Simplifying Laboratory Communication: The Dental Midline Position, Incisal Cant and Incisal Horizontal Plane

Introduction

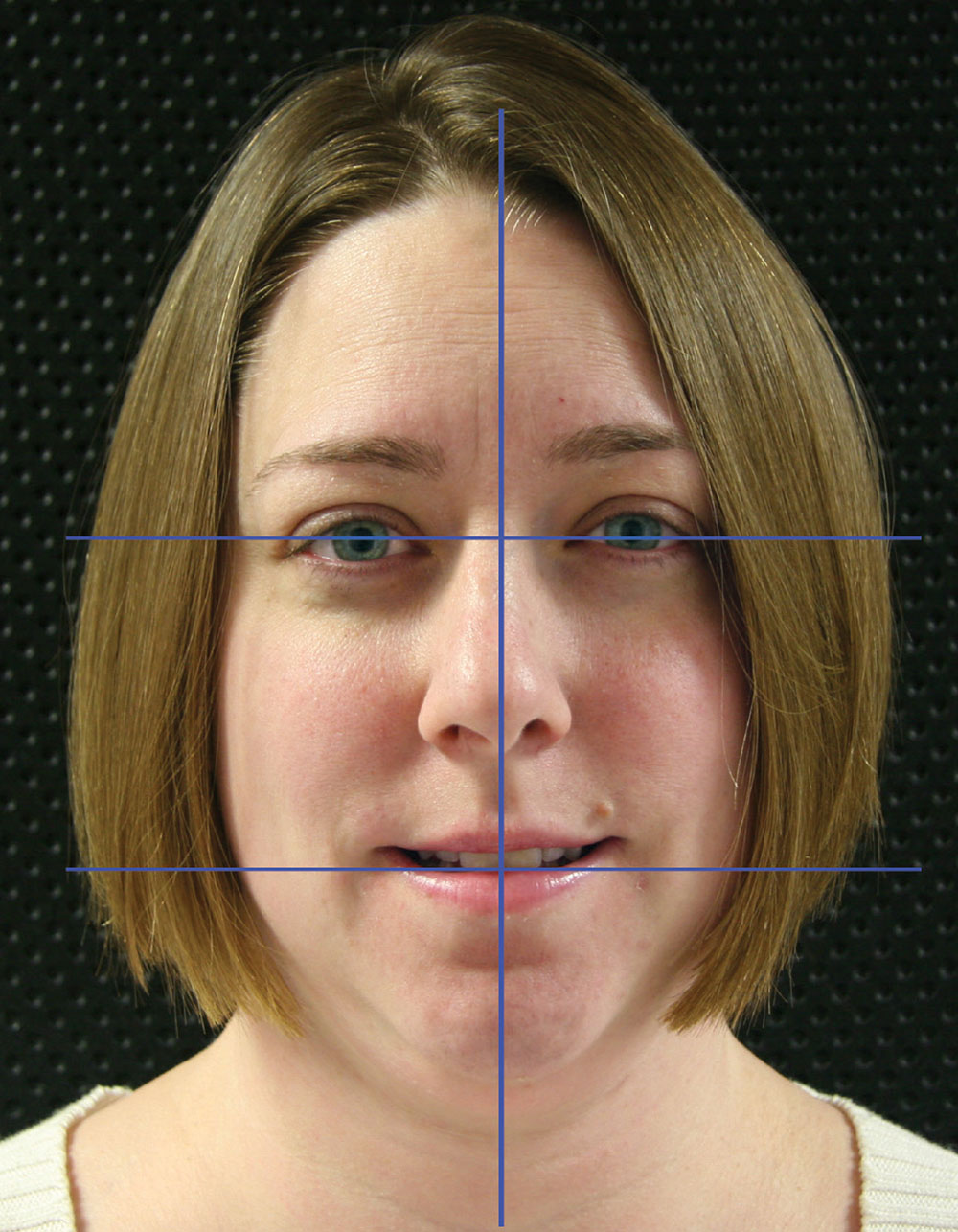

The primary objective of aesthetic dental treatment is to generate a natural, healthy appearance for an otherwise damaged dentition.1 The word “aesthetic” implies beauty, naturalness and a youthful appearance relative to one’s age, and aesthetic dentistry has been called the “art of the imperceptible” by McLaren and Rifkin.2 A pleasing dental appearance is the subjective appreciation of the shade, shape and arrangement of the teeth and their relationship to the gingiva, lips and facial features.3 Symmetry, the property of being symmetrical, with a correspondence in size, shape and relative position of parts on opposite sides of a dividing line or median plane or about a center or axis,4 plays a large part in the perception of dental aesthetics (Fig. 1).

In a study by Dunn, when evaluating photographs of male and female smiles, 24 out of the 25 demographic groups picked the same attractive female smile, which was characterized by natural teeth having a light shade, a high lip line, a large display of teeth and radiating symmetry.5 Multiple studies show that society places a great amount of importance on appearance, with attractive people having more success, higher paying and more prestigious jobs, better luck in obtaining dates, more favorable jury verdicts and more positive responses, even from infants.6 The ability of the dentist to communicate the location and orientation of the patient’s facial landmarks to the dental technician will dictate the success of the aesthetic outcome.

This article will look at the aesthetic parameters of dental midline position, incisal cant and incisal horizontal plane, and provide a simple methodology to relate these parameters to the dental technician when multiple anterior restorations are prepared. Of course, details of the smile arc,7 the curve formed by the incisal edges of the maxillary anterior teeth in relationship to the lower lip, need to be communicated to the laboratory technician. The maxillary incisal curve and the lower lip curve should be roughly parallel to one another and perpendicular to the vertical midline drawn between the maxillary central incisors (Fig. 2).8,9 For complicated cases, it is critical to give an accurate relationship of the casts in a sagittal or lateral axis when designing the curvature and angle of the smile line (bicuspids to molars),10 as the potential for misalignment of the casts increases with the number of restorations involved.11

The Dental Midline

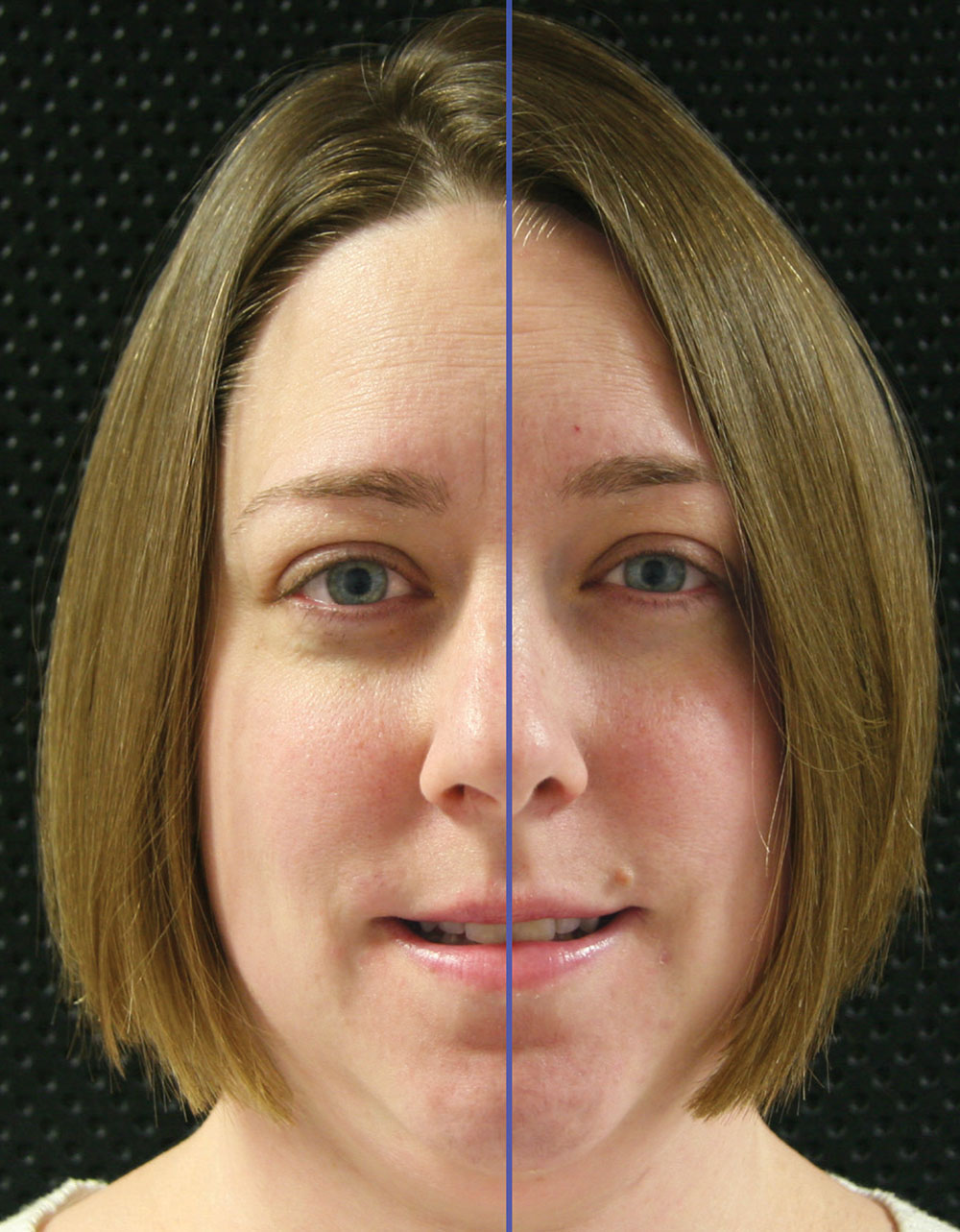

The median plane is a line passing longitudinally through the middle of the body from front to back, dividing it into the right and left halves.12 The facial midline is a critical reference position for determining multiple design criteria13 with the maxillary midline position relative to the facial midline stressed in orthodontic treatment planning,14 as it is an important functional component of occlusion.15 In a totally symmetrical face, the dental midline and the facial midline should coincide, but this is often not the case (Fig. 3). A study by Miller showed that the midline is situated in the exact middle of the mouth in approximately 70% of people, and the maxillary and mandibular midlines fail to coincide in almost three-fourths of the population (Figs. 4, 5).16 However, in a study looking at dental students, Soares found that the coincidence of facial midline with the arch midline occurred in only half of the students.17 Among orthodontic patients, the most common asymmetry trait is mandibular midline deviation from the facial midline.18 Thus, the mandibular midline cannot be used as a reference point by the dental technician in deciding where to put the maxillary midline (Fig. 6).

However, there is conflicting data as to how important the maxillary and/or mandibular midline position is to patients and their perception of aesthetics and the ability of dental professionals and laypeople to perceive dental midline shifts. It seems midline abnormalities are the least noticed.2

In a study by Dunn, when evaluating photographs of male and female smiles, 24 out of the 25 demographic groups picked the same attractive female smile, which was characterized by natural teeth having a light shade, a high lip line, a large display of teeth and radiating symmetry.

Johnston, when evaluating the dental attractiveness of facial photographs with orthodontists and laypeople, found that as the size of the dental to facial midline discrepancy increases, attractiveness ratings decrease. There was a 56% probability for a layperson to record a less favorable attractiveness when there was a 2 mm discrepancy between the dental and facial midline, while a discrepancy of 2 mm or more was noticed by 83% of orthodontists.19 A study by Chan quantifying a layperson’s ideal and maximum deviation of the midline found the smile became unattractive when the maxillary midline deviated 2.9 mm, or once the maxillary-mandibular midlines deviated 2.1 mm.20 Cardash, in his study of midlines, states that nearly half of the observers were unable to detect midline deviations of less than 2 mm; however, some detected midline deviations of less than 1 mm.21 Kockich claims that general dentists and laypeople are unable to detect even a 4 mm midline deviation.22 Irrespective of these studies, many authors state that when restoring multiple anterior teeth, the ideal choice is always to maximize the aesthetic result by placing the maxillary dental midline in harmony with the facial midline.1,23,24

Midline Cant or Oblique Midline

In the ideal face, the midline of the teeth should be centered in the face and be completely vertical.23 Even when the midlines of one or both arches are not centered, it is more important to ensure the anterior teeth are vertically oriented in the face and perpendicular to the incisal plane.25 Attractiveness scores and acceptability ratings decline consistently as axial midline angulation increases (Fig. 7).26 Studies have shown that midline deviations of up to 3 mm or 4 mm are not noticed by laypeople if the long axes of the teeth are parallel with the long axis of the face.22,26 Spear states that perhaps the most important relationship to evaluate is the mediolateral inclination of the maxillary incisors.27 If the incisors are inclined by 2 mm right or left, laypeople regard this as unaesthetic.26 Thus, this type of midline deviation (the oblique midline) is noticeable and should be corrected with interproximal preparation27

The Incisal Horizontal Plane

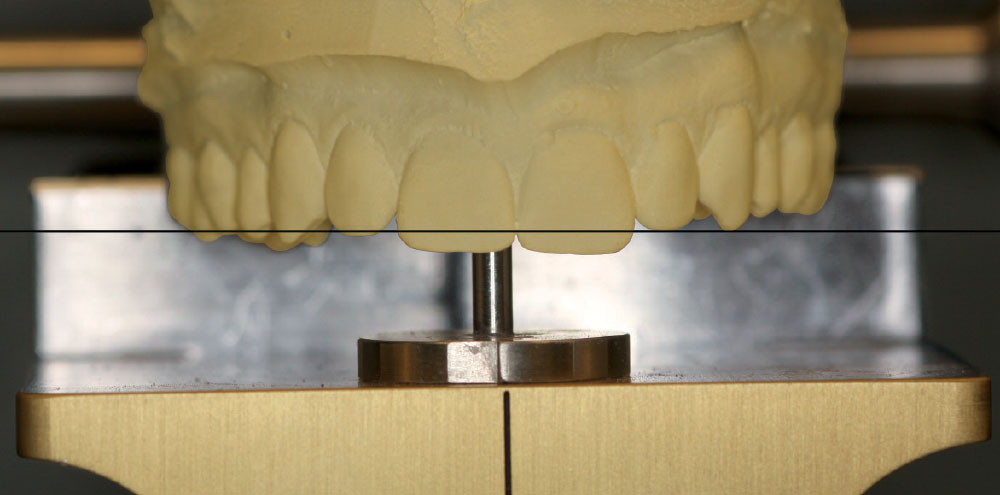

The interpupillary line is a reference plane used to determine the incisal horizontal plane, gingival plane and occlusal plane.1 An incisal plane cant of 1 mm is rated as significantly less aesthetic.22 Kockich found that an occlusal plane cant is a very displeasing smile characteristic to health professionals and laypeople.22 An incisal occlusal cant is a form of asymmetry that is apparent when a person smiles but is not perceived on intraoral images or study casts.28 Even when using a facebow transfer, the condylar determinants do not take into account the aesthetic orientation requirements because the anterior and posterior occlusal determinants are evaluated and transferred to the articulator from a functional standpoint with the assumption that the aesthetic orientation of the anterior teeth is correct.11 In addition, when referencing remaining unprepared teeth, their positions may not accurately represent the incisal horizontal plane of the incisors. Canine positions are generally asymmetric and are in different vertical positions as well as being angled differently (Figs. 8, 9).2,29 Thus, mounting casts referenced to the vertical position of the canines will result in the restorations having an incorrect incisal plane (Fig. 10).

Laboratory Communication

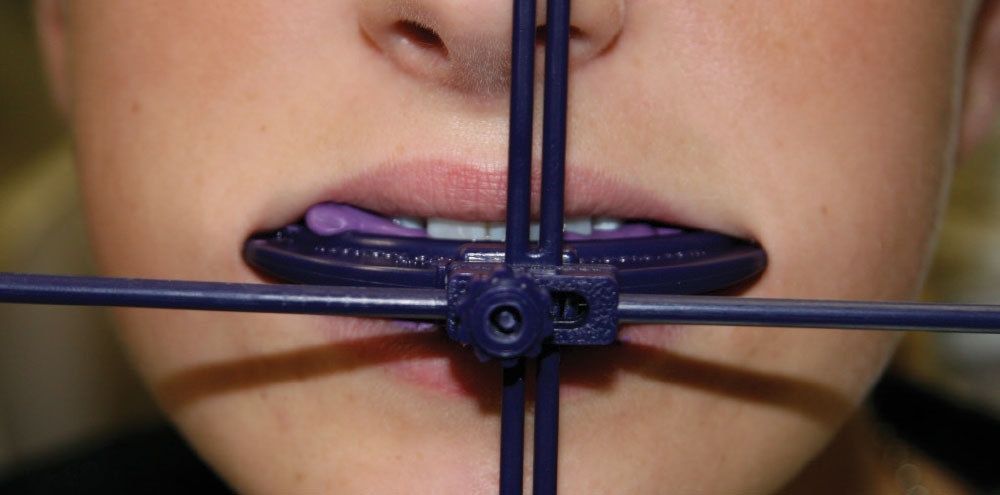

If the clinician is to transfer these important parameters of the maxillary dental midline, the lack of midline cant, and the incisal horizontal plane to the dental technician, which should all be referenced to the facial midline and interpupillary line, how is this reliably accomplished? In the past, classic stick bites, cotton swabs, pencils, plastic stir sticks and symmetry bites have been used to capture these dimensional relationships.10 The limitations of these systems are many. All have limitations due to the short working time of many bite registration materials, so the clinician is forced to work quickly to center and place these before the material sets. If the stick bite or symmetry bite is slightly off, the whole process needs to be repeated. With fixed symmetry bites, the vertical and horizontal are fixed at 90 degrees to each other, assuming the horizontal incisal plane matches exactly to the interpupillary line and no correction is indicated or anticipated. A stick bite to the horizontal assumes the patient can keep his or her head perfectly still and upright.

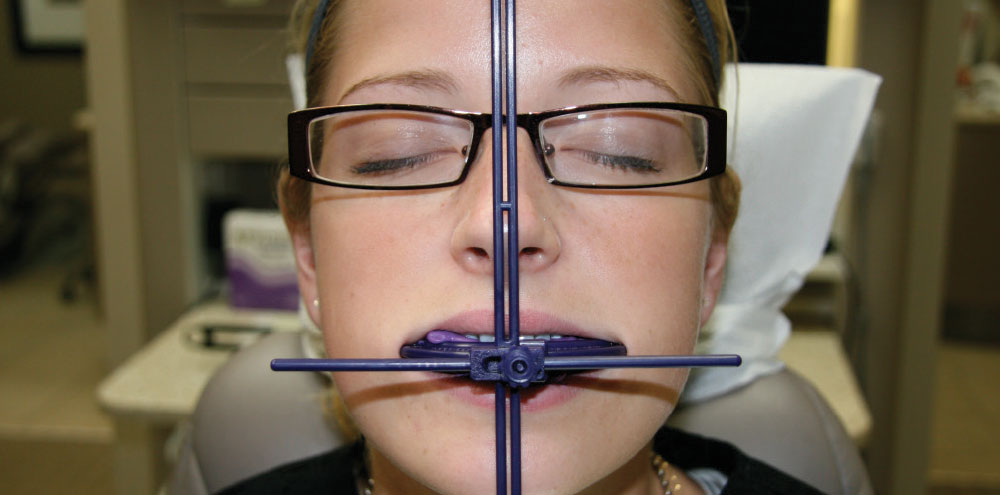

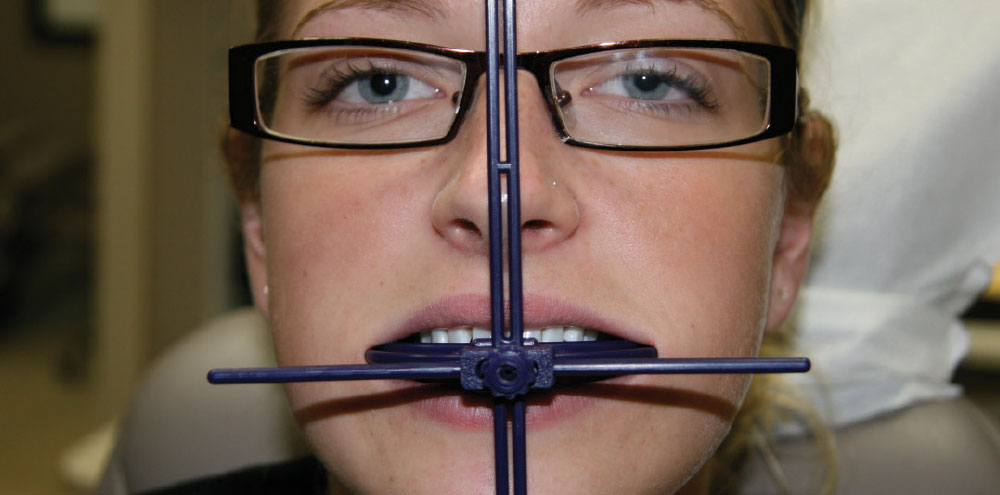

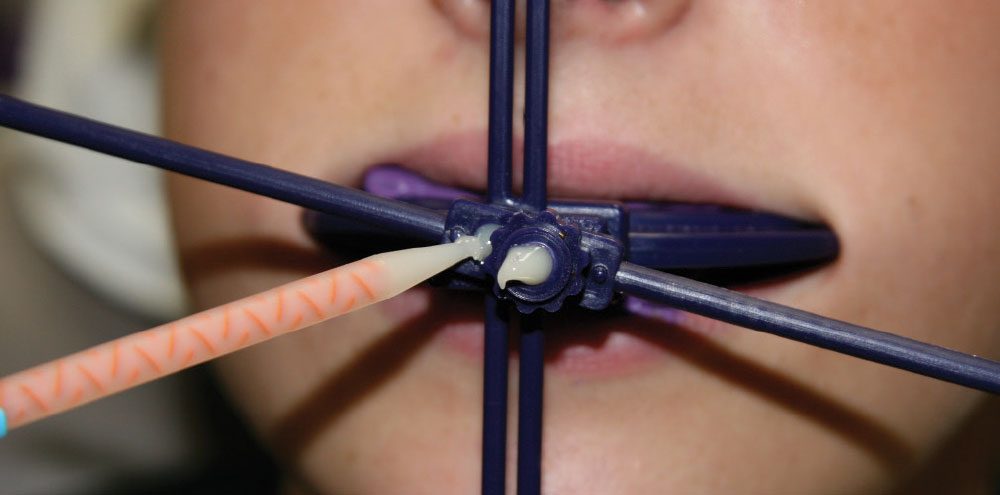

A simple solution to the transfer of the required data to the dental technician is the Onebite™ (Precision Dental Products; Draper, Utah) facial plane relator. There are a number of distinct advantages to the Onebite over other available systems. The bite fork portion is separate from the adjustable horizontal and vertical components, so that if the bite fork is placed slightly off center when placed into the bite material, the ability to move the components laterally eliminates the need for repeating the procedure. Figures 11–13 show the placement of the bite registration material Affinity™ Quick Bite (Clinician’s Choice; New Milford, Conn.) onto the anterior teeth, onto the bite fork and the intraoral placement of the bite fork. After the vertical and horizontal components were placed firmly into the bite fork slot, it can be seen (Fig. 14) that the bite fork was placed slightly off laterally to the patients left side. The bite fork placement does not have to be redone; Figure 15 shows the horizontal adjustment is easy to accomplish by loosening the screw, sliding the component laterally until centered to the patient facial midline, and then securely tightening the locking screw. Another benefit of Onebite is that the vertical and horizontal component can be left in a locked 90-degree relationship to each other if the patient demonstrates symmetry of the midline, horizontal and interpupillary line, or the components can be unlocked by rotating the horizontal bar so the locking pins are facing the clinician, if there is a discrepancy with the interpupillary line.

Figure 16 shows the patient’s right side horizontal portion of the Onebite is slightly lower than the interpupillary line. This can easily be adjusted by unlocking the components, rotating the horizontal bar until it is in harmony with the interpupillary line, securely tightening the locking screw and then fixing the components together by injecting temporary C&B material into the lateral slot and screw. For illustrative purposes, the rotation has been exaggerated in Figure 17 to show the wide range of adjustments that are easily managed by the Onebite. The components are then taken apart by placing lateral force on the locking screw, which facilitates transport to the laboratory. Another advantage of the Onebite is that in the laboratory, the vertical component can be reduced in length at the plastic cross supports to fit easily onto a semi-adjustable articulator.

A study by Chan quantifying a layperson’s ideal and maximum deviation of the midline found the smile became unattractive when the maxillary midline deviated 2.9 mm, or once the maxillary-mandibular midlines deviated 2.1 mm.

Conclusion

The rationale for the need of accurate communication by the dental clinician to the laboratory technician of the dental midline, incisal midline cant and incisal horizontal plane have been discussed. A simple technique that facilitates this communication has been presented and should minimize the need for expensive remakes for aesthetically driven restorations.

Dr. Len Boksman is adjunct clinical professor at the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry and maintains a private practice in London, Ontario, Canada. He is also a paid part-time consultant to Clinical Research Dental Inc. and Clinician’s Choice. Contact him at lboksman@clinicalresearchdental.com or 519-641-3066, ext. 292. *Reprinted with permission of Oral Health Journal, ©2010 Oral Health Journal. *

References

- ^ Rifkin R. Facial analysis: a comprehensive approach to treatment planning in aesthetic dentistry. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 2000 Nov-Dec;12(9):865-71.

- ^ McLaren EA, Rifkin R. Macroesthetics: facial and dentofacial analysis. J Calif Dental Assoc. 2002 Nov;30(11):839-46.

- ^ Nohl FS, Steele JG, Wassell RW. Crowns and other extra-coronal restorations: aesthetic control. Br Dent J. 2002 Apr 27;192(8):443, 445-50.

- ^ Bryan M, Calhoun K. All about chin augmentation facial proportions and analysis. Dept of Otolaryngology, UTMB, Grand rounds, Chin and Malar Implants Sept 6, 1995. Available at: http://www.chinaugmentation.com/facial_formula.htm.

- ^ Dunn WJ, Murchison DF, Broome JC. Esthetics: Patients’ perceptions of dental attractiveness. J Prosthodont. 1996 Sep;5(3):166-71.

- ^ Patnaik VVG, Singla RK, Bala S. Anatomy of a beautiful face & smile. J Anat Soc India. 2003;52(1):74-80.

- ^ Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile analysis and design in the digital era. J Clin Orthod. 2002 Apr;36(4):221-36.

- ^ Rufenacht CR. Principles of esthetic setup. In: Rufenacht CR, editor. Principles of esthetic integration. Carol Stream (IL): Quintessence Publishing; 2000.

- ^ Sarver DM. The importance of incisor positioning in the esthetic smile: the smile arc. Am Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001 Aug;120(2):98-111.

- ^ Chan CA. Architecting the occlusal plane. Las Vegas Institute for Advanced Dental Studies.

- ^ Chiche GJ, Aoshima H. Functional versus aesthetic articulation of maxillary anterior restorations. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1997 Apr;9(3):335-42.

- ^ http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Frankfort+horizontal+plane

- ^ Morley J, Eubank J. Macroesthetic elements of smile design. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001 Jan;132(1):39-45.

- ^ Beyer JW, Lindauer SJ. Evaluation of dental midline position. Semin Orthod. 1998 Sep;4(3):146-52.

- ^ Thomas JL, Hayes C, Zawaideh S. The effect of axial midline angulation on dental esthetics. Angle Orthod. 2003 Aug;73(4):359-64.

- ^ Miller EL, Bodden WR Jr, Jamison HC. A study of the relationship of the dental midline to the facial median line. J Prosthet Dent. 1979 Jun;41(6):657-60.

- ^ Soares GP, Valentino TA, Lima DANL, Paulillo LAMS, Silva FAP, Lovadino JR. Esthetic analysis of the smile. Braz J Oral Sci. 2007 Apr-Jun;6(21):1313-9.

- ^ Sheats RD, McGorray SE, Musmar Q, Wheeler TT, King GJ. Prevalence of orthodontic asymmetries. Semin Orthod. 1998 Sept;4(3):138-45.

- ^ Johnston CD, Burden DJ, Stevenson MR. The influence of dental to facial midline discrepancies on dental attractiveness ratings. Eur J Orthod. 1999 Oct;21(5):517-22.

- ^ Chan RW, Ker AJ, Fields HW, Beck FM, Rosenthiel SF, Johnston W. 0366 Esthetics and smile characteristics from the patient’s perspective, Part II. http://iadr.confex.com/iadr/2008Dallas/techprogram/abstract_100215.htm.

- ^ Cardash HS, Ormanier Z, Laufer BZ. Observable deviation of the facial and anterior tooth midlines. J Prosthet Dent. 2003 Mar;89(3):282-5.

- ^ Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak A, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11(6):311-24.

- ^ Paul SJ. Smile analysis and face-bow transfer: enhancing aesthetic restorative treatment. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001 Apr;13(3):217-22.

- ^ Tipton PA. Aesthetic tooth alignment using etched porcelain restorations. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001 Sep;13(7):551-5.

- ^ Reikie DF. Orthodontically assisted restorative dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001 Oct;67(9):516-20.

- ^ Spear FM, Kokich VG, Mathews DP. Interdisciplinary management of anterior dental esthetics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006 Feb;137(2):160-9.

- ^ Javaheri D. Considerations for planning esthetic treatment with veneers involving no or minimal preparation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007 Mar;138(3):331-7.

- ^ Sabri R. The eight components of a balanced smile. J Clin Orthod. 2005 Mar;39(3):155-67.

- ^ Chiche G, Pinault A. Esthetics of anterior fixed restorations. Carol Stream (IL): Quintessence Publishing; 1988.