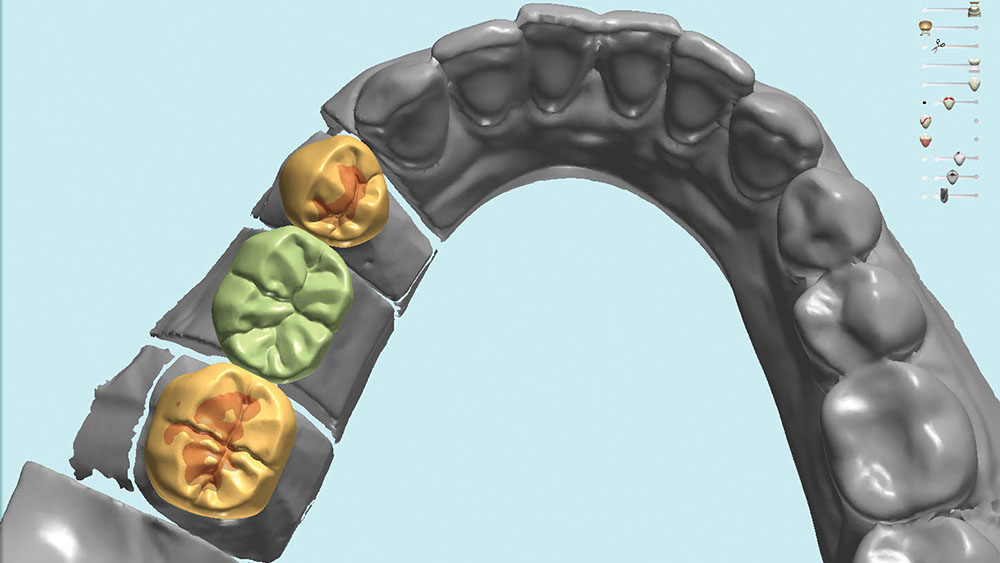

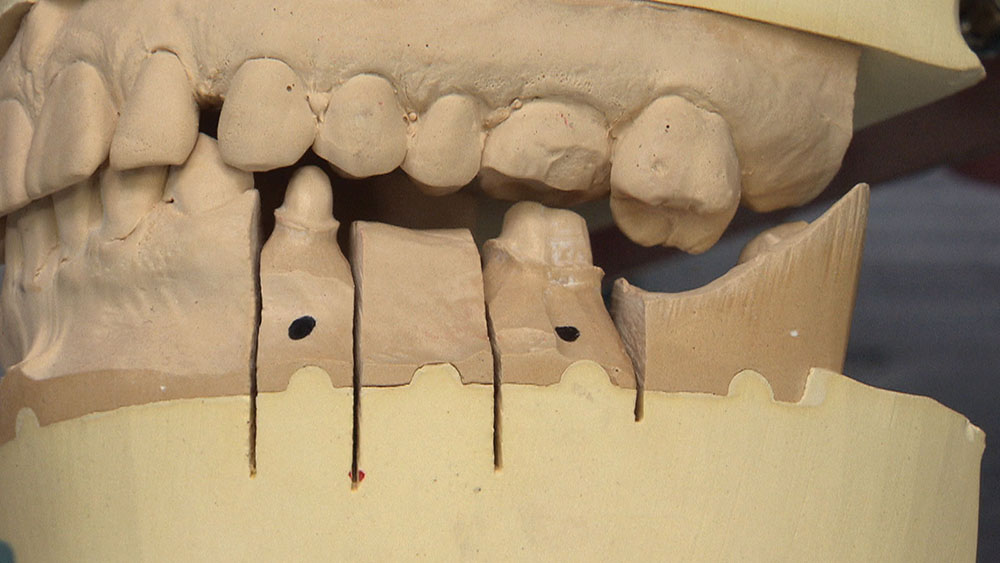

No BruxZir® Bridge for You! Case of the Week: Episode 92

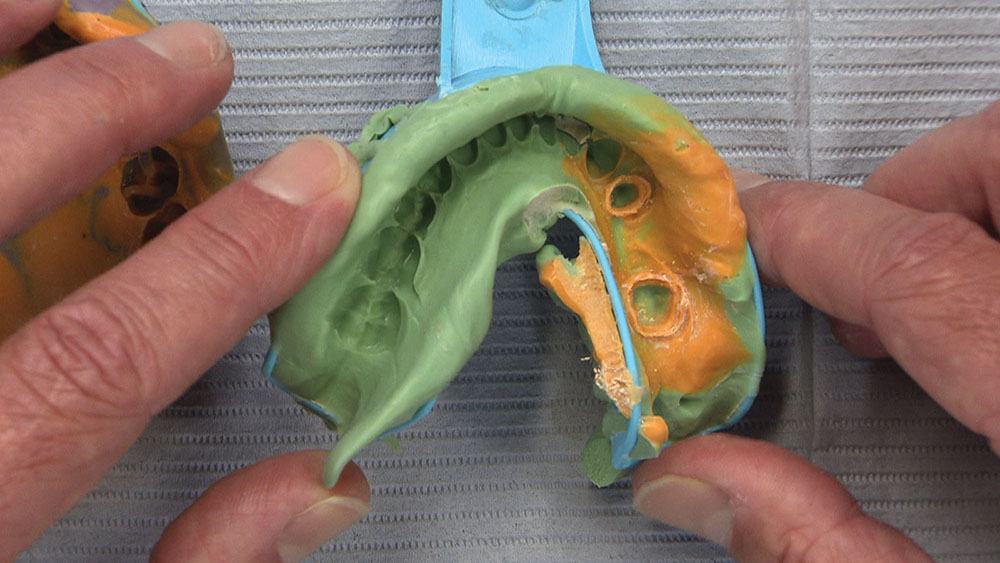

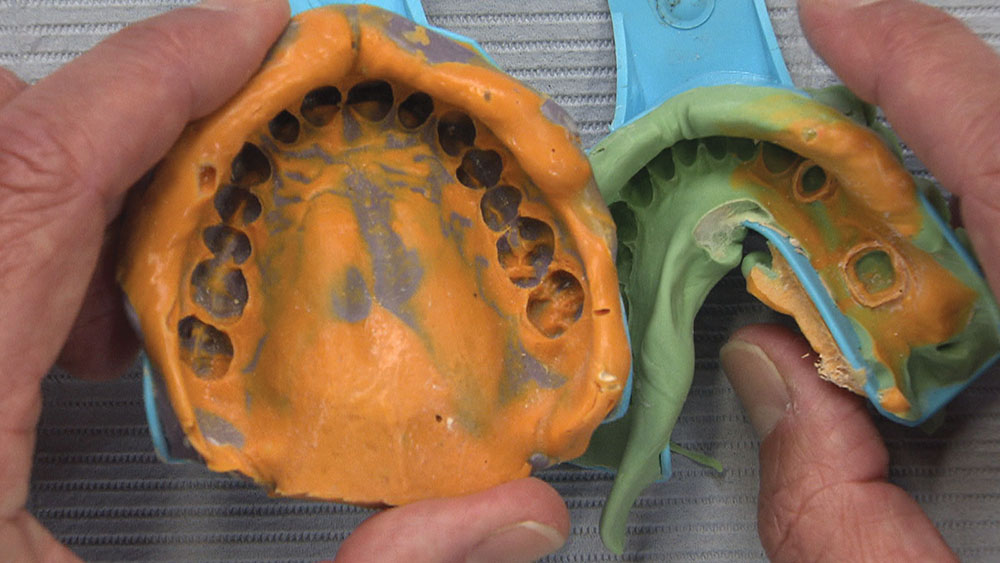

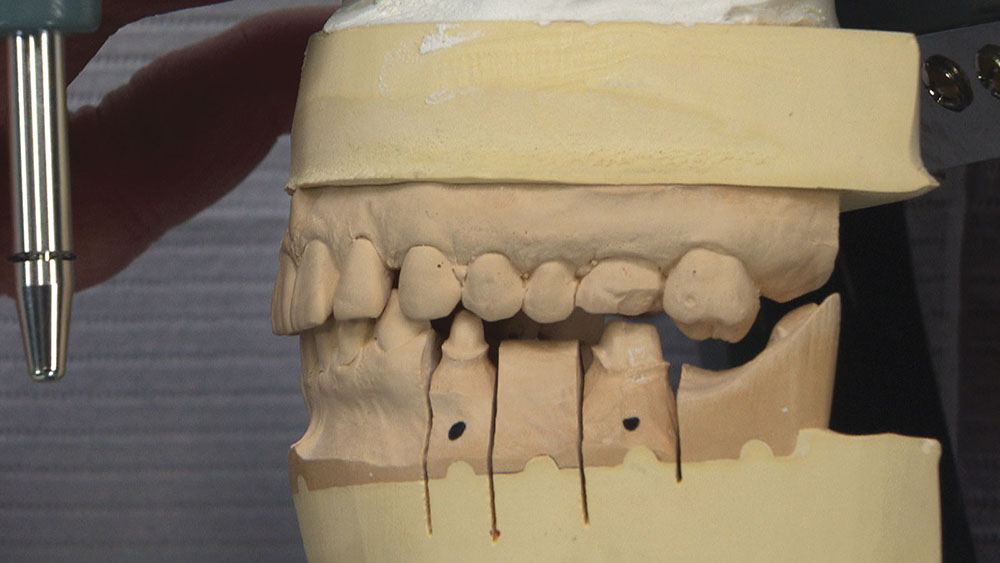

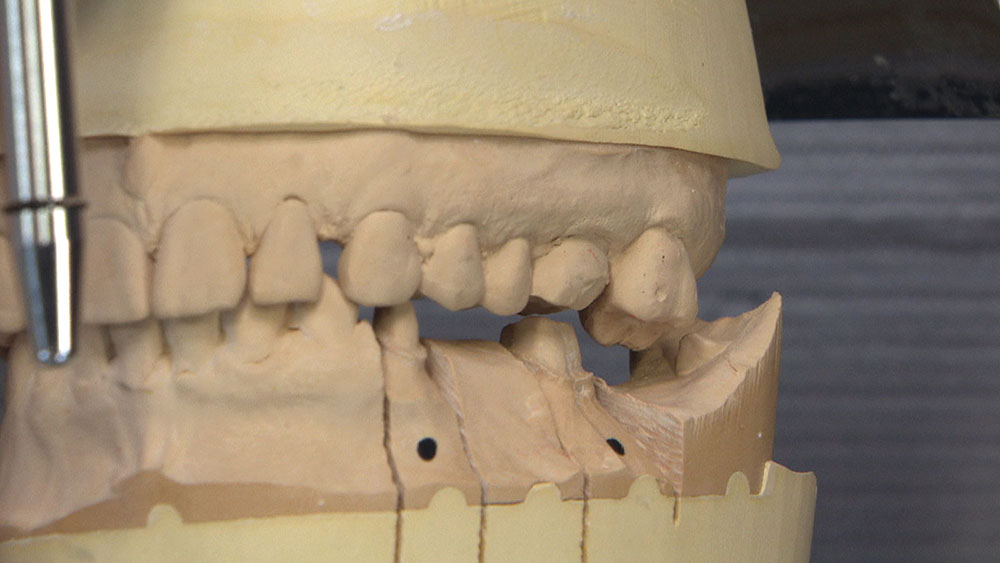

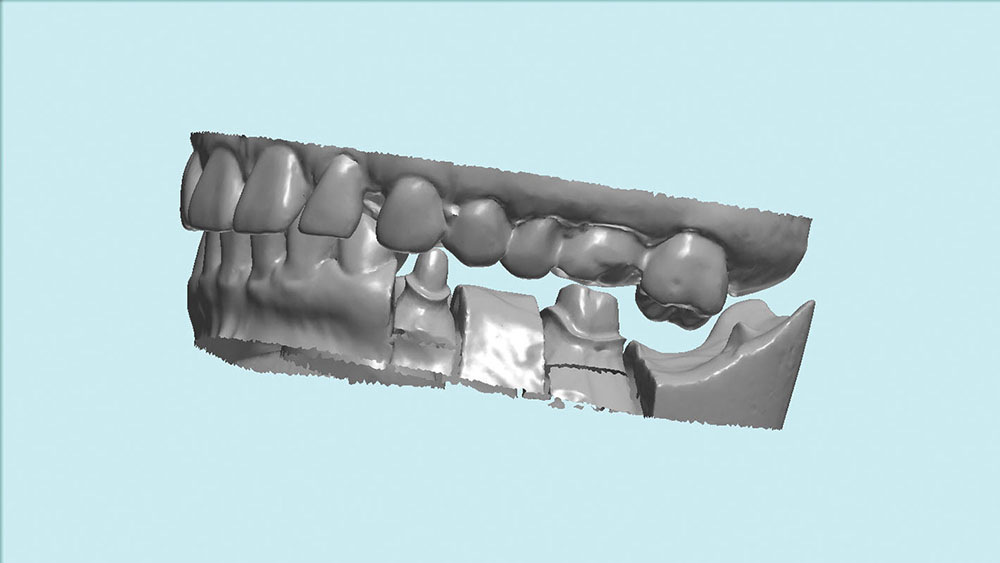

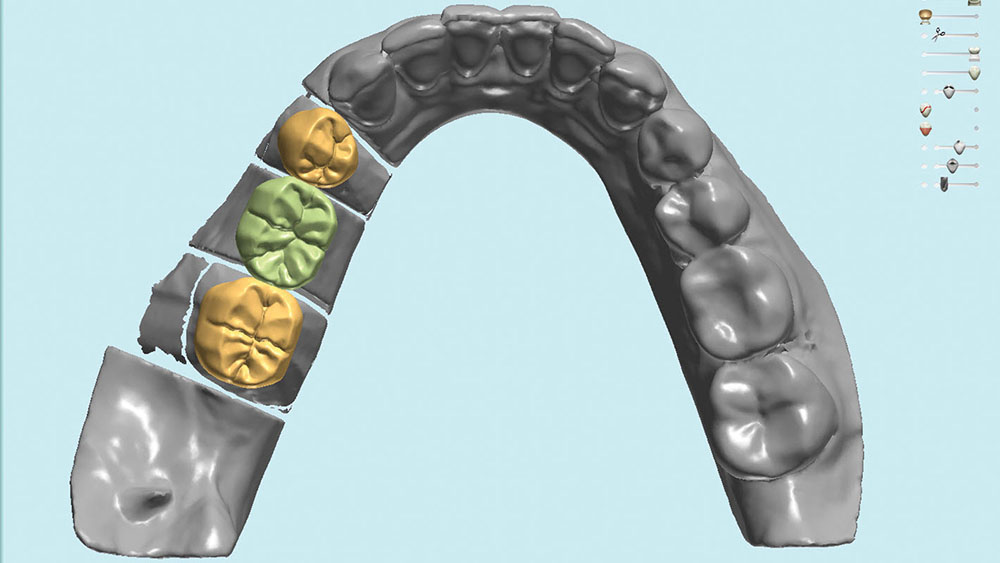

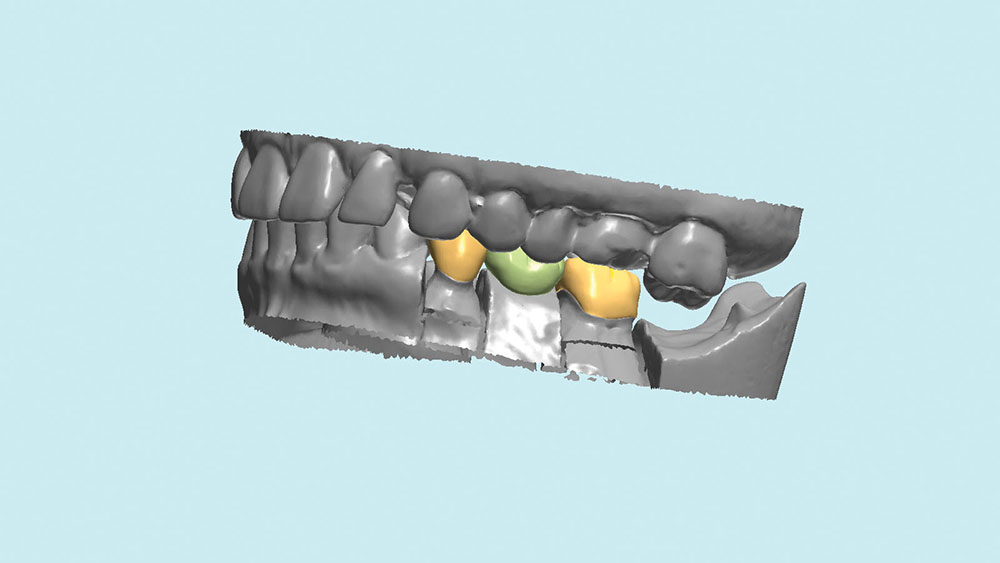

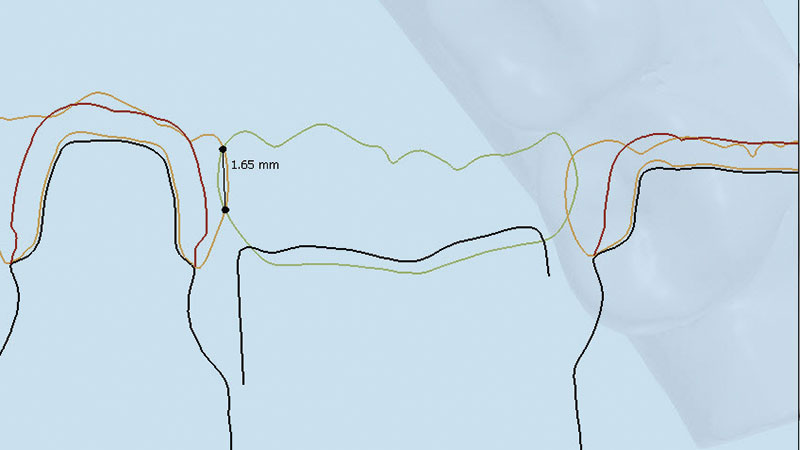

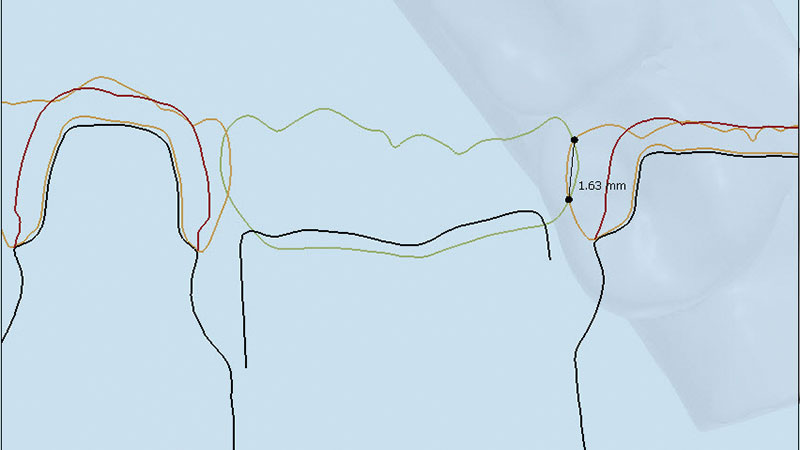

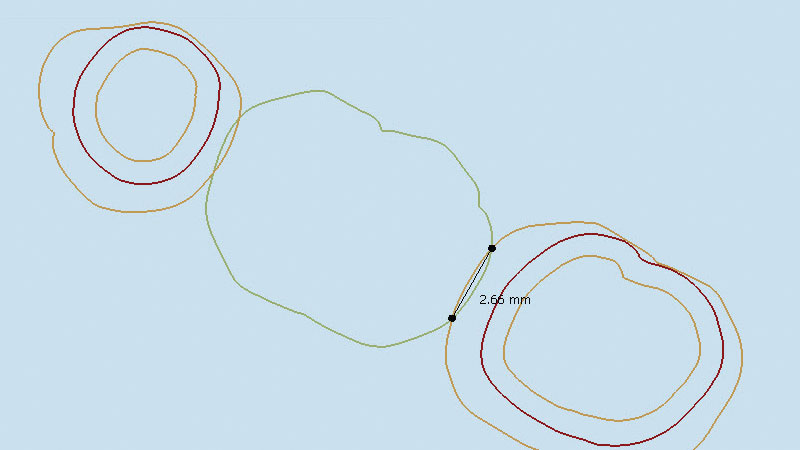

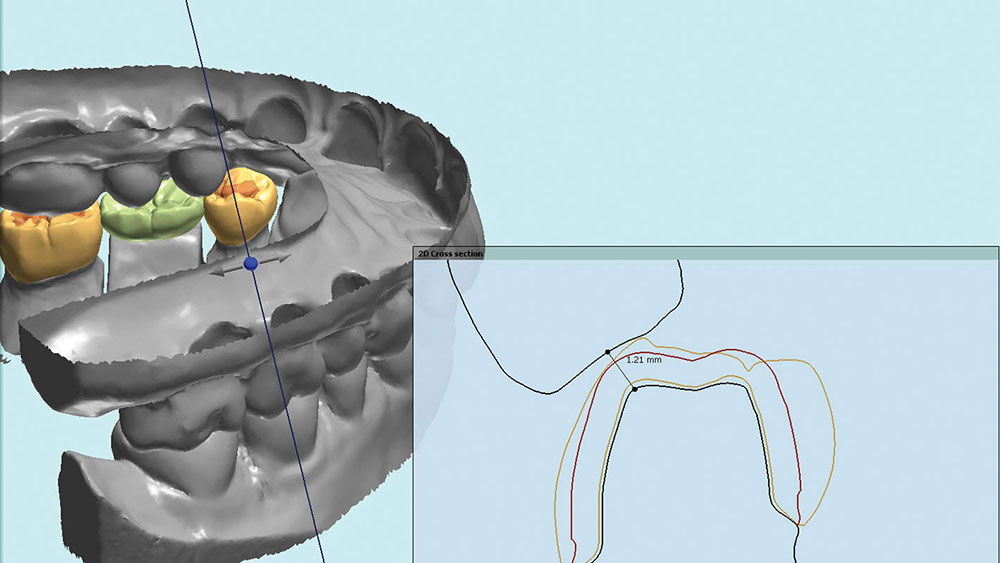

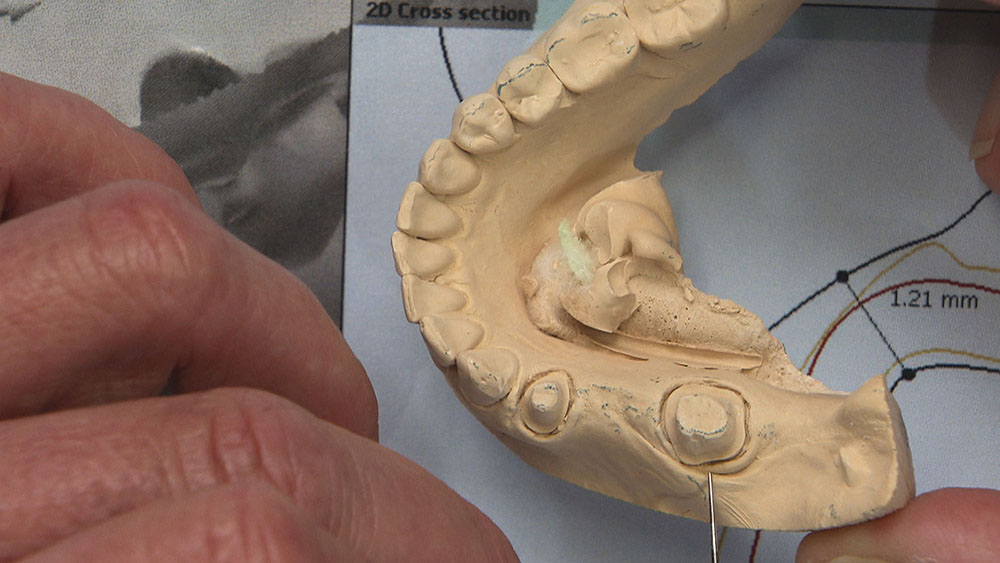

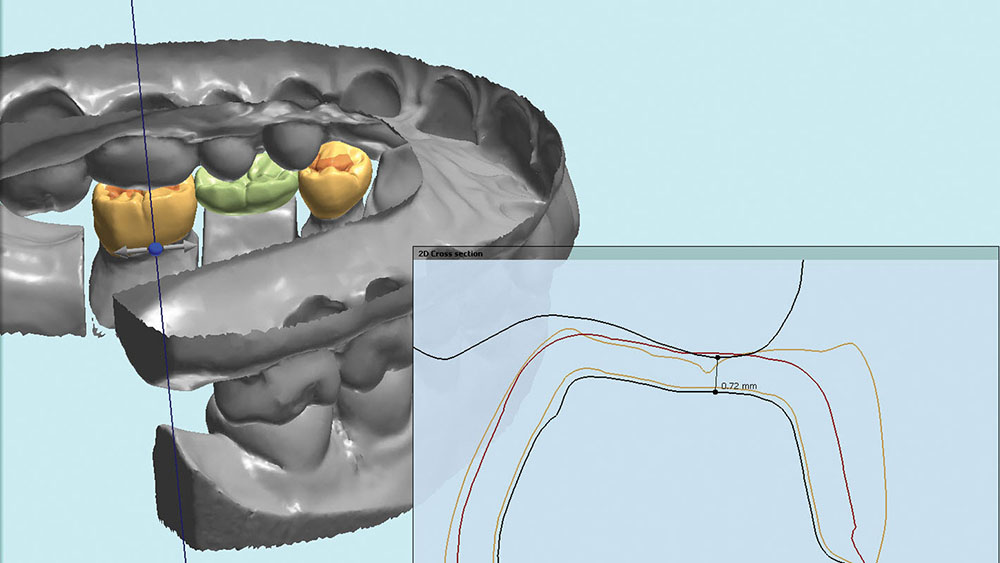

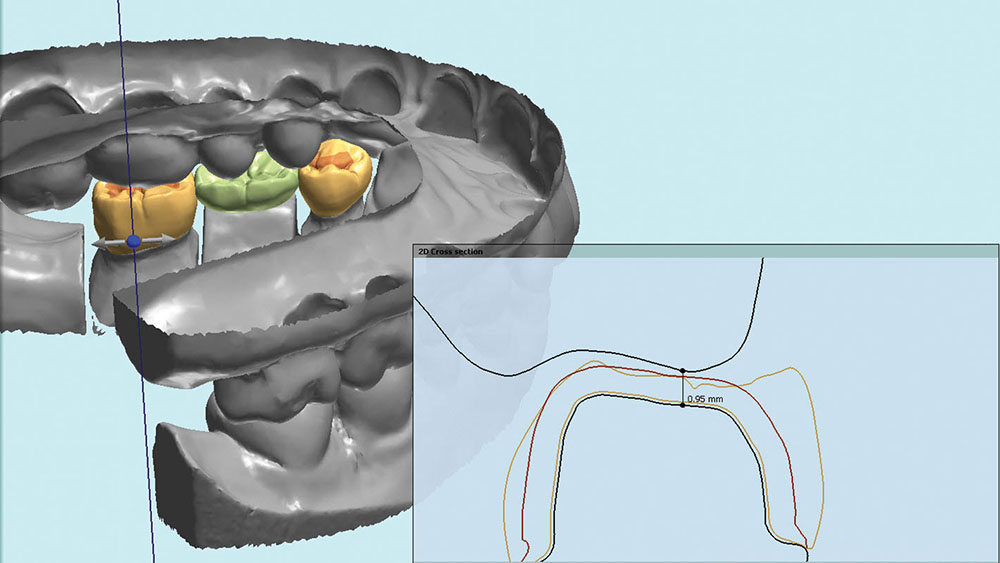

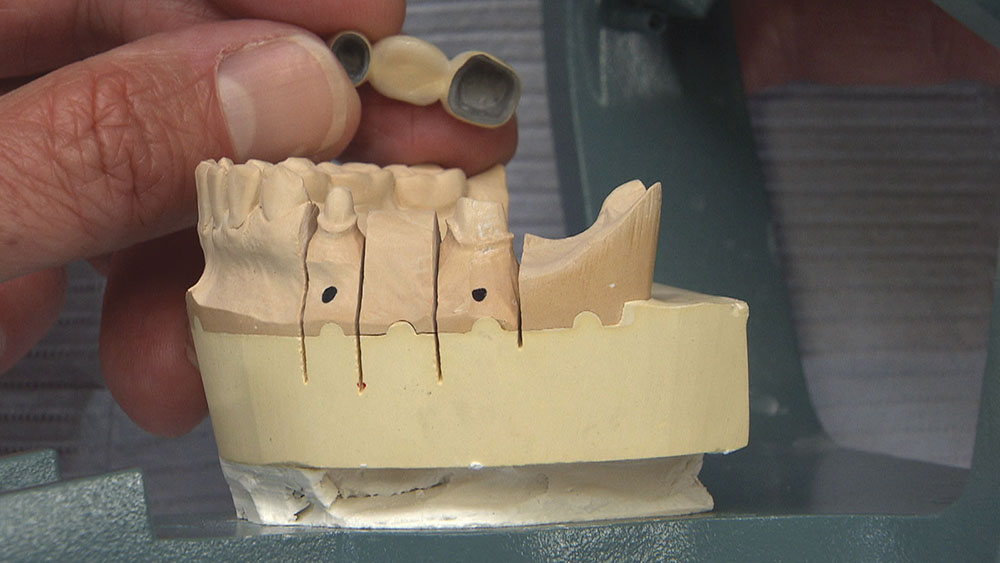

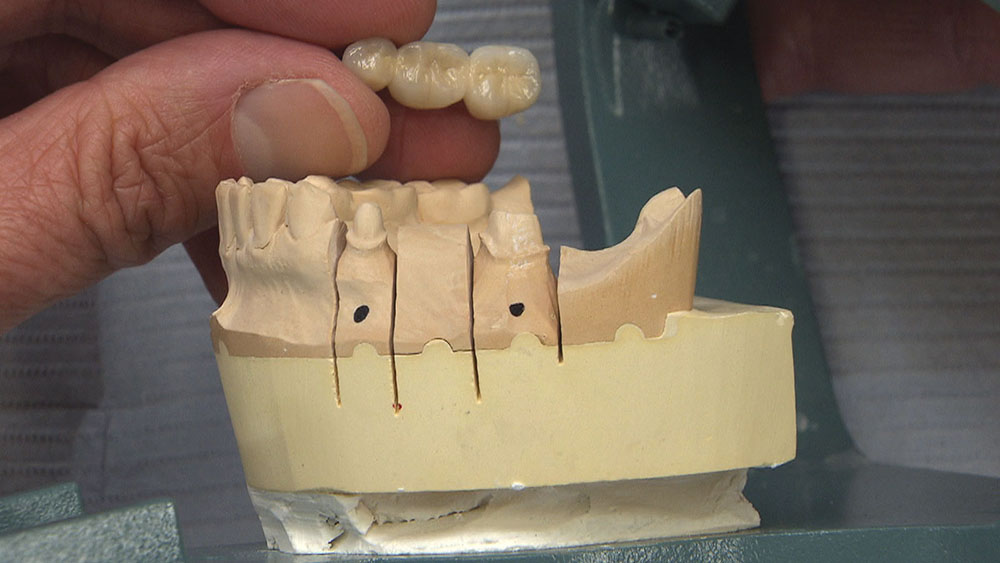

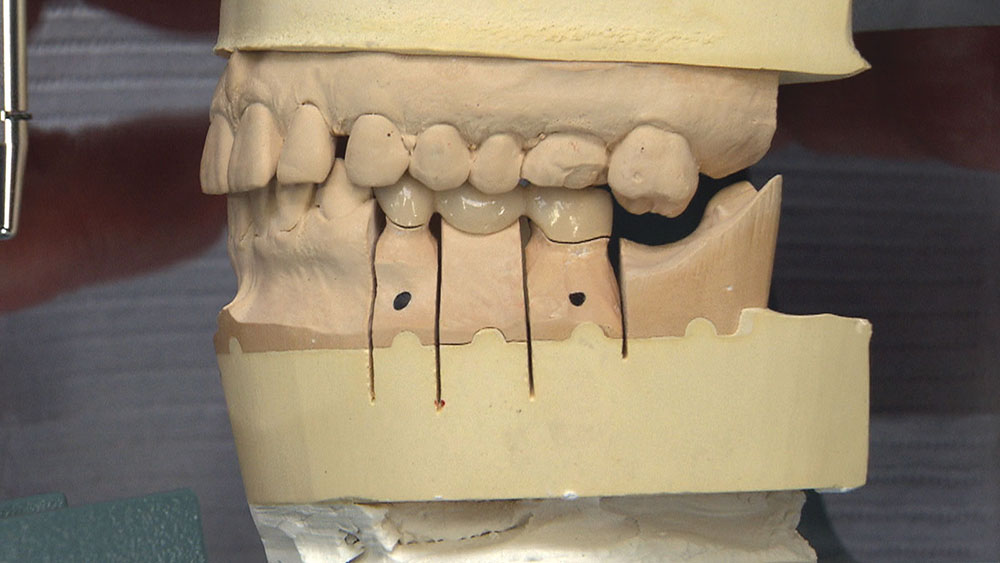

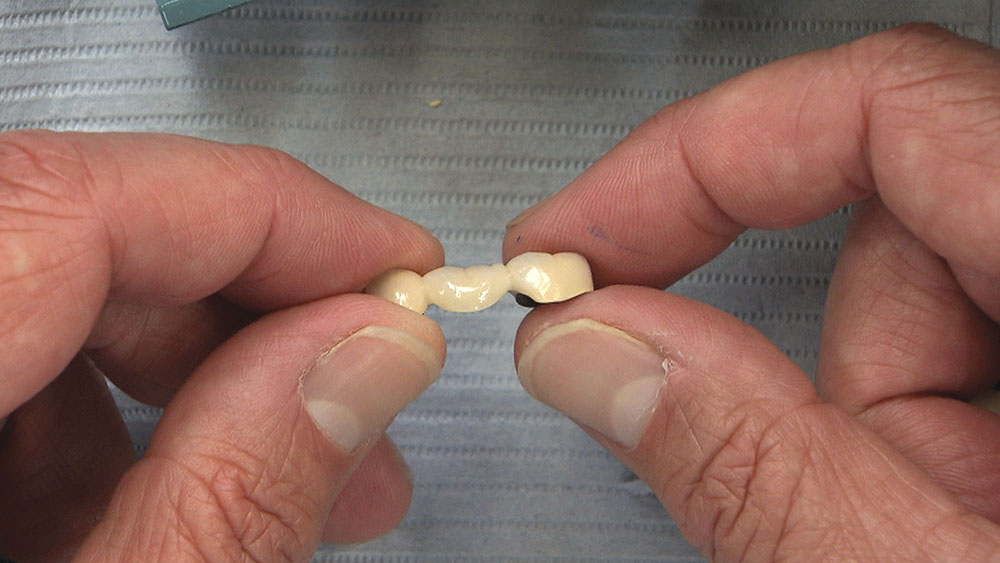

The video stills that follow highlight an interesting Case of the Week from Episode 92 of "Chairside Live," featuring a fractured PFM bridge. The dentist sent it in with a request for an all-ceramic BruxZir® Solid Zirconia bridge (Glidewell Laboratories; Newport Beach, Calif.) as a replacement. While BruxZir Solid Zirconia is often a viable choice for these high-strength, multi-unit posterior cases, this particular case illustrates why a technician might sometimes determine otherwise.