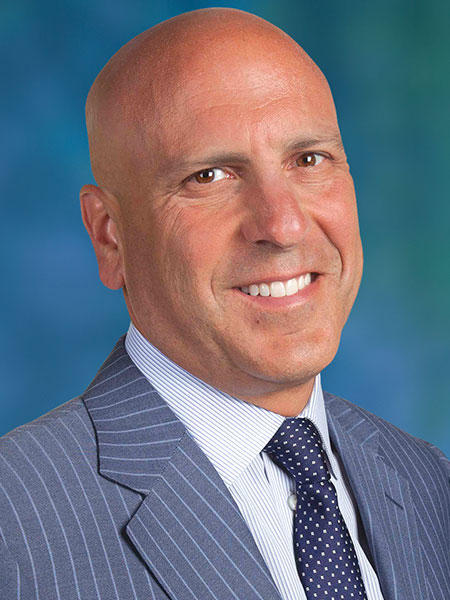

One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: Interview of Dr. John Harden

Dr. John Harden is a Glidewell Laboratories customer and fellow speaker, who will be presenting at the 2013 CDA meeting in Anaheim, California. After learning that his program will be on hospital dentistry, it dawned on me that I had never interviewed a dentist in Chairside® who specializes in this area. John has hundreds of stories about the type of unpredictable cases that can be thrown at you when working in the hospital setting, and he recently took the time to sit down and share a few. Enjoy!

Dr. Michael DiTolla: In Chairside magazine, we haven’t had the opportunity to talk to someone who does a lot of hospital or sedation dentistry. Tell me a little bit about your background, especially what you did after dental school that led you to where you are today.

Dr. John Harden: I graduated from the Medical College of Georgia School of Dentistry in 1978, and then I practiced for about five-and-a-half years in downtown Atlanta. I met my present wife, who is in anesthesia, and I got very interested in anesthesia. So I went to Chicago to the Illinois Masonic Medical Center, which is a University of Illinois teaching hospital, and I did a residency program in anesthesiology. The program accepted one dentist with the physicians, and I went through with 17 physicians.

After I finished that program, I came back to Atlanta and started going around giving anesthesia for other dentists. I also worked in a large clinic and, in about 1987, started up another practice. And I continued going around giving anesthesia for other dentists in their offices. But as business built up, I just didn’t have time to do that. I had to spend more and more time in the office, and of course we gave anesthesia for our own patients. This was mainly deep IV sedation; we didn’t give any general anesthetics at all. I got involved with hospital dentistry at Emory University Hospital, which is where I am right now. As the years went by, we started doing more and more hospital dentistry, and that’s our prime focus right now.

MD: When you were doing anesthesia for other dentists, what type of procedures were you mainly going to their offices for?

JH: Extraction of third molars and periodontal surgery, and sometimes other miscellaneous general dental procedures. But those are the main things we did. We had a lot of general dentists taking out third molars. I would carry all of my equipment with me, including my own oxygen supply. I didn’t want to take a chance on anything. We mainly did sedation with Versed (midazolam) and fentanyl.

MD: What was your experience in terms of safety over those years? Since you were doing more deep IV sedation as opposed to general anesthesia, it sounds like it was probably a pretty safe procedure.

JH: It was a very safe procedure, and we never had any problems at all. I basically did it the way I was trained as a resident in Chicago. We never had any adverse reactions. Every now and then we had a few patients where once I got on site I realized we couldn’t do the case. There was one case where I showed up to give anesthesia on a guy who’d had a heart attack a couple of months before. I realized that we weren’t going to be able to do anything on the patient, and that we needed to wait at least six months and get clearance from a cardiologist. But, overall, we had a great safety record.

MD: So were these mainly GPs or surgeons taking out these wisdom teeth?

JH: These were mainly GPs that I gave anesthesia for. They were doing third molars and other miscellaneous procedures. I’ve had periodontists and prosthodontists come to my office and have me sedate their patients. Over the years, we’ve gravitated mainly to hospital dentistry and sedation.

MD: I know a lot of general dentists who don’t enjoy taking out four third molars, especially if they’re partially impacted. I always thought that their discomfort came from the surgery itself, but I wonder, if those dentists were able to have a patient be in deep IV sedation, would they not feel a little more confident taking on those cases? I think part of their discomfort comes from the patient being awake.

JH: They do much better with IV sedation — absolutely.

MD: Don’t you get the feeling that more dentists would probably attempt that procedure if they had someone doing IV sedation in their practice?

JH: Absolutely they would, because many times you get too involved with the procedure and you can’t adequately monitor the patient. Sometimes it’s difficult to do both. Most general dental procedures are rather long as opposed to oral surgeries, where the surgeon goes in and gets out four third molars in 30 to 45 minutes at the most.

MD: And I’d assume that even those oral surgeons would take a lot longer than 30 or 45 minutes if the patient was awake.

JH: Oh, absolutely. There is no question about that. Third molar surgery is a very difficult surgery when you have bony impactions. There’s a lot of post-op pain associated with it, too.

MD: So how did you get introduced to hospital dentistry? Like most of our readers probably, I have been involved in very few hospital dentistry cases over the years.

JH: When I was in Chicago doing anesthesia, they had a big general practice residency program there that did a lot of dentistry for the handicapped. I used to put a lot of those patients to sleep with full-blown general anesthetics. So I watched the general practice residents and got to know them well and decided to do that when I came back to Atlanta. I applied to be on the medical staff and started doing hospital cases in 1988. And we’ve done many hospital cases over the years — the sickest of the sick. And in as much as Emory University Hospital is a teaching hospital for a major university, they will treat anybody. It doesn’t matter how sick they are. They can handle anyone.

On my website is a list of many of the different types of cases that I’ve done. One particular type that we have enjoyed doing is renal transplant cases, where you have to clean the patient up prior to the transplant and write a letter certifying to the transplant surgeon that there are no sources of dental infection. But the problem with these patients is that they often have out-of-control hypertension, in that top 5%, where it’s called malignant hypertension. You really have to treat them in an operating room; there is no way you can manage it in the office, because medication has to be given to keep their pressure down. Many times these patients have to go to the ICU for blood pressure control. The last case I did was a female patient with end-stage renal disease, hyperparathyroidism and out-of-control hypertension. We had to give medication in the recovery room because she was over 200 systolic and 120 diastolic. If you typically do patients like this in the office you can get into real trouble. Many times you have to have a nephrologist, a kidney specialist, on standby to manage the hypertension after the OR case. So those are some of the types of patients, but I actually got into that by watching the general practice residents in Chicago when I was an anesthesia resident. So now we do it routinely. I get referrals from very difficult patients, such as those with Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, developmental delay and severe cardiac disease.

MD: Are you providing the anesthesia and doing the dentistry on those cases?

JH: Oh, no. The Emory University School of Medicine runs the anesthesia there and they have attending anesthesiologists. But most of the anesthesia is given by physician assistants (PAs) in anesthesia and Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs). The PAs in anesthesia have a four-year college degree and have completed a two-year PA training program. The CRNAs have a B.S. in nursing and two to three years of anesthesia training. They are both very, very good. So they give the anesthesia and I just do the dentistry. I have an assistant who is credentialed in the hospital system who goes with me and assists me in doing these cases. They can last anywhere from two or three hours to seven or eight hours, when we have a lot to do. Many times when we go down there we really don’t know what we’re going to have to do, because we can’t examine the patient and they’re unmanageable in the office. So we do the exam — I have digital radiography in the operating room and we take all the X-rays there and formulate the treatment plan — and then proceed to do everything.

MD: So you walk into these anesthetized cases, where you’re trying to cram in three or four appointments, and you have no idea what you’re going to be doing?

JH: Yeah, we carry all the operative stuff. We carry endo gear with us. I carry an Aseptico® endodontic handpiece (Aseptico Inc.; Woodinville, Wash.) and the SybronEndo Twisted Files™ (SybronEndo Corporation; Orange, Calif.), and I do the endo from start to finish, whether it’s anterior, bicuspid or a molar.

MD: Are you also doing extractions?

JH: If there are extractions, I’ll have an oral surgeon come in and take out the teeth at the beginning of the case. They’ll suture them up and leave, and then I’ll do their operative. I do take teeth out though, but the problem is, as in a general practice, I’m too busy doing restorative. As another example, a young lady I’ve been treating for some time, who truly is dental-phobic, said, “John, I want veneers and ceramic crowns on the upper front six teeth.” I said: “Sure, no problem. Can you handle the office?” She said, “I cannot, we must go to the operating room.” So we went down there and did the preps and impressions. The crowns were all done by Glidewell, by the way. Glidewell does great work!

MD: Thank you!

JH: I’m not a “Michael DiTolla” from the restorative standpoint, but we do enjoy doing it. I did two ceramic crowns and four veneers on her and they came out great. Only had to take one impression, which is not unusual, but (laughs) we were lucky on that one. Let me tell you about a case we did late last year. The patient was 35, but when she was two or three months old she had an astrocytoma resection, a brain tumor. She survived, but obviously she had a lot of neurologic deficits. So we took her to the OR and did two ceramic crown preps on teeth #8 and #9, and we had to carry her back to put them in because when I touched her in the examination appointment she started screaming. So you see, the point is we get a lot of patients like that who are totally unmanageable. We’ve done a lot of restorative, and we’ve restored some implants. Now, periodontists would typically sedate them in the office and put the implants in. We just do the restoratives; I do not place implants at all.

MD: For the patients where I’ve had a dental anesthesiologist come in and do deep IV sedation, I’ve noticed that crown & bridge can be a lot harder to do on someone who is sedated. Do you find that to be true?

JH: Well, here’s the thing: If they have a full-blown general anesthetic, it is more difficult because you can’t take any triple trays on a lot of these patients because the tongue gets in the way. So, for instance, if I’m doing six, seven or eight units on the upper, I’ll take a full-arch polysiloxane impression on the bottom using heavy body and put it aside, then take a separate impression up on the top. Assuming all the teeth are present for the most part, usually you can hand articulate those pretty well without a record. It is more difficult though. I find myself saying “open up,” and the patients are asleep. But finally you realize that won’t work. It is more difficult when they’re totally asleep because you’re working in the airway. Now if they’re intubated with the nasal tube, like all of mine are in the operating room, there is nothing in the mouth to get in the way. Usually they’ll put a nasal tube in and put them to sleep, and I’ll drape the patient and put mouth props in and crank them open and just go to town. When I have endo to do, the rotary endo as you know is extremely fast, and with the Sybron TF files — there are only three of them — I can go in there and repair a bicuspid in about 15 minutes. And have it filled in 30 minutes with two canals. I share space with an endodontist, who has been boarded for years. We share space, but we have separate practices, and he’s taught me a lot of endo. That is where I’ve picked up a lot of my endo skills.

MD: What about seating crowns on sedated people? It makes it pretty difficult to check occlusion, doesn’t it?

JH: Absolutely, you’re 100% correct on that.

MD: So what do you do?

JH: I use articulating paper. Usually these patients are paralyzed with muscle relaxants. You can take the chin, click them together and check the occlusion without any problem because the nondepolarizing muscle relaxants like NORCURON® (Organon Pharmaceuticals USA; Roseland, N.J.) make the jaw flaccid. You can click it up and down. But that is a good point. Just like it can be very difficult to check occlusion on someone with anesthesia, it is not easier because they are asleep. I agree, I think it is more difficult.

MD: I’ve noticed on the couple sedation cases that I’ve done, the tongue seems to swell. Is that something that actually happens?

JH: I think it does a little bit, to be honest with you. A lot of times in the office we’ll take full-arch triple trays or quarter-arch triple trays, just for one unit maybe. In the mouth, I’ve had problems with the tongue getting in the way, so we’ve gone almost exclusively to full-arch trays — which ideally is the best way for anything, really; you get all the excursive movements right.

MD: I would assume that on these cases where you go in and do everything, and you don’t know what you’re going to be doing before you walk in, that financial arrangements are a little difficult to do ahead of time.

JH: Here’s how we do that. When we go down there we charge — and my fees are not exorbitant when you hear the numbers — we charge a thousand dollars to go to the OR, and we collect in full a week before the case. Otherwise, you may not get paid. And you know how overhead is. We haven’t had any problems in most cases doing that. Now, if it’s somebody who has tons of stuff or a special patient, say a Down syndrome or cerebral palsy patient, we’ll go in there and do a complete oral exam, periodontal exam, full-mouth X-rays, whatever X-rays we think we need, formulate a treatment plan, do the restorative and maybe do an endo or two. But if they require crown & bridge, we’re probably going to have to come back and do the crown & bridge at a separate appointment.

MD: But their parents or their guardians know that you could go in and they might just need a debridement, or they might need two root canals or four extractions. It’s pretty open-ended, right?

JH: Exactly. For instance, I did a patient with tetralogy of Fallot, which had been repaired. You know, one of the common congenital heart defects. She probably had a mental age of 5. She had a failing pulmonary valve. We took her to the OR, they put her to sleep, and I took full-mouth X-rays on her, then did a full-mouth scaling. I found the supernumerary tooth in the area of #3. So I had an oral surgeon then take her to the operating room and take out the third molars and the supernumerary tooth. That was really all she needed. It was a very simple case. Most of them aren’t that simple. But every now and then you’ll find a patient who may need five surfaces of resin and that’s it. Usually you can’t examine these patients in the office because they’re too combative.

MD: So it sounds like you end up doing perio, too. Is most of it debridement?

JH: Actually, full-mouth scaling and root planing is what we mainly do. I have done perio surgery, but usually if they need perio I’ll send them to a periodontist who sedates patients.

MD: Compared to when you were in private practice, is there more of a premium to work quickly and efficiently with what you do in the hospital?

JH: Absolutely. OR time is very expensive. Let me give an example. There was a guy in Atlanta, just a normal, successful businessman who is an international marble consultant. He had been to one dentist and she tried to work on him, but he had too much of a gag reflex. I’m not sure if she tried to give him some benzodiazepine by mouth or not. But later he was referred to another gal who had taken the DOCS Education course, and she was not able to do anything. So my name came up, and he showed up to the office one day. I said: “You’re a very busy man. Time is a premium for you; time is money. We can go to the OR and do this crown and one two-surface resin and be done with it.” He said, “Do it.” So we did, and then he came back and we put the crown in, in the office.

MD: He was OK with that?

JH: He was fine. The hospital bill for that morning was $15,000.

MD: Hold on, the hospital bill?

JH: That’s the anesthesia and the OR cost. See, the OR is so much for the first hour and then so much for each additional hour, and then there’s the anesthesia charge.

MD: How much did this patient pay between the operating room fee and your fee? How much for the crown?

JH: Well, my fee for the crown was around a grand. Then for the resin, a couple hundred bucks. What we charge is $1,000 to go, plus what we do, with a minimum of $2,000.

MD: So this crown might have cost him $17,000?

JH: His medical insurance I’m sure paid the hospital surgery charge — the operating room charge plus the anesthesia charge that the anesthesiologist bills.

MD: I want you to be proud about this and let people know that you charged $17,000 for a crown! You don’t have to mention that the hospital got $15,000.

JH: Oh God, I would feel bad bragging about that! I would never go out and flash up a pan and say, “I did this in one morning to make 10 G’s.”

MD: I know, I know (laughs). I just think it’s a great story that it cost him $17,000. I guess that goes to show how strong dental phobias can be, huh?

JH: We’ve seen some people who are off the charts! There was one guy I treated 20 years ago, he was about 42, who had severe aortic regurgitation. He was going to have to have a valve pretty soon, plus he was a terrible dental phobic. I couldn’t even examine him in the office. He was sent to me by an oral surgery colleague, who had put him out in the office and taken some teeth out. The patient was missing a number of posterior teeth. I took him to the OR and we got into a pre-op hold area, and he would not let the anesthesia provider start the IV. I came up and I said: “I’m going to give you one chance, my friend. You let this professional put that IV in or we are done.” And he shut up and let the guy put it in. Sometimes you have to take that approach.

Here’s another thing. You can also give them Ketamine, which you’ve probably heard of, in the thigh. It’s a dissociative anesthetic, and what you do is put 50–100 mg in the big muscle of the thigh and they’ll go out immediately. Then you can start the IV. We did that with the brain tumor patient. We had to take her to a special room off the pre-op hold area, where we had two anesthesiologists, myself and a couple of nurses; the parents were in there, too. We gave her a shot in the thigh and out she went.

MD: So with the guy who was refusing the IV in the arm, are you saying that to give it in the thigh is easier because you just slam it in there rather than having to finesse with the IV?

JH: It would have been easier if they had given him ketamine. That is probably what I would have recommended if he wouldn’t let them start the IV right off. They do that with many kids for surgery because ketamine will put them out.

MD: But not orally?

JH: No, not orally; it’s given intramuscularly. It can be given in an IV. I used it when I was a resident for trauma anesthesia many years ago in Chicago. Typically, say you have a 70 kg patient, an adult. You can give them 50–100 mg in the thigh and that will put them out enough to allow you to breathe them down by mask with the inhalant anesthetic — the anesthesiologist is doing this, of course — or start the IV and give them something like propofol.

MD: So $17,000 crowns notwithstanding, when you go in and do these cases, can you have a fairly productive day?

JH: Oh, yeah. You can have a good day — absolutely.

MD: Do you find yourself more productive in this type of setting than when you were in private practice?

JH: Actually, it depends on what you do. There was one case we did on a child who had developmental delay. I’ve treated her a number of times in the OR, and one morning I think we produced $8,000 in the OR. That’s a big day, though. You normally don’t produce that much. If you do three or four crowns, you’re looking at $4,000 plus $1,000 to go down there, so that’s $5,000. But you don’t do that every day. Typically, these patients have not had incremental care for a while, so there will be endo for obvious reasons, some restorative, some crowns. We like to see if we can get X-rays from another source or even our own office before we go down there, so we know what we’re going to be doing. So it depends on what you’re doing exactly. If you’re doing a couple of endos, two or three crowns and a bunch of restorative, you can have a multi-thousand-dollar morning without any problem. Of course, you can do that in the office, too.

MD: Well, it sounds like the average case in the OR might be bigger than the average case in general dentistry.

JH: Probably so. I’ve been told by oral surgeons that I need to charge more, but as you well know, that’s all relative. I have a pedodontist friend who has a big practice here in Atlanta and he grosses between $1.5 and $2 million. Half of that is ortho. He had a three-year program in Connecticut where he had a year of ortho. He is the exception to the rule. He does a lot of hospital dentistry on very sick kids. He sedates in the office also. I think his minimum is $2,500 now to go to the OR. He goes only on Fridays. Friday is his OR day. Now, obviously, that kind of production is not typical.

MD: Right. If there is somebody reading this who says: “You know what? That sounds like fun. I’d like to be able to help out developmentally disabled people. I like the idea of being in a hospital or doing some of these cases.” Or maybe they’re drawn to the excitement of not knowing what they’re going to be getting into. How can somebody get involved?

JH: It is enjoyable, it really is. Emory University Hospital requires a residency of some type to be on staff. Typically, dentists who do hospital dentistry have had a GPR. A smaller community hospital might allow you to come in and watch and get on staff without a residency of some type. But at Emory, and probably at USC, UCLA and all the other centers out there, they usually require a residency of some type — whether perio, GPR or pedo. Obviously all the oral surgeons go to the OR. The reason for that is that they do not want to teach you how to work in a hospital. They want you to know already how to work in a hospital environment. There is a lot of paperwork involved.

MD: Not only that, but it sounds like if you are not used to working in a hospital, you’re probably not going to bring as much stuff with you to the hospital as you need. I could see it being a real mess.

JH: We’ve got a two-page list for the basic setup. We’ve got a list for endo. Then we’ve got a list for crown & bridge. So my assistant takes that list and packs the chest and the bag. I usually get there at 5:30 in the morning for a 7:30 case. I get everything set up and laid out and ready to go. We have an A-dec® dental unit (A-dec Inc.; Newberg, Ore.) and an Air Techniques PA machine that the hospital bought for me. I get that hooked up and get the sterile water in the water canister, get the waste canister screwed on and check all the lines. I have every nut and bolt ready to go. They like me when I come because I’m never late, and they never have to go get anything. All we do is work.

MD: Do they have people scheduled after you in that OR?

JH: Probably so. There are probably 30 ORs in the main OR. It’s a big, new 20-story hospital. I always get my cases scheduled first thing, and I tell them I’m going to be going until 1 or 2 p.m. maybe, so I need the OR blocked off. But there may be a case after me, maybe a general surgery. You never know what room you’re going to get stuck in, either. I usually go the night before to the OR, before I leave work, to make sure that the X-ray machine is there, that it’s not off somewhere else in the hospital, and that the dental unit is ready and working.

MD: I would assume that it is pretty bad etiquette and that it would make them pretty unhappy if you ran three hours late, right?

JH: Oh, good lord. Some of these general surgeons will come in there 30 minutes late. But general surgeons have a general surgery pack. All they do is waltz in and they open up the general surgery pack and start whacking.

But for dentistry, you’ve got to have your dental unit set up. You’ve got to have it plugged into the medical nitrogen, and you’ve got to have your X-ray stuff all laid out. I carry a Hewlett-Packard laptop with a Gendex® digital intraoral sensor (Gendex Dental Systems; Hatfield, Pa.), and I use VixWin™ PRO software (Gendex Dental Systems). It works great.

MD: We’re both lecturing at the next CDA meeting. Is this the type of thing that you’re going to talk about in your program?

JH: I am. The title of it is “29 Years of Dental Anesthesiology in Hospital Dentistry.” It’s going to be about special patient care, whether in the office or in the operating room. I’ll be giving a little blip on my training — I’ve got slides that go back 30 years. We’re going to have some information on where I trained and what the training program was like. Then we’ll move into anesthesia in the dental office and then into hospital dentistry. I’ve got a bunch of cases, which seems to be what people like to see, the final product. I could talk all day, but it’s going be crammed into an hour and a half. It’s 278 Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Wash.) slides.

MD: Wow, that sounds like an action-packed one! I can tell just by talking to you for this short time that you’ve got thousands of stories — and all of them entertaining.

JH: We’ve had a lot of fun, we really have. The people at the hospital are very good to me. When I go down there I treat every nurse and every tech with the utmost respect. I don’t throw stuff at them. I don’t holler at them. You’d really be surprised how much they’re willing to work for you when you treat them like that. I’ve got a lot of them from the OR as patients.

MD: Of course. But you treat them in your office, right?

JH: Absolutely, a lot of them.

MD: They probably don’t want to be seen in the OR.

JH: Exactly! (laughs)

Dr. John Harden practices in Atlanta, Georgia, and is on the medical staff at Emory University Hospital Midtown. Contact him at jhdmd@bellsouth.net or visit jhdmd.com.