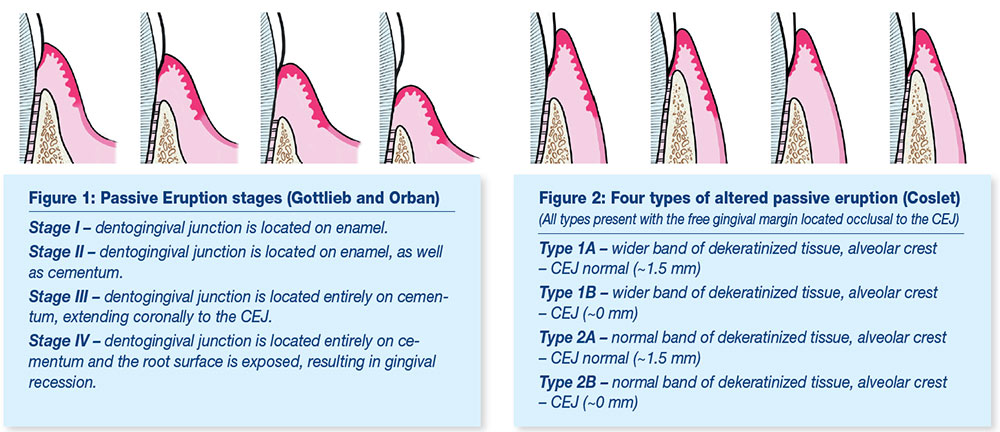

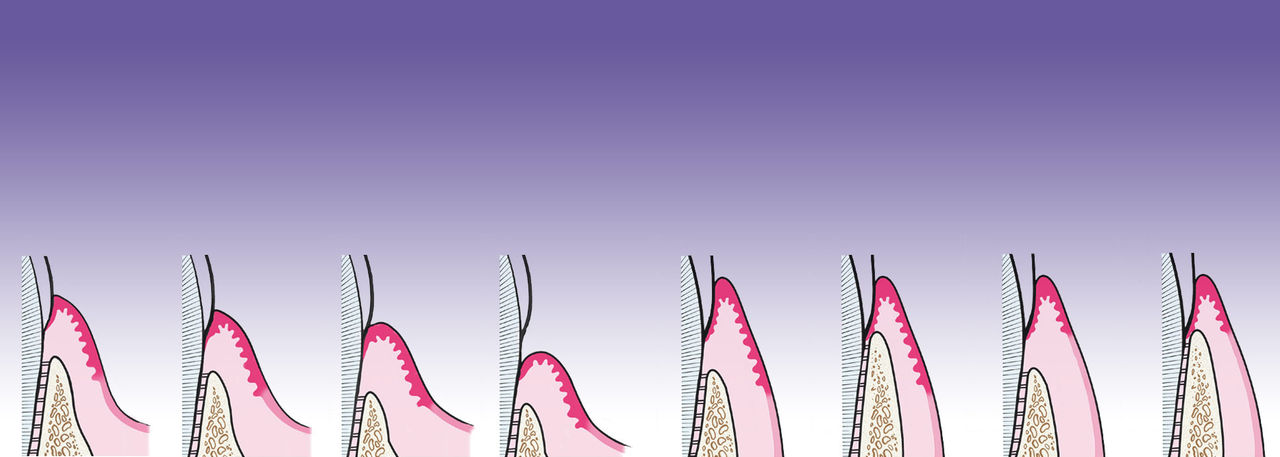

APE, also known as delayed passive or retarded passive eruption, occurs when the marginal gingiva is malpositioned incisally in adulthood on the anatomic crown and does not approximate the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ).2,3,4 Goldman and Cohen5 described altered passive eruption as a condition in which the free gingival margin fails to recede during tooth eruption to a level apical to the cervical convexity of the clinical crown. By contrast, passive eruption is a biologic process whereby tooth eruption occurs normally. During this normal tooth eruption the dentogingival junction shifts apically.6 This process occurs when active eruption is complete and may continue until the early or mid-20s of adulthood.7 At this time, the free gingival margin approximates the CEJ. Gottlieb and Orban classified passive eruption into four stages, believing this was a continuous physiologic process of tooth eruption (Fig. 1). Although some debate currently exists when passive eruption becomes pathologic, it is generally accepted that cementum exposure or gingival recession (Stage IV) is a pathologic process.

APE is one of the most commonly overlooked causes of short clinical crowns. Although literature provides limited information regarding the incidence of APE, Volchansky and Cleaton-Jones7 found that 12% of patients studied had signs of APE.8 Excessive gingival display has been estimated at 7% of men and 14% of women.2 Thus, any clinician must be cognizant of the dentogingival complex and be comfortable with the differential diagnoses of a gummy smile when striving for long-term optimal restorative esthetics and gingival health.

Gargioulo and Ainamo9,10 described the typical dentogingival relationship with the free gingival margin being located in close proximity to the CEJ. However, if APE exists, the gingival complex is situated in a more coronal position, making the CEJ difficult to detect clinically and thus displaying the pathognomonic signs of short clinical crowns and excessive gingival display.

Coslet and others11 classified APE into two case types, based on the gingival and osseous relationships. Type 1 presents with a noticeably wider band of keratinized tissue and Type 2 exhibits a smaller band of keratinized tissue falling within normal limits (Fig. 2). Types 1 and 2 each have subcategories, A and B. In the A subgroup, the osseous crest is located 1.5 mm to 2 mm below the CEJ9 (normal), while in the B subgroup, the osseous crest is found directly adjacent the CEJ.

This article presents treatment for two common types of APE found clinically. To date, no scientific literature has investigated the incidence of Coslet’s four classifications of APE. However, it is believed that Type 1B is more prevalent.1 This article presents and discusses the more common case types and the treatments employed to achieve long-term esthetic results.

Case Reports

A 26-year-old woman presented with a chief complaint of “short teeth” (Fig. 3a). After a comprehensive clinical facial and dentogingival examination, both centrals were found to have little or no incisal wear and were approximately 8.5 mm in length (Fig. 3b). The CEJ was undetectable clinically and the patient was diagnosed with APE.

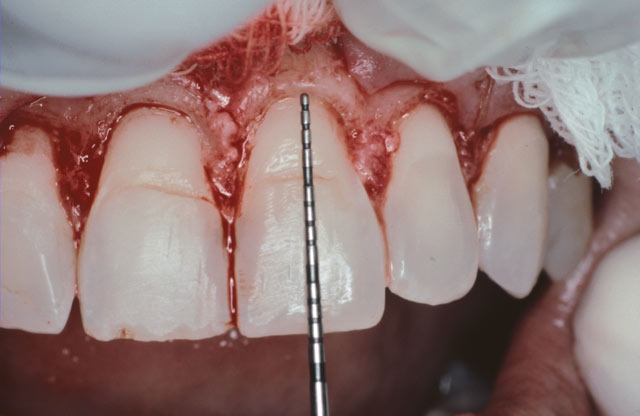

Local anesthesia (AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP) was used before further examination. Periodontal probing revealed a gingival sulcus of 3 mm, while bone sounding revealed a probing depth of 5 mm from the free gingival margin to the osseous crest, indicating a diagnosis of APE Type 1A. To achieve an ideal central incisor length of 10.5 mm,12 an esthetic crown lengthening procedure was indicated.

Currently, the gingival complex is a vital aspect of any restorative treatment plan. Clinicians now are beginning to recognize the importance of the gingival complex in the treatment of short clinical crowns.

During surgery, an inverse bevel incision following the CEJ was used. An effort was made to preserve the interproximal papillary tissues. A full-thickness flap was subsequently reflected to the mucogingival junction (MGJ). A split-thickness flap was employed beyond the MGJ. This technique allows for atraumatic mucoperiosteal flap management and mobility. As anticipated, the osseous crest levels were found to be approximately 1.5 mm to 2 mm from the CEJ (Fig. 3c), confirming the diagnosis of APE Type 1A. No osseous resection was required before flap closure. A vertical mattress technique using a 5-0 plain gut suture (Ethicon, Inc.) was used to apically reposition the gingival tissues (Fig. 3d). After six months, gingival health was optimal and an ideal clinical crown length of approximately 10.5 mm had been established (Fig. 3e).

Coslet Type 1B

A 33-year-old woman presented with a chief complaint of “I don’t like how my front teeth look” (Fig. 4a). An examination was performed and the patient was found to have excessive gingival display and short clinical crowns with a boxy appearance. Both central incisors measured approximately 8.5 mm in length (Fig. 4b). Periodontal probing revealed a gingival sulcus of 1 mm, while bone sounding revealed a probing depth of 3 mm from the free gingival margin to the osseous crest, indicating a diagnosis of APE Type 1B. An esthetic crown lengthening procedure was indicated using ostectomy and apically repositioned flap.

During surgery, an inverse bevel incision following the CEJ was used to establish ideal gingival symmetry. Subsequently a full-thickness flap was reflected to the MGJ, while a split-thickness flap was employed beyond the MGJ. Osseous crest levels were found directly adjacent the CEJ (Fig. 4c). Defective composite restorations were present on teeth #8 and #9. Approximately 1.5 mm to 2 mm of ostectomy/osteoplasty was carefully performed using rotary instruments to establish a normal osseous crest to CEJ relationship (Figs. 4d, 4e). A vertical mattress suturing technique with 5-0 plain gut sutures was used for flap adaptation (Fig. 4f). The incisors were restored with feldspathic porcelain laminate veneers. At one year, gingival tissues were healthy and an ideal clinical crown length for the central incisors was achieved at approximately 10.5 mm (Fig. 4g).

Discussion

This article presents the diagnosis and treatment of the more commonly encountered examples of APE, Types 1A and 1B. The diagnosis and treatment of APE has begun to receive the necessary attention in the dental literature.1,8 However, APE has been referred to as the “undiagnosed entity,”4 and still remains an esoteric underdiagnosed condition. In addition to limited recognition, APE may also present perio-restorative challenges. APE presents with a coronally positioned dentogingival complex. If crown lengthening is not performed before restorative therapy, subgingival margins may often lead to greater plaque accumulation, gingival inflammation and subsequent periodontal breakdown.2,13 Optimal restorative margin placement presents a functional and esthetic challenge for any dentist.

In the past, clinicians have treated APE through conventional gingivectomy procedures; recently, laser therapy14,15 has become a popular modality. Although these procedures have distinct indications,16 the more common APE examples (Type 1B) will require some ostectomy to provide a stable gingival complex and prevent gingival rebound to the preoperative levels. Employing gingival recontouring procedures as the only method of clinical crown lengthening is the result of not fully understanding the dimensions of biologic width,9 which in turn results in misdiagnosis or simply overlooking the possible diagnosis of APE. Ingber and others17 coined the term “biologic width” to describe the distance from the alveolar crest to the base to the sulcus. Commonly this distance is approximately 2 mm: 1 mm of epithelial attachment and 1 mm of connective tissue attachment. When bone sounding, a 1 mm gingival sulcus depth must be added to this dimension. When bone sounding on the facial of an incisor (i.e., tooth #8), a probing depth measurement of ≤ 3 mm must employ ostectomy and an apically repositioned flap to achieve crown lengthening, while a gingivectomy procedure is contraindicated. However, if bone sounding is >3 mm, a gingivectomy procedure can be used with success. For example, bone sounding of 5 mm may employ a 2 mm gingivectomy without gingival rebound to the preoperative levels. However, without following these specific fundamental guidelines, properly diagnosing APE and maintaining an ideal biologic width9 may be difficult to achieve. Each of these principles is important to follow when striving for optimal long-term esthetics.

The first case presented, Type 1A, demonstrates a good example of a normal osseous crest relationship requiring only an alteration of the gingival complex or an apically repositioned flap to achieve ideal gingival health and esthetics (Fig. 3a). The patient presented with a chief complaint of “short front teeth” and thus APE was included in the differential diagnosis. Bone sounding to 5 mm indicated APE and surgery ultimately confirmed the diagnosis. Restorations were not indicated and the normal dentogingival relationship was established with an apically positioned flap (Fig. 3e). By contrast, the second case, Type 1B, required both a gingival alteration and osseous recontouring to establish an ideal alveolar-dental relationship (Fig. 4b). Short clinical crowns, defective restorations, biologic width invasion and gingival asymmetry were present. Bone sounding to 3 mm indicated APE, and was confirmed during surgery. The surgical objectives were to reestablish biologic width by placing osseous crest levels 3 mm from crown margins while simultaneously providing a normal clinical crown length of approximately 10.5 mm. Following these objectives will promote functional and esthetic dentogingival relationships while simultaneously facilitating placement of supragingival2 or intracrevicular18 restorative margins (Fig. 4g).

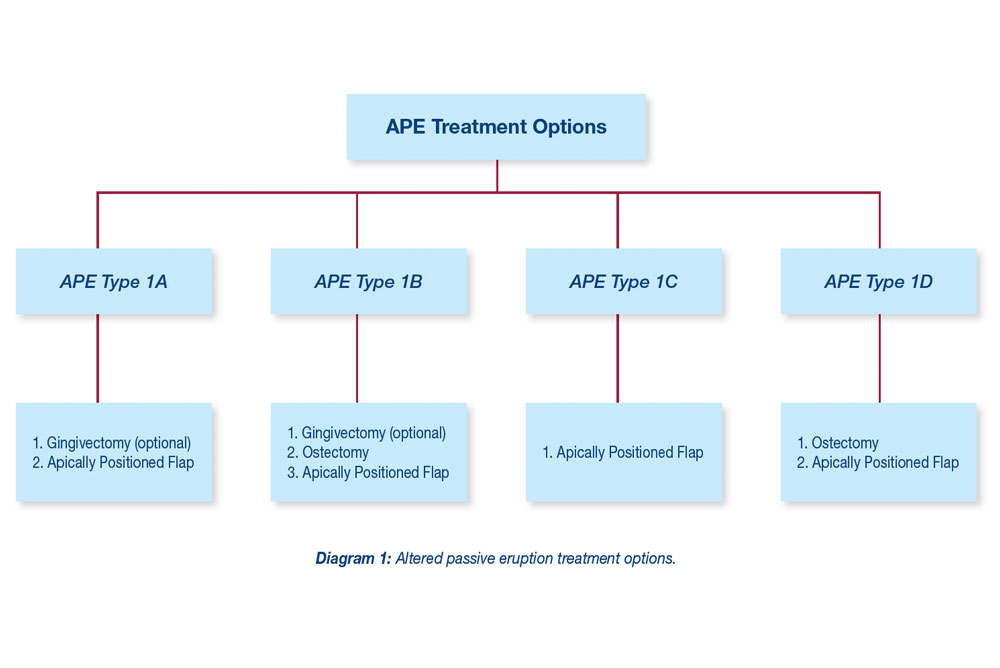

Each type of APE has specific surgical options to consider (Diagram 1). Type 1A has a greater than normal amount of keratinized tissue with a normal osseous crest-CEJ relationship. This may be treated by gingival recontouring alone and/or by an apically repositioned flap. Type 1B, however, presents with an osseous crest located at the CEJ, and usually requires gingival recontouring combined with ostectomy and an apically repositioned flap. Type 2A presents with a normal amount of keratinized tissue and has a normal osseous crest-CEJ relationship. This requires an apically repositioned flap rather than a gingivectomy to preserve adequate keratinized tissue. Type 2B, on the other hand, has an excessive osseous crest and requires ostectomy combined with an apically repositioned flap to preserve adequate keratinized tissue.

Although each classification of APE requires specific surgical guidelines to establish an ideal dentogingival relationship, any surgeon is faced with two basic options:

- To alter the gingival complex alone, or

- To alter the gingival complex and/or remove bone.

Thus, any surgeon must ultimately decide to either include ostectomy or not. Although the osseous architecture and correct choice of surgical procedure is difficult to establish without reflecting a mucoperiosteal flap, bone sounding has proven to be a valuable adjunct when indirectly locating osseous crest levels. Bone sounding includes administering local anesthesia, inserting a periodontal probe positioned within the sulcus, and then pressing the probe through the junctional epithelium and connective tissue to the crest of bone. This procedure provides a method of bone mapping and will supplement diagnostic information. However, bone-sounding data only represents specific points of the osseous crest and thus is limited in providing a precise replica of osseous architecture. Dento-alveolar anomalies and root concavities may also go undetected. To reduce touch-up procedures and gingival recontouring, surgically reflecting a mucoperiosteal flap is the most predictable method of determining osseous architecture to achieve optimal dentogingival relationships.

Summary

It is important to consider APE in the differential diagnosis any time the chief complaint resembles a “gummy smile” or “short front teeth.” Short clinical crowns may often be a result of APE, a condition that is commonly overlooked. Fundamental knowledge of the dental and soft tissue relationships must be employed when diagnosing and treating APE. Establishing proper crown length and maintaining biologic width are critical for gingival health and restorative procedures.

If APE is suspected, bone sounding is a valuable diagnostic tool, although surgical intervention may provide the most reliable method to establish a harmonious perio-restorative interface.

If APE is suspected, bone sounding is a valuable diagnostic tool, although surgical intervention may provide the most reliable method to establish a harmonious perio-restorative interface. Considering the esthetic emphasis in dentistry today, it is important to properly recognize APE during any dentofacial examination and strive for optimal gingival health and esthetics.

Robert P. Pulliam, DMD, M.S., RPh, is in private practice and may be contacted by phone at 615-297-8973. Daniel J. Melker, DDS, is also in private practice and may be reached by calling 727-725-0100.

Acknowledgment

The restorations presented in this article were performed by Bill Strupp, DDS, Clearwater, Florida.

Reprinted from Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice: Pulliam RP, Melker D. Altered passive eruption: diagnosis and treatment. 2002;8(4):20-30. Copyright ©2002, with permission from AEGIS Publications, LLC.

References

- ^Dolt AH 3rd, Robbins JW. Altered passive eruption: an etiology of short clinical crowns. Quintessence Int. 1997 Jun;28(6):363-72.

- ^Dello Russo NM. Placement of crown margins in patients with altered passive eruption. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1984;4(1):58-65.

- ^Wolffe GN, van der Weijden FA, Spanauf AJ, de Quincey GN. Lengthening clinical crowns—a solution for specific periodontal, restorative, and esthetic problems. Quintessence Int. 1994 Feb;25(2):81-8.

- ^Evian CI, Cutler SA, Rosenberg ES, Shah RK. Altered passive eruption: the undiagnosed entity. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993 Oct;124(10):107-10.

- ^Goldman HM, Cohen DW. Periodontal therapy. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1968.

- ^Gottlieb B, Orban B. Active and continuous passive eruptions of teeth. J Dent Res. 1933;13:214.

- ^Volchansky A, Cleaton-Jones P, Retief DH. Delayed passive eruption—a predisposing factor to Vincent’s infection? J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1974;29:291-4.

- ^Weinberg MA, Eskow RN. An overview of delayed passive eruption. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2000 Jun;21(6):511-4, 516, 518 passim; quiz 522.

- ^Gargiulo AW, Wentz FM, Orban B. Dimensions and relations of the dentogingival junction in humans. J Periodontol. 1961;32:261-7.

- ^Ainamo J, Löe H. Anatomical characteristics of gingiva. A clinical and microscopic study of the free and attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1966 Jan-Feb;37(1):5-13.

- ^Coslet JG, Vanarsdall R, Weisgold A. Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult. Alpha Omegan. 1977 Dec;7(37):24-8.

- ^Ash MM Jr. Wheeler’s dental anatomy, physiology and occlusion. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1984. p. 120.

- ^Flores-de-Jacoby L, Zafiropoulos GG, Ciancio S. Effect of crown margin location on plaque and periodontal health. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1989;9(3):197-205.

- ^Cortex M. Nd:YAG laser-assisted gingivectomy, bleaching, and porcelain laminates, Part 2. Dent Today. 1999;18(4):52-5.

- ^Russo J. Periodontal laser surgery. Dent Today. 1997 Nov;16(11):80-1.

- ^AAP position paper. Lasers in periodontics. J Periodontol. 1996;67:826-30.

- ^Ingber JS, Rose LF, Coslet JG. The “biologic width”—a concept in periodontics and restorative dentistry. Alpha Omegan. 1977 Dec;70(3):62-5.

- ^Maynard JB, Wilson RDK. Physiologic dimensions of the periodontium significant to the restorative dentist. J Periodontol. 1979;50:170-4.