Using Technology to Improve Patient Communication and Case Acceptance

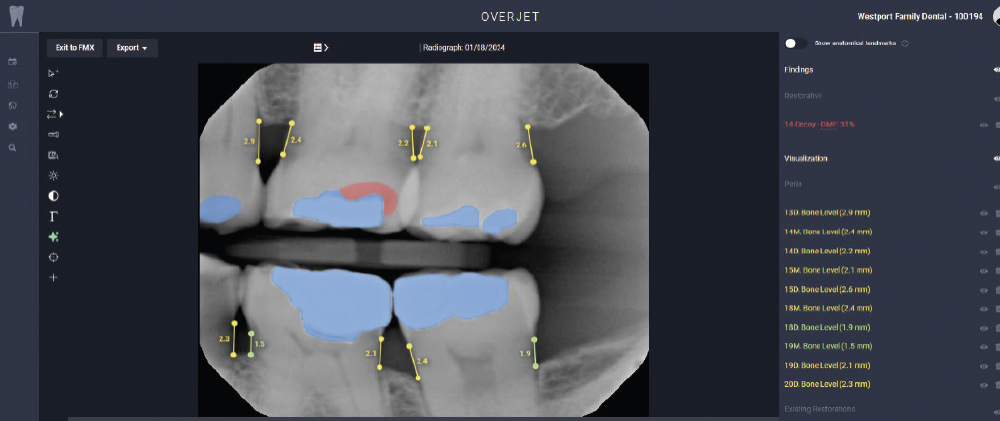

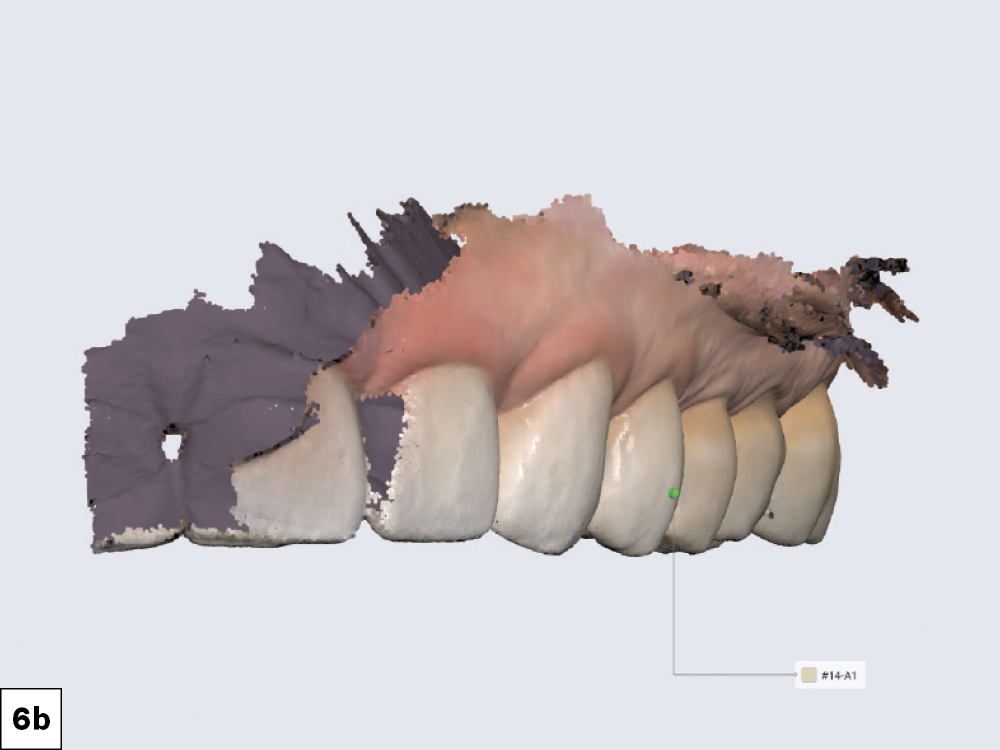

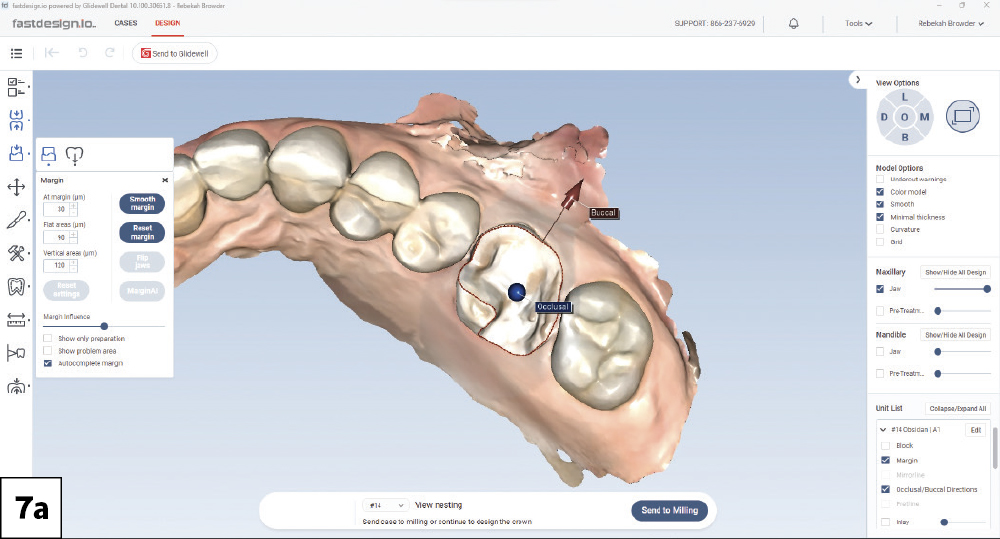

Recently, when a patient came in for a “filling” that ended up requiring more extensive treatment, I was reminded of why digital technology is an invaluable tool for improving communication. By explaining my decisions at every step, I was able to give this patient an objective view of my treatment plan and guide her toward making an investment in her oral health.

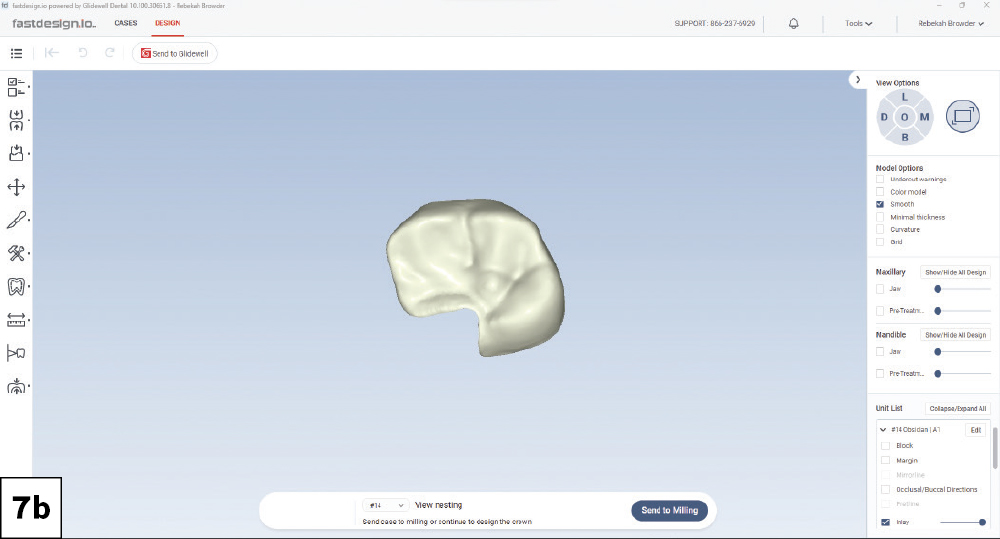

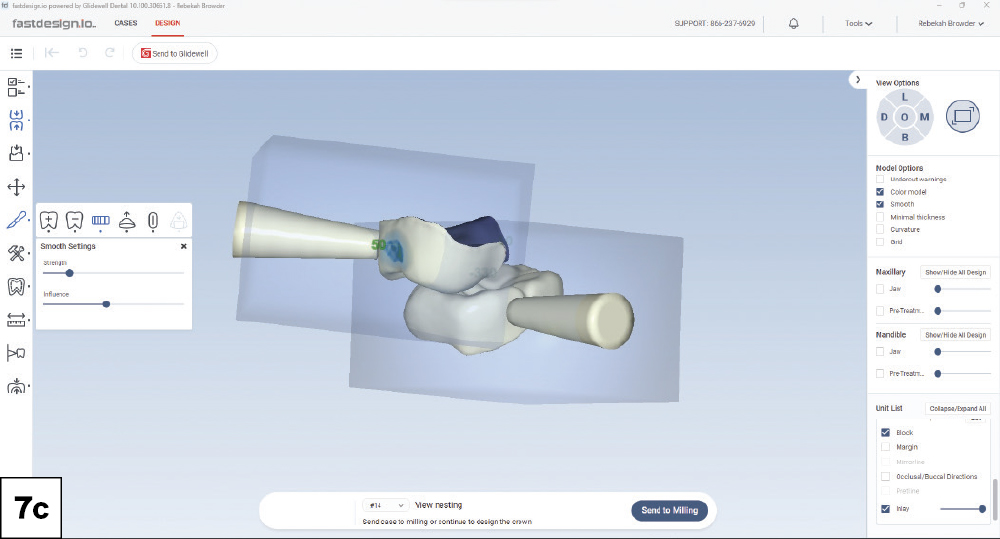

CASE REPORT

CONCLUSION

Digital tools play a crucial part in empowering patients to take an active role in their treatment and enhancing their understanding of clinical recommendations. By presenting them with an objective view, patients are more likely to accept treatment and leave my office knowing that they made a great investment in their oral health.