Patients Who Make a Dentist Most Anxious About Giving Injections

Abstract

The patient is not the only person in the dental operatory who may be feeling anxious about injections. A questionnaire mailed to 3,000 alumni of a California dental school to study the effects on dentists of administering local anesthesia shows that they, too, can be anxious during the procedure. Of the 3,000 questionnaires sent out, 711 valid ones were returned. This paper analyzes the answers of 545 respondents to the open-ended question: “Is there one type of patient that seems to make you the most anxious about giving injections? If so, please describe this type of patient.” Two-thirds of the responses to this question described anxious patients as the main source of the dentist’s anxiety. The next most frequent response (16%) identified children as the main source of anxiety. Six percent of the dentists wrote that no particular type of patient bothers them when giving injections.

It is well known that dental practice is stressful to the dentist.1,2,3 It often involves anxious patients who anticipate pain during the course of treatment. In analyzing the answers on 3,700 questionnaires received in 1981, Dunlap4,5and Stewart4,5 found that the patient’s display of pain and fear most commonly causes stress to the dentist. O’Shea and colleagues6 polled almost 1,000 dentists on 25 possible stressors and found that dealing with anxious patients and causing pain in patients were two of the most prominent factors in dentists’ stress levels.

In 1985, Render7 evaluated the self-reported immediate and long-term reactions of 181 dentists to the observation of patient pain. He found that patient pain can have profound effects on the well-being of the dentist. Borea, et al.8 measured the changes in blood pressure and heart rate of six dentists performing various difficulties of extractions on groups of anxious and calm patients. They found that patient anxiety, more than extraction difficulty, had an adverse effect on the dentists’ cardiocirculatory function.

Other studies have looked at the role potential patient pain from receiving injections has on a dentist’s heart function. In a paper published in 1983, Moore and Liggett9 studied 26 dentists and found a significant elevation in their heart rates when measured one minute before and 15 seconds after they administered inferior alveolar injections. Rosenberg10 monitored the heart rate of 15 oral and maxillofacial surgeons and found them to be elevated when local anesthesia was administered. Pre-induction heart rates were 20% higher than baseline heart rates. The rates gradually increased as the dentists administered local anesthetic and reached a maximum of 35% over baseline during the first minute following the injection. Heart rates returned to baseline levels within three minutes after the injection.

These studies document through self-reporting and measured physiologic parameters that the anxious patient and the possibility of causing patient pain during an injection often illicit an anxious response from the dentist. The purpose of this study was to focus on the type of patient that makes the dentist most anxious about giving injections. An open-ended question was created to prompt specific, individualized responses: “Is there one type of patient that seems to make you the most anxious about giving injections?”

Method

A survey was mailed to 3,000 alumni of University of the Pacific School of Dentistry. The questionnaire was pretested on 36 students and hygienists enrolled in CE courses on overcoming problems in local anesthesia. In its final form, the survey was included in a standard quarterly mailing to alumni. The recipients were asked to anonymously complete the four-page, 21-item questionnaire and return it by mail. The return rate was 24%, which yielded 711 valid forms.

Survey Design:

- 4 pages, 21 questions

Time to Complete:

- Approximately 10 minutes

Return Rate:

- 711/3,000 or 24%

Respondent Profile:

- Sex: 84% male, 16% female

- Age: Range 23–71, mean 42.6 years

Years in Practice:

- Range 1–54, mean 20.4 years

Type of Practice:

- 87% general

- 10% specialty

- 67% solo practice

- 21% group practice

The survey was broad-based, canvassing topics of patient and dentist level of discomfort during various injections, measures of success in obtaining local anesthesia, concerns about performing local anesthesia, and immediate and long-term effects of administering anesthesia. It included two open-ended short-answer questions. One of the open-ended questions, “Do you have any other comments related to the impact of giving local anesthesia?” was answered by 194, or 31%, of the respondents. The other open-ended question was: “Is there one type of patient that seems to make you the most anxious about giving injections? If so, please describe this type of patient.” There was a very high rate of response by dentists to this question.

Results

Seventy-six percent of the 711 dentists responded to the question: “Is there one type of patient that seems to make you the most anxious about giving injections? If so, please describe this type of patient.” It elicited 545 answers, which were often emotionally charged and contained a specific patient factor.

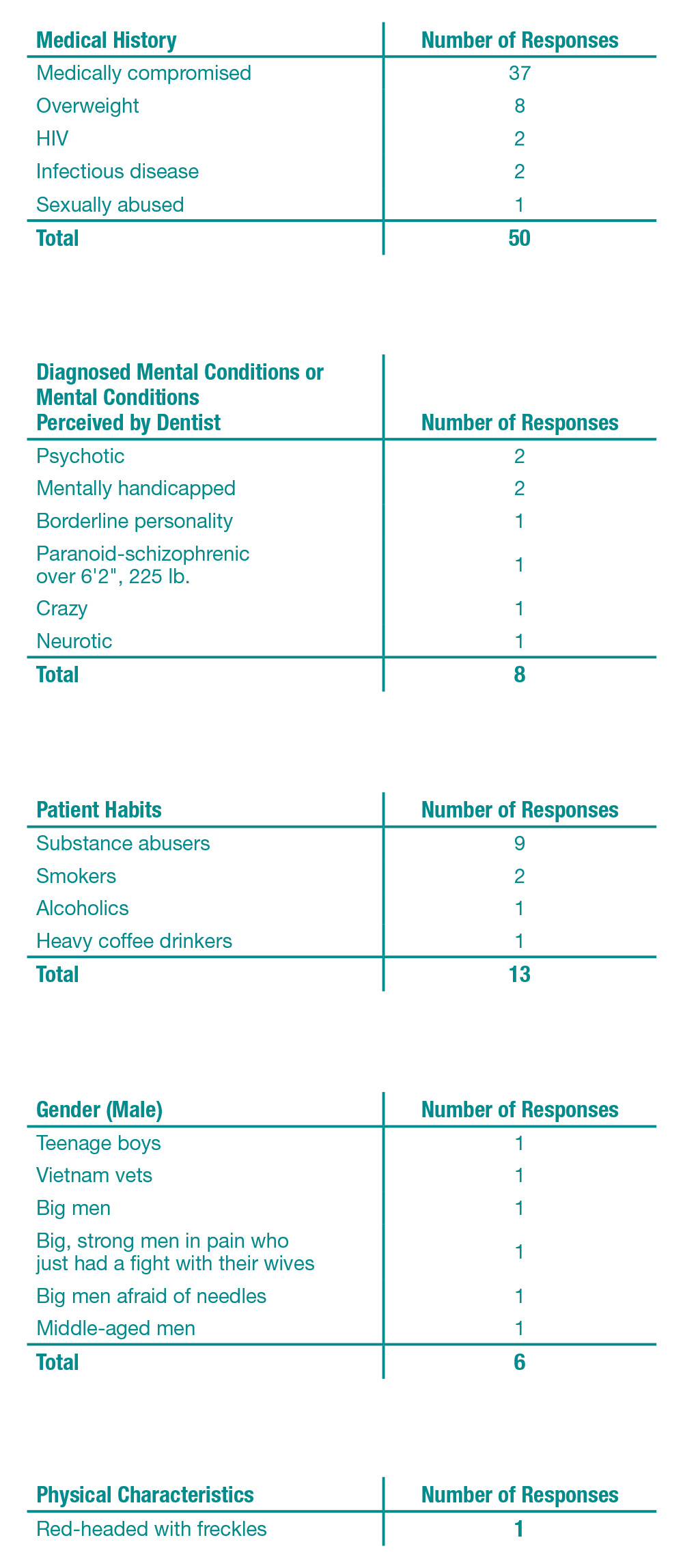

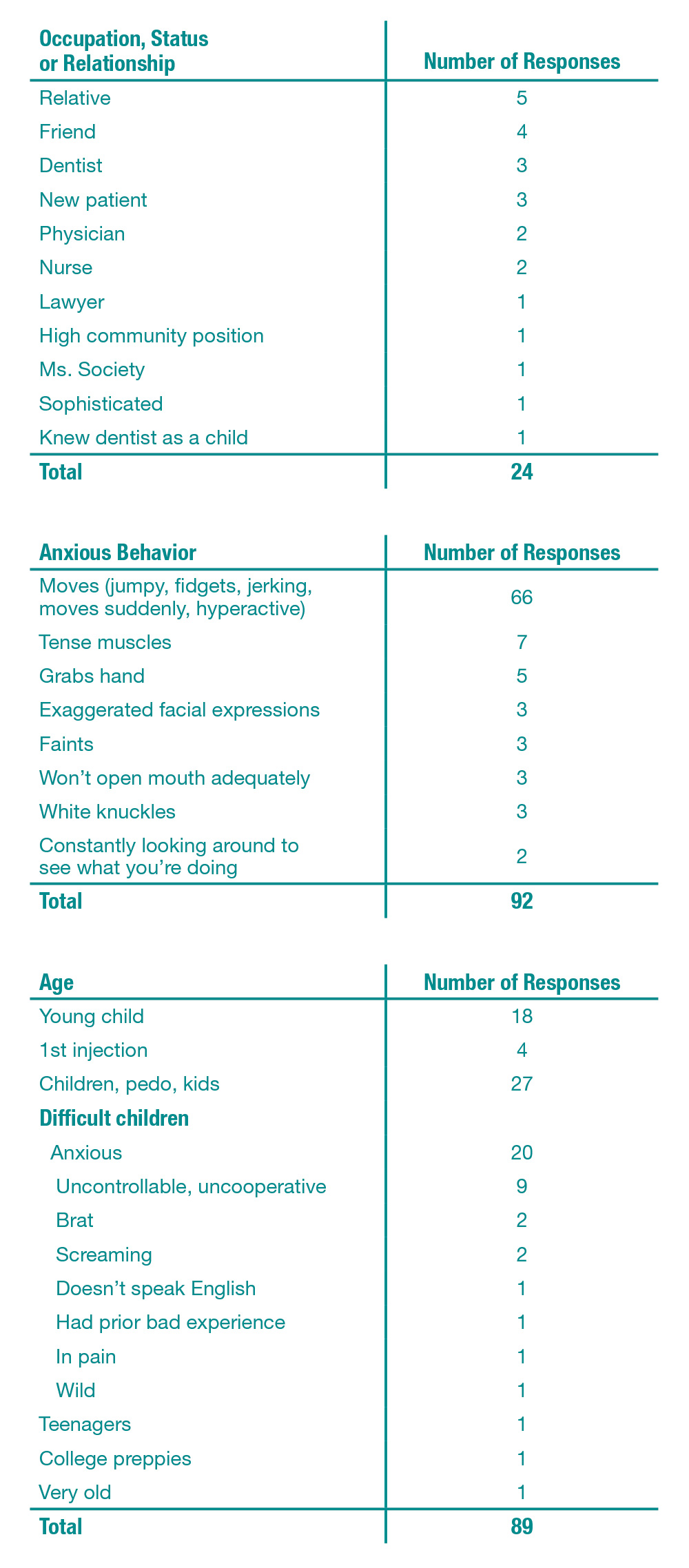

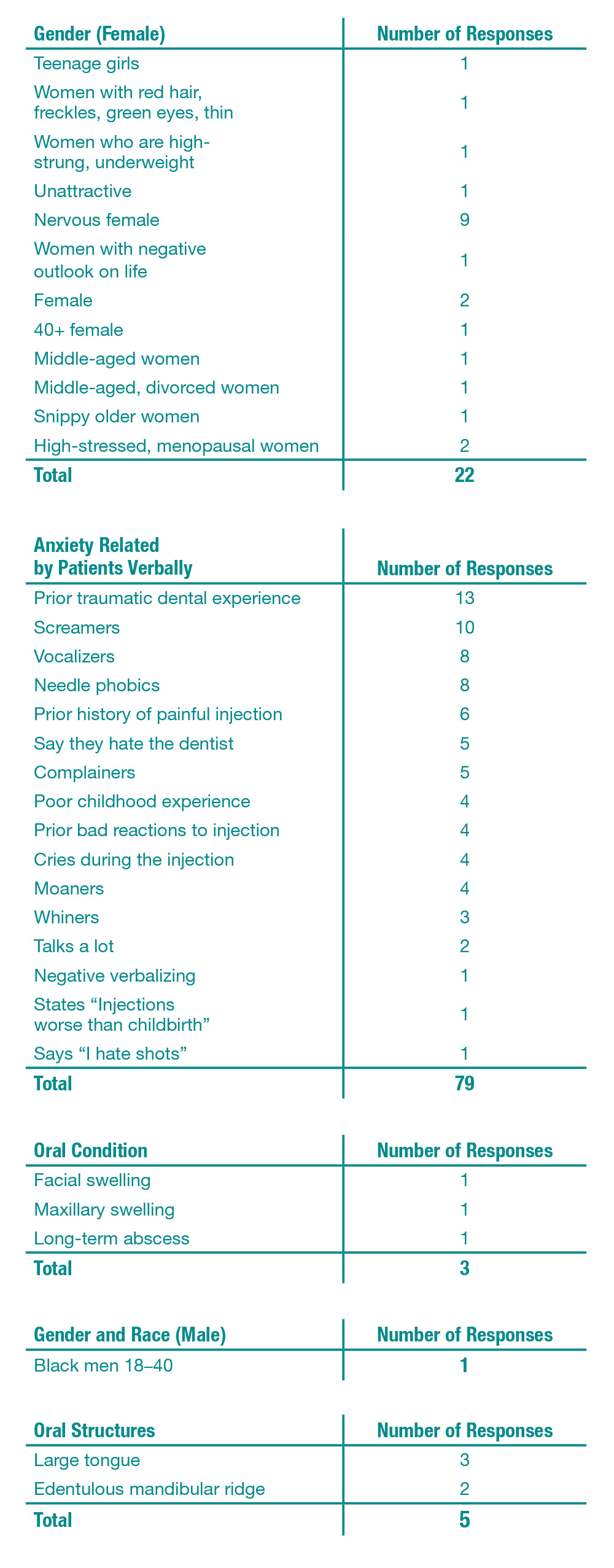

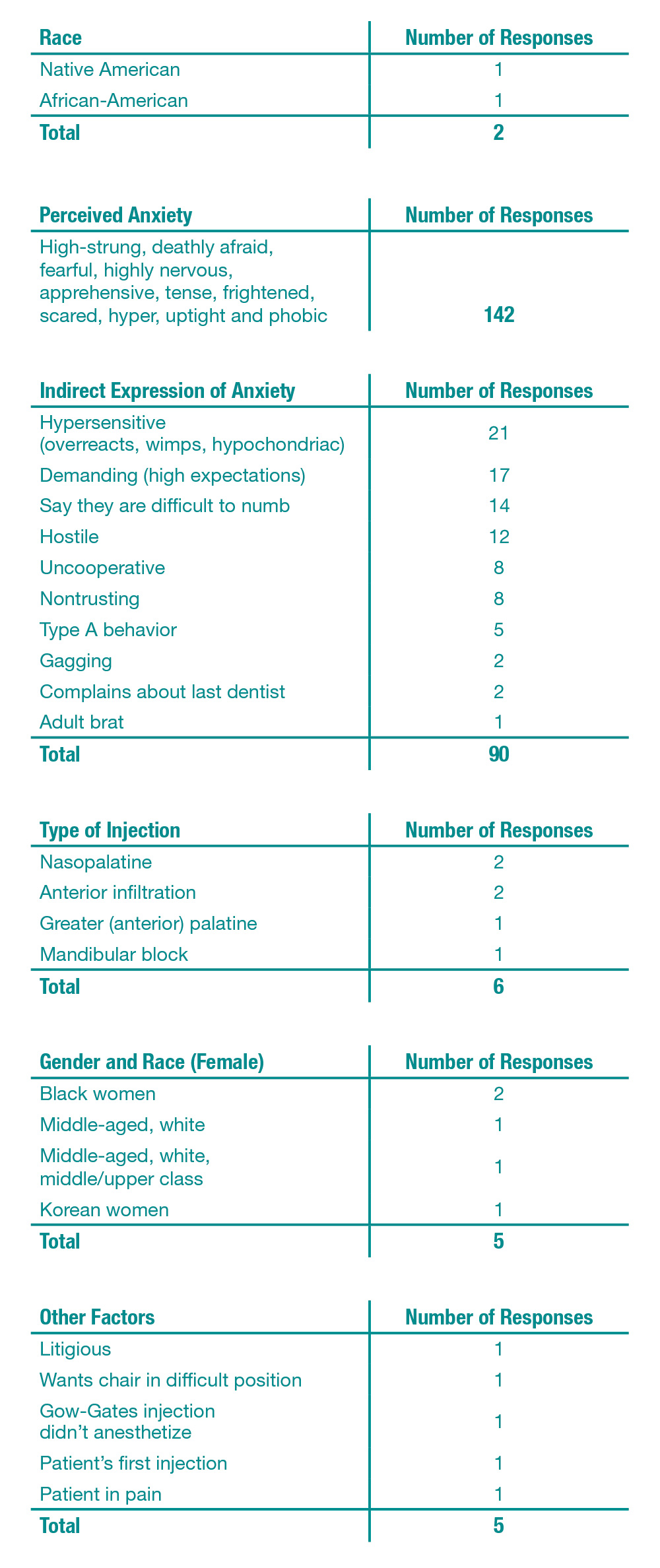

These 545 respondents wrote 676 answers, which included 141 different responses. The 141 responses have been grouped together based on patient factors, such as medical findings, social status, gender and age. Listed in Table 1 is the authors’ subjective groupings by subject of the exact answers as given by the responding dentists. There are certainly other ways the data can be organized.

Table 1

Types of patients cited by 545 surveyed dentists, in their own words, as giving them the most anxiety in giving an injection, grouped by subject response.

Of the respondents, 33 stated that no particular type of patient causes them anxiety in giving injections.

Discussion

As the other studies mentioned have found, it is the nervous patient who makes the dentist the most anxious about giving injections. Maze11 has stated anxiety is contagious. Table 1 lists some of the many ways a patient displays anxiety to the dentist. These actions or displays then make the dentist anxious.

Three of the entries in the section of Table 1 labeled “Indirect Expression of Anxiety” have been listed in the literature as those of a fearful patient. Klepac, et al.12 found that patient problems with gagging may be due to fear. Mazey11 indicates a fearful patient may be aggressive (hostile entry), argumentative and acting obsessive (demanding entry) to delay the heightened anxiety they will experience when their dental treatment begins.

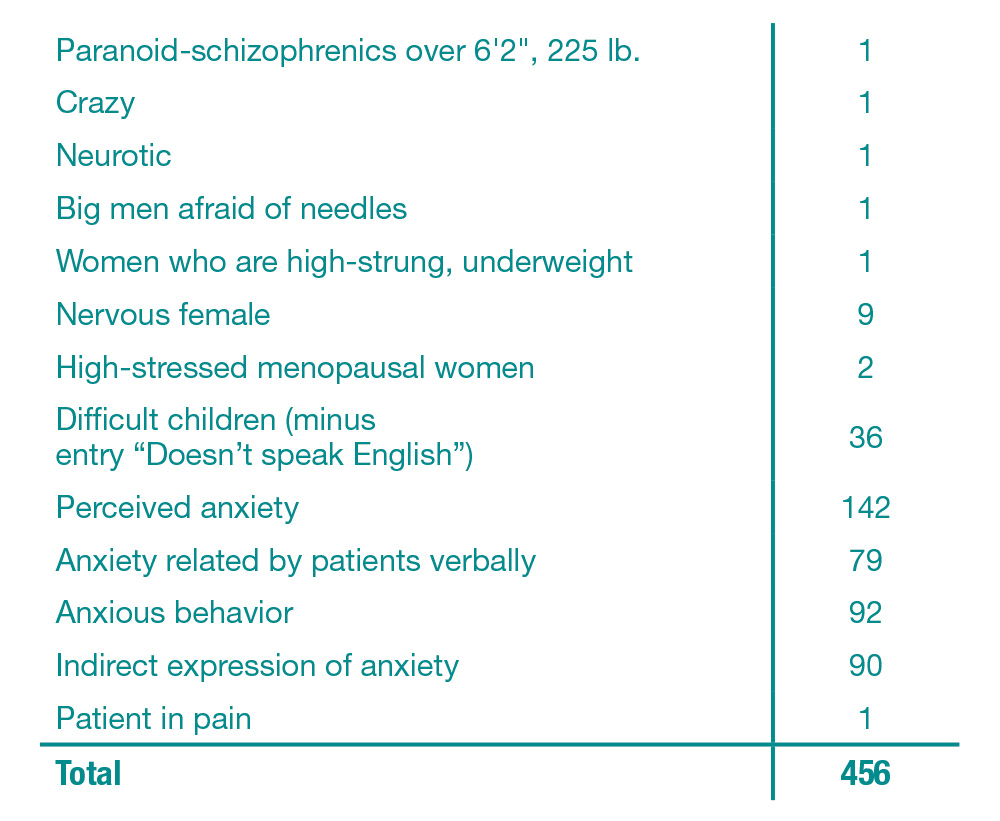

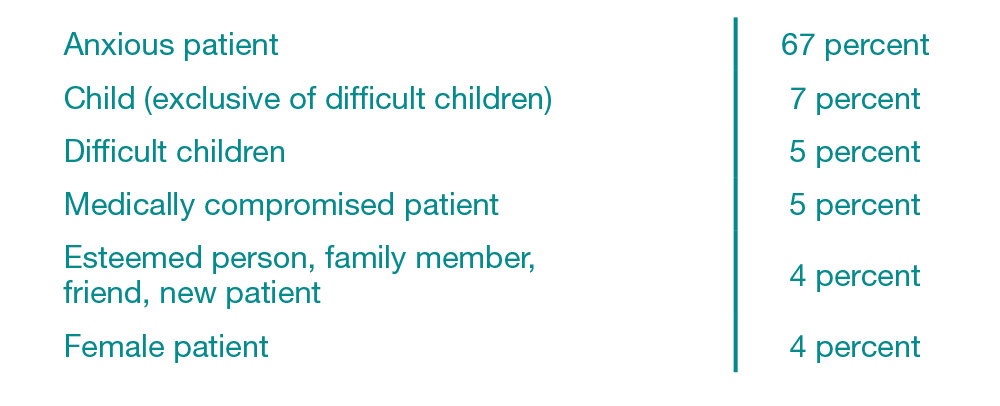

It is possible that as many as 67% of the entries in Table 1 are characteristics of an anxious person. Table 2 lists the responses that could broadly be defined as referring to an anxious person.

After the anxious patient (including difficult children), it is children who make dentists most anxious (7%) about giving injections. This may be due to a child’s more expressive reaction to pain and anxiety. Five percent of the answers indicated it is the medically compromised patient who creates the most anxiety for the dentist. The patient’s occupation, status, relationship and the female patient were mentioned in 4% of the entries as causing the dentist the most anxiety. An esteemed person, family member, friend or new patient may cause the dentist to fear failure or negative critical appraisal when he is about to perform a task (local anesthesia) that the patient can accurately judge. Interestingly, dentists indicated that women patients created the most anxiety four times as often as they indicated that men did. Although other factors may be prompting this skewed response, it is good to keep in mind that the study sample of alumni had five times as many men as women.

Table 3 lists the six most frequent responses by category.

Besides these responses of what patient makes the dentist most anxious about giving injections, 33 or 545 respondents, or 6%, indicated there was no particular type of patient that makes them anxious. In fact, one study9 concluded that the presence or absence of perceived patient anxiety does not appreciably affect dentist stress. This data supports findings8,9 that intrinsic factors that vary from individual to individual determine why dentists respond differently to the same stimulus.

There are several factors that must be examined when analyzing this study for limitations.

- The survey was of the alumni of one dental school.

- The 711 dentists, or 24%, who returned the survey and those 545 who answered the question on which this study is based are not a random sample and thus there may be sampling biases. Perhaps the most anxious dentists were most likely to respond.

- The groupings and categories were subjectively drawn and there is much room for rearranging the data.

- There can be conjecture over some of the entries being listed as displays of anxiety, especially in the section of Table 1 labeled “Indirect Expression of Anxiety.”

Table 2

Responses from Table 1 that might be characteristic of an anxious patient

Table 3

Type of patient who makes the dentist the most anxious about giving injections

Conclusion

There are many stressors in the practice of dentistry6: the strain of perfectionism and seeking ideal results, economic pressures, third-party constraints, interpersonal relations, the physical strain of work and patient compliance. Each practitioner has other aspects of dental practice that cause stress. The biggest concern for the patient is the potential pain and resultant anxiety associated with dental treatment. Based on a number of studies,6-11,13 the patient’s anxiety and pain create stress and distress to the dentist.

This paper is an analysis of the 676 responses to the short-answer question: “Is there one type of patient that seems to make you the most anxious about giving injections? If so, please describe this patient.”

This survey mailed to 3,000 alumni of University of the Pacific School of Dentistry and other studies documented in this paper indicate that the patient is not the only person in the operatory who may be feeling anxious about the patient’s injections. At least 67% of the 676 responses to the survey question indicated that it is the anxious patient who makes the dentists the most anxious. About 16% of the dentists are most anxious when having to inject a child.

Because almost every patient visit to the dentist is accompanied by a needle penetration or another invasive procedure on sensitive tissues, the patient’s anxiety and potential for pain have become synonymous with dentistry. There are many patient behaviors of anxiety, such as expressions, body language, speech content and tone, and physical actions that are communicated to the dentist. This information is transmitted to the practitioner through the two most frequently used sensory organs in interpersonal relations: the eyes and ears. The dentist’s thoughts and feelings are thus affected repeatedly by patient messages of, “You are emotionally or physically causing me pain and discomfort.” It is clear then why these daily, patient-by-patient experiences distress the dentist.

Although there was much subjectivity in the groupings of the data, it is apparent from dentists’ responses in this survey, and from other cognitive and physiologic studies, that it is the anxious patient who makes the dentist the most nervous about giving injections. To know this is to recognize one of the biggest enemies to peace and fulfillment in private practice. A multifactorial approach can then be planned to:

- Reduce the activities of the office personnel that create or intensify the patient’s anxiety.

- Help the patient reduce his endogenous activity.

- Use available resources to help the dentist and hygienist deal with stress and anxiety. Consider using a consultant, if the office personnel and patient’s well-being is disturbed.

References

Dr. James Dower is the director of the Local Anesthesia Course and an associate professor with the Department of Operative Dentistry at University of the Pacific School of Dentistry. Contact Dr. Dower at jdower@pacific.edu or 415-929-6538.

Dr. James Simon is chairperson and associate professor with the Department of Operative Dentistry at University of the Pacific School of Dentistry. Contact Dr. Simon at simon2@uthsc.edu.

Dr. Bruce Peltier is an associate professor of psychology with University of the Pacific. Contact Dr. Peltier at bpeltier@sbcglobal.net or 415-215-5868, or visit brucepeltier.com.

Dr. David Chambers is associate dean for Academic Affairs and professor of dental education with University of the Pacific School of Dentistry. Contact Dr. Chambers at dchamber@pacific.edu or 415-929-6438.

- ^ Mallinger MA, Brousseau KR, Cooper CL. Stress and success in dentistry. Some personality characteristics of successful dentists. J Occup Med. 1978 Aug;20(8):549-53.

- ^ Gift H. Occupational hazards and emotional stress as related to morbidity and mortality of dentists, a review and comment on published research. American Dental Association, Bureau of Economic Research and Statistics, Chicago, 1977.

- ^ British office of Population Census and Survey. Aust Dent J. 1993;38(5).

- ^ Dunlap JE, Stewart JD. Stress in the dental office. Dent Econ. 1981 Sep;71(9):50-2.

- ^ Dunlap JE, Stewart JD. Suggestions to alleviate dental stress. Dent Econ. 1982 Mar;72(3):58-60, 62, 64.

- ^ O’Shea RM, Corah NL, Ayer WA. Sources of dentists’ stress. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984 Jul;109(1):48-51.

- ^ Render J. Providers’ reaction to dental patients’ pain. Mil Med. 1985;150:160-4.

- ^ Borea G, Montebugnolich L, Braiato A. The effects of patient anxiety on the cardiovascular stress of dentists. Quintessence International. 1989;20(11):853-7.

- ^ Moore C, Liggett WR. The inferior alveolar block: effect on the dentist’s heart rate. General Dent. 1983;31:386-8.

- ^ Rosenberg M. The cardiovascular response of oral and maxillofacial surgeons during administration of local and general anesthesia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987 Apr;45(4):306-8.

- ^ Mazey K. Stress in the dental office. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1994 Feb;22(2):13-9.

- ^ Klepac RK, Hauge G, Dowing J. Treatment of an overactive gag reflex: two cases. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1982 Jun;13(2):141-4.

- ^ Rankin JA, Harris MB. Comparison of stress and coping in male and female dentists. J Dent Pract Adm. 1990 Oct-Dec;7(4):166-72.

Reprinted by permission of the California Dental Association. Dower JS Jr, Simon JF, Peltier B, Chambers D. Patients who make a dentist most anxious about giving injections. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1995 Sep;23(9):35-40.