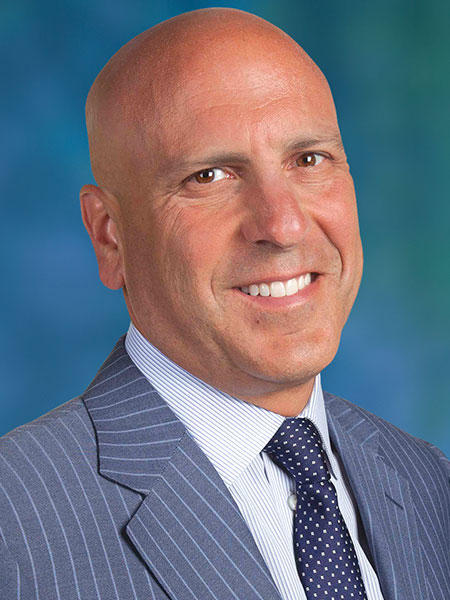

One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: Interview of David Harris

David Harris is a licensed private investigator and the CEO of Prosperident, a company that specializes in the investigation of frauds and embezzlements committed against dentists. I first heard about David when I came across his seminar “How to Steal from a Dentist” listed in the program for a dental meeting where I was lecturing. The title of his lecture captured my fascination, especially when I saw that it was a course designed to help dentists detect and protect against dental-practice embezzlement. I wasn’t able to attend his lecture during the dental meeting, so I thought the next best thing would be to ask him to share his expertise on the subject in Chairside® magazine.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: For those of our readers who haven’t had the opportunity to see your lecture on dental-practice fraud yet, can you tell me a little bit about your background and how you got involved in dental embezzlement investigation?

David Harris: I’ve been investigating dental embezzlement for about 22 years. Before that I did various things. I was in the Army for a while; I did investigation for a bank. After retiring from working for the bank, I was sitting at home not doing a whole lot when I got a call from a friend of mine who happened to be a dentist. He said, “I think my front-desk person is stealing from me, and you’re the only guy who I can think of to turn to on this.” So I went to his office that night, we found the fraudulent employee and we got rid of her. I went back to watching TV and really didn’t give it another thought.

It was a coincidence when about three weeks later I went to my own dentist for a hygiene appointment and saw through the glass of the office door the same person who we had terminated from the other office three weeks earlier! So I ran away quickly hoping that she didn’t see me, went to the nearest pay phone — this story pre-dates me having a cell phone in my pocket — and phoned the dentist. I got put through to him on some pretext and I said, “I’m not coming in for my appointment today, but when I tell you why you’ll probably forgive me.” I told him about the time bomb he had sitting at the front desk, and he asked me what he should do next. Halfway through my second sentence he hired me. Things have changed a lot since then in a whole bunch of ways. I was doing this on my own then, and now I have a decent-sized company that helps me with investigations, but the basics haven’t changed.

MD: That’s an amazing story. In terms of dentistry, I guess it’s not that surprising in the sense that in most of our communities, and even nationally, dentistry is a very tight-knit group where you know and see a lot of the same people. Even in corporate dentistry, with the dental product manufacturers, you’ll see somebody leave one company and then a new CEO gets hired at another company. It seems like the same people are shifting slots and moving around. So I guess it’s not shocking that somebody who gets fired from one dental office job turns up at another dental office.

DH: It’s what they know. In the case of this particular woman, it was lucrative because she was getting paid her official salary and then her, shall we say, “unofficial” salary.

MD: It’s not like when she got fired from the first practice that there was a scarlet letter put on her forehead to identify her as an embezzler on any interview she might go on after that, right?

DH: Thieves are pretty good at doctoring their résumés enough to hide their backgrounds. One of the most common lines is simply telling the new employer that they’re still working at the previous place and saying, “My old employer doesn’t know I’m leaving, so please don’t call him.”

MD: That’s an interesting line. I get the feeling that we’re going to hear about some slightly ingenious — albeit evil — things like that today. I guess these people have figured out how best to cover their tracks.

DH: Thieves are pretty clever. One of the most interesting parts of my job is witnessing the sheer creativity that some of these folks show. I will now have to disappoint your readers a little bit because our policy in an uncontrolled forum like this one is not to talk specifics. My recurrent nightmare is to turn thieves into better thieves. We do talk about specifics in closed seminars, but in this interview, I feel a little bit constrained. Some of the stuff we see is almost spectacular in its ingenuity. You can’t help thinking about what these folks could accomplish if they put their minds to honest labor.

MD: I guess what they’re doing on a small scale is what happens in big Wall Street firms when there is embezzlement. I don’t know if you have come across any studies or surveys on this, but what percent of dentists would you say will have embezzlement be an issue in their office at some point in their career?

DH: In the published statistics, there are two or three surveys saying that somewhere between 50% and 60% of dentists will be victims. But there is a confounding factor to this because there is a fair amount of embezzlement that never gets detected by anybody and therefore won’t be in the statistics. So the true number is probably higher, but I think it’s safe to tell your audience that at least three in five dentists will be victims at some point in their careers.

MD: Wow, that seems like a pretty high number. I wonder how much of that is from repeat offenders like the person you referenced in your first story where she goes from one office to another. Is that a common occurrence?

DH: It definitely happens. We call them serial embezzlers. There was one woman who was working in the Toronto, Canada, area. Over a period of four years, she worked in 13 different practices and stole from all of them. She was really good at getting hired, but as a thief — despite a fair amount of practice — she wasn’t all that skilled. So she would get caught fairly quickly and get terminated, then move to the next office.

MD: If these so-called serial embezzlers can come up with creative schemes that continue to impress you, I would guess that they have decent verbal skills when it comes to lying. So couldn’t they show up at an office and seem to be a dream employee?

The serial embezzlers are very much take-charge people. They cater to what I sometimes call the “wet-fingered fantasy” some dentists have. A fantasy where they get into their office every morning, do high-quality dentistry on a relatively small number of patients and then go home, without having to get dragged into the messiness of managing their practice.

DH: Absolutely. The serial embezzlers are very much take-charge people. They cater to what I sometimes call the “wet-fingered fantasy” some dentists have. A fantasy where they get into their office every morning, do high-quality dentistry on a relatively small number of patients and then go home, without having to get dragged into the messiness of managing their practice. The serial embezzlers cater to that. They know the computer systems really well; they’re organized and efficient. They look like they are working hard. It’s what every dentist wants. So it’s easy for them to get hired because when they’re in the door, they cater to this idea. They’re the people who will run personal errands for you on their lunch hours.

MD: To back up the impression that they are somebody who would take a bullet for you, so how could they ever embezzle?

DH: That’s right. Now, having said all that, the vast majority of embezzlement is not carried on by the serial embezzlers. It’s done by long-time employees. The big stuff that we investigate is usually from employees who have been in your office for 3, 5 or 12 years. Generally speaking, we think that these people had no plan to embezzle from you when they were hired. But then something happened to them that put their backs to the wall financially, and they decided that instead of going downtown and stealing people’s wallets, just sitting at the same desk where they work every day and handling the paperwork a little differently was a better answer.

MD: Wow, so it’s often somebody who started off as a trusted employee and probably has a well-deserved good reputation?

DH: Clean employment record, no blemishes on it at all. One morning they just woke up and said, “Today is the day I’m going to steal from my employer.”

MD: Yeah, or something happens. Maybe they lose their house, a spouse loses a job, or they get divorced. There might be a situation that makes them desperate enough to steal from a person they might have previously held a lot of affection and trust for.

DH: What I’ll suggest is that there are different definitions of desperation. There are some real hardship cases like the examples you mentioned; you know, somebody who is three months behind on their mortgage payment and is about to lose their house. We also find people who steal to get things that you and I probably wouldn’t consider necessities. We’re wrapping up an investigation now where the woman who was stealing was spending $800 a month on a personal trainer, and she also belonged to something called the Shoe of the Month Club. I wouldn’t consider her to be desperate. But of course what I think doesn’t matter; it’s her perception that governs her behavior.

MD: Exactly. Do you think dentists are more prone to this type of embezzlement than other small businesses?

DH: Probably. There is one differentiating characteristic between the way dentistry operates compared to, say, a plumbing business. The differentiation has nothing to do with the amount of business knowledge that each owner has, or the amount of attention that each spends on business versus the other things in their trade. What sets dentistry apart is that a lot of it is paid for by third parties. So we have this unstable situation where patients, for the most part, really don’t understand a whole lot about what just happened in their mouth, and somebody else is paying for it anyway. So the amount of attention that patients pay when leaving your office is minimal. If there is an extra charge in there or something that shouldn’t be, very few patients are going to notice it and object.

MD: Especially if it’s an extra charge that is billed to the insurance company, right?

DH: That’s right. So somebody gets extra soft tissue work done today, and it’s billed to their insurance company. Most of the time the patient won’t notice.

MD: My original perception was that most of the embezzlement taking place in the dental office was from the cash patients as opposed to the insurance patients. The latter seems like a more difficult embezzlement because of the paper trail that is left with the insurance company. But you’re saying that it is just as likely to happen with the insurance people as the cash people?

DH: Yes, it is. In fact, most embezzlers do both simultaneously. Dentists look at an insurance claim as a clinical document. To me, it’s a check requisition.

MD: That’s a good point. Without giving too much away, are you saying that if a crown is done on a patient and the front-office person adds an extra buildup that wasn’t done, for example, that the employee is able to skim that amount off the top when the whole thing gets deposited?

DH: That’s exactly right.

MD: Interesting. Have you found that the vast majority of employees who embezzle are front-office staff? This seems like something that would be much more difficult for a hygienist or a chairside assistant to pull off.

DH: I don’t think it’s more difficult; they just have to be a little bit more creative. We all know what has happened in the past three or four years to the price of gold. A lot of dentists I know have what they call a “gold jar” in the back of their lab. This is where they put the crowns they pull out of people’s mouths for various reasons. A lot of dentists jokingly refer to this as their retirement. Well, I’ve had a number of them say to me that since the price of gold has doubled, the gold jars don’t seem to fill up as quickly as they used to.

MD: Wow, that’s an interesting one, but it seems a little tougher to prove. Are you able to catch people in those kinds of situations? Or is that just something that gives dentists a feeling that something funny may be going on in their offices?

DH: You can catch them if you install cameras. And there are indicator powders that you can put in places that will turn people’s fingers purple if they touch it. If you want to catch them, you can.

MD: I was noticing the other day that cameras seem to be everywhere. Almost everything we do is being recorded. You see cameras out on the street, you see them inside stores — you even see them on the air train that takes you from the airport terminal to the rental car lot. Do you suggest that dentists start putting cameras in their offices as well?

DH: I’m trying to make up my mind about that, the usefulness of cameras with respect to embezzlement. In terms of catching most embezzlement, I think cameras are useless. Because you’d have to be the dumbest of thieves to visibly steal in front of a camera that you know is there. Let’s say you have four cameras in your office and your office is open 30 hours a week, your cameras are capturing 120 hours of video a week. The practical issue is: When are you going to watch the footage? On the other hand, there have been dentists who have been accused of groping a sedated patient and things like that, and to me a camera would be a marvelous way for the dentist to defend against that kind of thing. So I can see the necessity of cameras in the clinical area perhaps more than in the administrative areas of the practice. But even with that, there are a lot of questions. Placement of the camera is critical to avoid ever being accused of placing it in a bad place, say in an area where you could look up women’s dresses or something like that.

MD: With most of the embezzlement that goes on, do you get the feeling that it happens during working hours while everyone is there? Or does it happen during off-hours?

DH: A lot of it happens off-hours. One of the things we frequently see with embezzlers is that they come and go at weird times. It does happen during office hours, but a lot of embezzlers want to be alone when they’re doing their stuff.

MD: That also seems to tie in with what you said about the long-term employees. I would guess that if there are a few employees who have keys to the dental office that they are probably the longer-term employees versus the new employees.

DH: Sure, and it will also be the ones who appear to be the hardest working. They’re the ones who are going to go to the dentist and say, “There’s some stuff I want to clean up on Saturdays, can I please have a key?” And then the dentist is going to think: “This is great, I’ve got a staff member who is super dedicated. I should give them an outlet for that.”

MD: When you listen to practice management speakers, almost all of them emphasize that one of the key traits to having a very successful dental office is your ability to attract and retain long-term staff members and not have a lot of turnover. This really is the first time I’ve considered that long-term employees might be the ones who embezzle more often than the new employee who is the serial embezzler. Do you find that dentists are conflicted about this notion?

DH: We can’t lose sight of the fact that the vast majority of dental office staff members are honest people who got into dentistry out of a genuine desire to help people. The bad apples are relatively few in number, but over the course of a 30-year dental career, you’ll go through a lot of employees, so the chances of getting one of those bad apples at some point is high. That doesn’t mean that the vast majority of dental staff members are dishonest. I agree completely with the practice management consultants when they say long-term employees are part of your success. They don’t steal because they’ve been there for a long time. If they act dishonestly, it’s their longevity that enables them to get away with it. Because they know the dentist, his habits, and what the dentist looks at and what he doesn’t, they can craft their fraud in a way that bypasses scrutiny. For example, if you’re a dentist who checks your day sheet every day — I think every dentist should do that — then someone who is going to embezzle from you knows that. So they’re not going to do something that leaves a mess on your day sheet. They’ll have to find a different way to steal.

MD: I know we have a lot of staff members who read our magazine, so I’m glad you brought that up. Maybe a better way to state the practice management message is to say that a lot of a dental practice’s success comes from the dentist’s ability to find and retain honest, long-term employees. The long-term, dishonest employee is a counterintuitive thought, and I think most dentists would be flabbergasted to find out that a long-term employee is the one embezzling from them. But I think it’s a good point to make just because of the fact that those employees would probably be the last people a dentist would suspect in a situation like that.

DH: A lot of dentists go through a period of disbelief. They’ll see some signs that somebody is stealing from them, and then they think about their employees and they’ll sort of rule everybody out — even those who they think have an opportunity to embezzle. They’ll convince themselves that the theft isn’t happening, and then they’ll go back to work. At some point the noise gets a little bit louder and something happens that they just can’t categorize as an innocent mistake anymore, and then they realize they have a problem. A lot of times there is a denial period that dentists go through when they have long-term employees because they have a lot of trust in those employees, whether it’s misplaced or not.

MD: Have you come across instances of a family member working at the office and being responsible for the embezzlement?

DH: Yes, we have. One scenario is when you have one spouse who is the dentist and one spouse who is the office manager. The office manager has decided to get divorced from the dentist, but hasn’t told the dentist that yet. So they need to build up a war chest in order to pay their attorney and find a place to live because their only source of income is employment income from their spouse, which is presumably going to be cut off when they drop the divorce bomb. The spouse knows they will need money under the mattress and that’s how they get it.

MD: I was thinking more about kids coming to work in the office, or maybe an in-law. But that’s a great example that never occurred to me. Do you have a list of potential warning signs that dentists might see happening in their practice that could warrant an investigation?

DH: We do. This is maybe where I have a slightly different view than a lot of people who write and speak about embezzlement. Many of them try to turn dentists into what I would call untrained, ill-equipped auditors in their own practices. These advisors give the dentists lists of things to check for and to look at in order to stop embezzlement, or to find out if it’s happening. My approach is a little bit different. What I tell dentists is that there might be a thousand different ways to embezzle from their practice, but regardless of which of those thousand the thief is using, the way these thieves behave is very predictable. We already mentioned the people who are in the office alone at unusual times. You also might consider that employees who are reluctant to take vacations might have their finger in the till. So we have what we call the “Embezzlement Risk Assessment Questionnaire,” which is a scored questionnaire. If you score at a certain level, it tells you that you either have very little risk or, conceivably, that you are at high risk of embezzlement going on in your office.

MD: So are you saying that one type of employee who might be suspicious is someone who gets two weeks’ paid vacation from the dentist but never uses it and cashes it out? Or maybe it’s the person who wants to stay in the office even when everybody else goes on vacation?

DH: Yes, that’s a symptom. Whether they get cash for their vacation or not is irrelevant. To me, the real issue is that they do not want the office open when they are not there.

MD: I see, so they want to be able to cover their trail at any moment if something irregular is discovered. They probably worry that if they are gone for a week and somebody starts digging through the computer that any irregularities could be noticed.

DH: What uncovers a lot of fraud is patients asking questions about things. A very common scenario is when a patient says, “I was in two weeks ago and I paid by cash, but I just got my statement and it showed that I paid by check.” If that call comes to the thief, they can squelch it by saying: “Yes, I know. We just upgraded our computer system and there are a couple of bugs. The software vendor is working on it. We’re very sorry it happened.” It doesn’t matter whether there is one of those calls a day or a hundred, the thief can make them go away. On the other hand, if the thief is not in the office and there is someone else getting these calls, sooner or later that person is going to say to the doctor that something funny is going on. And then it unfolds. It’s about control of information in the practice, and the thief can only exert that control by being there.

MD: That makes sense. They’d probably even insist on taking all phone calls, right?

DH: That’s right. They’re often the ones who almost lunge for the phone when it rings. For a dentist who doesn’t suspect fraud, this looks like a very motivated, committed employee.

MD: Might this employee work on having the best phone skills in the office, so it only makes sense to have them answer all calls?

DH: Definitely.

MD: From the different cases you’ve seen over the years, what would you say is the range or average of how much money is usually taken?

We see everything from stealing toilet paper at the office to frauds that exceed a million dollars. The average we see these days is probably a little over $100,000. I think last time we did the calculation it came out to about $105,000.

DH: We see everything from stealing toilet paper at the office to frauds that exceed a million dollars. The average we see these days is probably a little over $100,000. I think last time we did the calculation it came out to about $105,000.

MD: Have you actually caught somebody who was just stealing toilet paper?

DH: It’s not one that we normally chase. But it certainly happens, and we do have dentists complaining to us about it. Sometimes it’s the tip of a bigger iceberg. But, yes, we do have lots of dentists who complain about things going missing when the staff members are probably the only people with the opportunity to steal. Another thing is, if you look on eBay, you’ll see all kinds of dental gear for sale.

MD: Interesting. To my knowledge, I have never been embezzled from. But in preparing for this interview, I was trying to think like the criminal mind, and ask myself what I would do if I had the opportunity. A chairside assistant could maybe sell bleaching kits on eBay, the kind that don’t need custom trays, like the pre-made ones from Ultradent. Those could be sold on eBay directly to patients for a markup. Is that the kind of thing you’re talking about, or do you mean actual equipment?

DH: Both. If a compressor is for sale on eBay, I highly doubt the dental assistant snuck it out of the office while nobody was watching. But you’ll see hand instruments and all kinds of consumables that are for sale online at a lower price than you can buy them from a supplier. Theoretically, I guess some of this stuff is gray market that somebody bought in some other country and imported. But I think the vast majority of it just kind of “fell off the truck” in one way or another.

MD: Wow, and that’s not really something that anyone polices, or could even. It seems like a difficult thing to try to get a handle on.

DH: I hate to say it, but I think most of the purchasers of this stuff aren’t end consumers buying bleach kits, but other dentists saying, “Wow, this stuff is really cheap on eBay.”

You’ll see hand instruments and all kinds of consumable that are for sale online at a lower price than you can buy them from a supplier. Theoretically, I guess some of this stuff is gray market that somebody bought in some other country and imported. But I think the vast majority of it just kind of fell off the truck in one way or another.

MD: In a dental office where the dentist doesn’t pay a lot of attention to what arrives in the boxes from Patterson Dental or Henry Schein, you might have somebody ordering things at full price and then putting them on eBay. Three days later when it disappears, no one misses it because the dentist didn’t really need it or even order it in the first place, right?

DH: Yes. Unless it’s enough to distort the ratio of consumables to productivity, which would have to be a whole lot of stuff going out the back door, nobody is ever going to notice.

MD: I’ve heard stories about dental assistants, for example, coming into the office on a Saturday and making bleaching trays for people and charging for it. Obviously it’s illegal, but is that considered embezzlement as well?

DH: I’m not sure it meets the formal definition of embezzlement, but it’s some kind of stealing, yes. What it really amounts to is practicing unlicensed dentistry. I saw something the other day about a dental assistant who would bring her friends in on Saturdays and do fillings on them.

MD: The very first story you told was about a woman who was fired from one practice for embezzling, who you then ran into at another practice. Then you told me about the woman in Toronto who stole from 13 practices. It seems like at some point they would be prosecuted. Is it up to the dentist to decide whether they want to prosecute these employees?

DH: Prosecution is the responsibility of the government, not the individual dentist. So when people say, “I’d like to press charges,” or “I’d like to not press charges,” they’re assuming a privilege that they really don’t have. It is the government that carries that responsibility and the financial and evidentiary burden that goes with it. Having said that, what a dentist can do is either communicate their interest in having somebody charged, or communicate that they really don’t want a person charged. Most of the time law enforcement and prosecuting agencies will give some weight to that. Also, if somebody hires us to investigate and we gather a fair amount of evidence, they can instruct us whether to share it with law enforcement. If we don’t share that evidence with law enforcement, in most cases they will have no interest in prosecuting because they don’t have the realistic means of gathering the same information themselves.

MD: Have you seen any cases where it was not a full-time employee doing the embezzlement, but instead the dentist’s accountant or somebody who only comes in once a month, an auxiliary position like that?

DH: The only cases where we’ve seen an appreciable amount of theft is with some kind of bookkeeper or accountant; somebody who has some level of control over the banking function, such as writing checks. A part-time bookkeeper is the only bookkeeper there, so even if that person only comes in three days a month, there is nobody else doing the job when they’re not there. So they can probably succeed there on a part-time basis. With somebody like a part-time receptionist, however, we really see very little stealing. Somebody who mans the front desk on Fridays is going to have a tough time getting away with much.

MD: Might another warning sign be an employee who insists on doing all the insurance claims herself?

DH: Yes, refusal to delegate is one thing. Another sort of related symptom is refusal to cross-train. A lot of these people come off as perfectionists. They tell the dentists that if somebody else does it and messes it up, then they have to fix it. In the meantime, your cash flow suffers because all these claims have been sent to the wrong place. The employee convinces the dentist that he or she is a perfectionist, which generally we consider a positive with employees rather than a negative characteristic. So the dentist tends to be receptive to this argument and the thief gets away with it.

MD: It has to be even more confounding for a dentist to have an employee with all these fantastic traits that they wish all their employees had, and then to find a knife in their back with that employee’s fingerprints on it. Are you aware of some dentists who have been embezzled from multiple times?

DH: Definitely. In fact, once you’ve been embezzled from once, the probability of you being a repeat victim is actually higher than the general dental population. About two-thirds of recorded embezzlement is from people who have already been a victim. The probability goes up from 50% to 60% to something closer to 70%.

MD: How do you explain that?

DH: I think the short answer is that some dentists are probably easier to steal from than others. What makes them easier to steal from could be anything from personality to how they run their office to who else is working in the office. There could be a lot of factors. Again, the chances of hiring a bad apple in your career are pretty good. The chances of hiring two are also pretty good.

MD: Once somebody in the office is caught and nothing about the way the office is run changes, do you think it gives other people in the office the idea to do the same thing?

DH: I don’t think that is what happens. I think five years goes by, somebody else gets hired and that person steals. The not checking the day sheet thing is a little bit of a red herring. But if I’m a nice, easygoing dentist, for example, the staff might get the idea that they can steal from me without me really doing anything, because I’m just way too nice. So I think if one staff member can form that opinion about a dentist, so can two or three more.

MD: Let’s say I think I’m having an issue in my office and I give you a call. Can you tell me a little bit about what the process is like after that?

DH: Sure. The first thing we do is have somebody reasonably senior at my company interview the dentist to see what the dentist is seeing, and just try to validate that there could be a problem. Sometimes we get dentists who don’t really think there is a problem, but they have an employee who did one thing to them once three years prior that they think could be symptomatic of stealing. We usually tell that doctor that if this person is embezzling, they’re going to see more manifestations than one instance three years ago. We try to help the dentist sort out what the employee is doing that should give them concern. We probably have a better knowledge than the dentist of what embezzling behavior looks like.

Once we mutually decide that an investigation should happen, the next thing we do is obtain their computer data. We don’t like to work on the dentists’ computers because they’re live systems and stuff is constantly changing. Plus, if we’re connected remotely to a dentist’s computer, there is a reasonable possibility that the staff member might realize what we are doing. One thing that we emphasize to every dentist we deal with is that an investigation has to be stealthy. The staff cannot know that you are doing an investigation until the process is complete and you have an answer. Because if you think there is fraud when there isn’t and you let the employees know that, you’ve destroyed the employment bond and rebuilding it will be close to impossible. On the other hand, if there is embezzlement going on, you want to spring a trap on the thief as opposed to the other way around. So stealth is important. What we do is we get a complete copy of someone’s practice management software data. So if you’re using Dentrix® (Henry Schein; American Fork, Utah), for example, there is a folder on your server that has all the data. We get it and bring it into our computer lab, where we analyze it using our copy of Dentrix and look for patterns that are consistent with embezzlement.

MD: Once you’ve identified that there might be some embezzlement going on, do you set the trap at that point? Or do you have to have another occasion or two to be able to make a strong case?

DH: No, most of the time at that point we can see what has gone on. A lot of times we’re helped by third parties. For example, if we see a situation where there was money billed to an insurance company but the money didn’t come to the practice. Then we can go back to the insurance company and ask where the check went. If it went into the receptionist’s bank account, then we know.

We also look at login names on the computer and who is logged into the practice management software. We also check if someone is coming and going at strange hours and if there is either an alarm system in the office or if there is some kind of building log that tracks access. If we can correlate transactions to a specific person’s access, then we have them. One message I’ll give your readers is that it is really important to have individual logins for your practice management software. Some offices have what I call the “unicode,” a single code that everybody uses to log in with, which makes it very tough for us to track who is doing the dirty stuff.

One message I’ll give your readers is that it is really important to have individual logins for your practice management software. Some offices have what I call the “unicode,” a single code that everybody uses to log in with, which makes it very tough for us to track who is doing the dirty stuff.

MD: Individual logins seem like a good preemptive thing to have in place, so employees know that anything they do on the computer is going to be able to be traced back to them.

DH: I highly doubt it will stop anybody from stealing, but it will make the job of pinning their hide to the wall far easier afterward. I’ll say the same thing about alarm systems in the office. I go into a lot of offices where there is one code that everybody in the office uses, including the office cleaners that were fired who used to work there three years ago. It’s important that everybody has their own unique login code for the alarm system, and that they are changed periodically. Because it stops employees from scooping up someone else’s code by watching over their shoulder when they’re entering it.

MD: That is another great tip. I love your example about the office cleaners who were fired three years ago. I would present individual login codes to the staff as a protection measure against outside theft more than internal theft, but also suggest that they keep the codes to themselves regardless. That way people aren’t looking at one another wondering who is stealing from the office or thinking that is why the practice is going through all the security trouble.

So if a dentist does think something funny is going on in their office and they want to give your company a call, what is the best way for them to contact you?

DH: We have one email address that we refer to as the “embezzlement hotline.” The email address is emergency@dentalembezzlement.com. We have an on-duty fraud investigator 365 days a year, and that email address is monitored by whoever is on duty. So if you send an email to that address on a Sunday, you will typically get a response the same day from an investigator who will say, “Let’s find a time when you are able to speak freely, and go from there.” We also have a phone number and other email addresses, but the absolute best way to get in touch with us if you have embezzlement concerns is emergency@dentalembezzlement.com.

MD: Any tips about where they should be sending that email from, just in case the embezzler is going through their email?

DH: If they’re not sure about their email security, the best advice I can give your readers is to set up a new Hotmail or Gmail account and send it from there. Just because we’ll know that one is secure.

For more information, contact David Harris at 888-398-2327 or by visiting dentalembezzlement.com. For immediate concerns about potential dental fraud being committed in your office, email emergency@dentalembezzlement.com.