Clinician Spotlight: Occlusal Splints

Dr. Michael DiTolla recently sat down with Dr. Anton Misleh, one of Glidewell Laboratories’ top customers for occlusal splints and a dental school classmate of Dr. DiTolla. Dr. Misleh shares his thoughts on the importance of bite splints and how he includes their use in his practice.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: Good morning, Anton. We’re going to talk a little bit about splints. I’ve always liked occlusal splints. I think it’s one of the most conservative things we do. You are one of our most active doctors regularly doing splints, and I wanted to ask you a few questions. Let’s talk about what you learned about TMD and splints when you attended University of the Pacific School of Dentistry.

Dr. Anton Misleh: Well, that’s simple — not a lot. But I’ll be honest — I didn’t pay a lot of attention to it. It was kind of boring to me at the time. The information, I’m sure, was there, but I didn’t give it the attention it needed. When I got out in my practice, I started seeing a lot of busted up teeth, traumatic occlusion, and had to start thinking about occlusion. So after taking a lot of classes, I became more familiar with it. And, of course, after finally starting to do a thorough TMD exam instead of a cursory one, I started taking it really seriously. That’s the key — a thorough TMD exam. When you start looking for it, you start finding it. It’s amazing how many people have TMD-type issues: soreness, headaches — you name it. Stuff they never really attributed to their jaw until you explain to them why their neck hurts, why their jaw hurts. It’s amazing — you can get really quick, instant results with a splint. Then they come back and thank you for it.

MD: So when you finished these classes and came back to your practice and started presenting these concepts to your patients, did you meet with a lot of resistance from patients?

AM: The majority of patients would tell me that they do not grind their teeth, yet I could look at their mouths and see this obviously wasn’t the case. What helped me was to say, “Let me take an impression and I will pour up some models to show you, since it’s too hard for you to see in your mouth.” I gave up on the intraoral camera a long time ago. I have one in the closet with a bag on it. But the interesting thing was, I’d show them on the models where the wear was, how their teeth fit together, and once they saw that, I would ask them: “Where could this wear be coming from if you’re not grinding your teeth? It’s got to be coming from somewhere.” And the answer is, you’re mouth breathing part of the night, you’re grinding part of the night, you’re sleeping on your right, you’re sleeping on your left — you’re moving. If we took a video of you while you’re sleeping, you’d be amazed how much activity you get from all of your muscles while you’re asleep.

MD: So patients begin to accept that they are grinding their teeth?

AM: Yes, but you know what the next question is: “Why am I grinding?” Because everyone grinds. I tell them, you’re grinding, your parents ground, their parents ground. Unfortunately, it’s a very stressful life we live in. It’s pleasurable in some instances but stressful at the same time. We just have to understand that. We have to do something. The only thing we can do — you’re never going to stop grinding, you can’t stop grinding, I don’t know of a way to make anyone stop grinding — but the one thing we can do is, if we put a piece of plastic between your teeth, you’ll damage plastic and quit damaging yourself. I like to speak to my patients in very simple, very basic terms. I’m not into scientific conversations with people because, let’s face it, this is an abstract concept that we’re not too familiar with. And that’s what we look for: worn teeth, popping of cusps tips, abfractions and recession. Recession is more important than we think. Most dentists will just bond mesiofacial distal composites on receded areas and tell the patients, “Oh, you’re brushing too hard.” To be honest with you, and I don’t mean to criticize anybody, but I don’t believe anybody is brushing too hard. I think it’s the abfractions and the recessions caused from occlusal trauma such as bruxism that exposes the softer part of the root, and then you brush away tooth structure. I really think it’s the traumatic occlusion that starts the whole process.

MD: I would agree. In fact, when I heard about toothbrush abrasion in school and people brushing too hard and even patients saying, “Oh, I’ve been told that I brush too hard,” I always found it amazing that they were able to brush too hard on a first bicuspid but they weren’t brushing too hard on the adjacent cuspid or the second bicuspid. The only way to explain it is if they had like a 3 mm wide toothbrush and they just constantly brushed that one tooth.

AM: You know what? You just hit the nail on the head. Very good example.

MD: It just doesn’t make sense — if they’re brushing too hard, why do I see it in only one area, and why does that happen to be the area that has a lateral occlusal interference at the same time?

AM: You got it.

MD: Explain to me a little bit what you do — it sounds like you’re pretty comprehensive in looking for TMD symptoms and bruxism symptoms in all your patients. Can you explain how you work it into the new patient exam?

AM: Every new patient, standard exam. They come in, they get their FMX, we probe, we do cancer screening — I’m very big on that, too — we have actually discovered some cancer cases while it was still early. Then we do the TMD exam. We start with just asking them about their jaw joints, headaches, any symptom in their neck, back of the head, radiating up to their head, then I palpate the muscles of mastication. Invariably, there’s always a little tenderness on one of the lateral pterygoids or on the medial pterygoid. That’s a tough one to palpate — some people think you can’t, but they have a little tenderness there as well. When you see the occlusal wear and document it — and we do document the recession — where the abfractions are, and once you see all that coupled with their personal history about their pains, their sensations that they feel (if they wake up in the morning and their jaw is tight, etc.), they’ll tell you all kinds of things in their words that mean something to us. You have to listen to them, as well as look at them. After we do that part of the exam, we give them a head and neck screening as well — we palpate from the neck up. We were very successful in finding thyroid disorders on many patients already — which dentists usually don’t look for. And I’ll be honest with you — we don’t have time in our day, but we make the time. It’s amazing how many physicians have called me and said: “I can’t believe you guys found that. Good job.”

MD: That’s a great point. That’s an incredible service as a dentist for you to be providing. Now, do you find any benefit in devices to help diagnose TMD problems? For example, a JVA (Joint Vibration Analysis) device is advocated by some clinicians.

AM: Well, I’ll be honest with you — I don’t use any of those devices. I’m strictly looking for trauma to the dentition, to the gingiva, and when I palpate the muscles and take the patient’s history. It’s not that I don’t believe in those machines, but other than seeing them on a slide at a lecture, I’ve never touched one. I learned one main thing as a result of all the TMD courses I took: Refer out all TMD. It’s not something I want to treat on a complicated basis. The simple things that require a splint, the patients that a nightguard will help, I treat them. Anyone that requires a more extensive diagnosis, more extensive treating such as an anatomical splint, which gets into a whole other area of splints — we have a wonderful TMD specialist in the building who just moved in. Prior to that, I was using a few others nearby. Now I refer my cases to him and he has all those machines, and he enjoys treating those patients.

MD: Do you err on the cautious side if you have somebody who might be a more complicated TMD patient in referring them to the specialist, or are you gaining enough experience now where you’re more willing to try to treat those people in your office?

AM: I’m gaining more experience to err more on the cautious side. When I didn’t have enough knowledge in the matter, I think I probably erred too much on the “treat it” side. As you learn more and more, you learn to be more cautious, and you learn to more judiciously think about what you’re treating and how you’re going to treat it and why.

MD: It’s funny because I ask many dentists, “Why don’t you provide more splints in your practice?” A lot will say that TMD patients are crazy or they say you end up being married to those patients. Yet, you still do many splints despite referring out the TMD patients.

AM: I’m doing a ton of splints because here’s my philosophy on splints, and this is important to know: I’m doing the splints to prevent the wear to the dentition. I’m not doing the splints so much to treat the TMD. That’s key, because if they have true TMD, you’re right, you’re married to the patient. And, you know, different guys charge different amounts for these splints. I charge $450. I don’t know where that stands in the range, but the point is, you don’t want to be married to the patient for $450. But the interesting thing about it is, if you get proficient at properly diagnosing these TMD issues and properly referring them out like you’re supposed to, the specialists are very good at charging a much higher fee and they are very happy to be married to the patient.

MD: Well, we talked about new patients — can we talk about recall patients? Let’s say there’s a patient who’s been in your practice seven or eight years, and maybe you weren’t treating TMD as thoroughly or as aggressively as when they first came into the practice, and now you know more and they’re in with the hygienist. Typically, with these recall patients, is this something your hygienists bring up, or do they bring it to your attention and you start the conversation? How do you go about communicating treatment to patients who have this problem?

The most resistance I get to the concept of telling someone that they’re bruxing their teeth is, “How come I was never told this before?”

AM: Classic question. My hygienists dive right in. They’re on the TMD bandwagon. My hygienists — if they just did hygiene, they’d be bored. They like trying new things and looking at new things. It just makes their day more exciting. Something you touched on earlier, you just touched on it again — you talked about the resistance to this whole concept of bruxism. Where the most resistance is, the most resistance I get to the concept of telling someone that they’re bruxing their teeth is: “How come I was never told this before? I’ve been coming here for years. How come now?” That could be a very awkward situation. I’ll be honest with you — when I first started recognizing malocclusion and traumatic occlusion and the wear, and first started bringing this up to patients, that presented a big problem for me. You find yourself having to backpedal, and you say, “Uh, uh, uh ….” And you don’t want to say, “Because I completely ignored it for the last 18 years.” In reality, we do ignore it. It’s probably one of the most ignored aspects of dentistry. So I just told them, “I’ll be honest with you — I’ve been doing some studying on this, and I’ve become more and more aware about this, and you’re being told now because I know more about it now and that’s that.” I was very surprised how quickly I gained acceptance because it’s a very truthful and straightforward answer, and it doesn’t scream of incompetence that it was not recognized before, but it’s very truthful. That is exactly the way we present it. We gained great acceptance with that. It’s a new concept for them, just like it’s a new concept for us — it’s not supposed to be, but frankly we can’t learn everything in one night. I wish we could, but we can’t. So this is just one more tool we’re adding. Why did you break your tooth? Well, before we would’ve just fixed the tooth. Now we’re finding out why so you don’t break it again and so you don’t break others. So I tell them to be grateful that we finally figured this one out.

Mom never told us, “Don’t get TMD.” So it’s really important to make ourselves aware of it, educate ourselves about it. Once we do, then we can educate our patients about it.

MD: Exactly. And there is no dental condition that I’ve seen where a patient can have so much denial — maybe with periodontal disease there’s some denial, too. But the patient denial that goes along with bruxism is amazing.

AM: Like I touched on earlier, it’s a new concept for the patient. When we tell them, “You have a cavity, you need a filling.” Well, everyone has had a cavity, everyone has had a filling, they’re going to keep getting them. It’s such an old concept, there’s no need to accept it — it’s just already been accepted that we get cavities. And there’s a lot of advertisement to it. You know, you just turn on the TV and Crest is advertising, “We’ll help you prevent cavities.” And Colgate is doing the same, and so cavities have always been addressed in the media, in advertising, everywhere. And our mother told us to brush our teeth so we don’t get a cavity. So it became a very important concept early on. But Mom never told us, “Don’t get TMD.” So it’s really important to make ourselves aware of it, educate ourselves about it. Once we do, then we can educate our patients about it. And they’re starting to learn. They’re starting to accept TMD. You know, as I started becoming more aware of TMD, I started noticing more articles in the paper about it and in magazines. I never noticed it before when you read the papers or magazines because it wasn’t there.

MD: I love giving those types of things to the patients. In fact, I’d rather give something like that to a patient than one of those preprinted dental brochures marketing some product you can buy. I love when it’s in a neutral, third-party press. If you find something in San Diego Magazine or the Union-Tribune and you can give that to a patient, written by an outside reporter, I think that almost carries more credibility than a pamphlet our office can print up and hand to a patient.

AM: You’re 100% right. We maintain good relationships with our patients — we’ve always enjoyed good relationships, a trust. Dentistry is still one of the highly trusted professions. But unfortunately, in society, just in our minds, in everyone’s minds, there’s still that element of distrust. So you bring in something that is trusted — like you said, San Diego Magazine. They make good restaurant recommendations — why wouldn’t they talk about TMD properly? So then it creates more trust, and it’s in a medium the patient has long experienced trust with.

MD: And the reason you need more trust with your patient, I think, to treat something like bruxism and make a splint for them is because it is, by and large, a painless condition. When a patient comes in pain with an abscess, or they’ve broken a cusp off and it’s shredding the side of their tongue, they are ready to have that thorn pulled out of their foot. But when it’s an asymptomatic — to them — condition, they need to have some trust that you are in fact treating something that does need to be treated.

AM: Seeing is believing.

MD: What types of splints do you use in your practice now? Is there a particular one that you’re using in your practice as kind of your go-to splint?

AM: I’ve settled on your splint, actually — the Comfort H/S™. For the most part, the Hard/Soft goes in really simple, really easy, doesn’t take a lot of thinking. There’s a little bit of adjustments, but nothing like an acrylic splint like we learned to make. After the first 12, I’ll probably admit that as I stuck those things in there, I wasn’t sure if I did it right. Again, it was a learning curve for me. Then they’d come back and I’d have to make a couple adjustments, and then I knew I didn’t do it right. After a couple times of that, I’d really learn quick. Plus, I’d get on the phone with your technician — I believe his name is Greg, I believe he is the head of your thermoforming department. I’d get on the phone with him and I’d ask him questions: “How do I adjust this thing? It didn’t quite fit right. What do I do?” And he’d give me little tricks. In fact, I was talking to him just this week because I was having trouble getting one to fit just right, and he gave me a trick that you guys do in the lab. It was very interesting because I told him what I did, and he said, “Yeah, dentists will do that, but we don’t like it when you do that because you guys usually don’t do it right.”

MD: What trick was that?

AM: That was carefully grinding the inside of the splint, the soft material, with a little carbide bur. He said you have to grind it very, very gently. If you don’t, it will shred inside. Guess what? He was right!

MD: I think with most dentists and the splints that they have made, the impression appointment goes pretty easy. Do you use alginate or polyvinyl siloxane for your impressions that you send?

AM: I use two different materials. Mostly, I use the alginate, and I’ve been using alginate for a long, long time. How accurate that is, I don’t know because you guys recommend the polyvinyl. But I’ve just been using alginate since dental school days. Then, 3M came out with a product that seems pretty nice called Impregum™ Penta™ Soft Quick Step (3M™ ESPE™; St. Paul, Minn.). So I bought a whole bunch of that and told my staff members to start using that because I thought that would be a really nice intermediate material to use between vinyl, and at the same time, vinyl is expensive, but I told them to use that. What was very interesting is that they went back to the alginate; they like it better. They’ve just been using it so long, and they’re older, more experienced assistants. We’re set in our ways sometimes.

MD: Do you pour the models before you send them up to us?

AM: We pour them right away. In fact, I have three assistants in my office — I kind of have a busy office and I have extra assistants, and one of the things we do is, as one assistant is making the impression, the other walks down the hall and grabs it and begins pouring it right away. I don’t know if you have to pour it that quickly, but we just do because we have the team.

MD: Exactly. That’s a great point. Now, on the delivery appointment, that’s the one the dentists don’t tend to enjoy it if they’re having to make a ton of adjustments. Do you have any tips or tricks, or a standard way that you deliver these appliances? How long does it typically take you to deliver a splint?

AM: We schedule 15 minutes.

MD: Nice.

AM: Most of the time, I don’t even need the 15 minutes because it goes right in. I always have to adjust a little off the #2 area and very little off the #15, and that’s it. We’re trying to figure out a way not to have to even do that. I flame it lightly and rub it with the wet gauze, and it polishes up beautifully, which is nice. I bought the Brasseler Denture Adjustment Kit. It comes with two carbide burs and a series of three acrylic polishers. The kit is magnificent. That made my life a billion times easier, because if you adjust with it, it’s already smooth after you’ve finished your adjustment, so there’s very little polish or anything to do to it. For the most part, not to compliment you guys, but let’s face it — it comes back very good most of the time. Because of that, there is very little adjustment to be made.

MD: Do you heat up — dip — most of them in hot water before you try them in, or do you try them in first to see how the fit is?

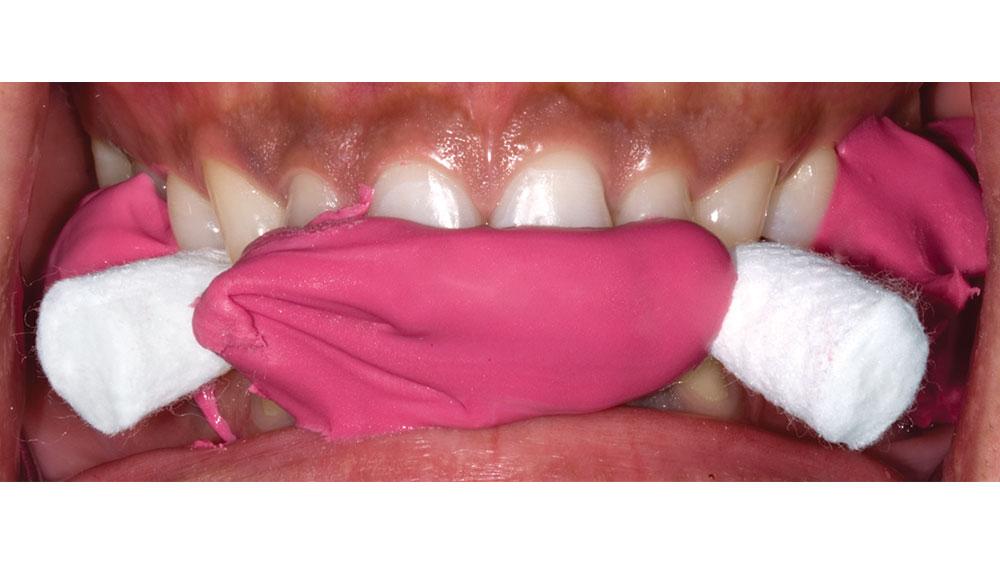

AM: I always just try it in dry first. Your tip and technique is to dip it in hot water first, but I always just try it in because I want to get the feel. If the feel is good, then I ask the patient if it feels too tight or if it feels just right because once I pop it in and pop it out myself, I know if it’s too tight or if it’s just right, especially since now I’ve done so many of them. And, again, experience is part of the game. As I got more experienced with them, they required less and less adjustment. Most of the time the fit is just a little too tight, so we just microwave some water, get it plenty good and hot (in a little cup), and then just soak it in there just for seconds. Maybe 10 seconds. Then I pop it out and put it in, and they say that feels better. So, that’s been a very, very easy thing to do. Something else that made me stop adjusting these things, and I wish you guys would’ve mailed this to me sooner, but you mailed me a card that demonstrated how to do the open bite technique. It was just a little card that showed how to squirt the material in, then have them bite on two pieces of cotton around the second bicuspids. Once we started doing that, that’s when we stopped doing any kind of real adjusting. That was probably one of the most useful things you guys have sent me.

The Open Bite Technique:A construction bite can help reduce or eliminate adjustments at the bite splint adjustment appointment. This is the only bite we can use in the lab for splint fabrication. This type of bite is taken at an open vertical dimension and is more accurate for us to construct a splint without having premature occlusal contact in the area of the second molars. Sending a fully closed bite will not help reduce the chances of having to make occlusal adjustments to the splint.

MD: We sent those postcards out to about 80,000 dentists, but you never really know the impact that it has on someone until they mention it!

AM: Not only did that help in having us stop making adjustments, but then I went to my study club and we were talking about splints, and a lot of the guys were saying it’s such a pain. I mentioned to them how, one, it’s not a pain, and two, it’s been profitable. And three, I discussed with them how to do that bite. Right before the study club, I happened to get that postcard instructing me how to do it. It was very interesting because the next day I got a call from one of my buddies, and he said, “Go over with me again how to do that bite.” I did, and then about a month later at the study club, he says: “Hey, Anton. Thanks. You made that bite real simple.” I got all the credit for it!

MD: Good for you! We’re going to run those pictures here with this article (see Figs. 1–3), since you brought it up. Tell me a little about what your front office staff has found with insurance coverage for these splints.

AM: If they have coverage, they cover it in the basic or the major category. The basic is the 80% category if you’re familiar with dental insurance billing — the major is 50% typically. Several of them don’t cover it at all. When that happens, the patient balks at the procedure. They’ll say they don’t know if they want to spend the money. I tell them either spend the money on crown and bridge procedures, or you spend the money on a little cheap splint that’s going to save you from cracking your teeth.

MD: It’s either a conservative $450 procedure now or $10,000 worth of syringes, needles, burs, handpieces and restorations 10 years from now.

AM: Yes, tens of thousands of dollars over the patient’s lifetime. It doesn’t all have to be at once: You crack a tooth, we make a crown; you crack another one, we make a crown. We’ll be doing that the rest of your life if you don’t prevent the problem now. It goes back to what we talked about earlier — recognizing it. Not just treating it, but recognizing the cause and then implementing prevention. Like, the cause of cavities is too much sugar, not flossing, all the things that we know. So we push them to brush and floss, and they have extra cleanings. Well, now the cause for what we’re talking about is traumatic occlusion. Shouldn’t we be pushing the prevention of that as well?

MD: You are absolutely right. It’s always amazing to me how many parents, when asked, will say that they hear their children grinding their teeth down the hallway at night, and yet they are still shocked to hear from their dentist that their kids might actually be grinding their teeth.

AM: Something interesting you touched on, and this is actually a double-edged sword; it’s become a problem. They all understand bruxism from their kids’ point of view, because they do hear it, they hear it every time. And it is loud! When a kid bruxes his teeth — and I have a child who does — it’s loud. This is always the response I get: “My kid does it and I can hear him down the hall. Why can’t I hear myself, or how come my husband doesn’t complain or my wife doesn’t complain?” I tell them that my theory and my reality is that adults brux differently. It’s as simple as that. You don’t hear it, your husband doesn’t hear it, nobody hears it because we don’t brux like our kids; we brux differently. How we brux differently, I don’t know, but we must.

MD: I always assumed it had to do with primary teeth versus permanent teeth. When you look at kids who brux their teeth, you notice that they are just flat. It looks like a veterinarian went in and floated the teeth like they do on a horse! When you look at adults and you see bruxism, you notice it on the cuspids, it’s on the laterals, there are a few abfraction lesions. But it’s very rare except the most extreme cases that you see all the teeth flattened off. I think the kids just have more tooth-to-tooth contact than the adults do because the primary teeth are so easy to wear through, and bruxism is louder with kids because of the increased surface area in contact. Now, I don’t know if that’s true or not, but that’s always been what I thought.

AM: That’s a good theory. That’s reasonable. At least there is an explanation or something we can look at and say that’s a reasonable explanation. Whether or not it’s true, I don’t know, but it’s certainly reasonable to look at it in that way.

The Finished Splint:

MD: I want to thank you for giving our readers a couple of great tips today. As we wrap this up, I want to congratulate you on your commitment to preventive dentistry. I think it’s admirable that you’re trying to save enamel, not destroy enamel. I don’t know if you’re a hero to your patients now, but I know you will be in 20 years when they realize that your splints have allowed them to get into their later years with, hopefully, a full and healthy dentition. Congratulations!

AM: Thank you very much.