One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: 20 Questions with Dr. Bill Strupp

I have been looking forward to interviewing Dr. Bill Strupp since we started Chairside®. I find him to be a free-thinking breath of fresh air with some truly original ideas about the best way to accomplish quality restorative dentistry. Bill brings his particular brand of honest opinion to this interview, and some of the quotes I have made into laminated cards that sit on my desk. I hope you are as inspired to do quality dentistry by this interview as I was!

Question 1: I saw a lecture of yours 20 years ago, the year I got out of dental school. You told a story about making a commitment to quality restorative dentistry the day it came time to do a buccal pit restoration on your son, and you decided to do a cast gold restoration. Will you retell that story for our readers, please?

Dr. Bill Strupp: I would be delighted to do so. The year was 1980 and my son Bill was in for a routine cleaning and exam. I placed an explorer in the buccal pit of tooth #30 and it stuck. This was his first cavity. It was not soft and had I discovered such a lesion today, I would probably have cleaned it out with air abrasion and sealed it with resin composite. At that point in time, however, the restorative materials available to me were limited. In essence I had four choices: 1) amalgam, which was the material of choice for most initial restorations in my practice where cosmetic concerns did not exist; 2) resin composite, which could not be well bonded at the time; 3) gold foil, which would have required an intensive search through my storage shed for products and information on use of the material (I had not done one since graduating in 1969); and 4) a gold inlay, which is what I chose to do.

I prepared the cavity, did a direct wax-up, sprued it in the mouth to remove it from the cavity, invested it, burned it out, cast it, cemented it, cut off the sprue, and polished the gold. He still has the restoration after all these years with no evidence he will ever need to have it replaced.

The reason this story has importance to me is because when I went home and thought about it, I went into a full blown state of cognitive dissonance. I was placing amalgam left and right for all of my other patients, but when it came to treating someone that REALLY mattered, I would not use amalgam. I chose a better material knowing I would get a better result. The realization that I was shortchanging my patients was life changing. I perceived they did not value good dentistry enough to pay for it, and my perception was simply wrong. The only thing the patient needed was my recommendation to do the dentistry right.

The next day I went into the office and threw out all of my amalgam and the equipment I used to place it with. I have not done an amalgam in my practice since. I must admit that there were many times when I almost went back to it, but I became adept at doing conservative gold castings. And the income from them became a significant benefit for many years. The rut I had climbed into during and after dental school became a superhighway to success because of the choices I made stemming from this experience.

Q2: I remember that you were initially very skeptical about all-ceramic restorations. What changed your mind, and how do you typically use them in your practice?

BS: It wasn’t that I was skeptical, I had been burned! I bought a DICOR® casting machine in 1985 and produced about 1,000 units until I stopped doing them in 1988 due to a catastrophic fracture rate. Many of the units I placed were with zinc phosphate cement, as recommended by the manufacturer. Over 500 failed within 10 years, and the impact on my practice and bottom line was disastrous. So I would say I am cautious when it comes to believing manufacturers. I am more cautious than skeptical. Had I bonded the majority of those restorations in, the results would have been better, but there were still issues with DICOR that made it a bad material.

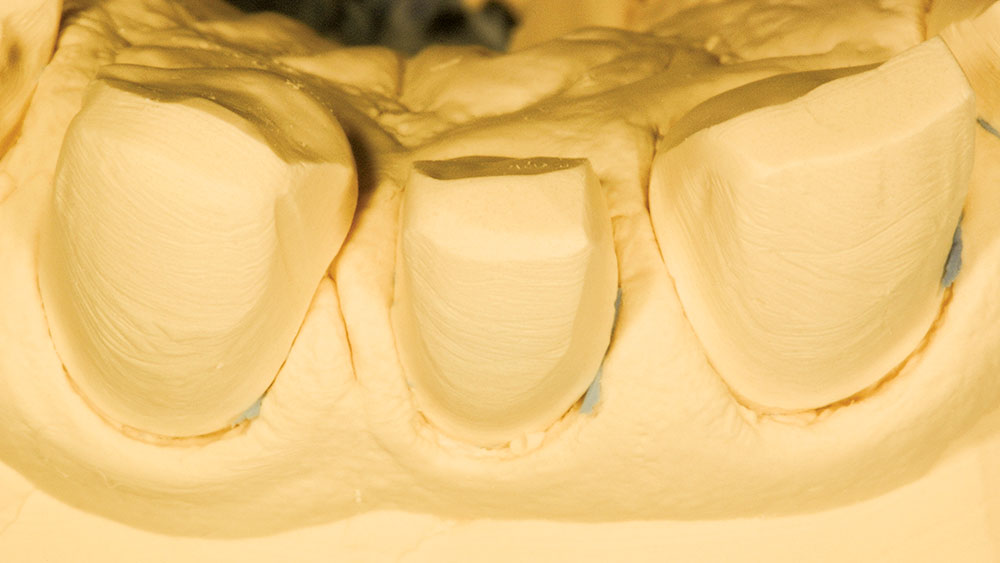

I aggressively started doing all-ceramic restorations using feldspathic porcelain fabricated on refractory dies in 1993, and I have done about 10,000 units since that time. I use the material throughout the mouth for those patients that require the ultimate in esthetics. The primary benefit is preservation of biology, since the prep design allows reduction of as little as 0.1 mm, whereas many other ceramic systems require from 0.7 to 1.5 mm. I prefer to use these restorations from bicuspid to bicuspid and use stronger materials on the molars. The fracture rate over this time has been between 4%–5%.

Q3: I have been placing zirconia-based restorations for almost seven years now. While they haven’t always been the prettiest restorations, the frameworks have performed extremely well during that period of time. What is your experience with zirconia, and do you use it routinely?

BS: Zirconia is an interesting material. I bought a Procera® Piccolo scanner from Nobel Biocare and started doing custom zirconia abutments for implants in the critical cosmetic zone several years ago. In addition, I scan my own copings for single units. I have placed over 200 units and have found the learning curve to be fairly steep. The new software has allowed us to fabricate copings that are 0.4 mm thick (anterior teeth only). Coupled with my improved preparation designs and my technicians’ demand for tighter fits, the restorations are beginning to challenge metal ceramics. If the price of gold continues to escalate, I predict zirconia will become as widely used or more so than metal ceramics. The key to the material from a cosmetic perspective is to use translucent, highly chromatic, substrate-blocking porcelain as the first layer of porcelain on the restoration to control the brightness. In addition, the opaque liners should all be discarded.

From the laboratory point of view, two things are ultra important: 1) Do not overheat it; and 2) Provide appropriate support for porcelain in the framework design. Most of the fractures I have seen resulted from the lack of porcelain support. Just as in metal ceramics, porcelain thickness greater than 2.0 mm is contraindicated.

The last point about zirconia is how it is bonded. Current research supports bonding to decontaminated and CoJet™ sand abraded zirconia that is primed with Clearfil® Ceramic Primer and bonded in with PANAVIA™ F 2.0.

Q4: I have to take a very scientific approach to tooth preparation if I even want to try and attempt preps like yours. Do you have a specific preparation technique you use?

BS: The approach I have found to be the best is to prepare the tooth based on the requirements of the restorative material selected. Providing enough room for the selected material is fundamental to success. I prepare teeth with copious water yet marginate dry and supragingivally, use sharp diamonds on concentric handpieces at ultraslow rpms to prepare the margin, use magnification (6x) and tons of light. Other than that it is a matter of art. After placing more than 45,000 units of crown and bridge in my career, the art part has gotten easier.

Q5: How did you happen to come up with the holy triad, and has it changed at all over the years?

BS: In the mid-’70s, I started using Dial® Surgical Scrub (4% chlorhexidine gluconate) to clean off the preps before I cemented my provisionals, and noticed a significant decrease in sensitivity. I started using it before final cementation with glass ionomer cements and noticed a similar decrease in post-cementation sensitivity. When dentin bonding came along sensitivity was a significant issue. I started using 4% chlorhexidine gluconate to minimize that and it worked. Over the next decade or so, I added Tubulicid from Global Dental Products because Branstrom had shown microbial kill in the tubules with a 60 second scrub. Later, after reading research by [Dr. Charlie] Cox, I added Clorox® to the disinfection scrub regimen.

It occurred to a physician many years ago that hand washing before delivery would prevent dead babies. It occurred to me that tooth washing before cementation would prevent dead pulps. I still kill pulps with crown and bridge dentistry but the numbers are no longer one in 10 like it was before; it’s more like one in 1,000 now. I attribute this to an overall protocol of pulp protection throughout the entire crown and bridge process.

Q6: Let me ask you a follow-up question on the holy triad. You’ve been teaching that for a long time. Have you met dentists who think, for example, using Clorox is a bad idea or sounds crazy?

BS: Nobody ever really questioned me on Clorox. Guys like [Dr.] Ray Bertolotti say, “No, you don’t need to do that because this bonding resin is antimicrobial.” And although there is an element of antimicrobial activity, certainly that’s a major reason for using the triad. Dr. Maria Pappas published in the Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry in June of 2005 an article that showed she enhanced bond strength significantly when using the pre-disinfection approach of the holy triad. So we get better bond strength and you don’t do as many root canals. However, it’s the only published study that’s ever been done — no one has ever published another one — so it really is a meaningless study.

I can tell you that from about 1978 or 1979, when I first started to use chlorhexidine, the degree of pulpal complications and death began to disappear. As I evolved into a more cognitive dentist, from the perspective of having microbes in the dentinal tubules, I began to research ways of eliminating the microbes from getting into the tubules because I figured that was the access to the pulp. And if we could stop that microbial ingress through the tubules, then we wouldn’t lose any pulps. Over that time frame I’ve gone from killing teeth like crazy in crown and bridge, especially in the days of glass ionomer cements, to today when it’s just so infrequent. It almost never happens. I can count on one hand the number of teeth that have had to have root canals in the last four to five years. It literally is just not an issue anymore. And that’s including all that my periodontist, Dr. Danny Melker, reshapes. Years ago we killed a bunch of teeth, so I do believe that process of antimicrobial management of the tooth — from the time you begin to treat it until you’re done with it — makes a difference in how many root canals you have to do.

I can tell you, in my own mouth, I know that for a fact because I had a very famous occlusal-oriented dentist place some gold castings for me back in the ’70s. And he left some amalgam under them, which drove me nuts. The teeth cracked because the amalgam expanded, and I was pretty sure I was going to have to have a root canal. I had one of my students come to my office and cut the inlays out, take the amalgam out, take the decay out, and do core buildups with my protocol on my teeth, and then put gold onlays onto my teeth. Within a matter of three months, the sensitivity to hot, the sensitivity to cold, and the sensitivity to biting pressure was gone. And that was 15 years ago. So I know that if you give the pulp a chance to live, like Dr. Charlie Cox says, it will. You’ve just got to keep all the bad bugs and things away from it.

Q7: I remember an article you wrote many years ago that listed 20 reasons to do buildups. Can you go over the top three reasons for me?

BS: Without question, the primary reason for core buildups is pulp protection. When microbes are denied access to the pulp, especially in deep cavities, less pulp death occurs. Just as important, cores make the process of restoring the case perio-restoratively predictable. Most of the cases I treat perio-restoratively involve removing failed crown and bridge and caries, both of which are usually in violation of the biologic width. When I do a core buildup and place a surgical provisional for my periodontist to remove at the time of surgery, he has a visual point that can be measured 360 degrees around the tooth that tells him precisely how much osseous surgery is required. He knows that the core must be 3 mm coronal to the bony crest.

If caries or an old restoration with caries under it is present at the time of surgery, he must guess where the final margin of the restoration will be relative to the bony crest. Invariably excess bone removal will occur when guessing about biologic parameters at the time of surgery. In essence, cores program periodontal surgery in perio-restorative cases. Cores block out dark substrates and allow the use of translucent all-ceramic restorations that look like natural teeth instead of crowns. Less precious metal is required when cores are done.

Financially, core buildups can increase the average dentist’s income by $300,000 a year.

Q8: I can’t begin to describe how disappointing it is to see some of the inadequate impressions we get here at the lab. Spend a couple of minutes telling our readers about your impression technique.

BS: I have several concepts that help to make impressions more predictable. The first is placing all margins supragingivally. Make sure you understand that no impression material works as well wet as it does dry, with the exception of reversible hydrocolloid (which very few dentists use). This means the cord must be dry before it is removed and the impression material is injected. Cord placement must be done atraumatically because cord placement trauma is the primary cause of bleeding when the cord is removed. Epinephrine must be used to control hemorrhage, but soaking the cord in Hemodent™ is a prerequisite for its use. Custom trays are required in 90% of cases. Contaminants such as glove powder, gloves, grinding debris, bonding materials, and a host of other chemicals, including some astringents, inhibit the set of impression materials, which causes them to tear off in the sulcus. The sulcus must be cleaned before placing the retraction cord. Quadrant impressions are a severe compromise. Putty/wash impressions are inferior to heavy body/light body impressions. And finally, a crown and bridge impression is merely a reflection of the dentist’s integrity. Nothing more, nothing less.

Q9: You got me to start using Durelon™ as a temp cement years ago. This has really helped, especially because I got a sonic scaler, as you suggested, to clean the cement off the teeth. Can you talk a little about this technique?

BS: Durelon is just another part of the antimicrobial protocol. It kills microbes, is relatively insoluble during the short provisionalization phase, minimizes lost provisionals, soothes the pulp, and is easily cleaned off with sonic scaling and air abrasion. One of the most pulp positive events ever to occur in my practice was when I talked my periodontist into using Durelon to recement provisionals after surgery. Postsurgical sensitivity decreased tremendously when Durelon replaced soluble temporary cements (which promote microbial growth).

Q10: Do you still use cast gold as your restoration of choice for second molars?

BS: Cast gold is the restoration of choice when cosmetics are not an issue, especially in the second molar areas that absorb 55% of the biting forces. Many patients refuse gold, even after I explain the fee for all-ceramic and gold is the same but that gold will never fracture and the shade will always be spot on. In the instance where the tooth only needs a partial coverage restoration, I am hesitant to mutilate the tooth to place a crown on it just because the patient does not want gold. In such cases, I still use a partial coverage restoration but make it in all-ceramic, with the idea cemented in the patient’s mind that fracture is more likely with the all-ceramic restoration and that a fee to replace it will be required.

Q11: Do you find yourself doing many porcelain veneers in your practice?

BS: I place about 600 all-ceramic restorations each year. More than two-thirds of those are veneers, or stated better, partial coverage restorations. Full crowns mutilate teeth, pulps and soft tissue. Partial coverage restorations are indicated on every tooth requiring restoration, except the ones where a crown has already been done. Obviously, in this case, another crown is required.

One of the most important points I stress in my lectures is the preservation of biology. When all of the tooth structure is gone it is not easily replaced. It is better to keep the tooth structure and modify the restoration rather than the other way around.

Q12: What are your current cements of choice for routine crown and bridge and bonded restorations?

BS: I only use PANAVIA F 2.0 Light. I bond in every restoration I do and have not used conventional cements, except for provisionals, this century.

Q13: I had the opportunity about two years ago to get in contact with your periodontist, Dr. Danny Melker, through Dentaltown®. After begging him to let me come out and watch some of his perio surgery, I flew out there to observe. And it just so happened to be two of your patients he was working on that day. He didn’t set it up that way and you didn’t know it. But I have to tell you, and make sure our readers know, when Danny took the provisionals off and started the surgery on those two random patients of yours, the preps on those teeth looked exactly like the preps you show in your lectures. Every tooth had a core buildup on it; the tissue all looked like it was supposed to. He went in and did his root reshaping and smoothing on those areas and then put the temps back on. That was the day I found out for sure that you were the real deal. Not that I had any reason to think otherwise!

BS: That’s nice of you to say. Over the years Danny and I have worked really diligently on that protocol, in terms of trying to come up with a degree of predictability in our perio-restorative crown and bridge. To tell you the truth, when we varied from our protocol, we’d get into trouble. I try to do everything that he needs me to do every time, and he tries to do everything that I need him to do every time. Obviously nobody’s perfect. But if you took a thousand of our cases and put them all side-by-side, you’d find a couple of percentages that would not look as good as you’d like and a couple of percentages that look better than anything you thought that God could do. The rest of them are just almost perfect. There are shortcomings in everything, of course. You know, you have complications — patient factors and things of that variety. But, by and large, we just don’t have problems with our crown and bridge. I believe that in this day and age, this perio-restorative issue is one that we as dentists are going to have to address in a very definitive fashion. I think if we allow ourselves to continue to do things like we’ve always done, that one day we’ll be faced in court with some fairly harrowing lawyers that may take away some of our assets. So, I do it not because I worry about getting sued. I do it just because I just think it’s better for the patient not to be in a state of disease.

Q14: I agree that it’s better for the patient. It may turn out that biologic width violation is at the center of malpractice lawsuits in the next 20 years. But one of the initial things I noticed when I began watching what you were doing and trying to follow it was the amount of commitment it takes — not only on your part but also on the part of the patient. And oftentimes, for anybody who subscribes to your online newsletter, you’ll see a case and the patient will be referred to two, maybe three, different specialists based on what’s going on as part of this team approach. So there’s a real commitment on your part not to just jump in and prep six or seven crowns and get paid for it, but to really commit yourself to doing the entire case. You have to practice some delayed gratification as the patient sees these other specialists. Do you see why it may be difficult for a dentist to swallow that concept?

BS: I do for those who have not done it. I don’t for me, though, because I made a commitment to do things a particular way, and that now has become routine in my practice. Because of that, the complexion of my practice has changed. Years ago, I was out there just throwing in crowns like everybody else. You try and make a living. You get out of dental school and you have all these debts, so you try to get things done quickly. Somebody walks in the office and you say, “Let’s go put a crown on it.” All of a sudden, you look at the case two or three years down the road and you’ve got complications that you’d never even thought about. The patient doesn’t really benefit at the level that I think they should be, considering it’s supposed to be top-quality care.

As things evolved over time, I would tell patients: “Let’s don’t necessarily do all this treatment today. Let’s get a treatment plan that’s a comprehensive plan, a plan that makes sense for you in terms of your health long-term. And then let’s find out how much of that elephant we can sit down and eat in one meal. Then, if we proceed to do this treatment plan — which is an ideal plan — over a period of time (and it may be 10 or it may take us 20 years to do it), then when we finish this treatment plan, the treatment will have been done appropriately. You won’t be in a situation where I did a bunch of treatment and the only person that could eat better when we were all said and done is me.” People seem to identify with that. And I use that a lot, by the way.

The bottom line is that at this point the patient is not under any obligation. They haven’t had any treatment done when they go for the consults to see what is wrong and what needs to be done to correct it. The truth of the matter is that when they go to my specialists, the specialists sell the case for me. I really don’t have to sell a case. Rather, patients walk back into my office and say, “Well, I think we ought to start with the lower.” How tough was that? Because it’s a comprehensive plan, we treat the endo first, we put cores and temporaries in place. I know the extent of the pathology that goes into the biologic width at that point in the game (and so does Danny Melker). He goes in and does his root reshaping. (Or he’s calling it biologic shaping now, which is probably a little more accurate term but not quite as sexy as root reshaping.) When he’s done doing that, all I have to do is stay away from what he did. My job as a restorative dentist becomes inordinately simply because I just stay away. I finish my margin above the tissue, just a fraction of a millimeter above the tissue. Literally equal to the tissue but yet not below. Then I use whatever restorative material the patient will let me use. My idea is that gold is the best. But if the patient wants porcelain I can make porcelain, and I can make it look coming off of a tooth with one-tenth of a millimeter of reduction, exactly like a natural tooth. You can’t even tell there’s a restoration on the tooth.

Q15: You make a great point. Even if the patient had gone to their former dentist two years ago and the dentist said everything looks good or you need one crown, they now come to you and you talk about needing 13 or 14 crowns. The patient might be suspicious, especially when you’re one person versus their old dentist. But by the time they have seen your team of specialists, they’ve now heard the exact same thing from three different, well-educated dentists. It’s like they get a second, third and fourth opinion. And like you said, by the time they come back to you, they say, “Let’s start on the lowers.” So really, you’re right; they do end up selling the case for you in a sense because it’s three other independent doctors who tell the patient the same thing.

BS: I left out one of the parts that’s really critical to the whole ordeal, and that is the way patients can actually get into the practice. Nowadays, my practice may be a bit different in that a lot of people come in and say, “Sit down, here I am, do me, I’m ready to be done,” that kind of thing, because there is so much cosmetic-driven stuff out there. But I would say a large percentage of my practice is still patients who come in and just want their teeth cleaned. They don’t know me from Adam’s housecat. They are not necessarily the kind of patient that walks in, sits down and says, “Here’s $50,000 — fix my teeth.” Typically, what happens is the hygienist broaches the subject of the quality of dentistry that’s in there. She looks around and she says, “You know, I’m really concerned about infection”; she teaches them about home care; she teaches them how the dentistry in their mouth is preventing them from getting the home care done they need to get done. And she’ll see them two, three, four times over a period of a couple months to try and get rid of the infection. When it’s obvious the infection will not go away, in spite of her effort and the patient’s effort, at that point in the game it’s pretty easy to say: “Look, we’ve got an issue going on with infection. We know that infection is correlated to all these other systemic issues. And we really need to do something a little more definitive.” The patient might say, “Well, these crowns are only four or five years old!” She’ll reply, “But the way they were done or the way they were cemented or the way the laboratory made them gave us a result that is just not acceptable.” I’ll never throw anything disparagingly on any dentist; if anything, I’ll always chop up the laboratory. I’ll say, “Yeah, the lab just didn’t do a very good job with this,” which is less insulting to the profession as a whole than to say, “Boy, the last dentist sure messed this up!”

Q16: I agree that the laboratory probably didn’t do a very good job. But if we go one step back, we’ll find out the dentist didn’t send in a very good impression.

BS: That is exactly the reason the laboratory didn’t do a very good job! The problem is the impression, but I don’t tell a patient that! I’ll just simply say: “This condition that I find is not one I’d want to continue in your mouth, and I’d like to have that changed. So why don’t we go ahead and do a comprehensive evaluation, I’ll send you over to my specialists and see what they say about it, I’ll go over the treatment plan, and we’ll come back and we’ll see what we want to do.”

Q17: You don’t even start talking crowns at that point?

BS: No. When I do the comprehensive exam, I say it aloud to my dental assistant. And I say to my dental assistant: “I want to do full coverage on this tooth, partial coverage on this tooth. I want to take that tooth out. I want to put an implant in. We’ve got a problem with the esthetics, with the plane of occlusion. I’ve got this issue. I’ve got that occlusal issue.” I’ll say all these things, she’ll write all of these things down on a record, and then she’ll have a treatment plan. Then she’ll write a letter, it’s a long letter typically, to all three specialists that will say, “Dr. Strupp saw his wonderful patient Rick. He’s missing number 14, he’s got a bridge, number two abutment is loose…,” so on and so forth. This is our treatment plan. “If you feel that we’re trying to save a tooth that should be extracted, then let us know what your opinion is.” But I don’t send patients over there with a definitive plan. My treatment plan is an evolving plan based on what my specialists say. If I hear back from my endodontist that I’ve got a vertically split number 19, that tooth becomes an implant. And even if Melker says I can reshape a tooth and keep it, if it’s vertically split, I don’t want to deal with it and he doesn’t want to deal with it. The issue is: what is the actual treatment plan that we’re going to do, and how fast can we get this done? The only limiting factors are time and money. Most patients truly want to have what’s best for their health. If you ask a room of people, “What is the most important thing in your life?”, 95% of them will say their health. With my patient base, which is probably an older patient base than yours, the bottom line is that they are interested in health. They don’t want to be wandering around with things that actually create issues for their health — they’d like to do things to get it straightened out. That’s what I’m all about. I’m just offering opportunities.

Q18: In your impression protocol you said that, “Epinephrine must be used to control hemorrhage, but soaking the cord in Hemodent is a prerequisite for its use.”

BS: I use number seven Sil-Trax® from Pascal with epinephrine in it.

Q19: I am a big Epi cord fan, but it seems that at every lecture I do dentists will come up and tell me I am playing with fire. What has your experience with Epi cord been like for the last 30 years?

BS: I’ve used the epinephrine impregnated cord for pretty much every unit that I’ve ever done in my career. Early in my career, I didn’t soak the cord in Hemodent. I did use much larger cords, of course, that had much more epinephrine in them. And I got a couple of systemic responses with patients after I packed 14 units of bleeding, raw, red gums because, back in those days, we were using hydrocolloid impressions and subgingival margins. You had to beat the tissue to death to get it out of the way. You had to beat it to death to cut the preps subgingival. We used rotary gingival curettage, to describe Rex Ingram back in the ’70s, with hydrocolloid impressions. Ultimately, with a big slab of fresh bleeding gum tissue, you could get a systemic response. But in the late ’70s, early ’80s, I realized that you really ought not be in the tissue, a result of many talks and challenges between Danny Melker and myself. Because I worshipped occlusion — I believed in everything ever said about occlusion by certain camps around here, there and yonder — I made no bones about it. I was totally involved in doing reconstruction based on occlusal need, and Danny challenged everything by saying: “You know what, this is all about infection. If you get rid of the infection and the occlusion is within the envelope of where that patient functions on a normal basis, you’re not going to lose any teeth!” I didn’t believe him at first, but over time I’ve grown to believe him. I would have to say that I haven’t had a systemic reaction to epinephrine in the last 30,000 units of crown and bridge that I’ve placed, probably since somewhere in the time frame of 1978 to 1979.

Q20: You have often said that partial coverage restorations are indicated on every tooth requiring restorations, except the ones where a crown has already been done. Can you go into a little more detail on that?

BS: The only exception, other than the fact that it’s already got a crown on it, would be if it had pathology that was 360 degrees. But rarely do you see the palatal side of the tooth that has gingival decay; it’s usually the buccal side. Lingual restorations in my office are usually three to four millimeter supragingival. And I can control every element of occlusion, every element of esthetics, every element of making a restoration fit. I can do everything I need to do with a buccal three-quarter type restoration. There is literally no reason to go into that subgingival situation. In the back of the mouth, I like to do onlays. I don’t like to be anywhere near the tissue on the facial of any of the teeth in the back, if I can get away with it. Now you can’t do that on the upper arch, but you can most certainly do it on the lower in most cases.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: I love guys like you and Gordon [Dr. Gordon Christensen], who are willing to tell it like you see it, especially in print.

BS: It doesn’t really bother me because I really don’t care what people think about me. What I’m interested in is making dentistry a better profession. I truly believe that dentistry is one of the greatest professions on earth, and over the years we have been bastardized by manufacturers and clinicians who are just telling lies. It just bothers me. I think integrity is a very important aspect of life, and if we don’t have integrity then I think we don’t really have much to offer people. MD: Bill, that was fantastic, and I look forward to seeing you at your course in Santa Barbara this summer. Thanks again for your time.

BS: Thanks, Mike. Take care and stay well.

If you would like to contact Dr. Bill Strupp, call 800-235-2515, visit strupp.com or email Bill@Strupp.com.

DICOR is a registered trademark of DENTSPLY International (York, Pa.).

Procera is a registered trademark of Nobel Biocare (Yorba Linda, Calif.).

Clearfil Ceramic Primer is a registered trademark of Kuraray Dental (New York, N.Y.).

Dial Surgical Scrub is a registered trademark of The Dial Corporation (Scottsdale, Ariz.).

Clorox is a registered trademark of The Clorox Company (Oakland, Calif.).

Sil-Trax is a registered trademark of The Pascal Company (Bellevue, Wash.).

CoJet and Durelon are trademarks of 3M, 3M ESPE or 3M ESPE AG (St. Paul, Minn.).

PANAVIA is a trademark of Kuraray Dental.

Hemodent is a trademark of Premier Dental Products (Plymouth Meeting, Pa.).