Dental Sleep Medicine: Recognizing and Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in the Dental Practice

For patients with sleep-disordered breathing, getting a good night’s sleep can be a challenge. Sleep-disordered breathing refers to respiratory irregularities that occur when there is partial or complete cessation of breathing throughout the night, and the two most common conditions are snoring and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which can be treated by a dentist, after physician diagnosis.

Unfortunately, because snoring and apnea occur when the patient is sleeping, he or she may be the last to know about the problem. In addition to being unaware of their condition, many patients do not realize the true necessity of adequate sleep in order for the body to function properly. Sleep plays an important role in good health and mental, physical and emotional well-being. Loss of sleep can contribute to several health problems, with short-term effects including increased stress, mood disruption and impaired concentration.1 Long-term effects include an increased risk for diabetes, breast cancer, high blood pressure, depression, stroke and obesity.1

Adults should aim for seven to eight hours of quality sleep each night to function optimally. Sleep provides the body and mind with a chance to rest and shut off for the night, and gives the body the opportunity to repair and restore itself. Sufficient sleep allows the body to process information and improves a person’s memory and ability to learn. Because sleep also plays a major role in appetite and metabolism, it is involved in weight control.2

Dental sleep medicine has been identified as one of the fastest-growing areas of dental practice. Because patients tend to see their dentist more frequently than they see their physician,3 dentists are in a unique position to screen for and treat snoring and OSA. Fortunately, dental sleep medicine is a straightforward practice area, affording significant opportunities to help improve a patient’s overall health.

Because patients tend to see their dentist more frequently than they see their physician, dentists are in a unique position to screen for and treat snoring and OSA.

A good night’s sleep helps to optimize health.

THE RELATIONSHIP: SNORING, OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA AND BRUXISM

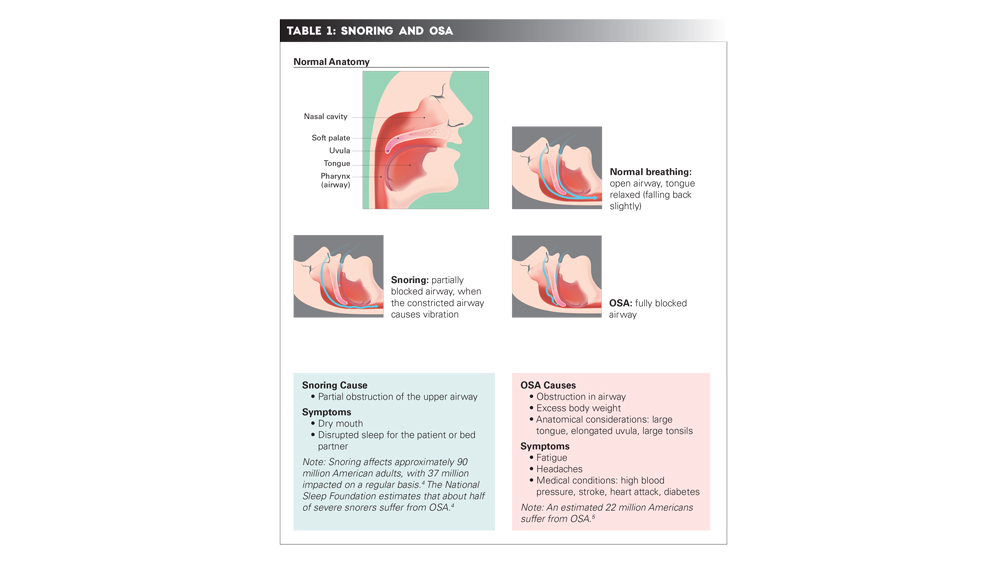

In order to help patients achieve a restful sleep and mitigate nighttime clenching and grinding, it’s important to understand the relationship between snoring, obstructive sleep apnea and bruxism. Snoring is caused by partial obstruction of the upper airway. During the sleep cycle, the muscles of the throat soften and the tongue relaxes, narrowing the airway. When a breath is taken in, the walls of the throat begin to vibrate, leading to the sound recognized as snoring. The narrower this passageway becomes, the greater the vibration and the louder the snore. Loud snoring not only interrupts the bed partner’s sleep cycle, but may also be a sign of a medical condition. Snoring, especially loud snoring, is associated with obstructive sleep apnea (Table 1).

OSA occurs when the walls of the throat collapse, completely blocking the airway and creating a cessation of breathing. OSA can cause breathing to repeatedly stop and start during sleep as the airway intermittently becomes blocked, limiting the amount of air that reaches the lungs. This can result in loud snoring, gasping or choking as the body tries to breathe. The brain and body become oxygen-deprived, and the person may wake up a few times or, in severe cases, hundreds of times per night. This leads to a person feeling tired the next day, despite what may seem like a full night’s sleep.

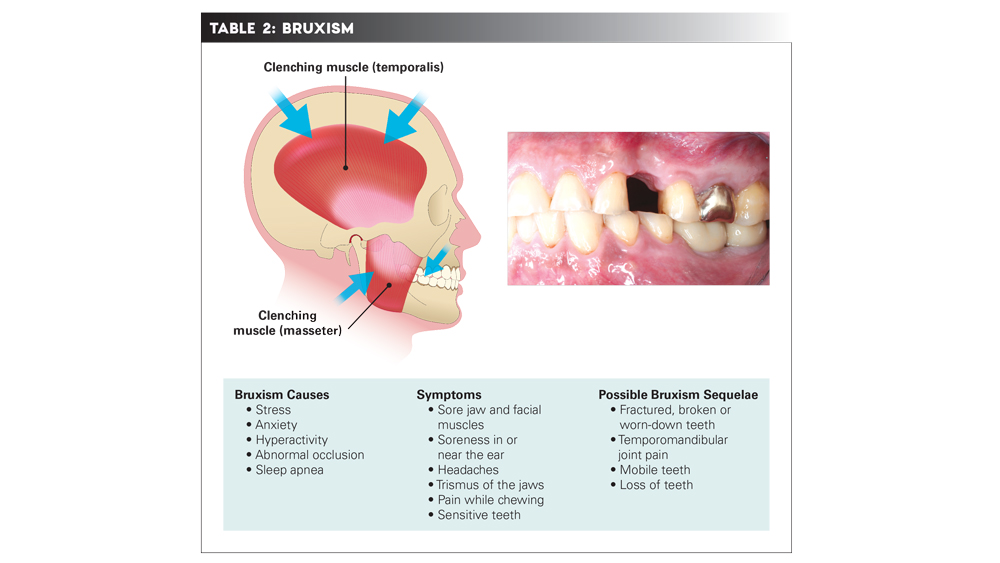

Sleep bruxism, characterized by grinding or clenching of the teeth, is considered a sleep-related movement disorder, and not a breathing disorder (Table 2). Patients with bruxism may unconsciously clench or grind their teeth while awake or asleep. In OSA sufferers, bruxism may be an unconscious response to the collapsed airway, as jaw muscles are tightened in an effort to prevent the restriction of airflow.5 Chronic grinding and clenching of the jaw during sleep can create serious oral health problems, including misalignment of the dental bite, temporomandibular joint disorder, and chipped, cracked or abfracted teeth. Signs of grinding the teeth while asleep include headaches upon waking, shoulder and neck pain, and trismus of the jaws.

IMPORTANCE OF SCREENING

An estimated 22 million people suffer from OSA, with 80 percent of moderate to severe cases going undiagnosed.4 Thus, identifying OSA in patients can help eliminate conditions that, if left untreated, could lead to serious consequences. Screening for OSA offers a holistic approach to patient care, and fortunately, dentists are in a unique position as health care providers who not only see patients several times annually, but also have access to the oral cavity.

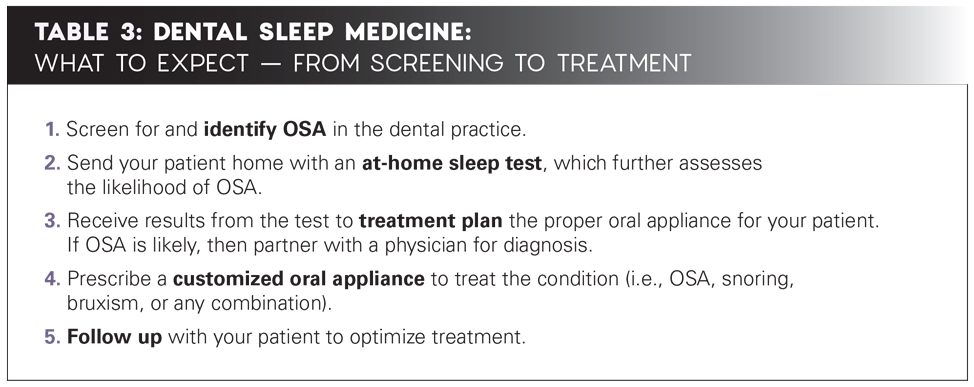

When a dentist screens the patient in the office and identifies possible OSA, further evaluation with an at-home sleep test can be initiated on the same day. The results of this test can determine the next steps in treatment planning. While many options are available to treat OSA, including oral appliance therapy, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, and surgical measures, many patients either cannot tolerate or are unwilling to use the CPAP device, or are not recommended for surgical measures. Ultimately, upon proper diagnosis, a customized oral appliance can lead to a successful, minimally invasive treatment outcome.

Because patients tend to see their dentist more frequently than they see their physician, dentists are in a unique position to screen for and treat snoring and OSA.

The OSA screening exam includes a thorough discussion of the patient's health history.

PATIENT EVALUATION

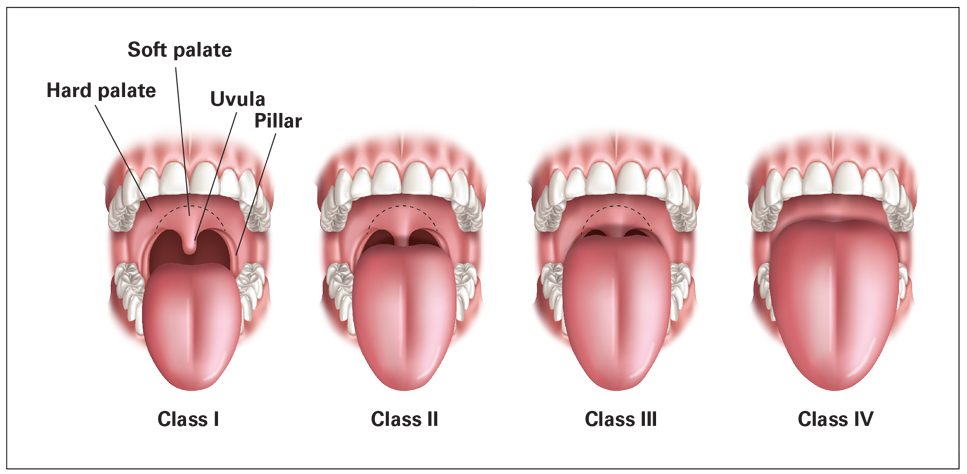

Consider that examining the oral cavity for cancer goes hand in hand with an OSA screening exam. The first step in this straightforward process includes listening to the patient and conducting a thorough health history to identify any factors connected with OSA, such as loud snoring, bruxism, high blood pressure, smoking, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity and sleep apnea in the family.6 Population-based studies have shown that OSA is more common in men than in women,7 and older age as well as alcohol ingestion are also factors.8 Next, conduct a physical evaluation of anatomical characteristics of the tongue, tonsils, uvula, airway and neck, with attention to enlarged or elongated proportions (Figs. 1a, 1b). Observe the palate, and assign a Mallampati grade to the patient’s airway (Fig. 2). Additionally, encourage the patient to fill out the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, which is a questionnaire designed to measure a person’s general level of daytime sleepiness or average sleep propensity during daily activities.

Figure 1a

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

Figure 1b

Figures 1a, 1b: An oral airway evaluation can help dentists identify patients likely to have OSA. Figure 1a shows a patient with a normal airway. Figure 1b shows a patient with an elongated uvula, scalloped tongue and elevated palate; this patient is a heavy snorer and was diagnosed as having mild sleep apnea.

An oral airway evaluation can help dentists identify patients likely to have OSA.

Figure 2: The Mallampati classification can be predictive of apnea, with scores that include complete visualization of the soft palate, uvula and pillars (Class I), visualization of the soft palate and uvula (Class II), visualization of only the base of the uvula (Class III), and a soft palate that is not visible (Class IV).

After the completion of the in-office screening, a recommendation can be made for an at-home sleep test, and a GEMPro Wellness Monitor (Glidewell Direct; Irvine, Calif.) may be sent home with the patient. The GEMPro is a sleep test device that provides critical information about the intensity of bruxism, snoring and apnea events that occur during sleep. While it does not diagnose OSA, it’s an important tool for dentists to have, as it provides objective data on the cause of parafunctional activity and can assess the likelihood of OSA.

If the patient requires treatment for bruxing, snoring or OSA, the correct appliance is treatment planned by the dentist (Table 3). Note that placing an inappropriate oral appliance on a patient who has OSA, but has not yet been identified, could possibly block the airway even more, potentially causing OSA or creating severe OSA in a mild or moderate case. This is just one more important reason why screening is critical.

CONCLUSION

Patients want to feel more energized and enjoy better health, but many undiagnosed OSA sufferers believe that feeling tired is normal. They are accustomed to waking up several times during the night, so they do not consider this to be a problem. Through screening for OSA in the practice, dentists can educate patients about the importance of getting a good night’s sleep. This goes along with a discussion of the health concerns associated with OSA, as well as the positive results that can be gained through oral appliance therapy.

Patients fill out an Epworth Sleepiness Scale questionnaire to measure their general level of daytime sleepiness.

With a small investment of time to learn the intricacies of dental sleep medicine, just about any dentist can implement this service into the practice. Once incorporated, sleep medicine can benefit the patient’s health and the dentist’s practice and productivity.

A UNIQUE START: ONE DENTIST'S QUEST TO HELP PATIENTS WITH OSA

Dentists have the opportunity to help patients in so many different ways, from preventive care to full-mouth reconstructions. For Dr. Suzanne Haley, a general dentist practicing in St. Simons Island, Georgia, dental sleep medicine has become a passion. “I became interested in dental sleep medicine when my husband, who is a pilot and shares a ‘crash pad’ apartment with six other pilots, was asked to leave due to his very loud snoring,” she explained. “I had learned about at-home sleep testing, and I became intrigued by the information it provided regarding treating snoring and sleep apnea in the dental office. I also had read many articles about dentists treating snoring and sleep apnea with dental appliances.”

Dr. Haley encouraged her husband to use the GEMPro Wellness Monitor, a home sleep test device that provides information on the amount of bruxism, intensity of snoring, and desaturations and apnea events that occur during sleep. “A certified sleep physician evaluated his data, and his diagnosis was mild sleep apnea with bruxing and snoring,” she said. “An oral appliance was custom-fabricated for him, and the treatment was successful. I decided then to implement dental sleep medicine into my dental practice and have successfully treated patients with OSA ever since.”

References

- ^Lavigne GJ, Cistulli PA, Smith MT. Sleep medicine for dentists: a practical overview. Hanover Park: Quintessence; 2009. 179 p.

- ^Attanasio R, Bailey DR. Dental management of sleep disorders. Ames: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. 91-2 p.

- ^Strauss SM, Alfano MC, Shelley D, Fulmer T. Identifying unaddressed systemic health conditions at dental visits: patients who visited dental practices but not general health care providers in 2008. Am J Public Health. 2012 Feb;102(2):253-5.

- ^Sleep apnea information for clinicians [internet]. Washington, D.C.: American Sleep Apnea Association; c2017 [cited 2017 June 21]. Available from: https://www.sleepapnea.org/learn/sleep-apnea-information-clinicians.

- ^Lee-Chiong Jr TL, Sateia MJ, Carskadon MA. Sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2002. 237-8 p.

- ^Who is at risk for sleep apnea? [internet]. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [updated 2012 July 10; cited 2017 June 21]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sleepapnea/atrisk.

- ^Lin CM, Davidson TM, Ancoli-Israel S. Gender differences in obstructive sleep apnea and treatment implications. Sleep Med Rev. 2008 Dec;12(6):481-96.

- ^Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008 Feb 15;5(2):136-43.