A Disastrous Double-Arch Impression Tray – Case of the Week: Episode 32

When dentists attend my lectures, they are often fascinated by the clinical cases I show of what other dentists are sending in to Glidewell Laboratories. “Chairside Live,” our weekly web series, is a great opportunity for me to share these cases with dentists on an ongoing basis. Episodes can be viewed online and on demand at chairsidelive.com, or on YouTube and iTunes. If you aren’t already a viewer, I encourage you to start watching now for informative case examples from our lab and intriguing dentistry-related news stories.

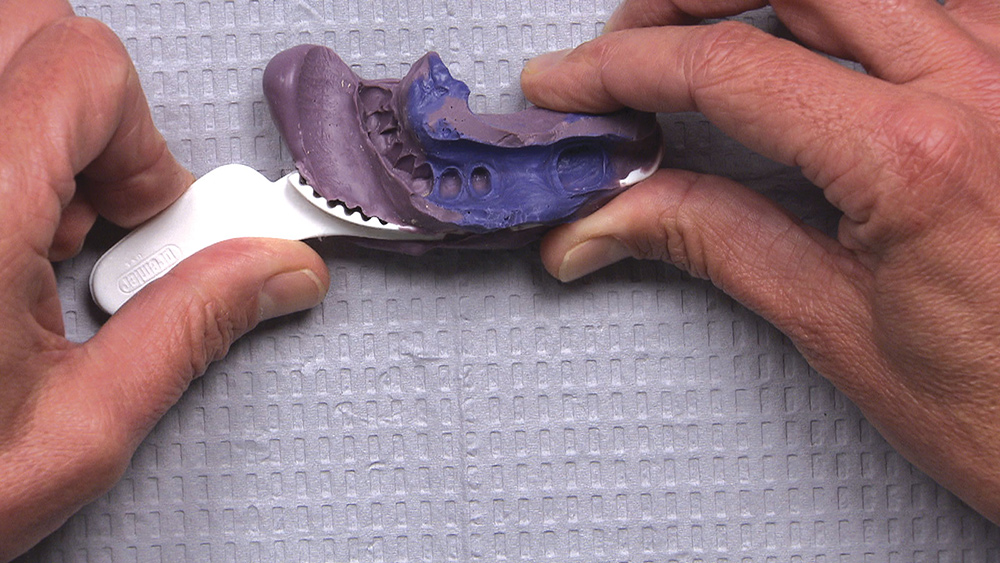

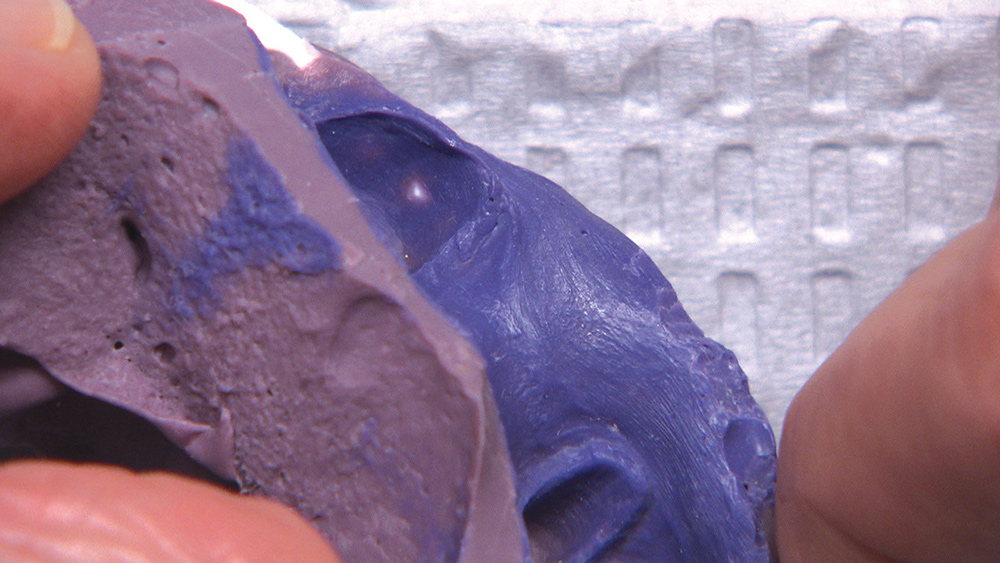

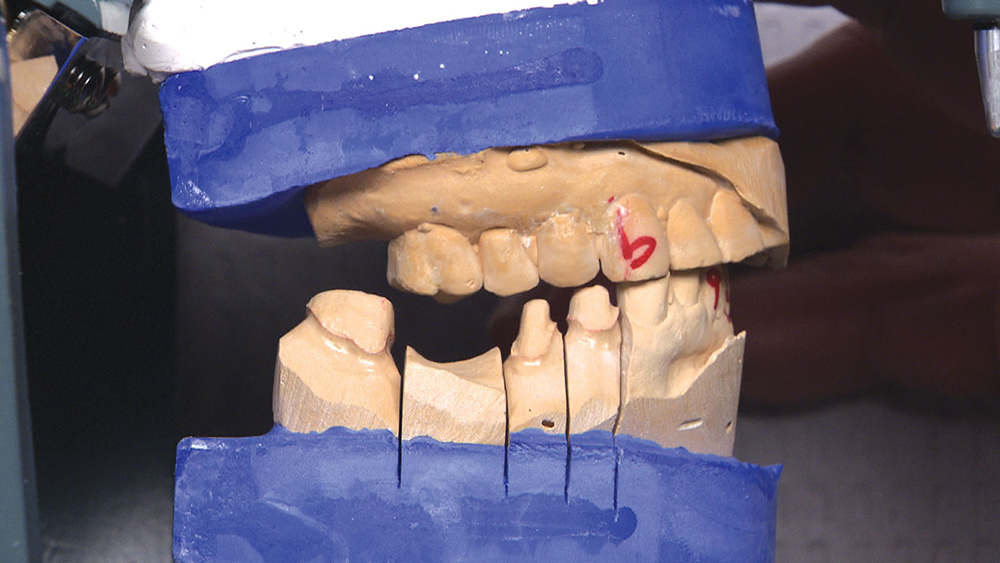

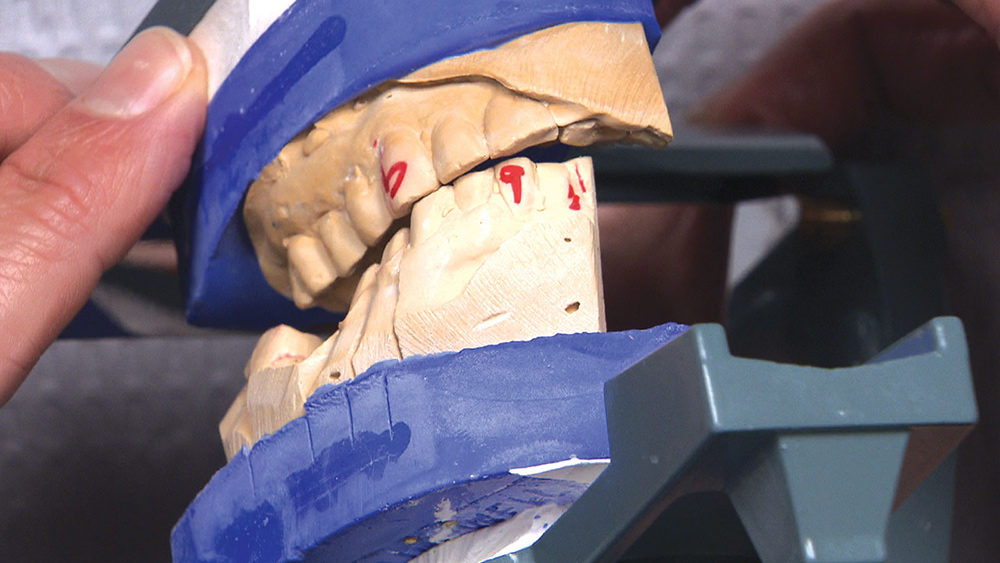

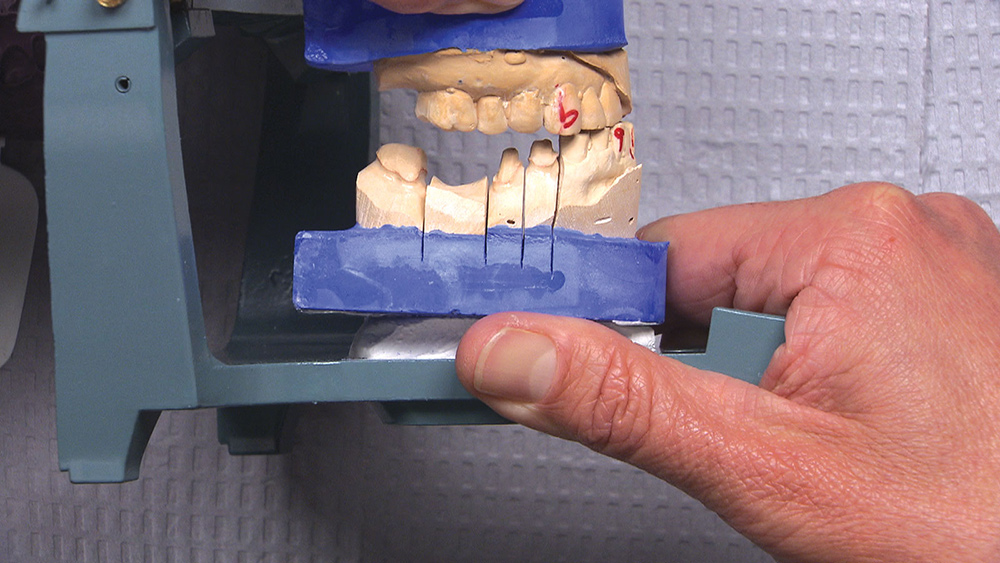

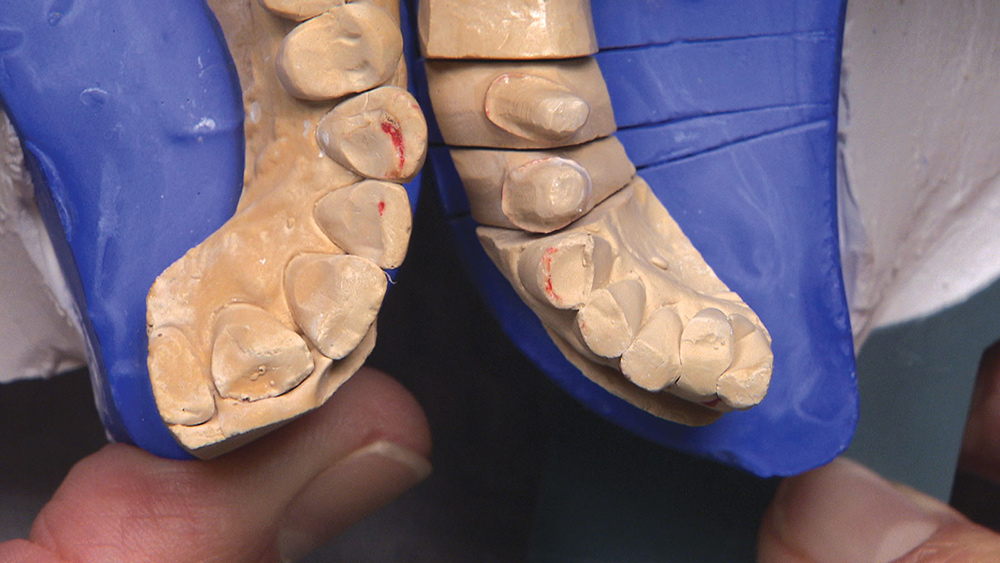

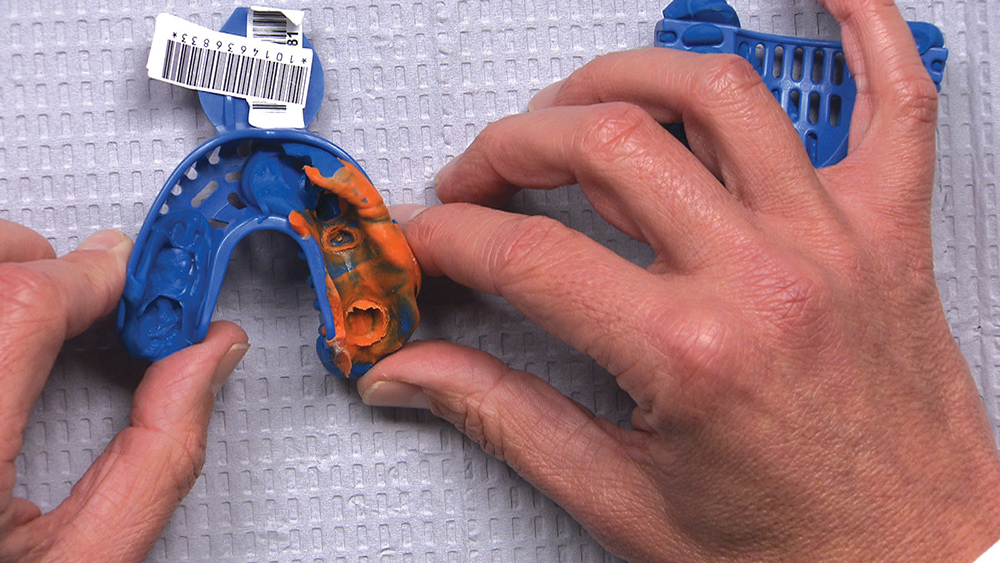

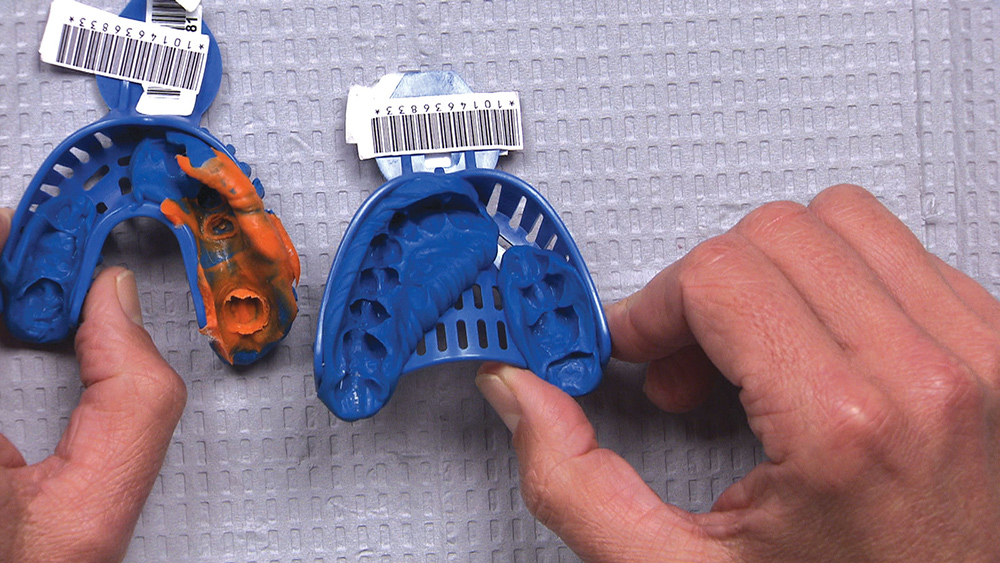

The video stills that follow highlight an interesting Case of the Week from Episode 32 that addresses what is probably my biggest dental pet peeve: when a double-arch tray is used for a bridge impression. While double-arch impressions can be suitable for one single-unit crown or two single-unit adjacent restorations, they should never be used for a bridge. A closer look at the case illustrates why.

While double-arch impressions can be suitable for one single-unit crown or two single-unit adjacent restorations, they should never be used for a bridge.

Conclusion

Using a double-arch tray looks so easy and seems so tempting when taking an impression on just one side of the mouth, but it very rarely makes for an accurate multiple-unit impression. Impression errors are especially important to avoid when dealing with multiple-unit impressions because any mistakes will be multiplied across the entire length of the bridge. Even if the bridge still fits the patient’s teeth, the bite will likely be off, which does not make for a happy patient. For any bridge case like this, you, the lab and your patient will be better served if you use a full-arch lower impression tray and a full-arch upper impression tray, as well as a bite registration between the opposing teeth and the preps.

Impression errors are especially important to avoid when dealing with multiple-unit impressions because any mistakes will be multiplied across the entire length of the bridge.

General References

For clinical technique tips on taking a bridge impression, watch “Chairside Live Episode 36: The Do’s & Don’ts of Taking an Impression for a Bridge.”