REFERENCES

- Suchetha A. Tooth wear — a literature review. Indian Journal of Dental Sciences. 2014;5(6):116-20.

800-854-7256 USA

Explore concepts regarding multiple types and uses of nightguards for patients.

It is expected that in 2021, dentists practicing in the U.S. will make over 18 million devices that fit into the mouth and are worn during sleep. But are they all nightguards? Most patients will benefit from a custom-made appliance; however, dentists should implement simple screening techniques to determine whether that appliance should be targeted toward the treatment of bruxism, snoring and sleep apnea, or headaches. Here, we’ll explain some of the similarities and differences between these therapies, and what you can do to ensure you are providing the right treatment for your patients.

The most common reason to prescribe an occlusal splint is to defend patients’ teeth from tooth wear. The loss of some enamel due to attrition, erosion or abrasion is quite normal over a lifetime and is found in approximately 97% of the population.1 Dentists monitor this wear to determine if it is pathological or age-appropriate.

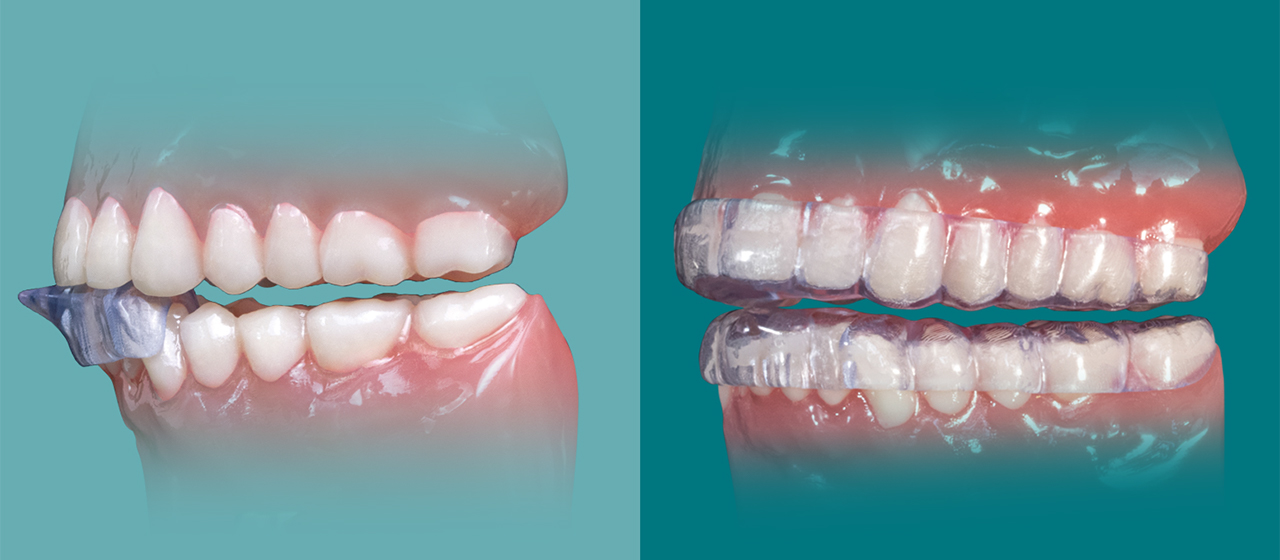

In response to obvious tooth wear that appears on the occlusal surfaces of the teeth, dentists often prescribe a hard occlusal splint like the Comfort H/S™ Bite Splint or Comfort3D™ Bite Splint. These devices are quite common and easy to deliver. As effective as these devices are in protecting dentition during sleep, they are under-prescribed in the U.S.

Prescribed due to its comfort and fit, the Comfort H/S Bite Splint is designed to alleviate the pain and damage caused by severe bruxing or clenching of the teeth.

Prescribed due to its comfort and fit, the Comfort H/S Bite Splint is designed to alleviate the pain and damage caused by severe bruxing or clenching of the teeth.

The American Dental Association estimates that over 50% of adults, or about 125 million people in the U.S., see their dentist twice a year. These visits are most often for teeth cleaning and a review of records. Since nightguards are most often associated with prevention, does this mean that American dentists have underserved their patients by some 103 million nightguards? It seems inconceivable, but the number might be even higher when adjusted for conditions that present medically — in neurology as migraines, earaches or neck pain; or in pulmonology as a symptom of untreated sleep apnea. An oral device solution may be very successful with some of these patients.

When we examine nightguards related to tooth wear alone, we find that most of the patients who receive these hard nightguards will be able to sleep very well and their teeth will be protected from wear associated with grinding, clenching, and tapping. At worst, there may be a night or two of habituation required, but after a few nights, patients respond well to long-term nightguard wear.

After being informed of the beginning signs of wear on her teeth, this patient agreed to wear the Comfort3D Bite Splint to prevent further damage caused by grinding.

– Clinical dentistry by Taylor Manalili, DDS

There is, however, a subset of patients receiving these devices who gnash their teeth during sleep so severely that they chew through the nightguard in a few weeks. Others complain that they have difficulty falling or staying asleep while wearing the appliance. This results in difficulty maintaining treatment compliance.

The inability to maintain treatment may indicate that the patient has an underlying condition that should be treated, in addition to the need of protecting dentition from wear.

Tooth wear is progressive and irreversible. The big questions for clinicians are as follows:

Providing a patient with a nightguard is only the beginning. Bruxism is a diagnosis related to the movement alone. This fuzzy etiology exists because the condition of bruxism can be associated with anxiety, TMJ and sleep apnea. In order to better understand these issues, let’s explain various concepts regarding the multiple types and uses of “nightguards” for patients.

Let’s review the nightguard for snoring and sleep apnea. Is it a nightguard, sleep device or mandibular advancement device? It can be confusing when the same terms are used for different devices used to treat a breathing-related sleep problem.

Since it is known that positioning the jaw forward opens the airway and is a recognized primary treatment path for mild to moderate sleep apnea, is it possible that delivering a hard nightguard of the wrong style could negatively affect the airway?

In 2004, Gagnon et al. from the University of Montreal published an interesting article entitled “Aggravation of respiratory disturbances by the use of an occlusal splint in apneic patients: a pilot study.” This was a very small cohort study — with only 10 patients, all with a history of snoring and a recent sleep study. The study objective was to determine the impact of occlusal splints (i.e., nightguards) on patients with preexisting sleep apnea. Although this pilot study had a small sample size, the results were remarkable, prompting the justification of sleep diagnostics for all nightguard patients. Was this caution warranted, and should the presence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) determine nightguard strategy?

Let’s take a closer look at the study: The researchers set out to examine the implications of placing a nightguard on the upper teeth of a patient who has sleep apnea. We know that placing a nightguard (occlusal splint) between the teeth changes the space between the dental arches. The lowering of the mandible affects the position of the tongue and can affect the muscles and ligaments of the oropharynx. Of course, the change is very small, but for a certain subset of patients with a narrow airway or large tongue, parafunction of the jaw, or active TMJ issues, this small change can lead to an exacerbation of their preexisting sleep apnea.

A trained dentist will screen each patient to determine risk factors and adjust therapy accordingly. It remains to be seen how over-the-counter bruxism and sleep devices will affect long-term patient care. The nightguard design used in this study was very similar to many commercially available nightguards. It was made of hard acrylic and was 1.5 mm thick in the molar region, covering all the teeth and the mid-palatal area. The lingual incisal area was 4 mm thick, tapering to 1 mm at the palate.

The study found that six out of 10 of the subjects had an increase in AHI with the splint, and the percentage of sleeping time with snoring was 40% higher during the night with the splint. This outcome demonstrates that the ADA-recommended screening for snoring and sleep apnea is certainly warranted and will improve outcomes. Given the size of the undiagnosed OSA population, this is a key public health issue.

Screening can be as simple as having the patient complete a STOP-BANG Questionnaire before prescribing a nightguard, which should help avoid some missed opportunities regarding nightguard selection. The STOP-BANG Questionnaire is sectioned into eight parts, as indicated by the survey acronym. The “STOP” portion asks four questions related to snoring, tiredness, breathing and blood pressure. The second portion, “BANG,” gathers information on body mass index (BMI), age, neck size and gender.

Click here to download Glidewell’s Sleep Solutions Kit, which includes the STOP-BANG Questionnaire for your use.

The STOP-BANG Questionnaire can be used to predict a patient’s risk for obstructive sleep apnea.

The STOP-BANG Questionnaire can be used to predict a patient’s risk for obstructive sleep apnea.

The key attribute of a nightguard for patients with preexisting snoring and sleep apnea is that it allows the dentist to position the jaw such that it will not fall back into the airway during sleep. Simply wearing the upper and lower splints, which are similar to a hard nightguard, will have an effect on airway anatomy. The ability to titrate the jaw forward in increments of 1 mm or less gives the clinician control over the jaw position to mitigate negative effects on the airway and tooth wear. As indicated above, very small changes can make a big difference.

Devices such as the Silent Nite® Sleep Appliance and the EMA® appliance will position the mandible and have full-coverage designs that will protect the teeth. For severe jaw parafunction, TAP® appliances like the dreamTAP™ are indicated to allow the mandible greater lateral excursions.

Devices like the Silent Nite Sleep Appliance, OASYS Hinge Appliance™, EMA appliance and dreamTAP appliance gently position the jaw forward during sleep.

Devices like the Silent Nite Sleep Appliance, OASYS Hinge Appliance™, EMA appliance and dreamTAP appliance gently position the jaw forward during sleep.

During his lectures, Dr. John Viviano, an Ontario, Canada-based practitioner and educator, often shares an interesting anecdote when discussing the principles of dental sleep medicine. Dr. Viviano describes a time — during the late 1990s, while working in his general dental practice before he focused his practice on sleep apnea therapy exclusively — in which he would have discussions with patients who swore they could not sleep with their nightguard. So the team would check the fit, adjust the occlusion, and then send patients away with a commitment that they work harder on compliance, only to have the patients return with the same complaints at recall.

“If I knew then what I know now, I would have asked a few simple questions, and I would have approached the case totally differently,” Dr. Viviano said. “I should have just made a sleep appliance. It would have been better for the patient and easier on me and my team.”

What about patients who present with tooth wear and suffer from headaches or migraines? It is not uncommon for these patients to grind all the way through their nightguards. Is there a way to protect their dentition while also treating the severe clenching and grinding that is destroying their teeth?

The tooth wear that initiates the conversation in the dental office should also inspire a few questions to identify migraine patients for whom a specific nightguard designed to reduce clenching force should be delivered instead of a flat-plane occlusal splint.

Migraines affect approximately 18% of women and 6% of men in the U.S. Of all migraine sufferers, 31.3% have an attack frequency of three or more per month, while 53.7% report severe impairment or the need for bed rest. Most studies of this patient population are focused on acute cases. The majority of these patients are treated with acute pharmacological interventions; however, nondrug preventive treatments for migraines tend to not be studied as thoroughly in the neurology literature.

To assess the need for therapy, migraine questions may include the following from the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Test:

Determine the total number of days from questions 1–5. A score of six or more would result in a further discussion.

Additional information doctors need to know about the patient’s headache includes the following:

A. On how many days in the last three months did you have a headache? (If a headache lasted more than one day, count each day.)

B. On a scale of 0–10, on average how painful were these headaches (where 0 equals no pain at all and 10 equals pain as bad as it can be)?

The NTI-tss Plus and the NTI OmniSplint are well-known non-pharma prophylactic treatments for clenching disorders associated with migraines. The NTI-tss Plus fits on the front teeth and has a 1 mm discluding element that holds the posterior teeth out of occlusion during sleep. This simple device reduces clenching force by some 70%.

The NTI-tss Plus and the NTI OmniSplint are effective at relieving patients’ tension headaches and migraines.

The NTI-tss Plus and the NTI OmniSplint are effective at relieving patients’ tension headaches and migraines.

The latest addition to the NTI devices, the OmniSplint, is a full-coverage device that incorporates the discluding element in the anterior to reduce tooth movement and provide support across both arches.

It is well understood that a significant number of patients in your practice require some type of nightguard to prevent tooth wear, snoring and sleep apnea, or headache- and migraine-related issues. Screening with the STOP-BANG Questionnaire or MIDAS survey will help the dental team identify those patients who require specialized nightguard treatments, including the Silent Nite or EMA appliance for airway support, or the NTI-tss Plus or OmniSplint for headaches and migraines.

The dental practice is well suited to provide this care because the tools and techniques are readily available in any office. The addition of questionnaire screening tools to new and recall appointments will open the door to higher-level discussions about nightguards, particularly regarding their clinical uses and their role in overall health and wellness.

So yes, the majority of U.S. dentists undertreat their patients who need nightguards — but starting today only requires a few questions and some more elevated discussions about nightguard function. From the practice management perspective, the delivery of occlusal guards, sleep appliances, and headache- and migraine-prevention appliances is just the kind of low-cost, high-clinical-reward therapy that the general dentist needs to increase patient retention and attract more new patients to the practice.

REFERENCES

All third-party trademarks are property of their respective owners.

Preventive Care Articles

Continuing Education

Send blog-related questions and suggestions to hello@glidewell.com.