Elective Cosmetic Dental Treatment: One Dentist’s Philosophy Concerning ‘When to Treat’

“Conservatism as a philosophy of treatment has also come ‘full circle.’ As Shavell once said, ‘Many teeth are sacrificed upon the altar of false conservatism.’ That statement was never more true than today.”

A “Moral Dilemma”?

It is a wonderful time to be practicing dentistry! As advances in dental materials and techniques continue to unfold, the benefits to the end user, the patient, are greater now than at any time in the history of our profession. Dentistry is evolving from a “reactive profession” with the mindset “it can’t be fixed until: 1 the disease has progressed far enough,2 it breaks” to a “proactive profession” where prevention and minimally invasive techniques are prevalent.

Conservatism as a philosophy of treatment has also come “full circle.” As Shavell1 once said, “Many teeth are sacrificed upon the altar of false conservatism.” That statement was never more true than today. We no longer have to remove healthy tooth structure for the structural requirements of the restorative material as we did for cast gold and dental amalgam. Adhesive technology has advanced so far that we can micro-mechanically bond a “jigsaw puzzle piece” of tooth-colored restorative material to tooth substrate that will wear favorably and support remaining natural tooth structure. So, where is the dilemma?

The ability to predictably bond very thin pieces of tooth-colored restorative material to teeth and expect excellent long-term results has created a new area in the practice of dentistry — that of elective cosmetic treatment. Over the last 20 or so years, materials and technologies have continued to improve such that today, many procedures whose longevity was felt by the “old school” to be a compromise, have proven to be excellent, clinically viable, long-term treatment options. Teeth can now be “resurfaced” with tooth-colored restorative materials requiring very little tooth preparation. The “lamination effect”2 by virtue of adhesive bonding technology allows the dentist to add a brittle restorative material of minimal thickness to the surface of the tooth which will not break under normal masticatory function.

Hence, patients who are not happy with the smile Mother Nature provided can elect to have a “smile makeover,” correcting esthetic problems associated with tooth shape, position, size and color. For many years, patients had to live with esthetic problems that were tooth-related. Orthodontics can straighten teeth, but cannot alter malformation or problems associated with tooth color. The psychologic ramifications to the patient of an unesthetic smile are only beginning to be understood and validated.

Some dentists still believe that it is a “violation of the Hippocratic Oath” to disturb “healthy” tooth structure, even if the patient is unhappy with their esthetics, and that we should “talk them out of elective treatment.” In this day and age, such backward thinking is unnecessary. Just ask the thousands of happy patients who have “sacrificed” a few tenths of a millimeter of tooth structure whether the dramatic esthetic changes achieved were worth the risk. And, that is exactly what it comes down to: “risk versus benefit.” Is the risk associated with the minimal loss of tooth structure worth the benefit of a long-term cosmetic change for the patient? For many patients, elective cosmetic dentistry can be a life altering experience altering those who were not fortunate enough to be born with “perfect teeth,” the smile they have always wanted. The following is just such a case.

Patient History: The Anatomy of a Smile

The patient was a 21-year-old female who, for her entire life as she remembers it, was ashamed to smile. She had a congenital condition called “microdontia” which caused much of her permanent dentition to be malformed and so small that she had diastemata between most of her teeth from the molar region forward. The buccal cusps of her canine and premolar teeth appeared to be very sharp and pointed. Facially, this young woman appeared to have the teeth of a child (Figs. 1–3). As far as her occlusion was concerned, she had a Class I molar relationship and functioned in a very nondestructive chewing pattern. She exhibited no muscle tenderness or temporo-mandibular joint dysfunction. Aside from a few small direct dental restorations, her dental health history was unremarkable. Most dentists would consider that she had “good teeth” from a disease perspective. However, to the patient, her teeth were anything but “good.” The maxillary and mandibular arch form was good and the spacing was well divided (Figs. 4, 5). It was almost as if the teeth had been orthodontically positioned to equalize the spacing. The interarch distance was minimal, which meant the preparation for any full coverage restorations would yield a stump with minimal axial height and retention after occlusal reduction. The problem was to restore esthetic beauty with as little tooth reduction as possible and without altering the occlusal vertical dimension. To complicate things further, the patient had to travel from Texas to North Carolina for her treatment.

After a local dentist in Texas had taken a full mouth set of radiographs and preoperative study models, it was determined that all teeth from the premolar region of both arches would require treatment. The maxillary and mandibular molars would remain untreated and maintain the preoperative occlusal vertical dimension. Due to the short cervicoincisal height of the clinical crowns, it was recommended that the patient have surgical crown lengthening by a local periodontist to gain as much axial height as possible. The tissues were allowed to heal for six months prior to the commencement of restorative therapy. The operative plan was to prepare the anteriors and bicuspids on both maxillary and mandibular arches, take master impressions, interocclusal records, a facebow transfer, and fabricate chairside provisional restorations based on a preoperative laboratory wax-up (Fig. 6). One month later, the patient would return for delivery of the restorations, with a three-day follow up and necessary occlusal adjustment prior to returning to Texas. A local dentist planned to follow the case and provide necessary follow up care.

Smile Transformation: How Important Are Teeth?

The methodology of tooth preparation was to create 360-degree “minicrowns” for the six maxillary anterior teeth. It was felt that in order to maximize the gingival esthetics and to create proper facial and lingual embrasures, 360-degree preparation of these teeth would be necessary. However, the amount of tooth reduction incisally and axially would be minimal, about five-tenths of a millimeter. In actuality, one merely needed to remove the heights of contour and create a finish line for the laboratory in a similar fashion to preparing pedodontic teeth for stainless steel crowns. The mandibular anterior teeth, being more closely spaced, would be prepared for three-quarter “wrap around” porcelain veneers.

Preparation design for the premolar teeth needed a bit more “creativity.” The plan was to have functional contacts on enamel and not to reduce the occlusal surfaces. Yet, some interproximal caries existed in some areas and veneering only the facial surfaces would leave poorly contoured lingual embrasure areas (shelves) with the potential to trap food. A modification of the onlay veneer preparation3 was planned that would restore lingual embrasure contours, remove decay and create resistance to facial displacement, yet leave the occlusal enamel surface intact. This has been termed by the author the “Lebda modification” for the onlay veneer (named for the first patient on whom this design was used).

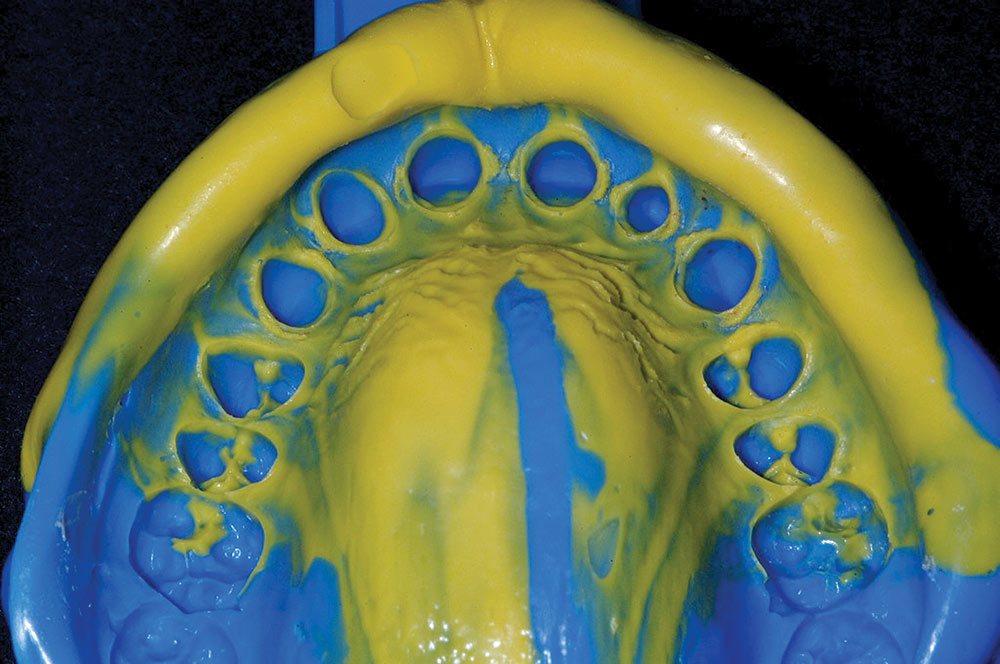

The distance (diastema) between the premolar teeth was equally divided and closed by the adjacent proximal restored surfaces. The prepared teeth are shown in Figure 7. Following tooth preparation, a periodontal probe was used to measure proximal sulcus depth of the maxillary anterior teeth. About three millimeters of sulcus depth was measured on average. A diode laser (ezlaze™ [BIOLASE Technology, Inc.; Irvine, Calif.]) was used interproximally to create small triangular spaces in the soft tissue to give an illusion of facial interdental papillary tissue (Fig. 8). By creating this space and slightly lowering the interproximal margin, the ceramist could create an emergence profile that could push the interproximal tissues together slightly and close the space. Also, this procedure would help the ceramist prevent “ledging” of the ceramic material to eliminate “black triangles.” Aside from these interproximal areas, all finish lines of tooth preparations were positioned at the crest of the gingival tissue, or slightly supragingival. Master impressions (Fig. 9) were made of both arches without the need for gingival retraction or hemorrhage control.

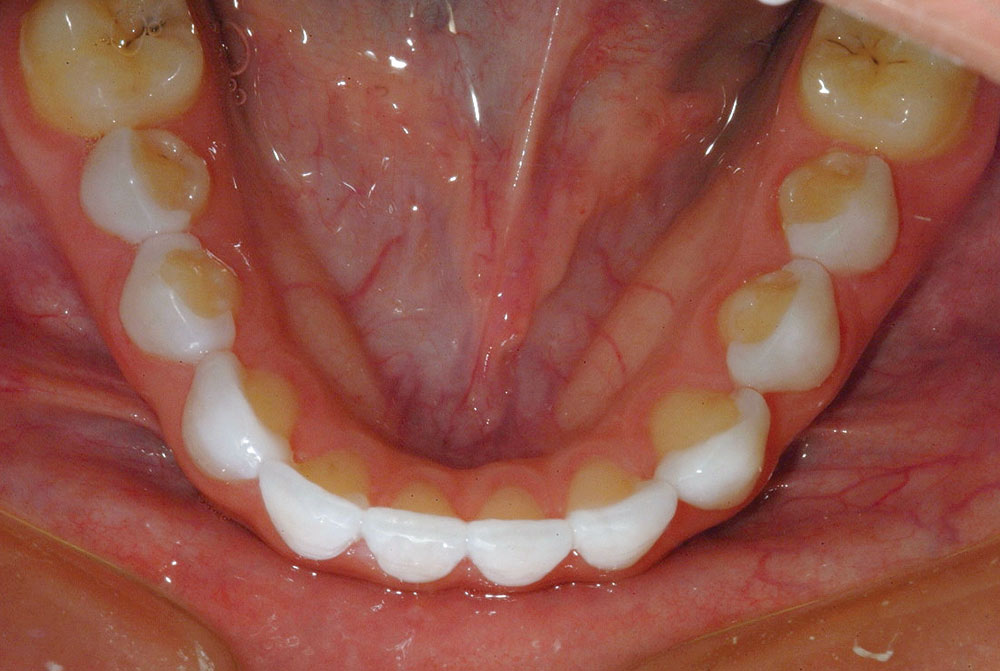

A hard acrylic index (LuxaBite [Zenith/DMG; Englewood, N.J.]) was taken in the anterior region with the molar teeth in proper centric position. A facebow transfer was also made relating the positions of the upper preparations to the patient’s maxillary base. Bis-acrylic provisional restorations were fabricated with temporary material (Venus® Provisional Material [Heraeus Kulzer; South Bend, Ind.]) using a clear stent derived from the stone model replica of the laboratory wax-up. The provisional restorations were luted in place using flowable resin (Venus Flow [Heraeus Kulzer]) and the “spot etch” technique4 excess resin was cleared away using a no. 2 Keystone brush (Patterson Dental; St. Paul, Minn.) prior to light-curing. The margins were finished with a high-speed 30-fluted composite finishing bur (Brasseler USA; Savannah, Ga.). Polishing of the bis-acrylic provisional restorations was performed using rubber abrasives followed by a polishing brush (Enhance® Points [DENTSPLY Caulk; Milford, Del.]) and Occlubrush® (Kerr-Hawe; Orange, Calif.). The final provisional restorations are shown in Figures 10 and 11. Note the incredible transformation of this “little girl” into a grown woman. The esthetics of a beautiful smile are indeed empowering.

Delivery of the Ceramic Restorations: The Moment of Truth

The patient had requested like so many other patients these days to have a “white and bright” smile. The challenge with these cases is to create natural shape and contour that is brighter in value than natural teeth, yet has the same optical properties, incisal translucency and polychromacity as teeth in the natural range of color. The ceramic restorations were fabricated from Venus Porcelain (Heraeus Kulzer) (Figs. 12, 13). The manufacturer reports that the patented synthetic quartz from which Venus Porcelain is made creates dental restorations with the natural elegance of natural tooth structure.

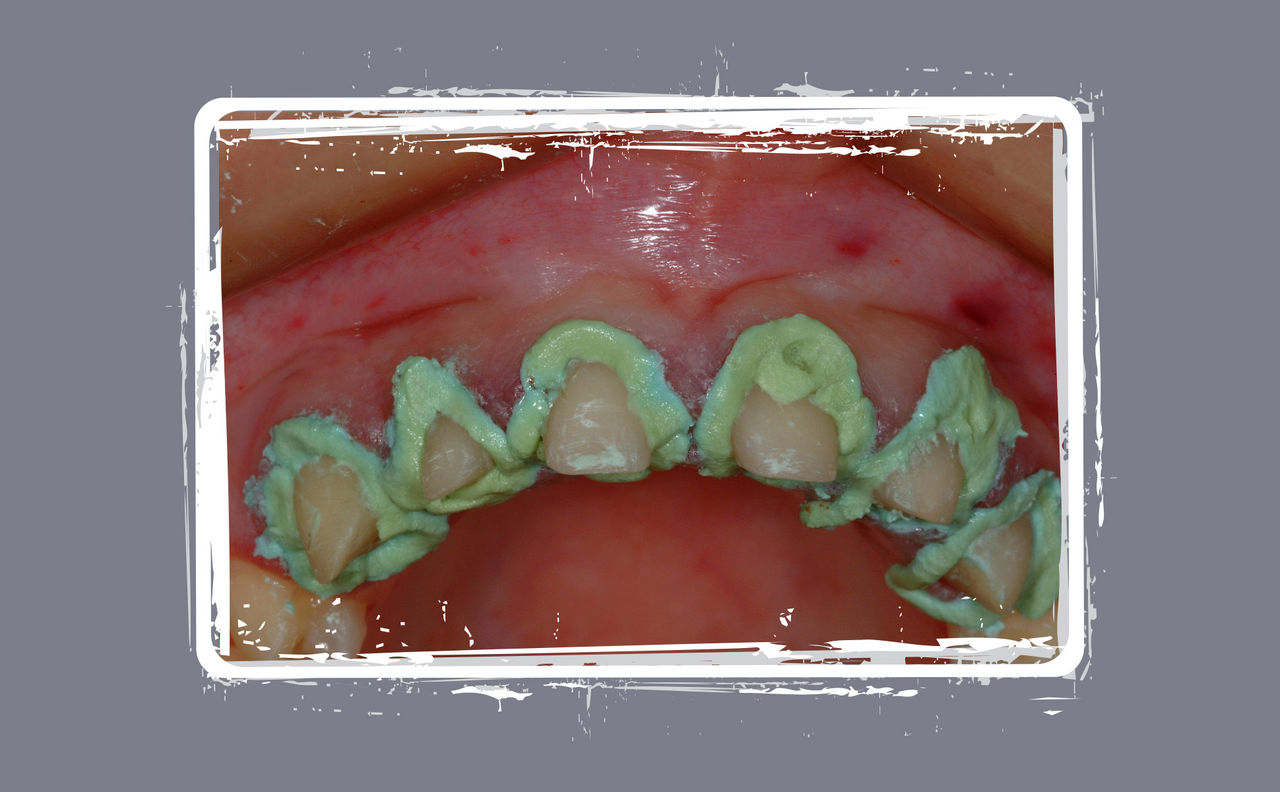

The patient was scheduled for delivery of her restorations approximately four weeks after the preparation appointment. Upon removal of the provisional restorations, the soft tissue environment was “less than ideal” for bonding restorations. Generalized sulcular reddening of the epithelium was noted with some tissue migration over marginal areas (Fig. 14). Creating a suitable environment for bonding was simply accomplished through the use of Expasyl™ (Kerr Corporation). Expasyl was syringed around each preparation and gently packed apically with a moist cotton pledget (Fig. 15). It was allowed to sit for two minutes, and then rinsed away with an air-water spray (Fig. 16). The combination of sulcular drying, hemostasis and tissue deflection now created a perfect environment to bond ceramics without the risk of fluid contamination. The maxillary ceramic restorations were tried in individually for marginal evaluation, then collectively for fit and contact verification. Next, they were all luted using a clear, dual-cured resin cement (NX3® Nexus Third Generation [Kerr Corporation]).

The same regimen was performed for the mandibular restorations as well. After cementation centric occlusion was adjusted, as needed, using articulation paper (AccuFilm® II [Parkell; Edgewood, N.Y.]) to identify occlusal contacts. Next, lateral and protrusive excursions were checked and adjusted. All adjusted areas were then polished using porcelain polishing points (Brasseler USA). The patient was restored with anterior guidance and canine disclusion (Figs. 17–21).

Some dentists still believe that it is a “violation of the Hippocratic Oath” to disturb “healthy” tooth structure, even if the patient is unhappy with their esthetics, and that we should “talk them out of elective treatment.”

Epilogue

Conservative elective cosmetic dentistry and the right of the dental patient to seek and receive treatment

The case that has been presented is clearly one that has made a major life-altering change for the patient. The positive psychological ramifications of her new smile will be enjoyed for many years to come. We all have the same potential to profoundly impact our patient’s lives by improving self-image and self-esteem through the delivery of cosmetic dental procedures.

There are some in our profession, however, that view elective cosmetic dental procedures as “unethical” and “unnecessary.” Who really should decide when such treatment is justified? How wide must the diastema be, or how unesthetic the smile? In this modern era of dentistry, we now have the responsibility to not only diagnose and treat dental disease, but to offer solutions for cosmetic dental problems as well. Remember, it’s only a “good tooth” if the patient is happy. As a profession we must remember, we treat not only teeth, but also the person to which they belong (Figs. 22, 23).

To contact Dr. Robert Lowe, call 704-364-4711, email boblowedds@aol.com or visit destinationsmile.com.

References

- ^Shavell HM. Lecture for Honors Day at Loyola University School of Dentistry, April 1980. Nash RW. Subtle changes, brighter smiles with porcelain veneers. Compendium. 1994;15(1):8-12.

- ^Lowe RA. The contact lens inlay/onlay veneer: a combination of structural strength and esthetic beauty. Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice. 2001 July;5(7):50-5.

- ^Lowe RA. Tips for successful provisional restorations—every time for every case. Dental Products Reports. 2002 Oct:68-72.

- ^Lowe RA. Matching existing natural teeth with ease and predictability in the esthetic zone. Contemporary Esthetics and Restorative Practice. 2003 Dec;6(12):54-9.

Reprinted with permission of Oral Health Journal (July 2008). Copyright ©2009 Oral Health Journal.