Making Better Decisions

Each day, we are presented with a series of situations that require us to make decisions. Some decisions are trivial — “What clothing should I wear?” or “What should I eat for breakfast?” But others can be important and lifechanging — “Who should I hire?” or “How should I invest my retirement funds?” In most of these cases, we have neither the time nor the inclination to gather all of the facts needed to make a perfectly informed decision. In response, we develop a set of mental shortcuts called “heuristics” to shorten the decision-making process. This process is often called common sense, intuition, a rule of thumb or a gut feeling, but it is actually a set of mental shortcuts we use to make decisions based on our existing knowledge and experience when we are lacking the full set of information required for a fully rational decision.

For example, when the time comes to purchase a new car, there is voluminous data available related to performance, maintenance, initial cost and resale value. Most of us will read a few reviews, stop in at a few dealerships, then select a car based on our overall evaluation of this partial information. Often, our gut feeling — the brand’s prestige, the car’s appearance or a friend’s experience with the car — plays a decisive role. Perhaps we employ a “rule of thumb” and always buy the car rated best by Consumer Reports.

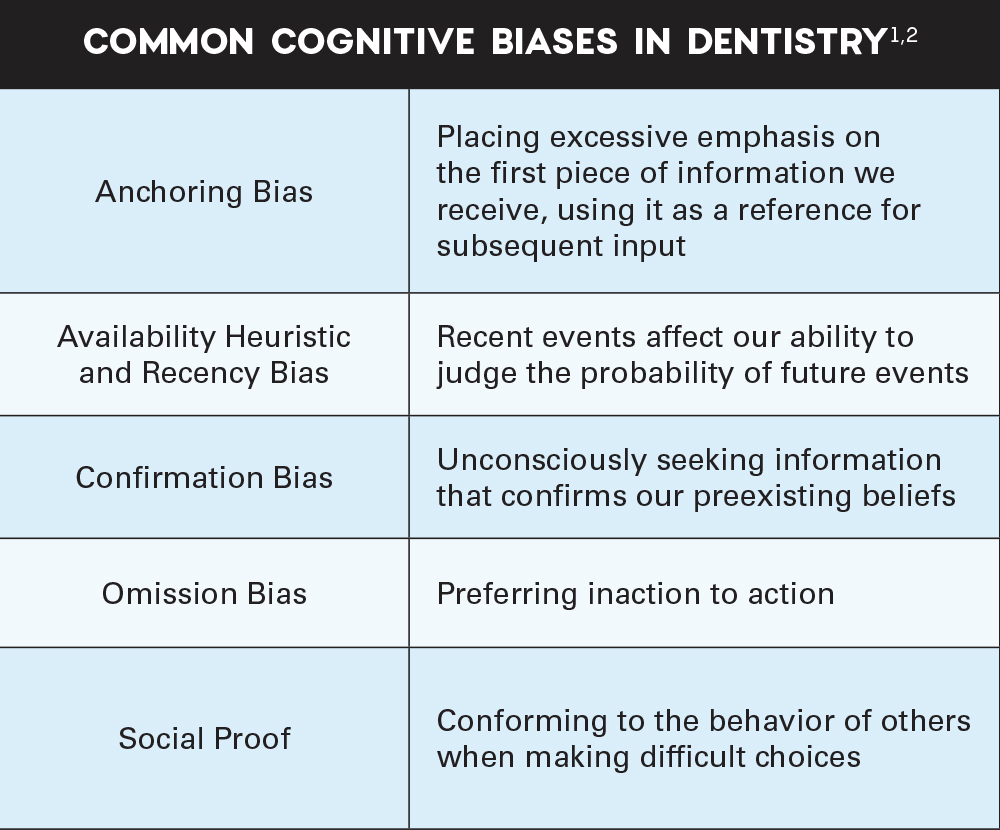

It’s important to understand that because our decisions are influenced by many factors beyond a pure analysis of the facts, these shortcuts can lead us to make errors in our decision-making process. The thinking process that we use in these shortcuts results in cognitive biases — the ways that the context and framing of information leads us to systematic and predictable patterns where we deviate from the rational decision.

For example, when purchasing a new refrigerator, we are offered the opportunity to add a service contract. Since we usually are buying a new refrigerator because our old refrigerator recently broke down, the Availability Heuristic and the Recency Bias might lead us to believe that the likelihood for needing repairs is much greater than it actually is, and we would lean toward purchasing this service contract. The Loss Aversion Bias, where we feel the pain of losses more strongly than the pleasure of gains, would lead us in that same direction. Unfortunately for our checkbooks, rational analysis of the data regarding frequency of repair and overall costs would show that the purchase of this service contract is a poor investment. Our cognitive biases have led us to an irrational decision.

Understanding these cognitive biases — and knowing how they influence our decisions — can help us make better decisions as leaders, businesspeople and clinicians. They can also help us understand how to influence our coworkers and patients to make more beneficial choices.

The ability to communicate with our patients and help them make the best oral health decisions is the most important skill in clinical dentistry. Let’s look at some practical examples of how cognitive biases can influence dentists and patients.

DIAGNOSIS

Confirmation Bias is a well-known and well-documented source of diagnostic errors. This principle says that we unconsciously seek out — and place more emphasis on — information that confirms our preexisting beliefs than we do for information that might disprove them. For example, if a patient complains of pain in the area of a tooth with an old alloy restoration, we might assume that this suspicious tooth is causing the patient’s discomfort. We might not perform an intraoral or radiographic examination of other teeth that could be causing the discomfort. Focusing on the suspect tooth, we tap, perform vitality testing, and examine the occlusion on that tooth and may neglect to look at others in the region that could be causing the patient’s discomfort. We look for diagnostic evidence that aligns with our initial impression, sometimes overlooking alternative diagnoses.

PRESENTING TREATMENT PLANS

The Anchoring Bias occurs when we place an inordinate amount of emphasis on the first piece of information we receive. We tend to compare subsequent data to that initial information, which influences our decision. For example, when presenting treatment options and the associated fees, if we present a higher cost option first, then offer a more moderately priced treatment plan, the Anchoring Bias will cause the patient to see the second fee as more affordable. They are using that first fee as the anchor and comparing subsequent treatment plans to that cost.

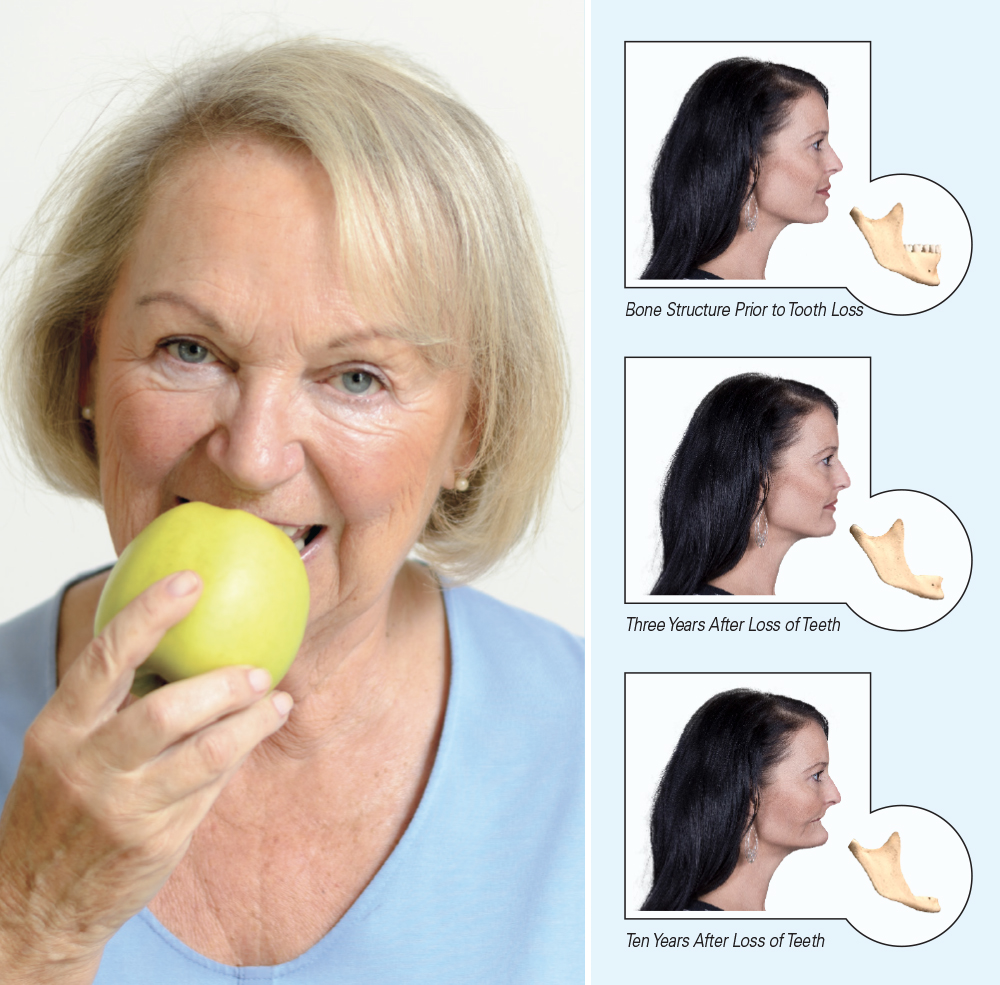

Loss Aversion Bias says that we are more highly motivated to avoid a loss than to acquire an equivalent gain. In fact, it has been shown experimentally that we experience the negative effect of losses with twice the intensity that we feel joy from a similar gain.3 This tells us that while many of us focus our treatment planning discussion on the benefits of the proposed treatment, it may actually be more effective to spend time discussing the consequences of failing to treat the situation. For example, when discussing the recommendation of an implant supported restoration for an edentulous patient, make sure that the patient understands how tooth loss leads to bone loss, which leads to an aging appearance and a diminished ability to chew a healthy variety of foods. This will lead the patient to place greater value on your treatment recommendations than focusing on the esthetic and functional benefits of the restoration. Remember that patients are more disposed to spend money to avoid a loss than to gain a benefit.

MARKETING

Social Proof is a cognitive bias that leads people to look to others for cues to make their decisions. This bias is the foundation for the popularity of testimonials and the effectiveness of social media. Knowing that others — particularly others in their socioeconomic group — have been pleased with implant treatment or esthetic restorations predisposes the patient toward treatment acceptance. This bias confirms the validity of social media posts showing happy patients expressing their pleasure with your treatment. Using patients with a variety of ages, genders and ethnicities offers a greater opportunity for prospective patients to identify with one of your happy endorsements.

CONCLUSION

Cognitive biases can help us make decisions but can also lead to faulty interpretations of the facts. Understanding these biases can add greatly to our skills in treatment planning, patient communication and practice leadership.

References

-

Nortje A. What is cognitive bias? 7 examples & resources [Internet]. PositivePsychology.com. 2020 [cited 2024 Feb 5]. Available from: https://positivepsychology.com/cognitive-biases/.

-

Cognitive Biases [Internet]. Conceptually. [cited 2024 Feb 5]. Available from: https://conceptually.org/concepts/cognitive-biases.

-

Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. The Econometric Society. 1979;47(2):263-392.