One-on-One with Dr. Michael DiTolla: 20 Questions with Dr. Paul Homoly

One of the interesting things that happens when dentists come and take a tour of our lab, is how surprised they are at all the full arch and full mouth cases being fabricated. The solo practitioner who does a lot of single tooth dentistry never realized how many dentists were doing these big cases. A lot of times it seems as if a light bulb pops up over their head as they realize, “Gosh, I don’t have to be Paul Homoly or Bill Strupp or David Hornbrook to do this type of dentistry.” Especially when the case they are looking at is from a dentist in some tiny town in Kansas who’s doing this full arch case and he sends in one or two a month to the lab. In this article I speak with Dr. Paul Homoly about how doctors can get comfortable with presenting larger cases. If there is a better system to mastering patient communication than Paul’s, I haven’t seen it.

Question 1: To get this started, for our readers who are unfamiliar with your career progression: Take me through your career from dental school graduation through dental practice to what you’re doing today.

Dr. Paul Homoly: I graduated in 1975 from the University of Illinois and went directly to the United States Navy. From 1975 to 1977 I had a great experience in the Navy, where I practiced largely in the Oral Surgery department. Although I’m a general dentist, I was lucky enough to perform oral surgery for two years, doing dentoalveolar surgery, impactions and a lot of trauma. So when I got out, I was really up to speed as far as my confidence with dentoalveolar surgery.

From the Navy, I went right into private practice, immediately enrolled at The Pankey Institute and the Dawson Center, and started studying dental implants. I placed my first dental implant in 1978. In 1979 it became legal and ethical for professionals to market. I hired a PR ad agency and made a decision back then that I wanted to exclusively practice implant and restorative dentistry. And low and behold, by 1983 that’s exactly what I was doing.

I moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, and that’s when I got involved with the American Academy of Implant Dentistry, The Pankey Institute and the Dawson Center. Dr. Carl Misch and I became close personal friends back in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Carl and I, his brother and a few other faculty members started the Misch International Implant Institute — I think I’m Carl’s second faculty member there. I taught with Carl for more than 20 years at the Misch Institute, and I still teach for him.

From 1983 to 1995, my practice just grew and grew. I had a small, commercial dental laboratory inside my office. About one-third of my patients were referred from other dentists and I enjoyed a very wide regional reputation in implant dentistry. I served at all levels of office of the Southern District of the American Academy of Implant Dentistry, and I was visiting faculty of about seven different dental schools nationwide. Back then, when implants were new, there was a tremendous demand for clinical lecturing, so I began clinical lecturing in 1981.

In 1993, I suffered an eye disability. I was born with cross-eyes, which is a congenital issue. Consequently, disability insurance didn’t help me much. My surgeon repaired the eye, but he said due to my working in a surgical environment, it would probably cross again. He fixed it a second time, but could not fix it a third. The eye crossed again in 1995 and that’s when I was forced to retire from the clinical aspect of dentistry. It was 20 years to the date. I had a great 20 years.

In those 20 years, I restored around 4,500 patients with partial or full mouth reconstruction and dental implants, and I really pioneered some early surgical procedures. I got involved in the pioneering networks of developing marketing and business plans for high-end restorative practices. I actually started my consulting business about 10 years before I left the practice of dentistry; I founded my consulting and speaking company in 1986. This is about 10 years prior to my retirement in dentistry, so I had a solid Plan B in place. And I did not retire in the economic sense, I retired in the clinical sense; I still needed to eat, you know how that goes.

In 1995, I went into full time practice consulting. Basically, I went into dental offices and helped them create a business plan and communication plan to develop a high-end restorative practice. I’ve been out of clinical dentistry for the last 15 years, after practicing for 20 years, and there is no question that I understand more about the business aspect of dentistry now than I ever did.

As we talked about earlier, Mike, when you’re in private practice, you typically just see your own stuff. But in the last 15 years I’ve seen everybody’s stuff. That’s the way I get a much grander view, an overview, of what the truth is relative to full mouth dentistry in the United States. How many dentists are really doing it? And how easy is it to implement? All the gurus standing at the front of the room preaching about: “You should do it like this. You should do it like that.” Is that really the case? And you’re in a great position, too; if there’s ever a teller of the truth, it’s the dental laboratory industry because you see all the good, the bad and the ugly coming through there.

Q2: You’re absolutely right. We see how many units are single unit dentistry, and you can look around at a model and see a tooth behind the one that’s been prepped that appears to be in the same broken down shape. And you wonder why the dentist is not just doing both of those preps at the same time. Of course the patient has to say yes. I think you’ve got a fantastic name for the program you’re teaching now: “Making it Easy for Patients to Say ‘Yes.’” Because most dentists who’ve been in practice for more than 10 years say they’ve got their clinical skills dialed in. The thing that really holds them back is their patients’ not saying yes. To start this off, let’s talk a little about your concept of right side patients versus left side patients.

PH: The distinction between left side and right side patients is absolutely mandatory for a dentist to get. If they want to reduce the complexity of full mouth dentistry or complete care dentistry or even cosmetic dentistry, there needs to be an understanding.

Let me back up a little bit from that question — for me to dial into that left side/right side thing, you’ve got to get this aspect of it first. Let’s say in the first 10 years of a dentists’ practice, the growth is really driven by the clinical skills: Greater knowledge of occlusion, greater hand speed, greater confidence around the mouth. The first 10 years, typically, are all about acquisition of clinical skills. But after that first eight to 10 years, what happens is that a lot of practices will flatten out. They’ll plateau as far as their growth is concerned; it’s kind of like they hit a ceiling, they reach capacity. That’s the point where fixing more teeth won’t fix the practice anymore. They’ve learned as much as they can, or as much as they think they can. What happens is the early growth brought on by acquisition of clinical skills has a silent antagonist accompanying it. And that silent antagonist is complexity. Complexity accompanying the early growth of the practice compounds over time. What happens is, as the practices grow, as we go from three assistants to five to seven, as we go from 1,000 square feet to 1,500 to 2,000, when we move from simple dentistry to cosmetic dentistry to rehabilitative dentistry to implant dentistry — what happens is this complexity increases. The complexity is greater than their ability to manage it and that’s when practices flatten out. That’s when they hit their plateau.

To get off the plateau, to get to another level, many dentists resort to what’s worked for them in the past. And that is, when they are on the plateau, they go back into clinical education. They take another course on occlusion, another course on implants, another course on bonding. After you’ve had four or five courses, taking five or six more isn’t going to create much more leverage in your practice. The original clinical skills that got you on the plateau are not the same skills to get you off it. To get where you’re going you need to look at what issues are holding you back.

Typically, it isn’t the acquisition of clinical skills holding dentists back. What holds dentists back is their inability to deal with the complexity brought on by success. Nobody talks about that. It’s like everybody talks about: Let’s be more successful. Let’s pursue excellence. Let’s get to the next level. But nobody talks about the price you have to pay to get to the next level. Everybody wants to go to heaven but nobody wants to talk about dying.

Recently, I spoke with a dentist who’s been in practice eight to 10 years. He’s taken a bunch of courses, and is using a good lab. He’s doing things right, but he’s just stuck. You know what I’m saying? For that dentist to really get where he wants to go, he needs to bring in a new set of skills and those skills aren’t related to anything clinical. These skills are related to his ability to lead. They are leadership competencies, which include communication, listening, bringing out the best in people, managing conflict, delegation and time management. All things most dentists simply don’t want to think about. They want to be able to hire somebody to do all that stuff. But you know what? You can’t hire success. You have to grow into it.

But after that first eight to 10 years, what happens is that a lot of practices will flatten out. They’ll plateau as far as their growth is concerned; it’s kind of like they hit a ceiling, they reach capacity. That’s the point where fixing more teeth won’t fix the practice anymore.

The case acceptance process is about where he wants to go and reducing the complexity and anxiety of the acceptance process. The case acceptance process is the single most complex process we have in the sophisticated dental practice. Look at what goes into it. First, you have all the marketing and you must get the people in. Second, you have all the issues related to the new patient examination. You’ve got the examination, the diagnosis, the treatment planning, the case presentation, the photography, the radiology, the referral relationships, the talking to physicians, talking to the lab, talking to the specialists, dealing with the medical history, dealing with the patient, dealing with the management of complications and failures — it’s a hugely complex topic. Now, the “Making It Easy” process is designed to reduce this complexity. It starts out with making some simple distinctions among patients. That is where this left side/right side distinction comes in.

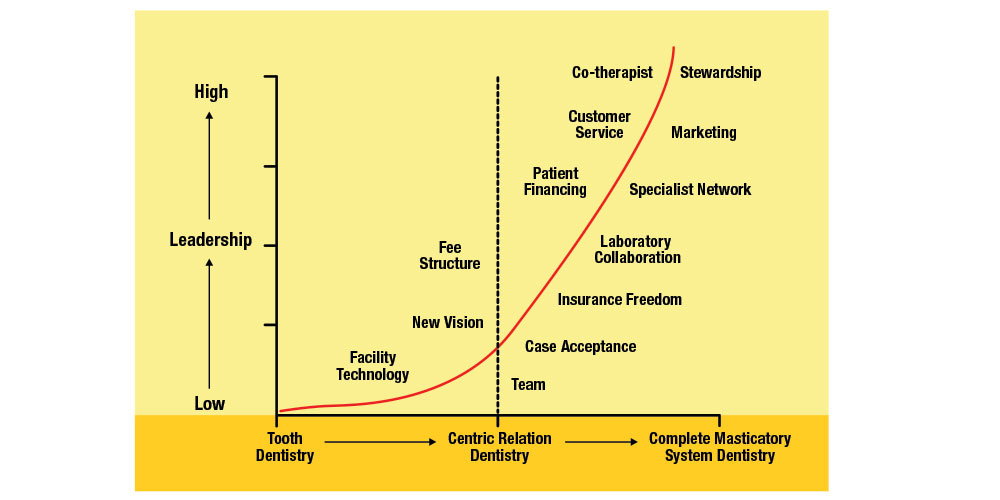

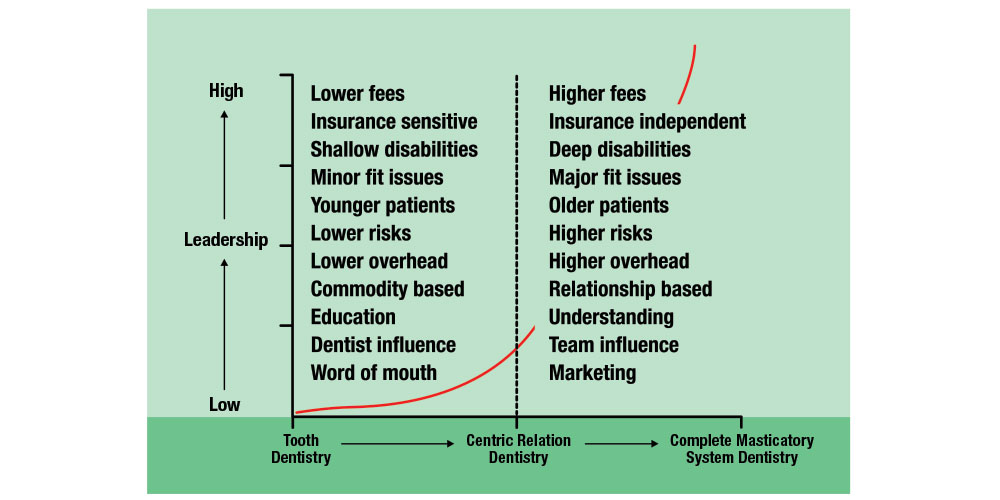

The above graph shows the continuum of care. All the way to the left on the horizontal axis is simple tooth dentistry. All the way to the right on the horizontal axis is complete full mouth reconstruction. Above halfway in the middle is the dotted line going up the chart labeled “Centric Relation Dentistry.” That’s where the complexity reaches the point when the operator would need to change the vertical dimension, the plane of occlusion, the condylar position or the anterior guidance. This is where the case would need to go on an articulator. Typically, this is about four units of crown and bridge. To the left of that line is three units or less. Everything to the right of that dotted line is four units or more. I’m making a distinction between simple care dentistry, patients who require three or less units and patients who require four or more units.

On page 10 of my book, there’s a pretty complete description of the distinctions between these patients. Typically, right side patients are those whose clinical care requires four or more units, or typically greater than $3,500. Left side patients are those requiring three or fewer units, or typically less than $3,500.

These positions are important to note because these two groups of patients behave very differently. One of the most significant differences between the two groups of patients is found on the chart on page 10 (see below). The right side patient has a deep disability. They have something that is not right in their life because of their teeth. Something about their teeth is interfering with their life — their ability to enjoy themselves, their confidence, their appearance and their ability to speak. Left side patients frequently have no disability or very shallow disability. This disability relates to how does the intraoral condition negatively affect the patient’s life. Typically, left side patients have no disability at all. Right side patients have a major fit issue. A fit issue is how does dentistry fits into a patient’s life. And by fit, I mean the budget, the time and the hassle factors. Right side patients have significant fit issues because of the cost, because of the time involved. Left side patients, it’s a $1,200 fee. Most patients are going to have dental insurance — they’re going to pick up half of that — and they can put the other half on a credit card. So there are not significant fit issues on the left side.

The third and more important distinctions between left and right side patients is that left side patients — this is really key to this whole discussion — left side patients are those who have minimal conditions in their mouth and require patient education for them to accept care. In other words, most of them don’t even know they’ve got the conditions in their mouth. There’s incipient Class II decay, or an asymptomatic periapical abscess, or an asymptomatic unerupted third molar. They don’t even know they have it. So we have to go through an education process, a show-and-tell to demonstrate the problem. We educate them into readiness.

On the right side, it’s a completely different conversation. Right side patients have a significant dental disease impacting their life. You don’t have to educate the guy with a partial denture that’s eating a hole in his cheek. You don’t have to educate the woman who has dark brown composite fillings across the front of her teeth and she’s horribly embarrassed. People on the right side are watching it and they know what the problem is. They don’t know all the problems, but they know their main problem.

Dr. Michael DiTolla: She knows that she has to put her hand in front of her teeth when she smiles, right?

PH: Right. That’s the disability, Mike, right there. We need to spend far less time educating these people and far more time understanding them. Instead of preaching to them about plaque and parafunction like we do on the left side, we need to understand these people and how this dentistry will fit into their life. It’s a different conversation.

Q3: It’s funny because, as you’re telling me this, I remember a couple of dentists who’ve come up to me, complaining that they wish dentistry were more like cardiology. And they seem almost jealous of being able to tell a patient: “You need this, this and this. You need your whole upper arch redone.” And in cardiology the implication is, “You need to have this done or you’ll die.” So people find a way to have it done. And I talk to dentists who wish dentistry wasn’t optional. But the reality is, it is. You can’t take a larger case, a right side case, and treat it like you would a smaller one and expect the patients to say yes.

PH: Exactly right, Mike. You hit it right on the head. You know, it’s funny you should say that some dentists wish it was like cardiology. They’re stuck on the plateau. They want to educate the patient to the point where the patient will be educated into readiness. That’s why I said the acquisition of greater clinical skill won’t get these dentists off the plateau. What the dentist needs to do is communicate with the patient in a different way, a nonclinical way. So the distinction between left and right side is absolutely fundamental to reducing complexity relative to the case acceptance process. What I recommend is that the new patient experience is bifurcated. In other words, I don’t advocate a single new patient experience for all patients. Rather, there are two distinct, new patient experiences: One that’s suitable for a left side patient, one that’s suitable for a right side patient.

Q4: I think that’s brilliant because as you go out to some of these clinical education institutes that are out there, it seems like the message is to treat everybody like a right side patient. They’re not saying create right side patients, but to treat everybody that way and approach everybody the same way. And I’ve always felt that it’s not the correct way to do it, and that seems to be what you’re pointing out. So if we have right side patients — where the treatment fee for the case may be, say, over $3,500 — and then a left side patient, which are patients under $3,500, what’s a good mix of right side patients versus left side patients for an average dental practice?

PH: I think most general dentists would be extremely wise to look at a practice that’s 20% to 30% on the right side and 70% to 80% on the left side. Here’s why: There’s a lot of wisdom in having a very strong left side practice. Number one: Left side patients are easier to recruit or market. Two, the sales cycle is shorter. Three, there’s less stress related to the left side. Four, the left side stays more intact in downturns of the economy. Finally, left side practices are easier to sell and to transition. The left side sustains the cash flow. In other words, there’s a lot of safety in the business model of a left side practice.

Now, the problem with left side practices is that, for some of us, it can get boring and routine. People who are going to read this article want to be able to grow intellectually and they want to be able to self-actualize. They want to perform the dentistry they love to do, and that’s really the right side stuff.

Right side dentistry to the inexperienced dentist is frightening. But for dentists equipped to do it, who are knowledgeable and who have the experience and confidence, it becomes a joy. The problem with the right side is that it’s very fickle in terms of economic downturns. When the economy sours, the right side is one of the first things to dry up. Next, the sales cycle is much longer. A right side patient may take two or three years to get ready to rehabilitate their mouth. And right side practices are very difficult to transition; it’s very difficult to sell a right side practice. Ask me how I know (laughs). So, what the smart GP will do is have a small right side practice as part of a very large left side practice. It will be the left side practice providing the safety and the cash flow, and the right side practice creates the self-actualization and the buzz.

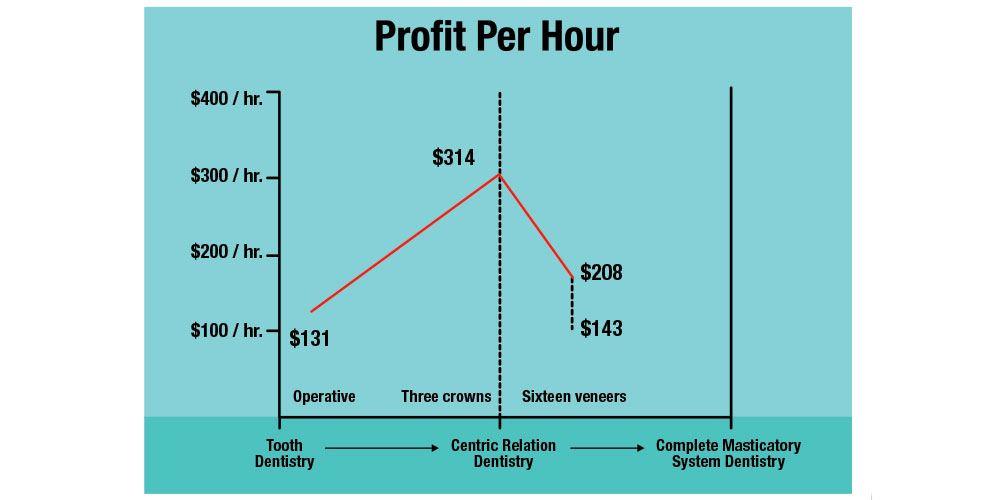

Q5: One of the things I find interesting in your book is that you mention, regarding the bigger right side cases versus the left side, everybody tends to think that the right side is where all the money is. But you specifically talk about the profitability of left side procedures versus right side procedures.

PH: To prove this, simply line up 100 dentists who’ve done their first 20 right side cases. And out of 100 dentists, you’d probably find two that were telling you the truth who would say they were profitable at it. Right side dentistry has huge inherent risk. The biggest risk in right side dentistry is the amount of time we put in the case. We always underestimate the amount of time in the diagnosis and treatment plan, the amount of time in the intraoperative remakes (redoing units), the amount of time in postoperative adjustment, the amount of time you spend with the lab and the specialist. Typically, we underestimate our time by about 50%.

When I perform fee analysis for rookie doctors in the right side world, I discover their net fee per hour when they’re doing one and two units of crown and bridge is typically greater than their net fee per hour doing 20 veneers. So the patient fee is much higher, but the net fee per hour can be much lower if the dentist doesn’t realize the additional risk in time, in intraoperative remake and in variability of the treatment plan.

Mike, you know darn well that if you sit down and let’s say you treatment plan a $25,000 crown and bridge case, that treatment plan as you present it is rarely the one you actually perform. There are always changes, and those changes add up over time. And the big killer with right side cases is the additional time practitioners need to put into these cases.

Q6: It’s pretty rare that a doctor probably underestimates the time it’s going to take him to do two crowns by 50% because it’s such a routine procedure to do a crown on #18 and #19. There just aren’t that many variables. I remember when veneers first became really popular back in 1995, and dentists were charging the same — or maybe even a little less — for veneers than for a crown. And by the time they got through all the steps of prepping and temporizing, and bonding them on, and sawing through the contacts, and finishing the margins, there were a lot of dentists that were unsatisfied with these cosmetic cases but they couldn’t quite put their finger on why. But I think they knew they really weren’t making any money on this. And had it been 8 or 10 crowns, they would have done better in terms of profit.

PH: Absolutely. The same thing happened in implant dentistry. I remember my first 10 years of practice were completely different than my last 10 years. I guarantee you. And you know what, it got to the point with these complex, implant cases that I was hoping for a simple case to walk in. Just give me a 3-unit bridge — something that I can do profitably. I don’t want to start harvesting bone and moving sinuses and all this heroic stuff. I mean, gosh, it looked great in front of a lecture hall; but in terms of profitability and post-op…the truth of right side dentistry is that it takes a village to do it well. It really does. One of the big motivators of me writing this book is to reduce the complexity around the dentists who do this dentistry. It takes such a heroic attitude on the part of the dentist to really to embrace it at the level and do it well. You have to put your heart and soul into this stuff, and if you don’t put your heart and soul into it, stay on the left side.

Q7: You‘re talking about hoping something easy would walk in the door. Dr. Gordon Christensen has been saying for the last 10 years that GPs should be placing implants. And Nobel Biocare has spent an awful lot of money trying to get GPs to start placing implants. And a lot of the GPs that I talk to about placing implants say: “I’ve got enough crown and bridge to keep me happy. Why would I want to do that?” They seem to be rejecting the right side part of the graph.

PH: I don’t blame them, to tell you the truth. I think 20 years ago it would’ve made sense for a GP to do dental implants, Mike, because the specialists really hadn’t embraced it. But if I was a GP right now, I would look really carefully at my own skill set and ask myself: “What is my unique ability here? What do I do really well and really profitably?” For most GPs, that’s going to be operative, crown and bridge, and removable. Then I would build an alliance relationship with a smart specialist whose unique ability was surgical placement of dental implants. If you can look at it from the standpoint of a division of labor, the specialist can place the implant faster and more profitably and safer than most GPs can. Understand, I was a GP who made my living in dental implants; I’m not speaking hearsay. I’m talking about how to reduce the complexity in your dental life. If I can share the risk — and when I say risk, I’m not only talking about medicolegal risk, I’m mostly talking about the business risk — if I can share the business risk with the practitioner who has this unique ability, then it makes the most sense for me to delegate that aspect of care I’m not 100% on.

Now, if the general dentist wants to do implant dentistry as a hobby, that’s a different conversation. There are a lot of dentists who would just like to be able to put in a couple of implants a year and restore them and feel good about it, and I’m all for that. But don’t try to make a living at it, unless you’re going to be doing $300,000 to $400,000 a year in surgery. That way, you’re doing enough surgery so you can be competent and fast and minimize your postoperative complications on a lot of this stuff. I am not one of these guys running around encouraging GPs to start placing dental implants. If I’ve got a good surgical specialist in my region that can place them before me and I can build an alliance relationship, why not offer the patient the best in terms of standard of care? Everybody, do what you’re best at and don’t try to be the hero.

Q8: Let’s talk about something that you’ve probably seen in a lot of practices before. Let’s say a right side patient has broken the buccal cusp off tooth #30 and it’s cutting their cheek, so they head into their dentist’s office. Talk about what you think is the best way to treatment plan for the patient with a broken tooth who happens to be a right side patient.

PH: The heart of it is understanding the distinction between a condition and a disability. The first distinction we talked about was left side verses right side. And remember, Mike, the reason for the distinction is to change our behavior, not the patient’s behavior. So the left side/right side distinction will basically alter the way we perform the new patient process. Left side patients get a particular process, right side patients get a different process.

So the distinction we’re talking about is between the condition and the disability. The condition is the intraoral finding that’s outside of normal limits — the broken cusp you just mentioned. Now the disability is: How does that broken cusp get in the way of the patient’s life? In other words, what’s the emotional component of that? Disabilities are typically emotional in nature. For example: a patient with discolored front fillings. The condition is the front fillings; the disability would be the emotional component. And maybe that’s something like the patient being embarrassed at work. The condition might be a lower denture. The condition is being edentulous and the patient wears the lower denture. The disability might be that it interferes with this person’s ability to play tennis or to exercise.

So now to answer your question: The patient who comes in with a broken cusp, the first question I ask is: “Are you aware you have a broken cusp on this tooth? Are you aware of that?” Then, I’m going to gauge the patient’s level of awareness. See if they acknowledge and say, “Yes, I’m aware of it.” The second thing I’m going to do here is to illustrate the condition to the patient in a way they’ll get it. An illustration is different than education. Education is you telling the patient what the condition is by using words they don’t understand. An illustration is a comparison to something the patient already understands.

For years, it was beat into my brain that the way to build good relationships in the dental practice is a thorough examination. And that’s true, Mike — if the patient wants an examination. But how do you build a relationship with a patient with a procedure that the patient doesn’t want or isn’t ready for?

For example, Mike, you come in, I look in your mouth, and you’ve got a broken cusp. I’ll say, “Mike, did you know that you had a broken filling, a broken cusp?” You’ll say yes, no or maybe, and I’ll say: “A broken filling can be like a crack in the windshield. It starts small and it can get big.” And at this point, I would show you an intraoral photograph of that condition. I’ll say: “Mike, here is the crack in your windshield, right here. Here’s the break.”

Then I would typically offer you the consequence of that condition if left untreated — but not in you, Mike, but a patient similar to you. I would say: “Mike, conditions like this can lead to the tooth breaking. It could cause the tooth to be lost, and some patients experience significant toothaches relative to cracks just like this.” See, I’m not threatening you, Mike, I’m not telling you this is going to happen to you. Because the fact is, I don’t know whether that’s going to happen to you.

Q9: That is a great point. Because I always thought that it was disingenuous to try and be a fortune teller and predict what’s going to happen in somebody’s mouth.

PH: Exactly, because we don’t know. And hygienists do it all the time and dentists do it all the time with periodontal disease: “Well, if you don’t get root planing, you’re going to lose your teeth.” We don’t know that. We don’t know that to be the case. But what we do know is that patients with cracks in their fillings similar to what you have can lead to the tooth cracking and breaking off.

Next, I would determine your level of concern relative to that consequence. And I would say, “Mike, does something like that concern you?” The four parts — and this is in the Discovery Guide Dialogues — are: one, curiosity — “are you aware that you have it”; two, illustration — “this condition is like…,” then I would compare it to something; three, consequences — “patients like you who have similar conditions, if is left untreated. can lead to…”; and four, concern — does something like this concern you?

So it would sound like: “Mike, did you know that you have a broken filling back here? Well, fillings can break sometimes. It’s kind of like the bottom plate in a stack of china dishes; the pressure from the top plates can crack it. Here’s a photograph I took of your mouth showing this broken plate. Now, many patients of mine who’ve had similar cracked fillings find that food can pack in there or they can get an on and off toothache. In more severe conditions, the tooth can crack and, in some cases, the tooth can be lost. Is this something that you’d want to avoid?” See what I’m doing? I’m making you aware of the condition and I’m making you aware of the consequences. Most dentists don’t evaluate the concern relative to the condition. Because many conditions out there have no disability at all attached to them. And for the dentist to simply look at the patient and say, “You have a broken tooth, you need a crown,” is probably the most common mortal sin that most dentists make, right there.

MD: I can guarantee you that is occurring in probably at least 1,000 dental offices as we speak!

PH: It’s like the old movie “Young Frankenstein.” Remember that? Dr. Victor von Frankenstein goes to Transylvania, he gets off the train, he meets Igor for the first time. He looks at Igor, looks at Igor’s hump, and he says, “I don’t mean to embarrass you, but I’m a prominent surgeon and I can help you with that hump.” And do you remember what Igor says? “What hump?”

See, we look at a patient smile, we see a buccal cusp broken off tooth #30. You say, “Hey, you’ve got a broken filling, you need a crown.” The patient says, “What hump?”

Q10: You hit the nail on the head with that analogy. I love the dialogues that are in your book. And I think my favorite dialogue is the second one, the choice dialogue. It is a revelation. To take the stress off the patient, to put the ball in their court, to realize you can’t force someone to have treatment done right now if they don’t want to have it done right now. Can you talk a little about the choice dialogue and its power?

PH: Mike, the choice dialogue is magic. For 10 years, I personally struggled with the question, “How much do you offer a patient?” You know, the guy comes in, he’s got a dark front tooth, he’s crying about his dark front tooth. And you say, OK, you have a dark front tooth. You put him in the chair and not only does he have a dark front tooth, but he’s got missing posterior teeth, he’s got posterior collapse, he’s got occlusal disease, periodontal disease and a couple of abscesses. But the guy is complaining about his front tooth.

How much do you offer this guy? You see, no one could ever answer that question for me. It was like you and I were talking earlier, when you said a lot of the gurus at the front of the room say to treat everyone like a right side patient. You can’t do that. Because there are a lot of people who just want to get in and out and they’re not ready for your whole song and dance. You can really alienate people by being too thorough with them.

For years, it was beat into my brain that the way to build good relationships in the dental practice is a thorough examination. And that’s true, Mike — if the patient wants an examination. But how do you build a relationship with a patient with a procedure the patient doesn’t want or isn’t ready for? And what I could never figure out is, how do you get around that? Then it became very crystal clear and very simple. Simply ask the patient what therapeutic range they are ready for today.

So, in walks a patient — his name is Kevin. I see that he’s got his dark front tooth. He tells me about his dark front tooth. He kind of grumbles about some other things going on in his mouth but isn’t too specific. I look in his mouth at the examination and I see there’s the dark front tooth. But in reality, that’s the least of his problems. He’s got problems all over the place. After my initial look, I’ll sit the chair up and this is where the choice dialogue comes in. What I will say is: “You know, Kevin, I can understand why you’re not happy with that front tooth. Boy, we see a lot of folks just like that. I want you to know today, before we do anything, that you’ve got a choice. We can focus on getting this one front tooth to look good for you, or in addition to that, would today be a good time for me to look over all your teeth and perhaps show you how you can keep your teeth healthy for a lifetime? What’s the better choice for you today?”

See, “What’s the better choice for you today” helps the dentist understand the patient’s level of readiness for full mouth care. I believe patients ultimately want full mouth care but it may not fit into their life right now. So what I want to do is select the therapeutic range most suitable for that patient today, provide it, and make the patient happy. In so doing, I have earned the right to influence this patient at another point in his life. If that patient walks out of there with that front tooth repaired and happy, chances are real strong he’s going to come back to me.

Q11: Right. And meanwhile, if you say, “Kevin, you’ve got this front tooth that’s dark, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention all this other stuff” — by throwing all the right side stuff on him without getting his permission to talk about it, you may lose him as a left side patient. Not only that, but he may go tell all his friends, “The only thing that doctor’s concerned about is money and doing all this treatment,” when in reality you just want to do what is right.

PH: Absolutely. And that’s where I said earlier that you cannot rely on your clinical skills to get you off the plateau. Because if you rely completely on your clinical skills, you look at all those conditions and then all your clinical knowledge and education starts coming out of your mouth. Just because you see that the patient has significant needs doesn’t mean you should dwell on them. And that’s called good judgment; we’re educated out of good judgment from time to time.

Q12: Exactly. I also love the advocacy dialogue, which basically has the patient dictate the pace of treatment rather than the dentist. Can you explain why the advocacy dialogue is so important?

PH: An advocate means “to guide.” Dentists have tools. We have the roles of advocate, which is the advisor. We also have the role of provider. That is actually the person who fixes the teeth. And I want you to imagine that they’re two separate roles but the same person serves each role. The advocate is the person helping you figure out how full mouth dentistry, how right side dentistry, is going to fit into your life either now or later. It’s kind of like a fee-based financial planner. You go to a fee-based financial planner and you say, “I want to build a nice, big house.” And he says: “OK, let’s look at what will need to happen here. First of all, you’re going to need to have this much money, you’re going to need to finance this much, and you’re going to need this much for a down payment. So why don’t we sell these stocks. And then why don’t we save for a year and a half until you’ve got this amount for a down payment, and then we’ll help select your contractor.” You see, what the fee-based advisor does is help you fit building this house into your life. The fee-based advisor doesn’t actually build the house — he just helps you figure out how to do it. That is one of the rules of the dentist acting as the patient’s advocate.

The advocacy dialogue is the dialogue the patient hears from the advocate as if the provider (your second role) wasn’t even in the room. And the advocate dialogue sounds like this: “I’ve done your complete exam and recognize what your needs are. I’ve gotten a sense of who you are as a person and know a little bit about your life. Based on my exam, I see you have these problems with your back teeth. I can see where this partial is giving you trouble. I want you to know that you’re in the right place; I know I can help you. What I don’t know is whether this is the right time for you to get your teeth fixed. And what I mean by that is, dentistry of this nature can be surprisingly complex and time consuming.” You might tell me you’re working on your business, you’re traveling twice a month to Europe, and you’ve got some children in college right now. And dentistry of this nature can be complicated and it can be expensive. And we need to talk about: “How do we best fit this into your life? Do we do it now? Do we do it later? Do we do it a little bit over time? Help me understand that better.” That’s the advocacy dialogue. This helps determine if we need to subordinate our dentistry to the patient’s life. It’s not about overcoming any of those objections; it’s about acknowledging objections, then finding a way to fit their dental needs into the patient’s life now or later.

For most patients, the full mouth reconstruction is not their next best step in life. Right side patients don’t get ready in the dental office. Life makes right side patients ready.

Q13: So you’ve completely de-stressed the patient at this point, they’ve got a great feeling towards you because you really are acting as an advocate. And you’re really just planting seeds, planting these right side seeds that you’re going to sow later on.

PH: And I’m not worried about this patient saying yes because I’ve got the left side of my practice paying the bills. That’s why the conversation you and I had at the beginning of this interview was so critical. You can’t have an attitude of advocacy if you’re strapped for cash as a dentist. If the lab is sending your cases COD and you’re missing payrolls, there’s no way in hell you’re going to tell a patient, “When you’re ready, I’ll be here.”

Q14: That is one of the more profound statements I have heard in a while. It reminds me of all the guys who went to cosmetic institutes back in the mid-1990s, including myself. They were being told to drop insurance from their practices. They wanted to go back and do nothing but right side veneer cases. And ultimately, most of them were disappointed. In fact, I don’t know anybody who’s got a practice like that today unless they lecture and have a very limited patient schedule. But you nailed it, you can’t truly act as an advocate when you are behind on your bills from chasing right side cases.

PH: That’s why it makes sense for those GPs to keep that healthy left side practice going and then concentrate on that right side. When I have a right side patient in my practice, I know there’s probably a 90% to 95% chance they are not going to be ready for this $10,000 treatment plan the first time they hear it. And most big cases, most $10,000-plus cases, take a year or more for that patient to get ready.

MD: It may take them a year or more to get ready, but when they are ready, there is a great chance that they’re going to come to you for that right side dentistry.

PH: Exactly. What you need is about 300 to 400 right side patients who aren’t ready but who love you and are just incubating their case. They’re saving money, they’re getting their kids through school, they’re getting through the divorce, they’re settling the lawsuit, their parents are in nursing homes. There are a million things that get in the way of a right side case. And you know what? For most patients, the full mouth reconstruction is not their next best step in life. Their next best step might be getting their kids out of college or adopting the baby or losing 50 pounds or getting married or getting divorced or settling a lawsuit or changing jobs. There are so many other bigger fish out there for patients to fry. They need to get their house in order. And it’s not about educating these patients into readiness. Right side patients don’t get ready in the dental office. Life makes right side patients ready. And when they become ready, Mike, it’s exactly what you said: There’s a 99% chance they’re going to come back to me and I’m going to be the guy fixing their teeth.

Q15: Well, of course. They like you and they have respect for you because you told them the truth but you put no pressure on them whatsoever to do their teeth now. You didn’t try to paint some doom and gloom scenario about, “If you don’t get this done in the next year or two, you may be in dentures in 10 or 15 years.” Instead of forcing them to conform to your plan of when it should be done, you’re shaping it around their life, which I think you call outside-in versus inside-out. But one of the things that I like, at the very end, after you’ve even done the financial option dialogue, is when you finally have the technical dialogue, the technical case presentation. And I think that’s so great, how you really flip this on its head. The very last thing that you do with the patient once everything else is in place is to tell them this is actually what you’re going to be doing. Traditionally, don’t dentists put this way towards the front of this whole process?

PH: Dentists get into the “How we’re going to do it” conversation first. They’ll say, “Well, the first thing we’re going to do is treat the perio, then we’re going to do the endo, then we’re going to do this one, then we’re going to do that.” And when they get done telling you how they’re going to do the case, the alternatives to this could be this, this and this. And the reason we’re choosing this over that…what happens is the conversation gets so complex, the dentist forgets what the patient’s disability was to begin with. What makes much better sense is to deal with the case simply, letting the patient know the expected outcomes. But all of the detail in form and consent conversation occurs after the patient understands the outcomes and the finances and is ready to move forward. It’s so much easier to do it like that.

Q16: You know there’s a fascinating quote in your book. In fact, I listened to the CDs in my car and then went back and read the book because I was so fascinated with the concepts that you wrote here. And one of the things that really stuck with me — you have a quote from Daniel Goldman. And the quote, which I’ve probably thought of on a daily basis since I’ve read it, is, “Lack of emotional intelligence makes smart people look stupid.” If you can, I’d like you to talk a little bit about how that applies to dentists and our interactions with patients and staff.

PH: Dentists suffer from what I call the accidental education. The intentional education in dental school was that we learned the skills and the art and the science of dentistry. The accidental education is while we were learning the skills and the art, we learned a very linear, very cognitive centered communication style. We learned to talk in terms of facts, figures, data, proof and outcome. The problem is dental patients, by and large, aren’t equipped to totally understand that level of cognitive dialogue. Our language is loaded with jargon and really centers on: “Here is the condition in your mouth, here is how we’re going to fix it.” That’s very lifeless; it really lacks stimulation. Whereas the right side patient needs to have a conversation that sounds like this: “Mike, I understand what your disability is. I want you to know that you’re in the right place for us to relieve it. How do we best fit this dentistry into your life?” That’s the conversation.

Now, this latter conversation I just discussed with you doesn’t have a large clinical component in it. It has a very large emotional component. And when I say emotional, don’t diminish the word emotional as being noncognitive. Emotional intelligence is just another way of being smart and we need to wise up. Patients don’t accept treatment plans based on our ability to educate them. Patients accept treatment plans based on our ability to understand how to gauge the fit into their life, either now but mostly later.

I have surveyed literally tens of thousands of dentists in seminars. I had such a struggle with a meeting two years ago — I had 900 people in the room; I asked this group: “I want you to imagine if you had 100 consecutive $10,000 new patients you examined and treatment planned. One hundred $10,000 new cases. What percentage of them will start immediately?” Do you know what the typical answer is, Mike? Fewer than 5%. So 95% of the time, the right side isn’t ready. Well, if that’s the case, then we need to adopt an attitude that creates a case acceptance system catering to people who aren’t ready.

How do you do that? The way you do that is by not making case acceptance a condition of a good continuing relationship with them. In other words, we need to drop all this language about, “I’m not supervising your neglect.” We need drop the diminishing language that treats the patients like idiots. How many times do you need to tell a patient on a recall visit they need a bridge? When they hear it the third time, they get it! It isn’t that they don’t want it, it’s just that it doesn’t fit into their life. We don’t have the communication, we don’t have the cultural vocabulary to talk to people about how dentistry fits into their life, we just talk about how it fits into their mouth.

Q17: And you know, right side patients, they’re right sided for a reason. Part of it may be money, maybe fear, but it seems they’re right sided for a reason. Because they have a phobia, they have something that allowed them to get this condition, this right side condition that they’re in now. It very well may be that they’ve never trusted any of the dentists who’ve they met before. So to be able to act, as you’re saying, as an advocate is fantastic. I think there’s a quote in your book that says, “You cannot educate a patient to readiness.” And the one that I really like is, “Right side patients need hope more than they need patient education.”

PH: That’s right. You know, it’s not always neglect. Consider the people that I grew up with, my mom and dad, my aunts and uncles. We grew up blue collar in suburban Chicago. Nobody had any money. And, you know, if you had a bad tooth, my mom would have it pulled. But it wasn’t that she was stupid, it was that there was only so much money to go around. And a lot of times, people make huge sacrifices for their children, for their family. And the kids grow up, they move away, and now she’s 55 years old and she says: “You know what? It’s time for me.” And it doesn’t mean that she’s been a bad person; it just means she’s had some cards dealt that people who are more fortunate maybe haven’t had.

Q18: Right. But I think a lot of us have also seen the right side patients that do have the money and still don’t want to do it, and maybe will never do it. But it’s still nice to keep them as left side patients. I think it’s really difficult to evaluate your own case presentation skills without having someone there to watch it. Or even to see it outside of dentistry. And one of the things I like in your book is you take the dentists verbal skills and apply it to, “What would it look like if a dentist sold real estate?” Can you talk a little bit about that?

PH: If we take the dental sales model of, I call it the inside-out model — that is, we focus on the inside-the-mouth issues first, the examination, the diagnosis and treatment plan. We focus there, we spend all our time and assets on that. Then we put together a treatment plan. We present it to the patient. Now the patient hears the words “five thousand dollars.” We discover what’s on the outside of the patient’s mouth. The outside of the patient’s mouth is the patient’s budget, their schedule, their hobbies and family life. So we use an inside-out approach focusing on the inside-the-mouth issues, we quote the fee, and that’s when we accidentally discover what’s going on outside of the patient’s mouth.

Now the inside-out approach works pretty well on the left side. Why? Because the outside of the mouth issues for a left side patient usually aren’t deal breakers. I mean, if it’s a $1,200 case, insurance is going to pick up half of it, their credit card can pick up the other half. Plus, a $1,200 case, what is it going to take you? Two, maybe three appointments max. Not a lot of interfering issues occurring with a left side patient.

What if the case was $12,000? Well, now, how much does a $12,000 budget impact a case? For most people it impacts it a lot. Plus, a $12,000 case is going to take several appointments or a couple months, and that may be a deal breaker or something that gets in the way for a lot of people. So, what we need to do is kind of figure out what’s going on outside the patient’s mouth prior to spending a lot of time figuring out what’s going on inside the patient’s mouth. A left side patient would do real well with an inside-out approach. But a right side patient, we need to spend some time with an outside-in approach; find out what’s suitable for the patient.

This is where I make the comparison: What if a dentist sold real estate? See, if you and your wife are going to buy a new home you go to a real estate agent. That real estate agent is going to ask you the price range, right? See, because the price isn’t inside the house, the price is outside the house. The next thing she’s going to ask you is the amount of down payment you can afford. The down payment isn’t in the house — the down payment is in the bank, not inside the house. The next thing she’s going to ask you is what neighborhood you want to live in, yet the neighborhood is not in the house. A good realtor will settle all of the outside the house issues first before they show you the house. Why do they do this? To make sure the house they show you is suitable.

Suitability and affordability are built into the language and culture of the real estate agent. Dentistry does not have suitability built into its language; dentistry just focuses on clinical quality. And we haven’t had the cultural permission to determine patients’ budgets. No one teaches you how to determine patients’ budgets. My God, it almost sounds like heresy. So if you go to a realtor who is a former dentist, you would expect an inside-out approach. You would say, “We’d like to buy a house!” And the dentist, because he’s focused on quality, says: “Well, the most important aspect of this house is the foundation. Now there are three different types of foundation. There’s cement slab, four-foot crawl space, and there’s full basement. Now the best basements have poured, concrete cement blocks and there are six different types of cement blocks and three different types of cement block joints. Here’s a photomicrograph of the cement block joint.” And then he’s going to educate you on bricks. Then he’s going to say to you, “Now, before you make any decision on your house, I want you to see our brick layer.” Now, what would you think?

MD: He’s crazy.

PH: He’s crazy. You’d think about finding another dentist. And when the buyers walk out of this dentist’s real estate office, the realtor dentist would say: “Ha, those people have low house IQ. I’m going to take a course in carpentry so I can sell homes better.”

MD: Because many dentists think that taking every CE course on the planet is the answer for how to do right side cases.

PH: That is the cultural blind spot, Mike, right there. Culture is shared belief, shared language, shared behavior. And dentistry is a culture. And at the center of our culture is clinical excellence. Gosh, people sacrifice their careers to produce the perfect restoration. And consequentially, because clinical excellence is at the center of this, we believe that the more we can do to produce it the more successful we’ll be. That’s not true.

Q19: That’s absolutely not true, but it’s so much easier to go take a course for four days than it is change the way that we think and talk to patients. It’s such a less painful route to go, isn’t it?

PH: It is. It’s only painful in our culture. I do a lot of work within the financial services market with financial planners. I also work within the legal industry and with CEOs of sales forces. The industry of dentistry, culturally, is very interesting in that we continually make the same mistake time and time again. Because, culturally, no one has given us permission to talk to the patient about their budget. No one has given us permission or given us the literature or given us the skills to talk to someone about a simple thing like: “Maybe now is not the right time for you to get your teeth fixed.” I mean, that is a perfectly logical statement coming from a financial planner talking to someone about building a house. I could say: “Mike, maybe now’s not the time for you and your spouse to build this house. Why don’t we wait until two or three years from now when you have more cash for a down payment and we can get you a better loan rate.”

MD: I think part of that comes from the fact of the use of the word “doctor.” You know, when you put “doctor” in front of something I think there’s maybe an assumption on the part of a lot of dentists that we’re supposed to be above all that stuff.

Gosh, people sacrifice their careers to produce the perfect restoration. And consequentially, because clinical excellence is at the center of this, we believe that the more we can do to produce it the more successful we’ll be. That’s not true.

PH: We’re below all that. You know, there’s nothing dishonorable about helping someone make a good decision.

Q20: In a perfect world, would you see this system being taught in dental school prior to any clinical education?

PH: No, I think dental students have enough eggs to fry without this one. I think dental schools should focus on how to fix teeth, how to understand the biology and the biomechanics and all that. I remember my dental school experience — it was pretty tough. Dental students need to know how to pass the state board. Then they become open to learning something else, you know what I’m saying? And my experience with young dentists is many of them need to kind of hit this plateau before they’re ready to grow, to tell you the truth. So, I don’t know if I’d put it in place that early.

You know, I certainly make my books and audiotapes available to students. But as far as how to talk to people? Dentists need to solve a lot of personal issues related to their own confidence and competence before a lot of this becomes real for them. My experience has been that once they learn their way around the mouth a little bit, then they become much more ready as students.

MD: That’s true. When dentists walk through our lab and they see full mouth cases being prepped and the preps aren’t as good as theirs, I think they wonder, “Why is a dentist with less clinical skills than me able to do these full arch cases?” It’s got nothing to do with clinical skill, that’s why!

PH: That’s right!

MD: That’s where a system like yours can really come in handy, and I’m certainly going to recommend this to our readers. To not only read the book or listen to the tapes, but to attend your courses as well when they get a chance. Because this is really some stuff that turns what we’ve traditionally done on its ear, and really takes the patient’s point of view into account. So, I want to thank you, Paul, for spending some time with us, and passing along all your valuable knowledge to our readers.

PH: It was my pleasure. Thanks for the opportunity, Mike.

Paul Homoly can be reached at 800-294-9370, paulhomoly.com or by email at paul@paulhomoly.com.