Digital Communication of Critical Cosmetic Restorative Guidelines

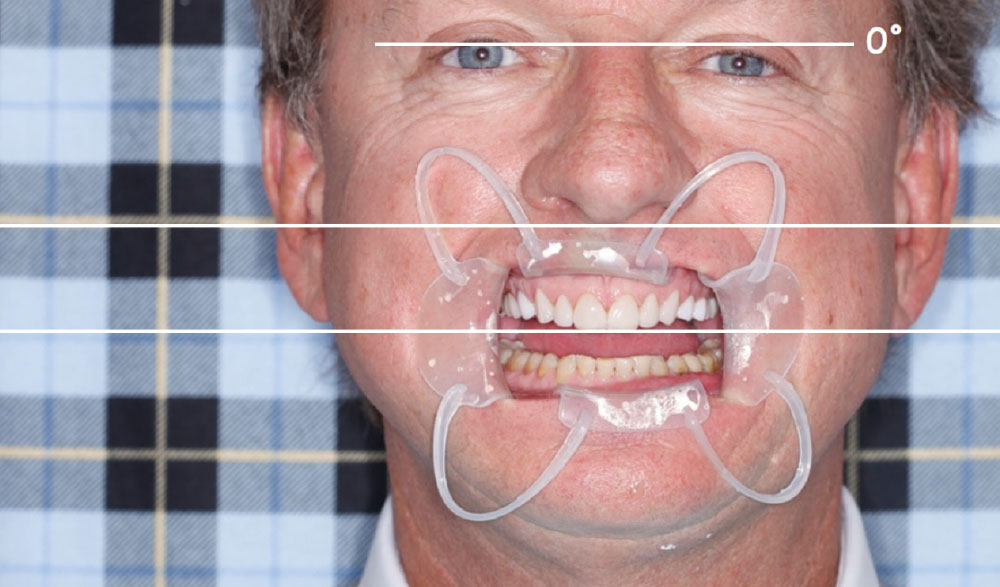

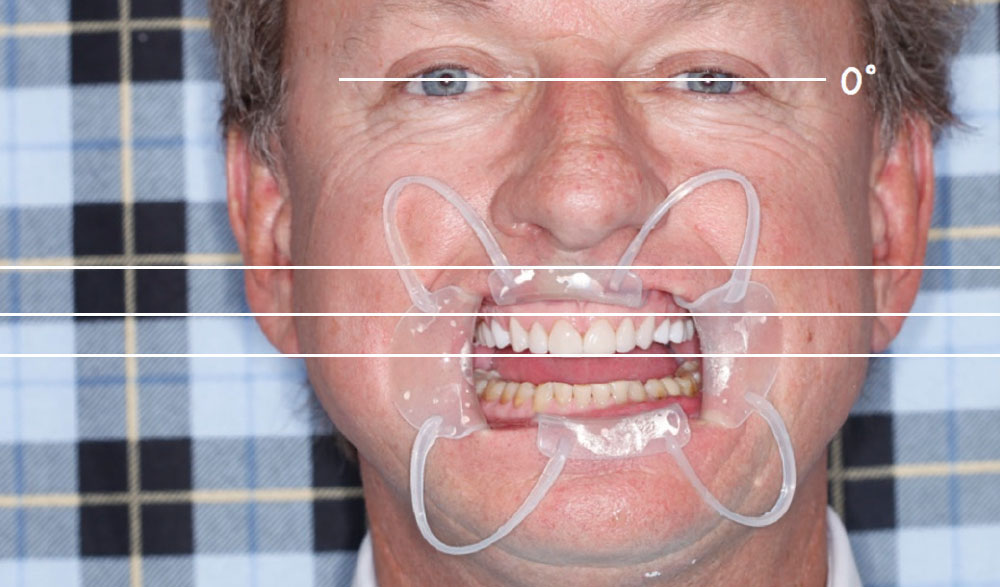

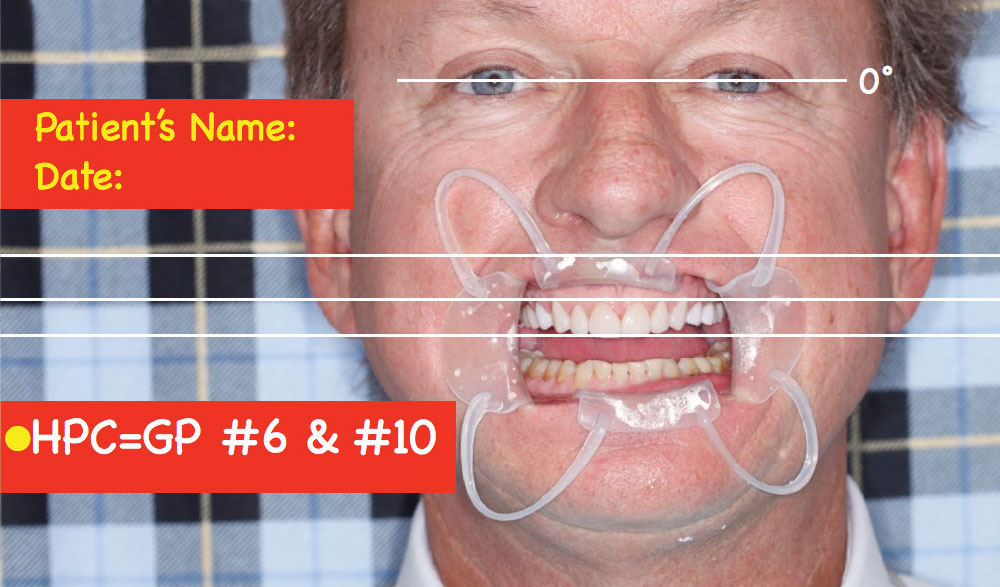

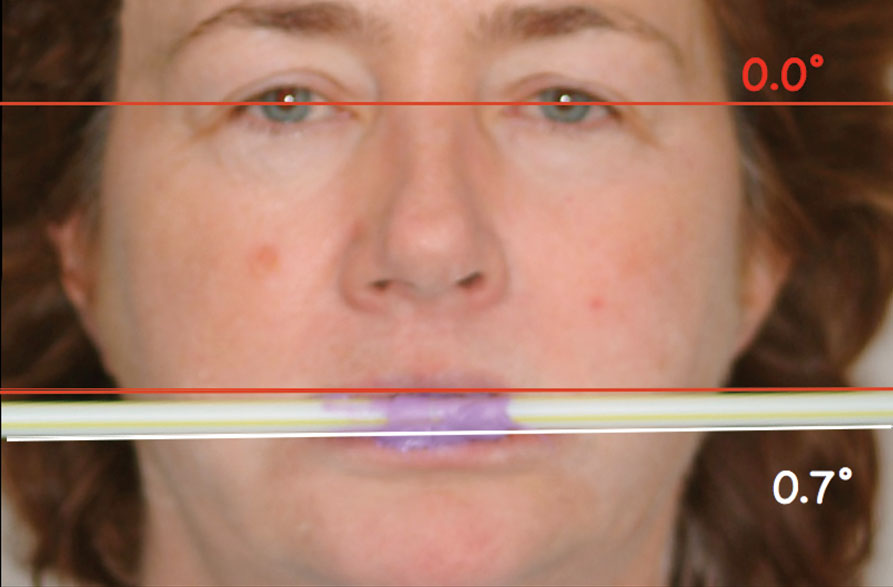

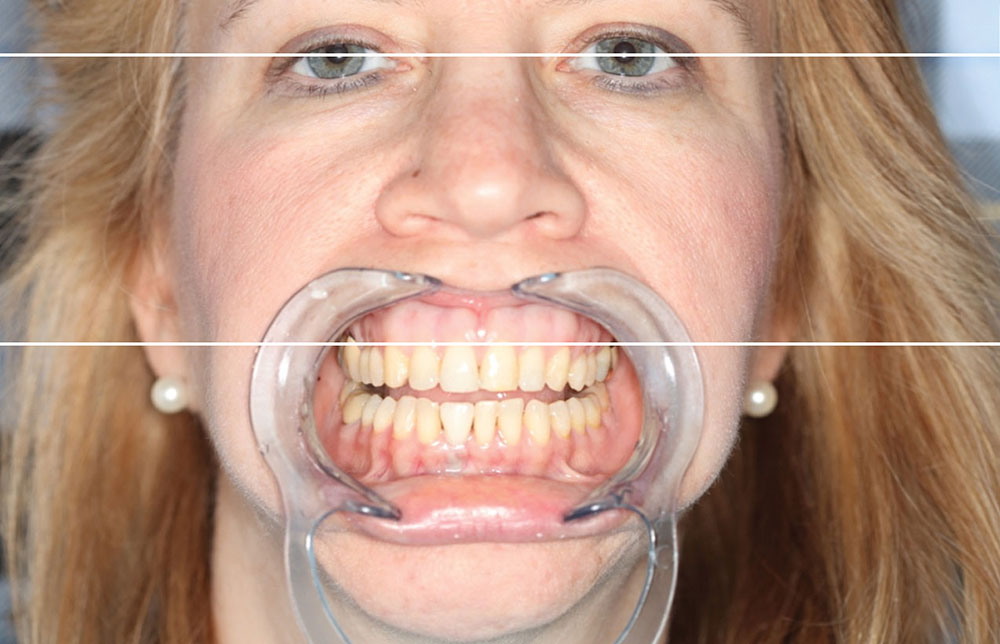

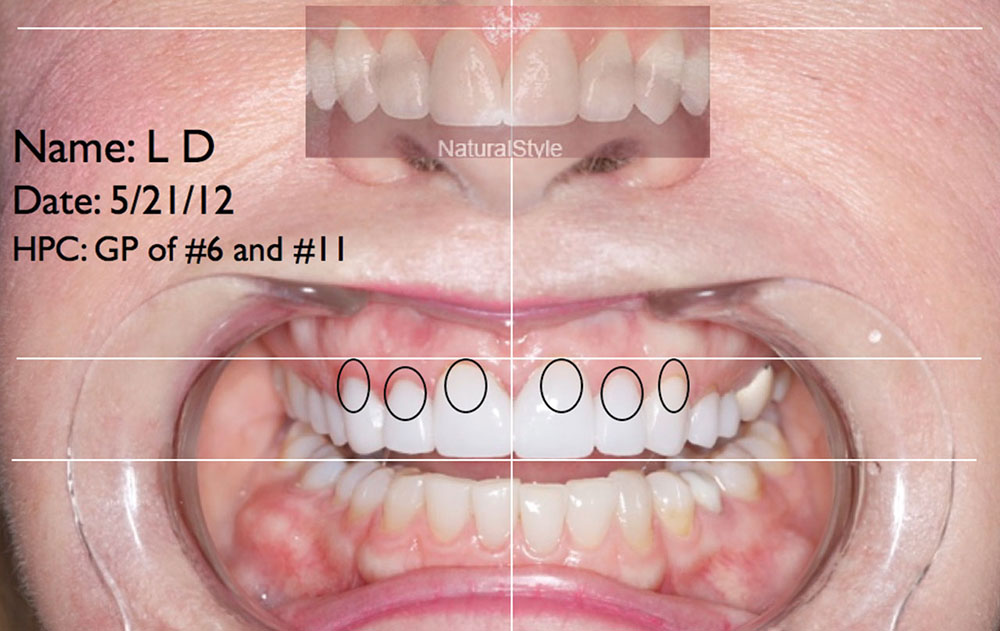

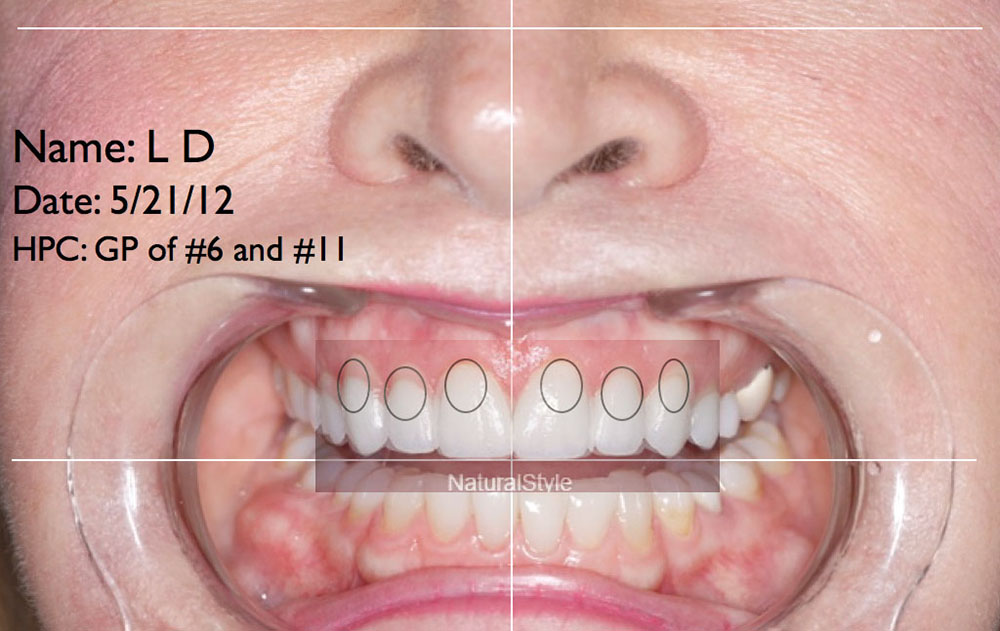

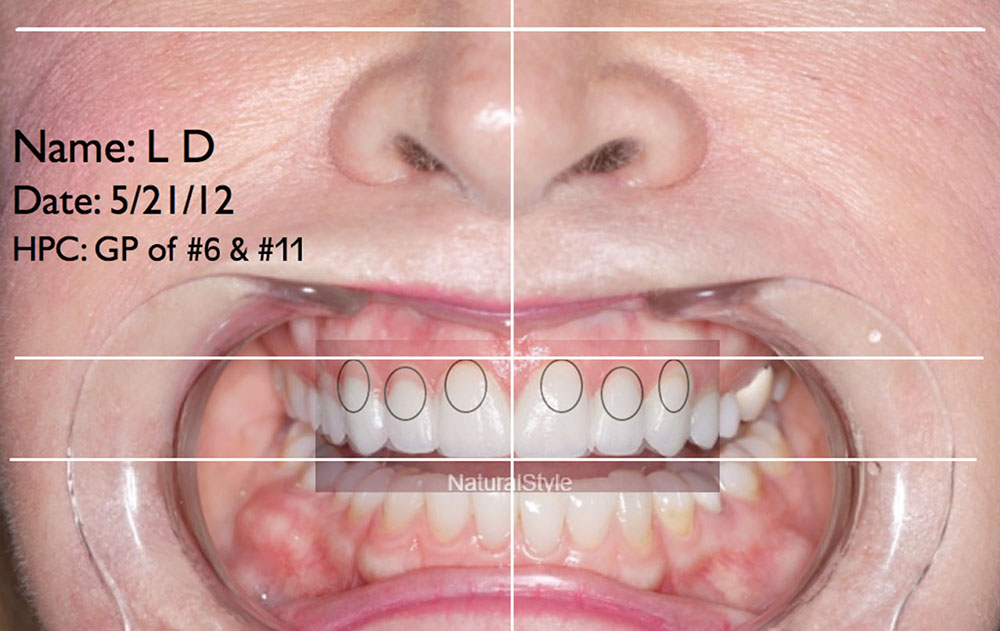

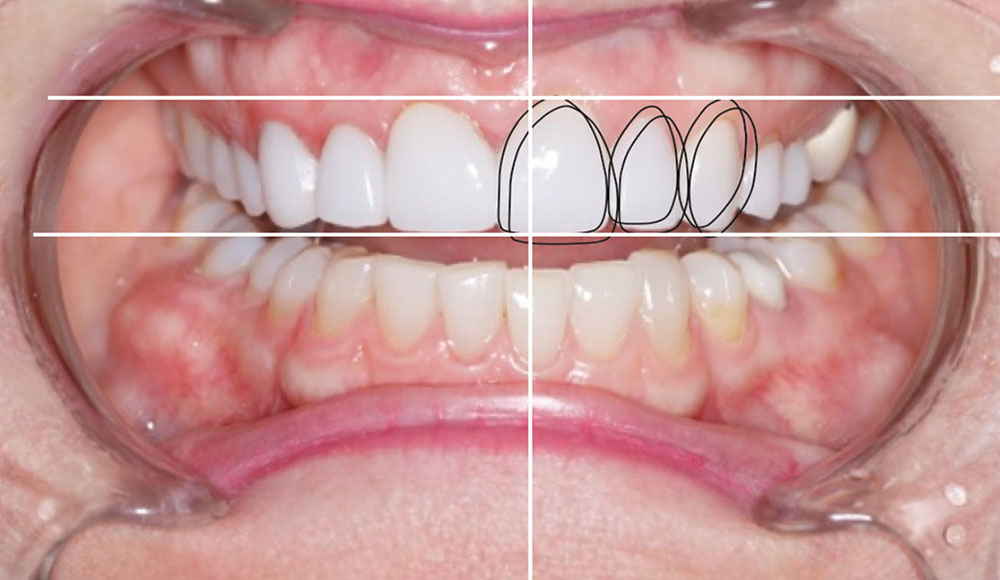

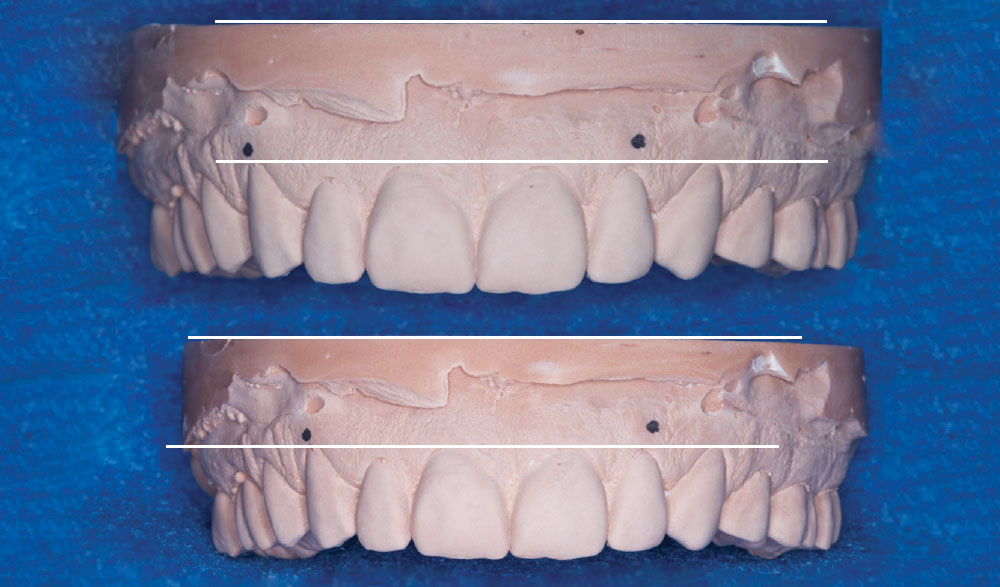

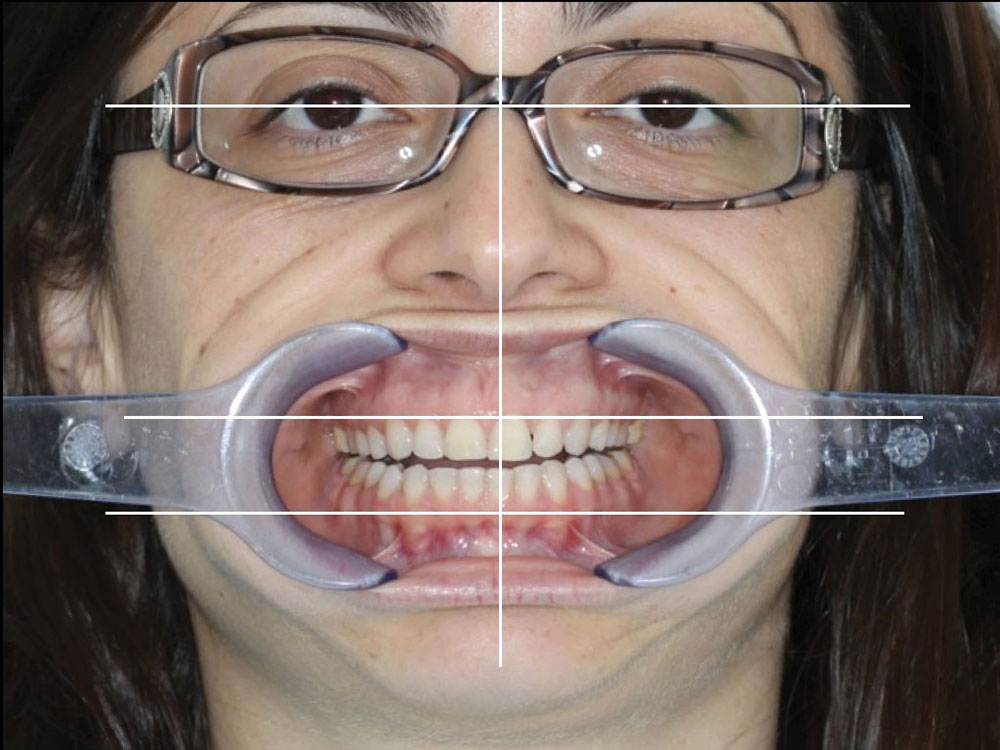

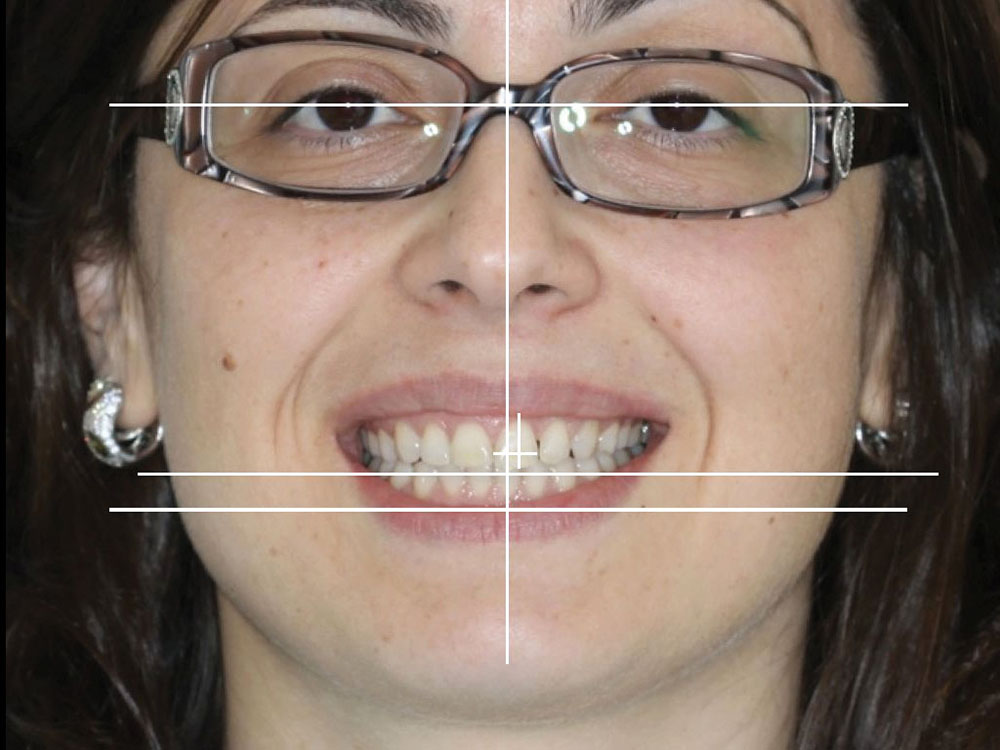

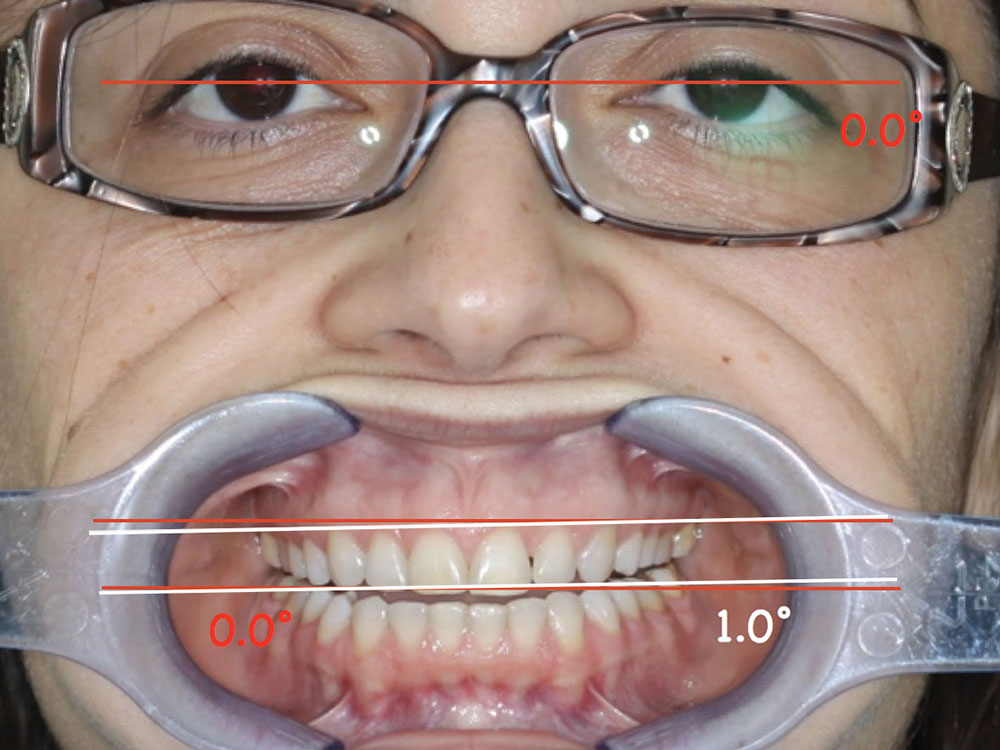

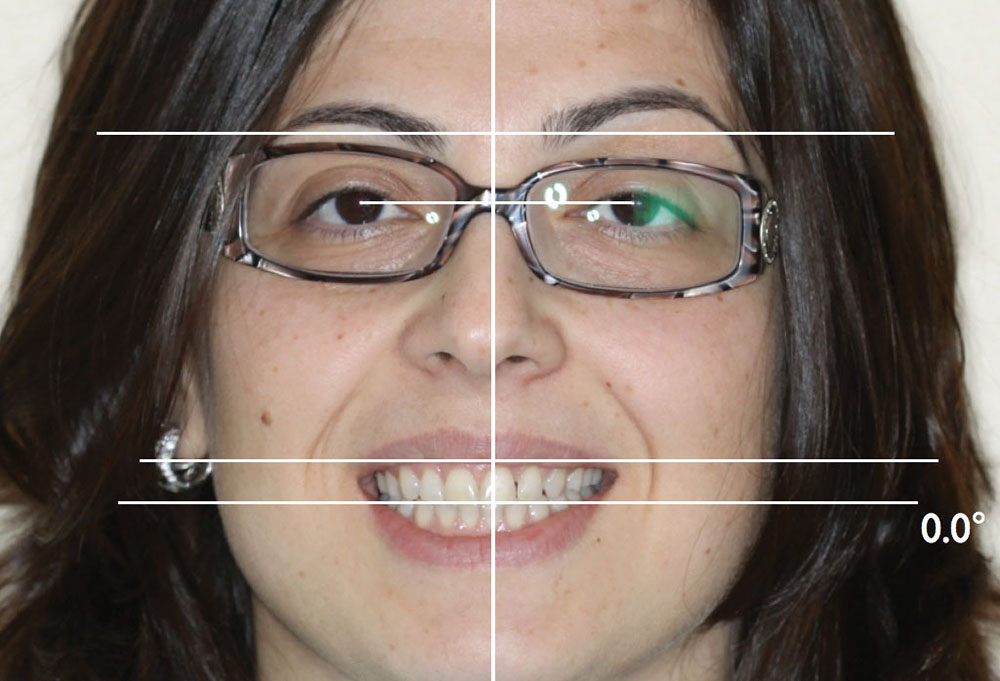

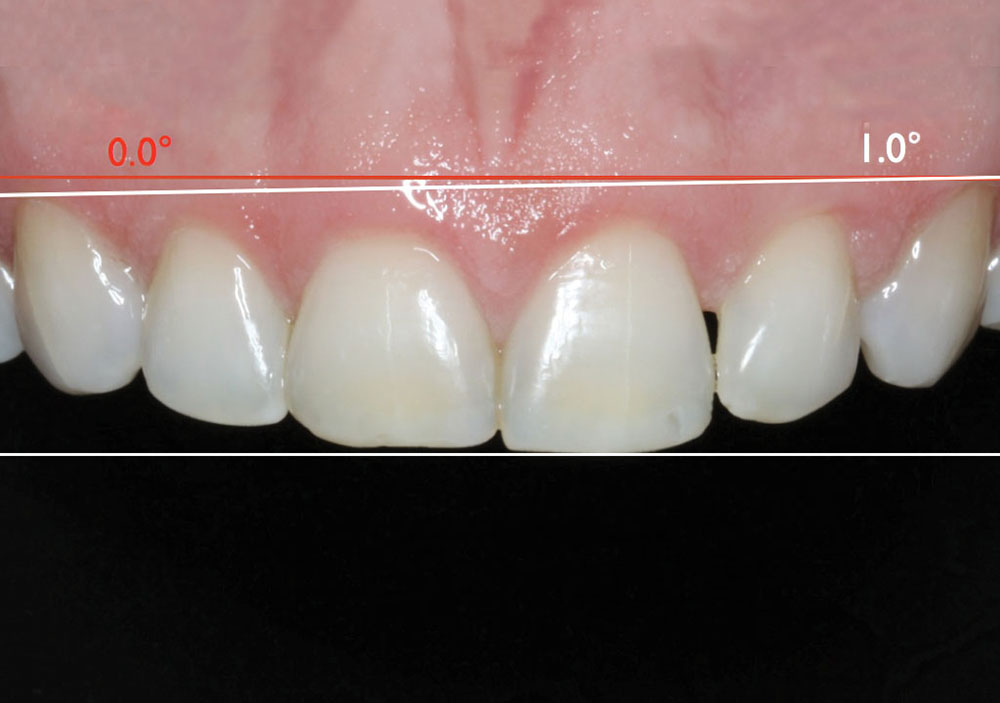

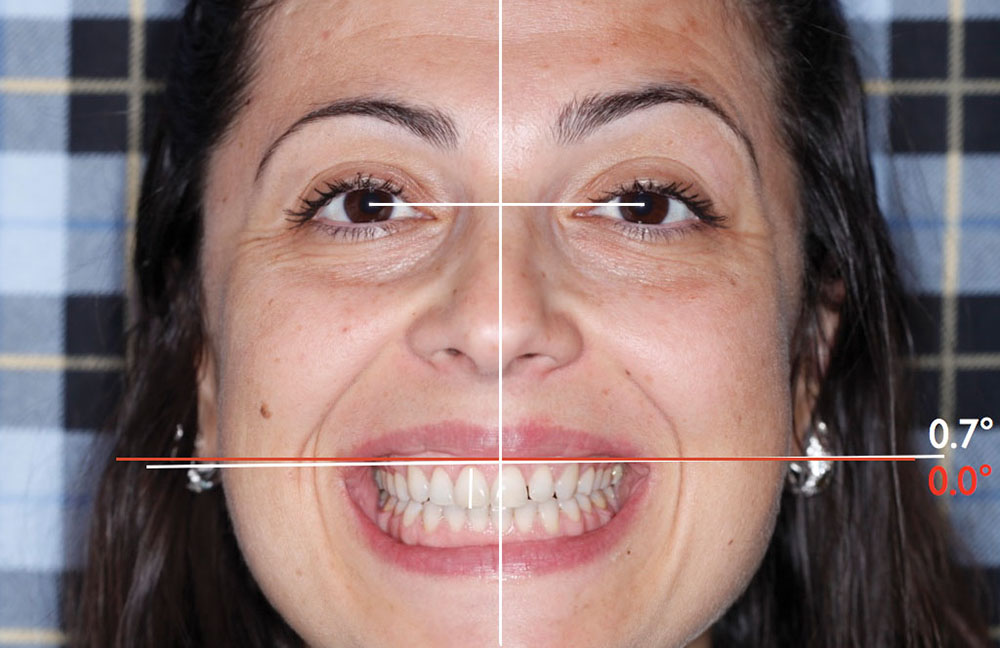

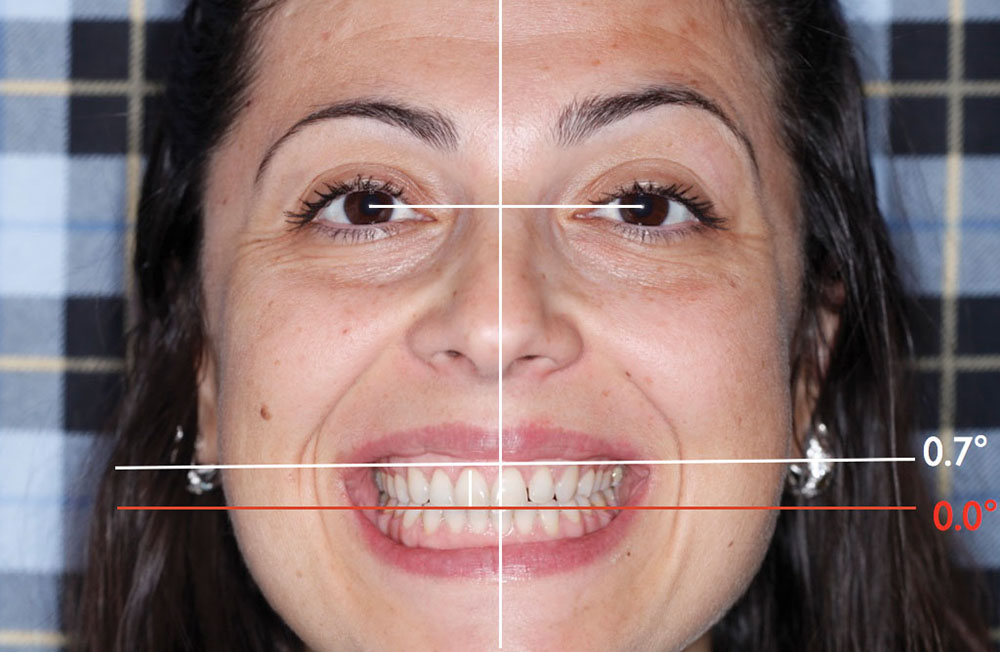

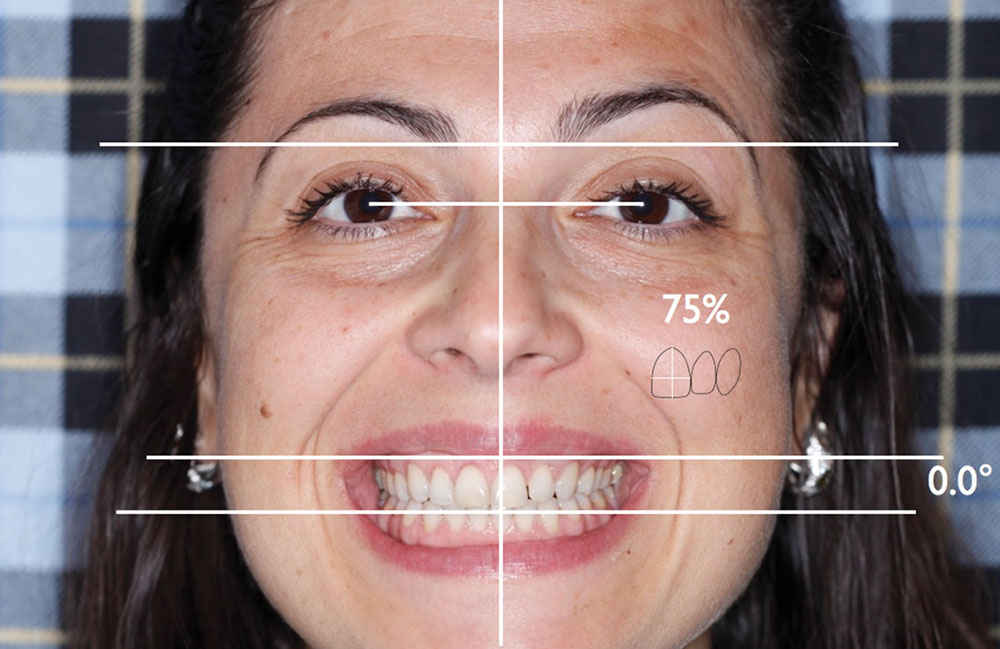

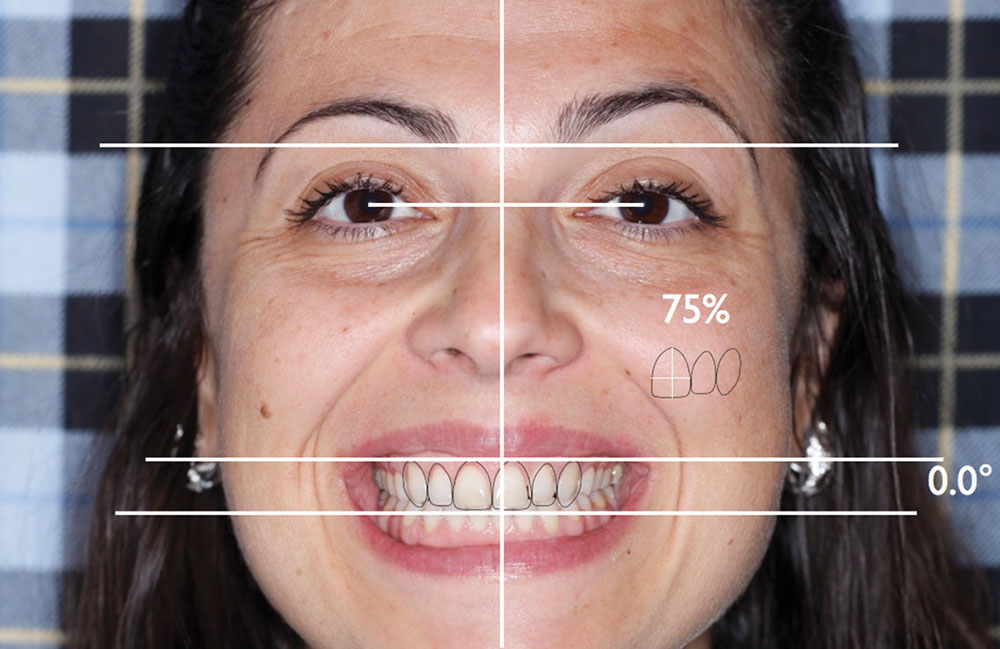

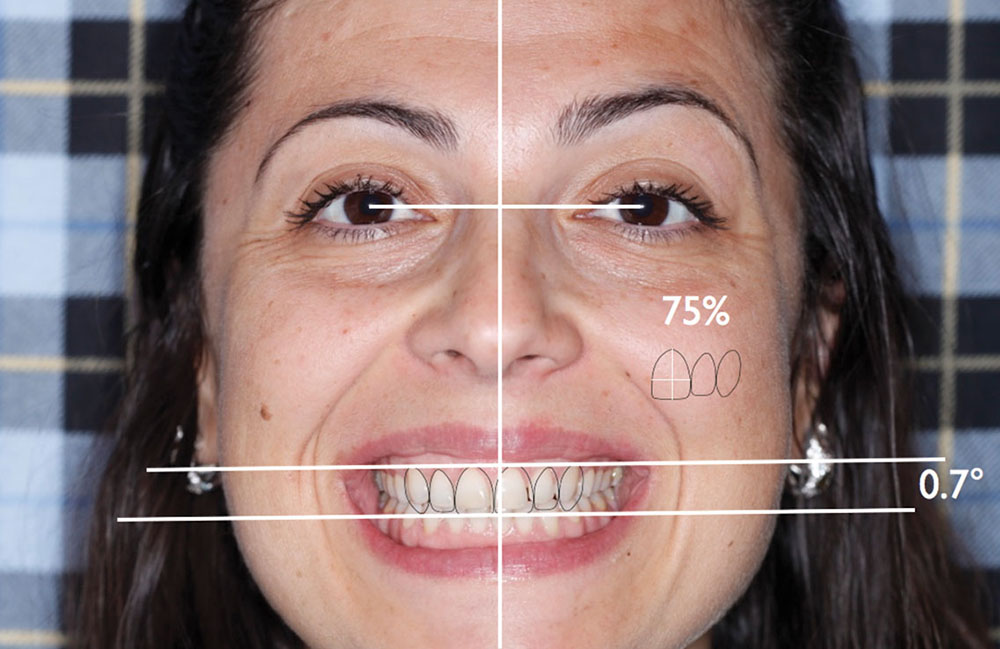

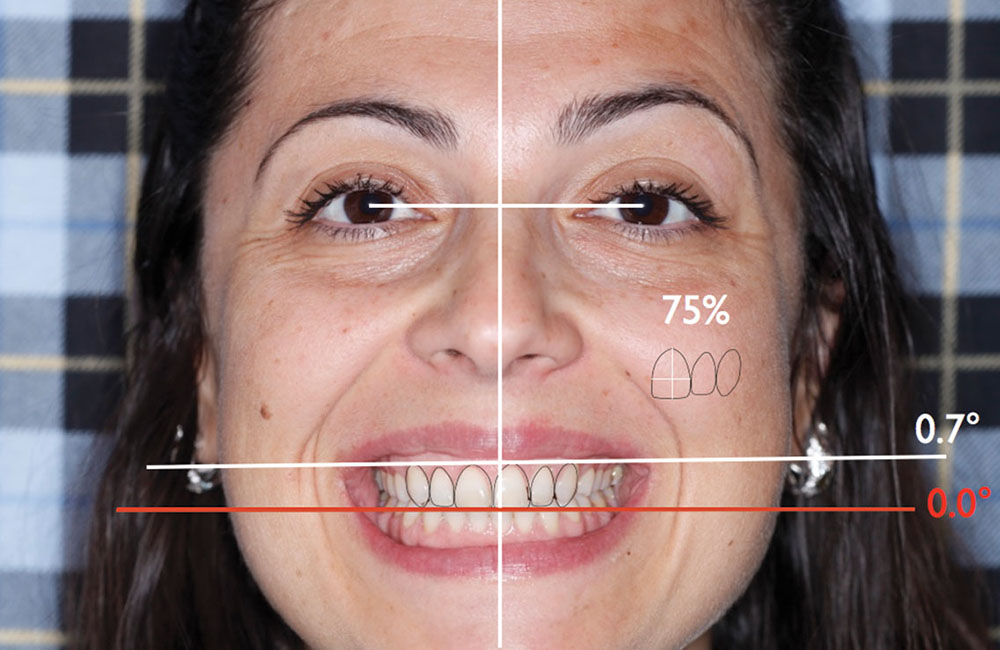

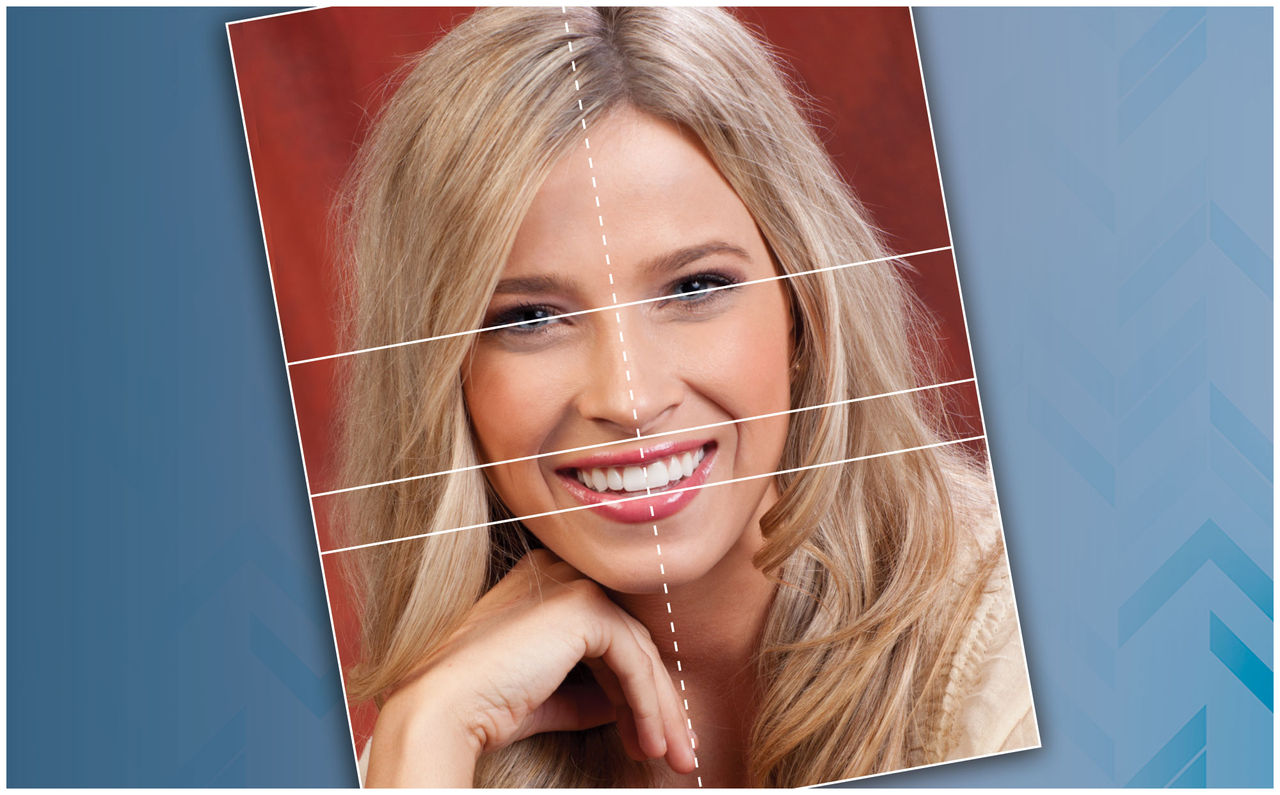

One of the most important elements of a cosmetic restorative case is the horizontal plane of the case (HPC). The HPC is defined as the plane that the incisal edges of the anterior restorations should follow relative to specific landmarks of the face. Ninety percent of the time, the plane can follow the pupillary line plane. The gingival plane of the anterior teeth should parallel the HPC when the gingival line is visible in the smile. Facial asymmetry and biological limitations based on anatomy dictate the reality of what is possible when matching the gingival plane to the chosen HPC.

Leaving the HPC up to chance or ignoring it often compromises the cosmetic outcome of the case. As such, it is important for the restorative dentist to define and then communicate the HPC to the laboratory and to the specialists involved in the interdisciplinary treatment of the case. When biological limitations do not exist, it is important for the laboratory and the specialists to follow the designated plane.

Analyzing and deciding on the appropriate HPC is easily done using a lip-retracted, full-face digital photograph imported into presentation software such as Apple Keynote® (Apple Inc.; Cupertino, Calif.) or Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Wash.). In this author’s opinion, Keynote is by far the easiest program to use.

Steps in the Digital Communication Process:

1. Take the photographs.

2. Analyze the photographs to determine the HPC.

3. Communicate the HPC to the laboratory and the specialists involved in the interdisciplinary management of the case.

Diagnostic waxing, case planning and finishing using an incorrect HPC is a sure way to compromise the cosmetic outcome of the case.

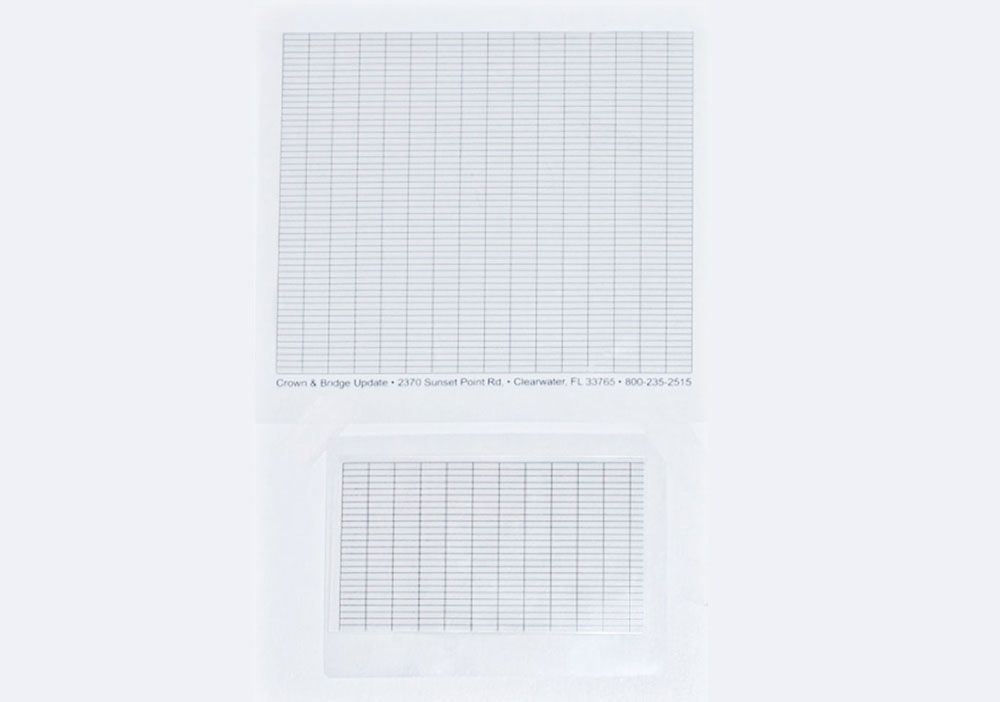

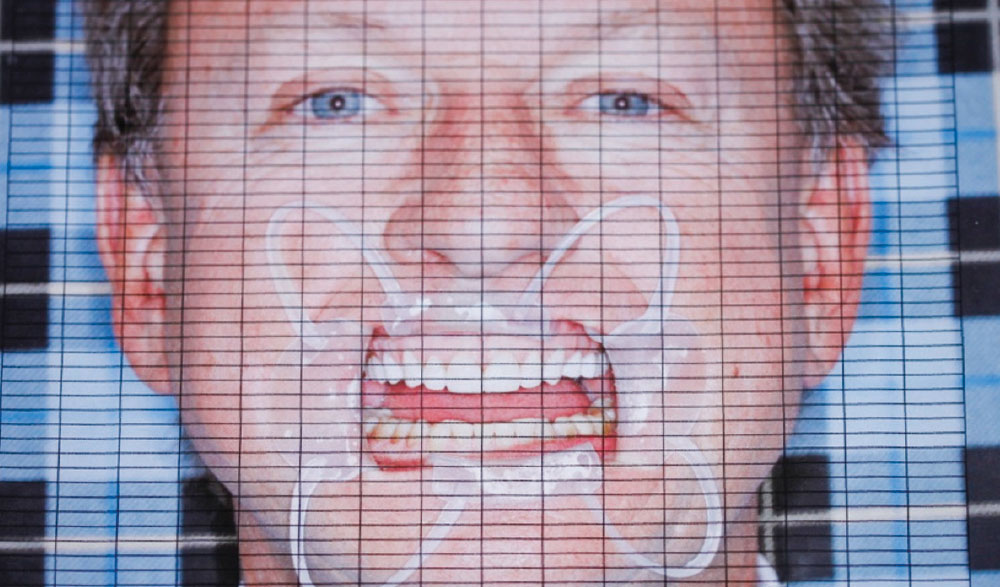

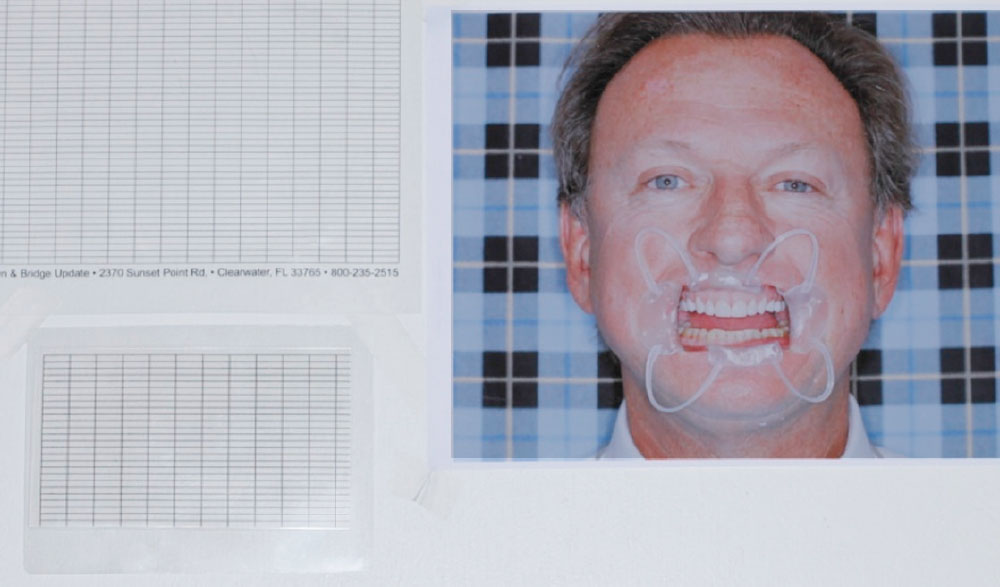

Most of the communication needed can be transmitted with the use of a Straight Smile Guide. Created for technophobe dentists, it is a quick way to analyze and communicate critical cosmetic parameters to the team.

Dr. Bill Strupp practices in Clearwater, Florida, and lectures internationally on the subject of comprehensive cosmetic and restorative dentistry. He also publishes “Crown & Bridge UPDATE,” aimed at educating dentists in better dentistry. Contact him at 800-235-2515 or bill@strupp.com, or by visiting strupp.com.