Simplifying Digital Scanning for Full-Arch Implant Restorations (1 CEU)

Digital dentistry has revolutionized how clinicians diagnose, plan and restore implant-supported reconstructions. Among these innovations, All-on-X implant-supported restorations have become one of the most predictable and transformative solutions for restoring edentulous arches — enhancing both function and esthetics, while improving patients’ quality of life.

As technology continues to advance, both surgical and restorative workflows are becoming faster, more precise, and more efficient. One of the most significant areas of growth is intraoral scanning. With advances in image acquisition, data processing, and design integration, intraoral scanning is now a central tool in the modern digital workflow.

While intraoral scanning has proven to be highly accurate for single units and short-span restorations, some clinicians may find full-arch implant impressions more challenging. Capturing multiple implant positions across an edentulous arch introduces variables that can lead to distortions, stitching errors, and loss of precision.

This article reviews some of the principle factors that affect the accuracy of full-arch intraoral scans in implant dentistry, examines the clinical implications of these challenges, and highlights one specific scanning system that has simplified full-arch implant prosthodontics.

INTRAORAL SCANNING IN IMPLANT DENTISTRY

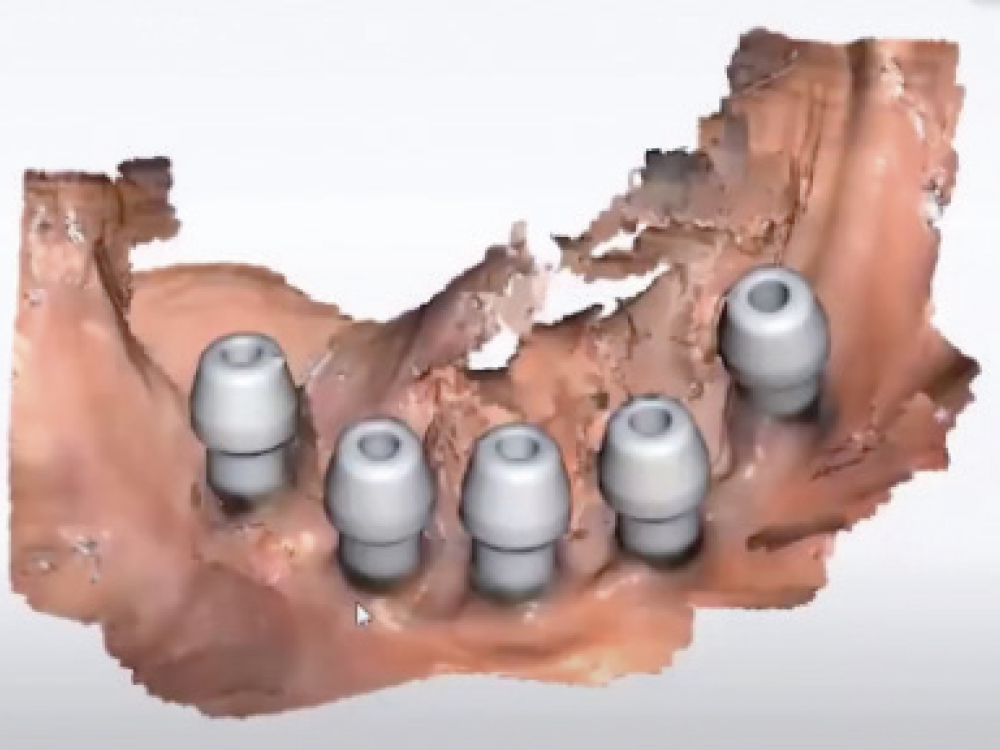

Intraoral scanners create three-dimensional virtual models of the oral environment by capturing and stitching together multiple optical images. When recording implant positions, clinicians use scan bodies — components that attach to the implant or multi-unit abutment. The scanner captures each scan body’s geometry, and software converts the images into a stereolithography (STL) file. This digital file is imported into specialized design software for prosthetic planning and fabrication.

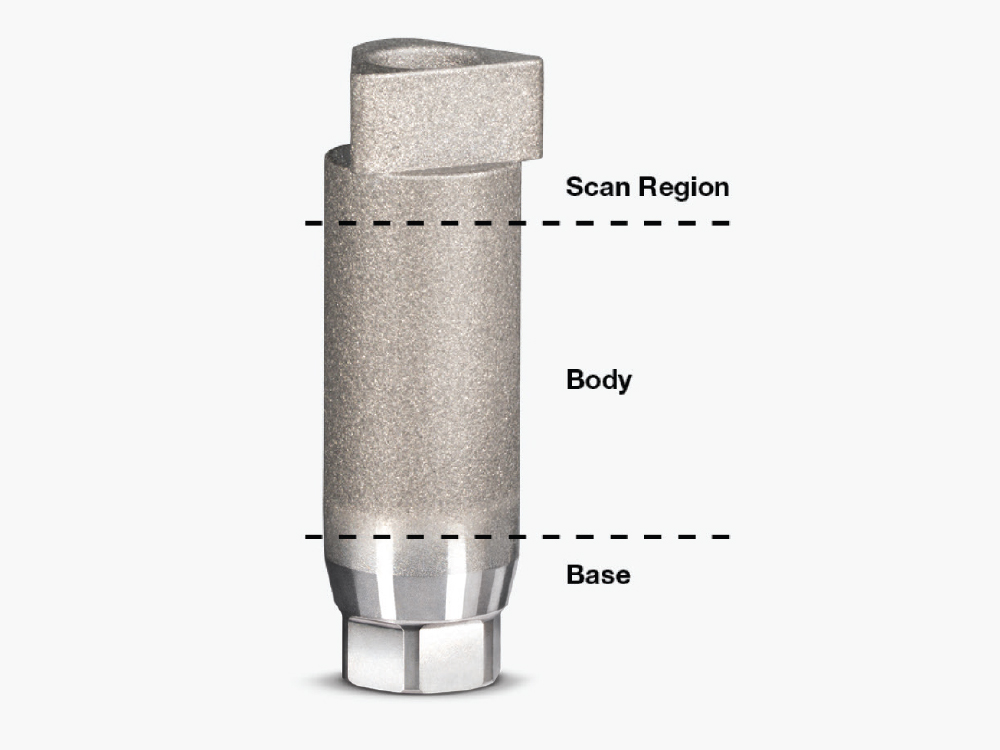

Traditional vertical scan bodies are divided into three parts: the base, body and scan regions. The base of a scan body ensures precise mechanical engagement and positional accuracy with the implant connection, while the body provides the necessary height, visibility, and geometric reference for accurate optical scanning and software alignment. The top third — called the “scan region” is the most critical for accurately recording implant positioning (Fig. 1). Studies have found that, for single and multiple implants, intraoral scanning is as accurate or even more accurate than traditional analog impressions.1,2 However, full-arch digital impressions remain significantly more complex due to the larger area and lack of stable reference landmarks.

CHALLENGES AND FACTORS INFLUENCING ACCURACY

Several clinical, environmental and technical factors influence the accuracy of intraoral scanning in full-arch implant cases:

- Clinical and Intraoral Conditions: Blood, saliva, and soft-tissue mobility can distort light reflection and image acquisition. During scanning, movement or deformation of the tongue and mucosa may alter the geometry of captured surfaces, leading to inaccuracies in the final digital impression.3

- Patient Factors: Full-arch scanning requires longer acquisition times. Limited mouth opening, implant angulation, and patient movement increase the likelihood of minor errors. Even small movements during scanning can produce stitching inconsistencies across the arch.

- Large Scan Area: Capturing an entire arch requires the scanner to record and stitch together many small overlapping images.4 This process becomes more difficult in edentulous cases due to the absence of natural reference points such as teeth. As the scan progresses, small errors compound, resulting in measurable deviations over longer spans.

- Multiple and Varying Implant Angulations: Implants placed at varying angulations pose additional scanning difficulties. The scanner must precisely register each implant’s position and orientation. Greater angulation differences and more implants typically lead to increased positional deviation.5

- Scan Body Design: The design, material, and surface texture of scan bodies directly affect scan accuracy. Reflective materials or inconsistent geometries may cause data distortion. The visibility and accessibility of the scan body also determine how effectively the scanner can capture its critical surfaces.6

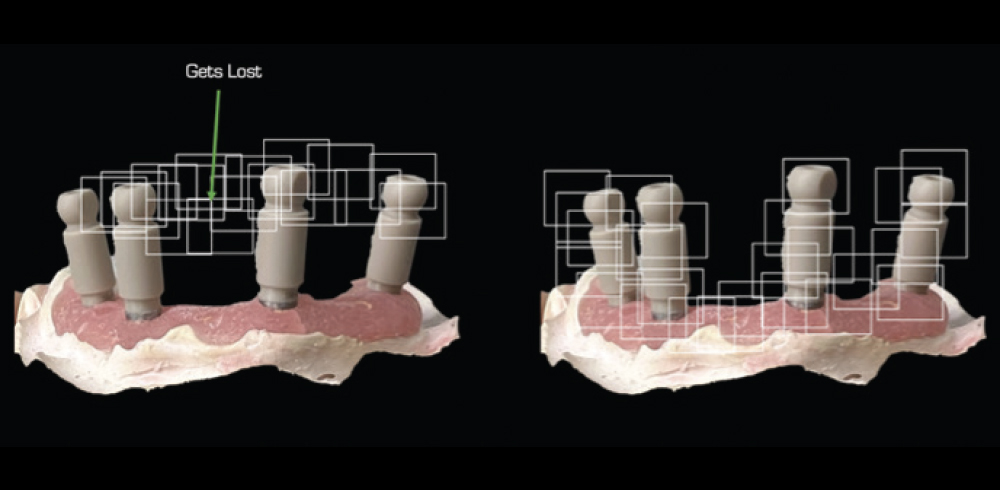

- Z-Effect: The “Z-dimension” is the distance from the implant platform to the scan region. Intraoral scanners must have overlapping images to be able to stitch accurately. With full-arch implant scanning, clinicians must capture several scan regions accurately. However, if the intraoral scanner goes between neighboring scan regions, it will get “lost in space.” Thus, the intraoral scanner must trace the length of the scan body and the neighboring soft tissue before obtaining information from the neighboring scan body. This “Z-effect” leads to inaccuracies with conventional, vertical scan bodies.7 (Fig. 2)

- Operator Experience: Scanning technique plays a critical role in success. Novice operators may struggle to maintain consistent motion and overlap between frames. Even experienced clinicians can encounter difficulties when capturing a full arch due to complex geometry and extended scanning time.

- Scanning Strategy: The scanning path — whether segmental or continuous — affects accuracy. Segmental scans, where smaller areas are captured and merged, may reduce accumulated error.8Continuous scans, though faster, increase the risk of tracking loss or stitching distortion.

- Scanner Limitations: Each intraoral scanning system has unique hardware and software capabilities. Some scanners are optimized for short spans or natural dentition but may not perform well for large, edentulous areas. Factors such as image acquisition rate, processing algorithms and calibration quality influence final results.9

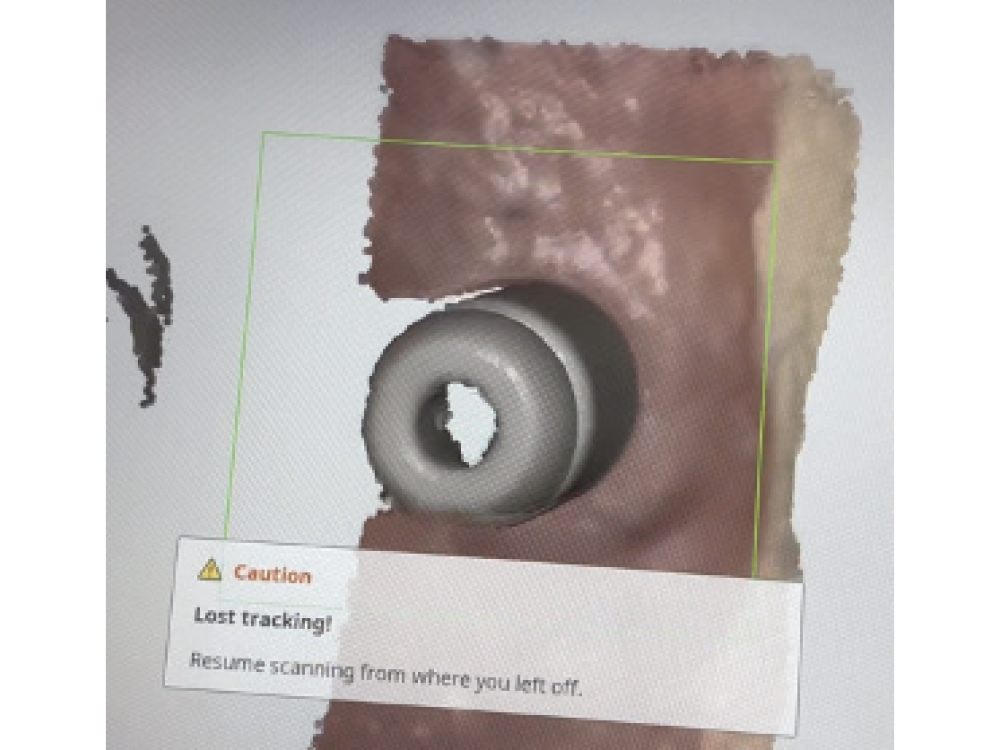

- Stitching Errors: The most significant limitation in full-arch scans is stitching errors. Because intraoral scanners record only a small portion of the arch at once, they rely on overlapping landmarks to merge data accurately. In edentulous cases, the lack of stable landmarks — combined with mobile mucosa — can cause the scanner to “lose orientation” and create distorted digital models (Fig. 3). Studies consistently show that the greater the distance between implants, the higher the cumulative stitching error.10

SIMPLIFYING FULL-ARCH IMPLANT SCANNING

To improve intraoral scan accuracy for full-arch implants, clinicians and manufacturers have developed innovative techniques and scan bodies to help navigate the large scan areas and stitching inaccuracies involved with traditional, vertical independent scan bodies.

One scan system that has simplified full-arch implant scanning and streamlined the process of All-on-X prosthetic fabrication is the OptiSplint® system from Digital Arches (Fountain Valley, Calif.). The OptiSplint system is a dual-purpose implant coping system designed specifically for fixed, complete-arch prostheses.

It allows clinicians to record implant positions with improved accuracy by maintaining continuity between scan bodies throughout the scan. Instead of capturing each scan body independently, it uses a connected scan base system that links all implants together. This ensures the scanner reads the entire structure as a unified object, reducing the cumulative stitching errors and allowing the scanner to maintain orientation across the entire arch.

The OptiSplint system not only records full-arch implant positioning but carries a unique workflow that allows for immediate or final All-on-X prosthetic fabrication through a fully digital workflow. Glidewell is among the select certified partner laboratories in the United States authorized to process cases using the OptiSplint system.

Components Of The Optisplint System

OptiSplint Scan Bodies

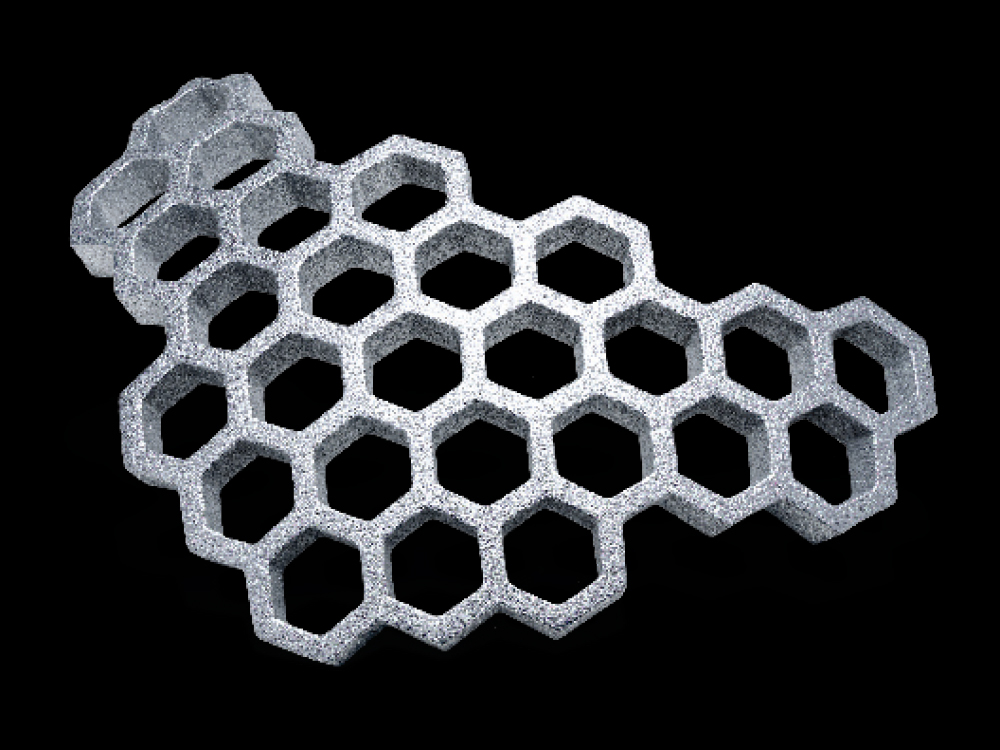

OptiSplint Frame

Frame Carrier

Reverse Analog Scan Caps

Scannable Healing Caps

The Optisplint Technique

Step 1: Placement of Individual Scan Bodies

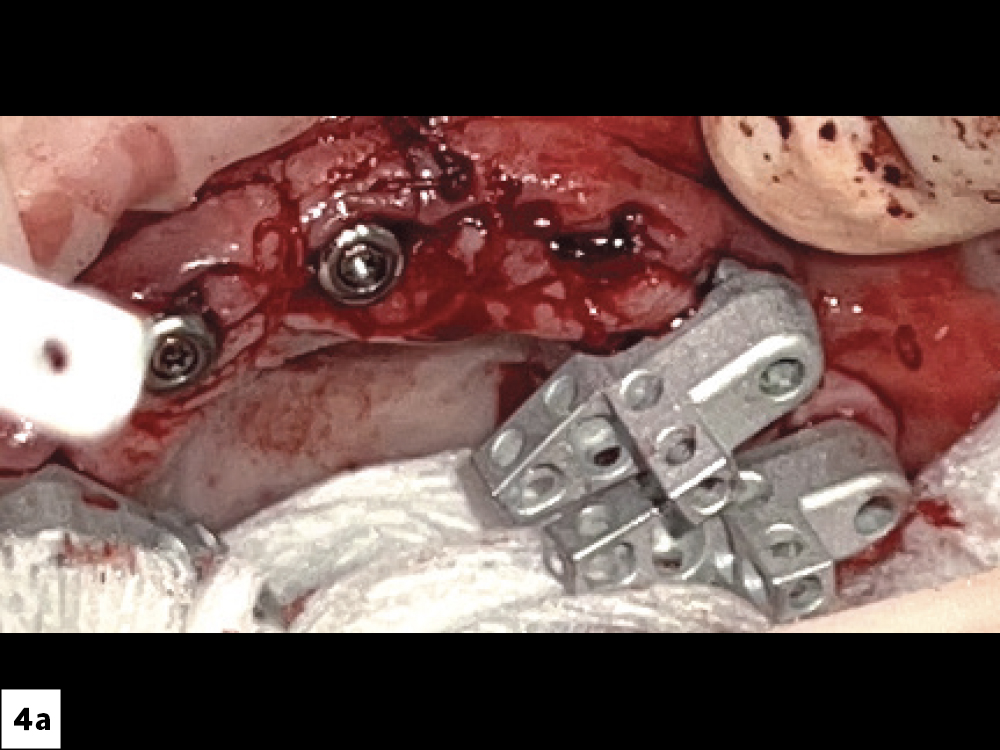

The individual scan body is placed on each respective multi-unit abutment (Fig. 4a). Unlike traditional vertical scan bodies, the OptiSplint design incorporates a wing-like projection extending laterally from the scan region. The placement of the scan bodies should be oriented in a way where all the wing-like projections are extended toward one another (Fig. 4b). This is primarily toward the palate (maxilla) or lingual (mandible) but can be extended facially or buccally if orientation allows. The positioning should be done where the scan bodies are positioned as close as possible without being in contact.

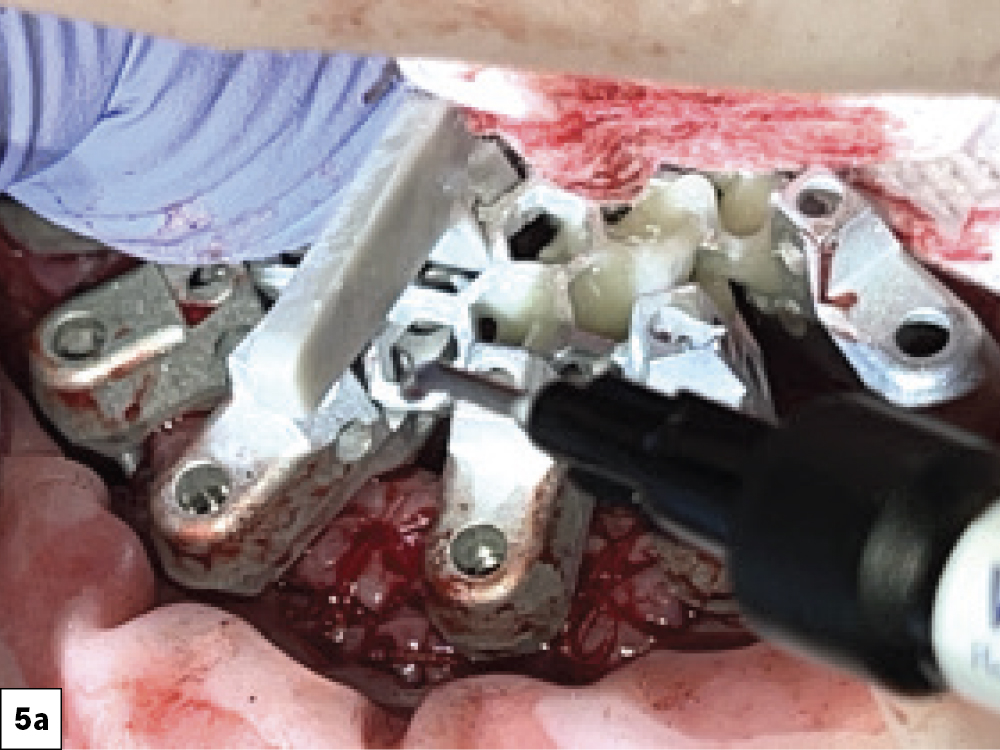

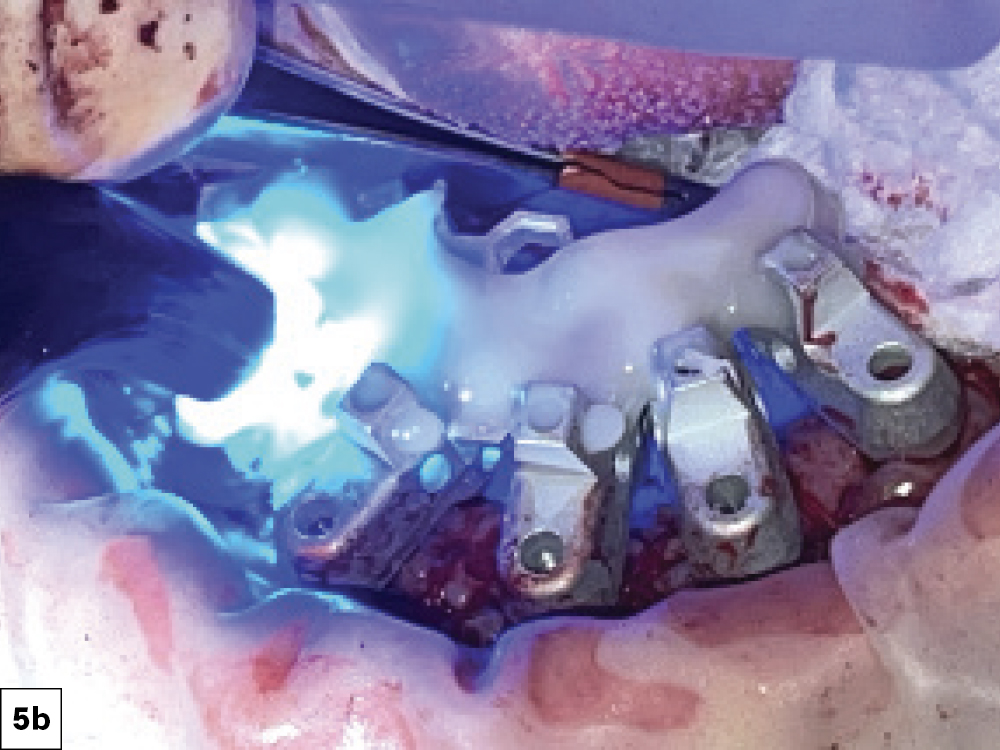

Step 2: Connecting the Honeycomb Frame

After all scan bodies are placed and hand tightened, the OptiSplint frame is luted to the scan bodies. A lightweight honeycomb metal frame is placed intraorally within 1–2 mm of the scan body wings (Fig. 5a). The frame is then luted to the scan bodies using resin or acrylic material. Once cured, all scan bodies are splinted into one rigid assembly (Fig. 5b).

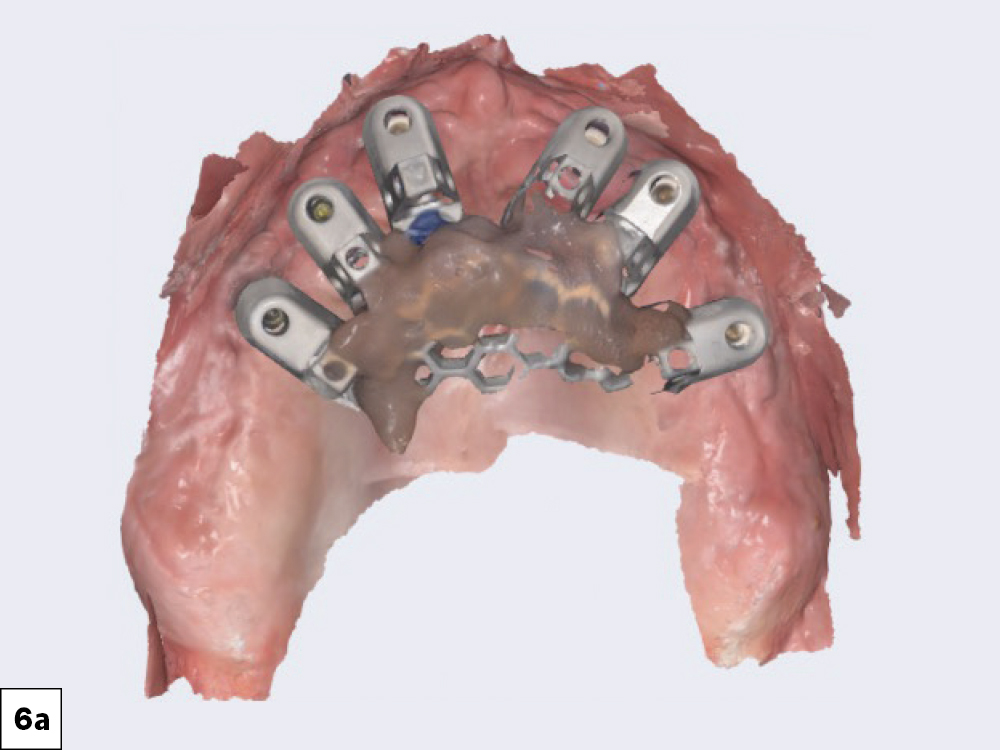

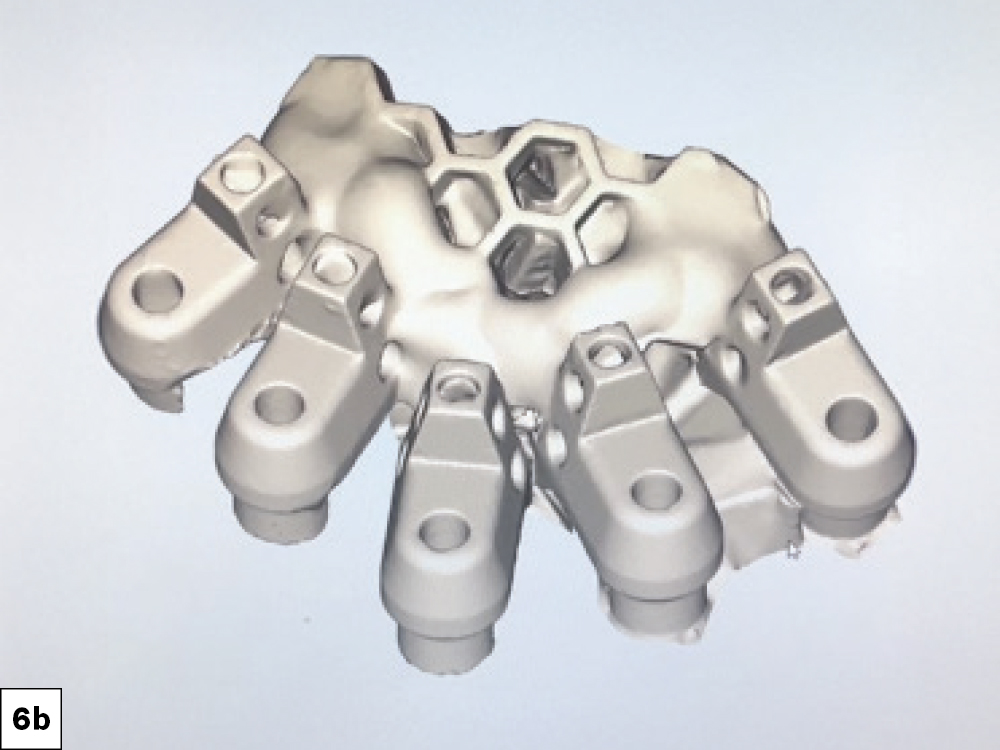

Step 3: Scanning the Splinted Structure

One of the most unique aspects of the OptiSplint system is how it can be scanned intraorally (Fig. 6a) or extraorally (Fig. 6b). Extraoral scanning eliminates many patient-related errors such as movement, saliva interference and limited access.

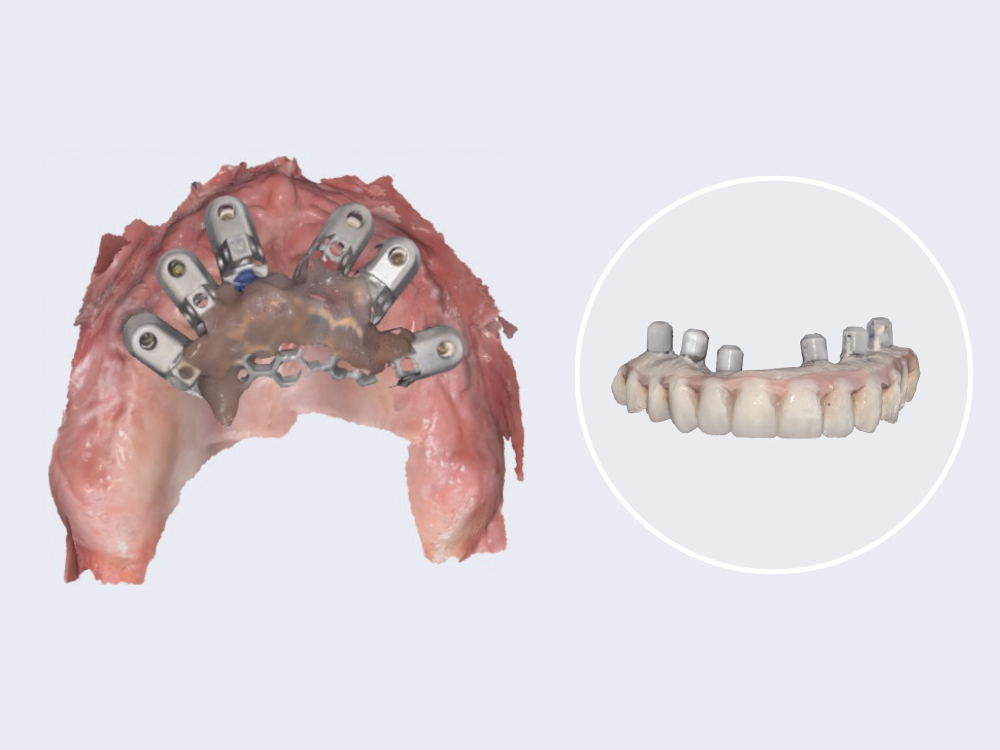

Step 4: Fabricating the Verification Jig

The OptiSplint system can also serve as a verification jig. Once the OptiSplint structure is connected together, it is removed from the mouth. Multi-unit analogs can be placed into the structure and poured in dental stone, creating a master model. This allows clinicians to verify prosthetic passivity prior to delivery (Figs. 7a, 7b).

Step 5: Capturing Soft-Tissue Information

The splinted OptiSplint structure registers implant positioning. In order to capture the soft-tissue information in between multi-unit abutments, a soft-tissue record must be taken. The scannable healing caps can then be inserted into the multi-unit abutments (Fig. 8). These can either be scanned, or an impression of the healing abutments can be taken and scanned extraorally.

Step 6: Recording Tooth Positioning

This digital workflow captures records to fabricate an All-on-X prosthesis. At this stage in the workflow, a clinician will have the implant position from the OptiSplint structure and the soft-tissue information from the scannable healing caps. In the digital era, there are several methods of recording where the teeth need to be:

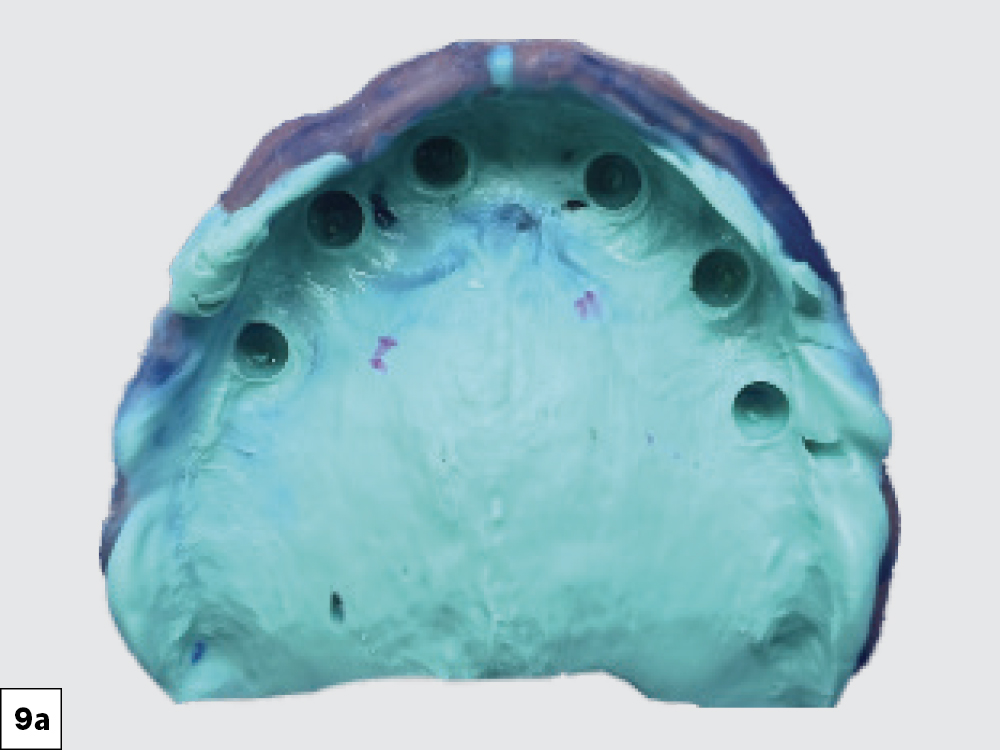

a) Use of a Denture – If the patient has a denture (conventional or immediate), a reline impression can be taken within the denture, capturing the scanning healing caps (Figs. 9a, 9b). This can then be scanned 360 degrees extraorally with an intraoral scanner or desktop scanner.

b) Converted Prosthesis – If the patient has a converted prosthesis, reverse scan analogs can be placed in the intaglio of the prosthesis. This prosthesis can then be scanned 360 degrees extraorally. This is done most commonly when transitioning the patient from the interim or temporary prosthesis to the final fixed prosthesis. (Fig. 9c).

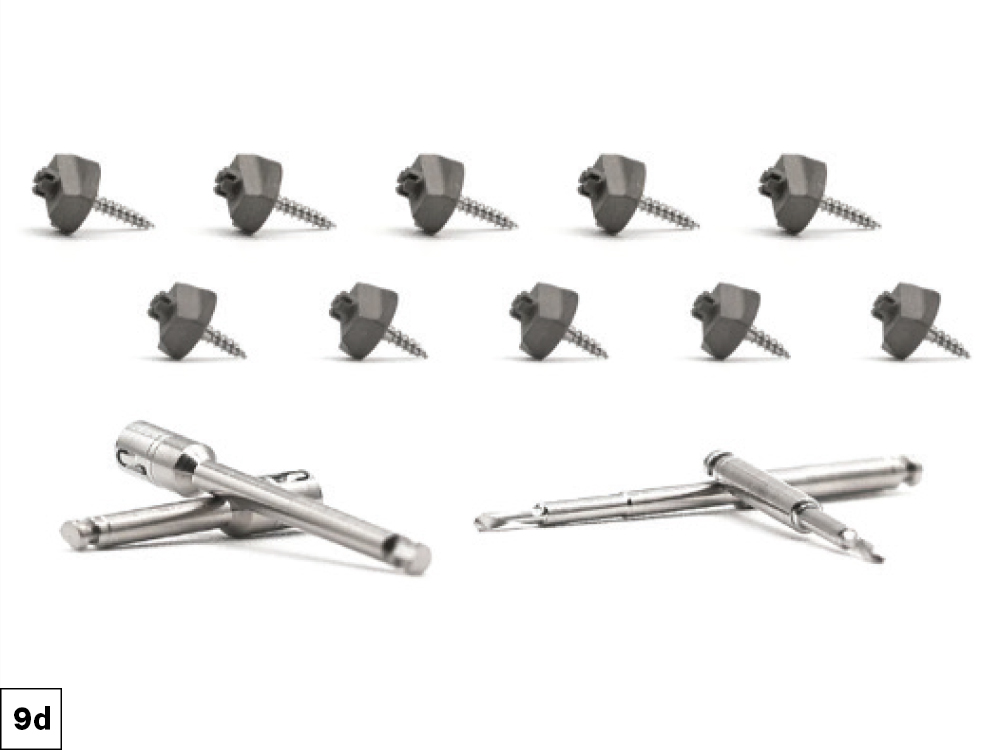

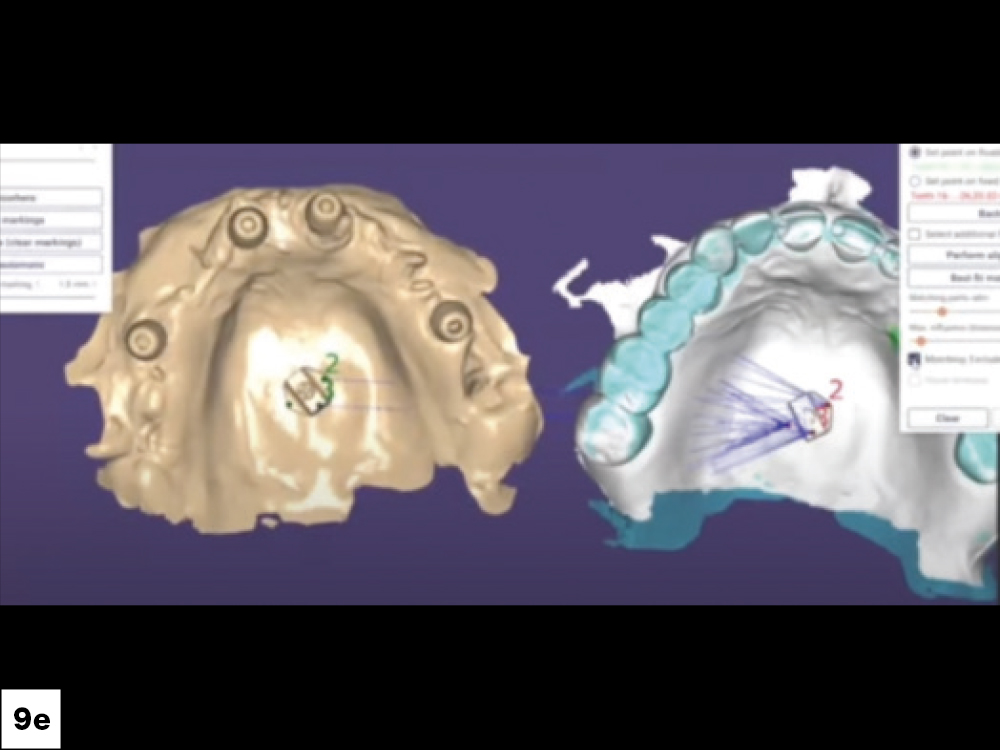

c) Fiducial Markers – If the OptiSplint system is going to be utilized for an immediate load All-on-X procedure, fiducial markers can be utilized to help record tooth positioning. Fiducial markers are screws that can be fixated prior to extracting the teeth and implant placement. A preoperative scan can be taken of the patient’s preoperative dentition with the fiducial marker. The fiducial marker should remain in place for the entirety of the procedure. After the implants are placed and positioning is recorded, a postoperative scan of the fiducial marker with the scannable healing caps is made. ArchTracer™ fiducial markers (Digital Arches) can be easily utilized to merge data sets. (Figs. 9d, 9e).

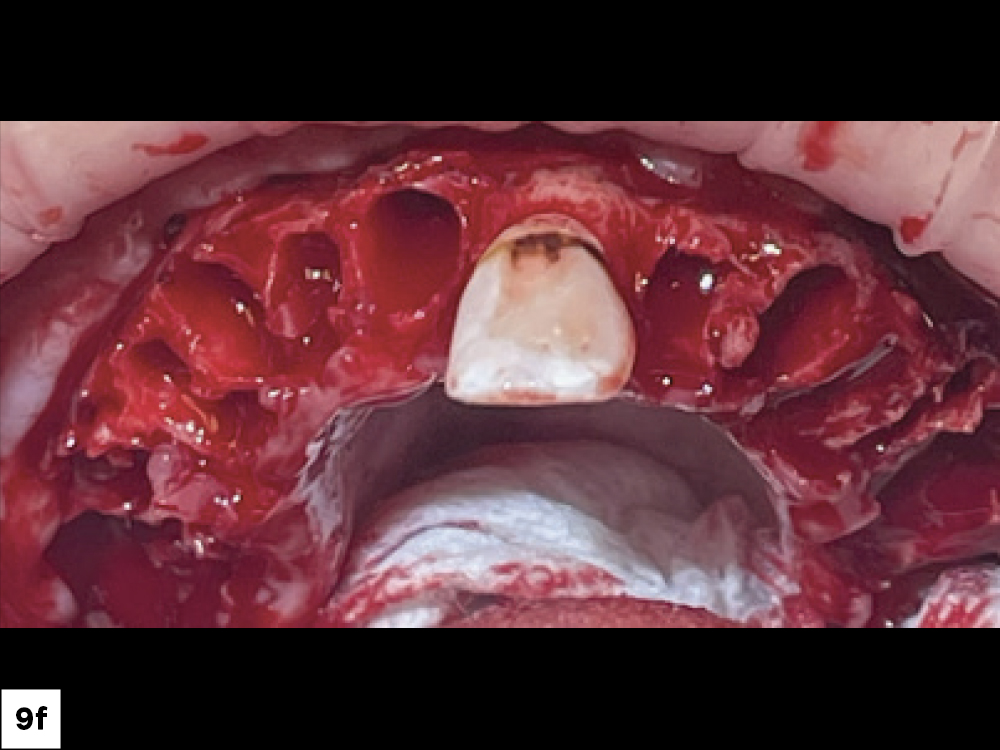

d) Leave Select Abutment Teeth – If the OptiSplint system is going to be utilized for an immediate load All-on-X procedure, select abutment teeth can be utilized to help record tooth positioning. If there are non-mobile teeth that are not going to impact implant placement, these teeth can be left to serve as an alignment tool, from pre-implant placement and post-implant placement. (Fig. 9f).

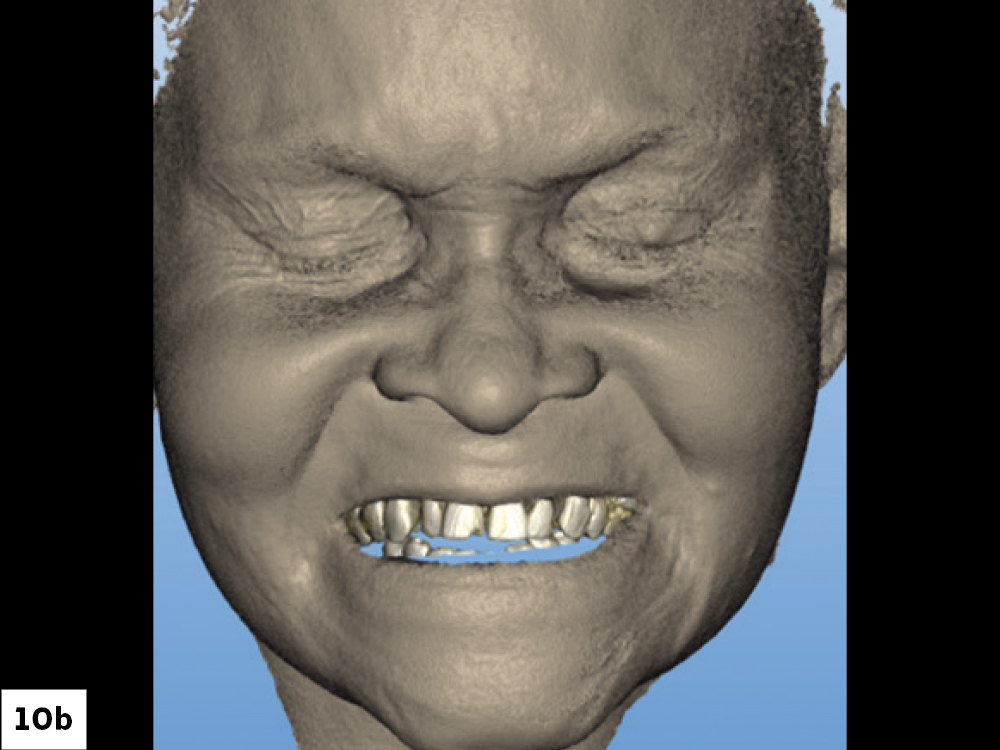

Step 7: Facial Record

Digital design has improved the All-on-X workflow. Incorporation of a facial record (2D photos or 3D facial scanning) leads to greater accuracy and lab communication. (Figs. 10a, 10b).

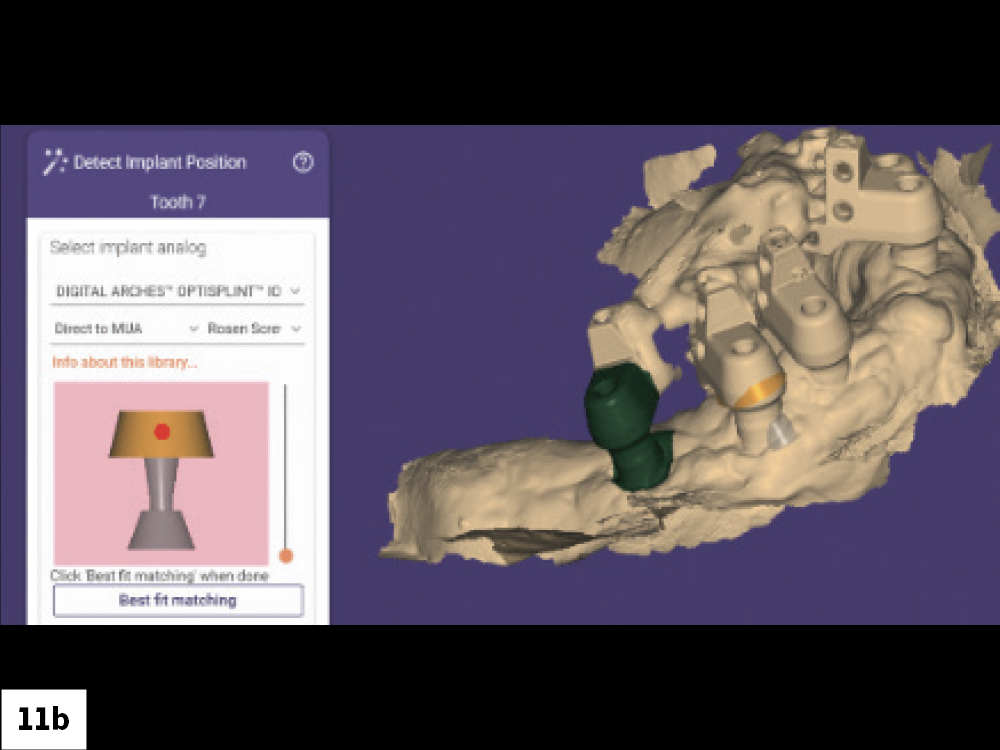

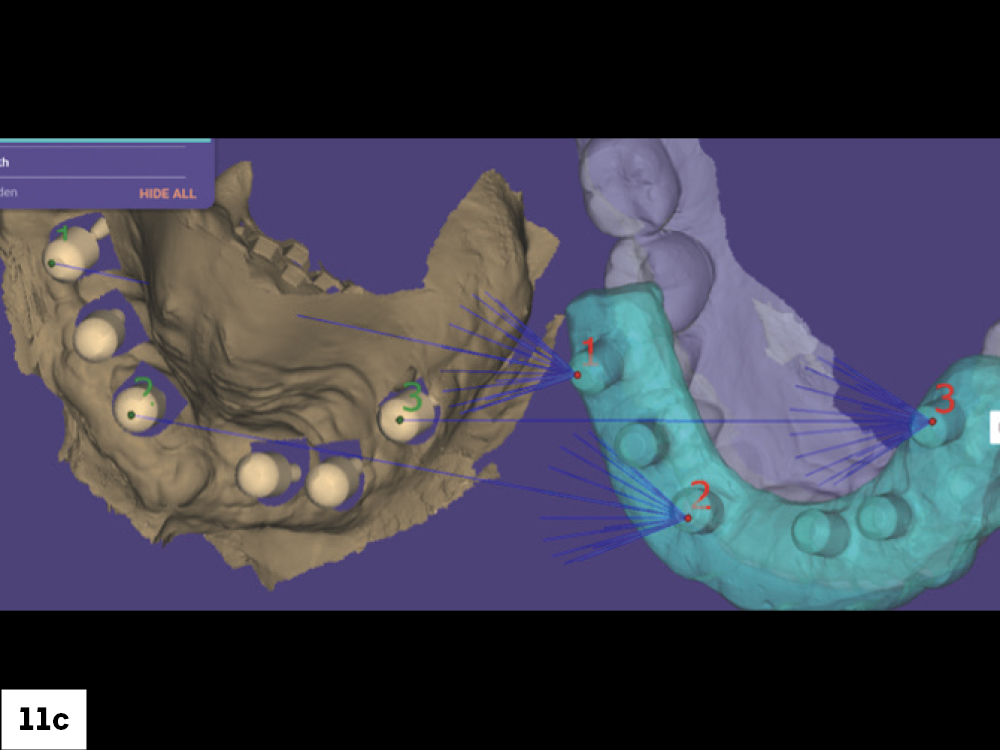

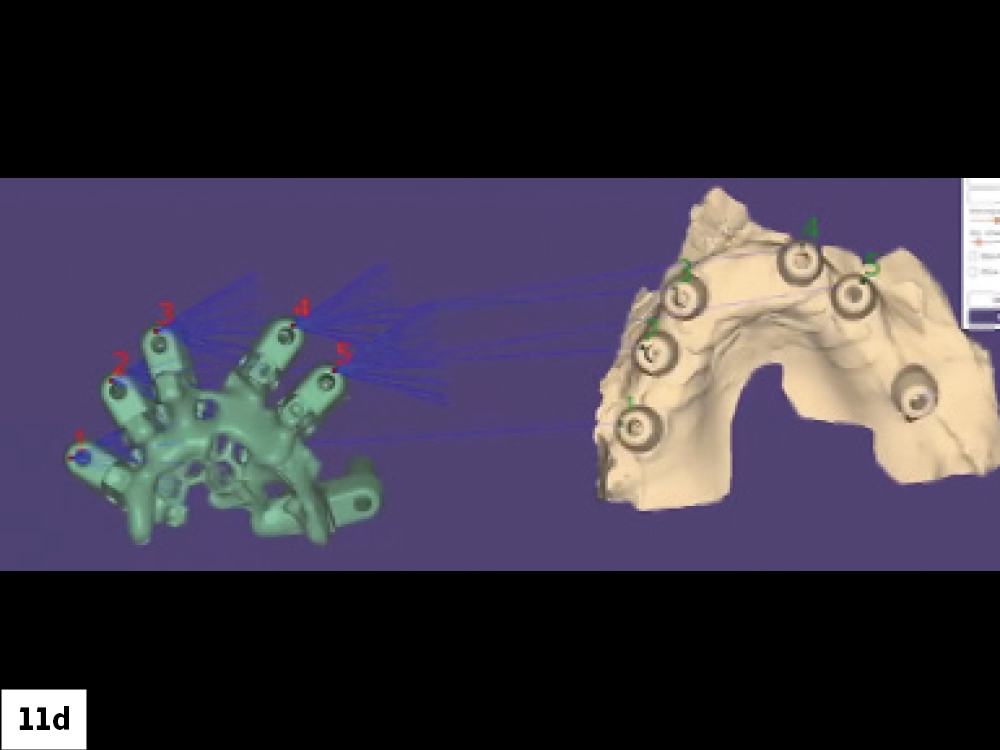

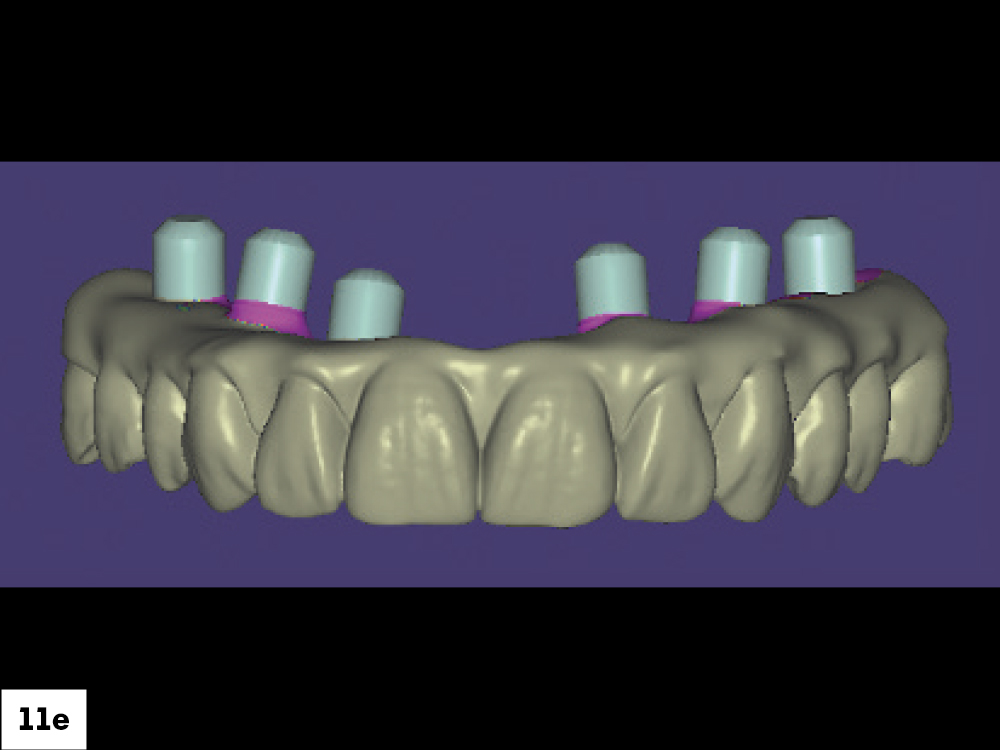

Step 8: Merging of Data

After all the data is recorded, the information should then be sent to the lab. There, the information is imported into CAD software. Files are then aligned to digitally design the All-on-X prosthesis. The lab merges all the files, designs the prosthesis, and fabricates the immediate or final fixed prosthesis.

Advantages of the OptiSplint Workflow

- Enables a fully digital All-on-X workflow using standard intraoral scanning systems

- Eliminates intraoral challenges by allowing extraoral scanning

- Functions as both a scan body and a verification jig

- Provides cost-effective accuracy compared to photogrammetry

- Simplifies data alignment for CAD design and fabrication

Conclusion

Intraoral scanners have revolutionized restorative dentistry, offering unparalleled convenience and integration within digital workflows. Yet, when extended to full-arch implant impressions, their limitations become evident. The challenges of scanning large edentulous spans, managing implant angulation, and avoiding stitching errors make achieving precise implant position registration difficult.

Systems like OptiSplint enable clinicians to achieve high-accuracy digital impressions using standard intraoral scanning technology. The use of connected scan base systems allows continuous data acquisition, reducing stitching errors and improving accuracy.

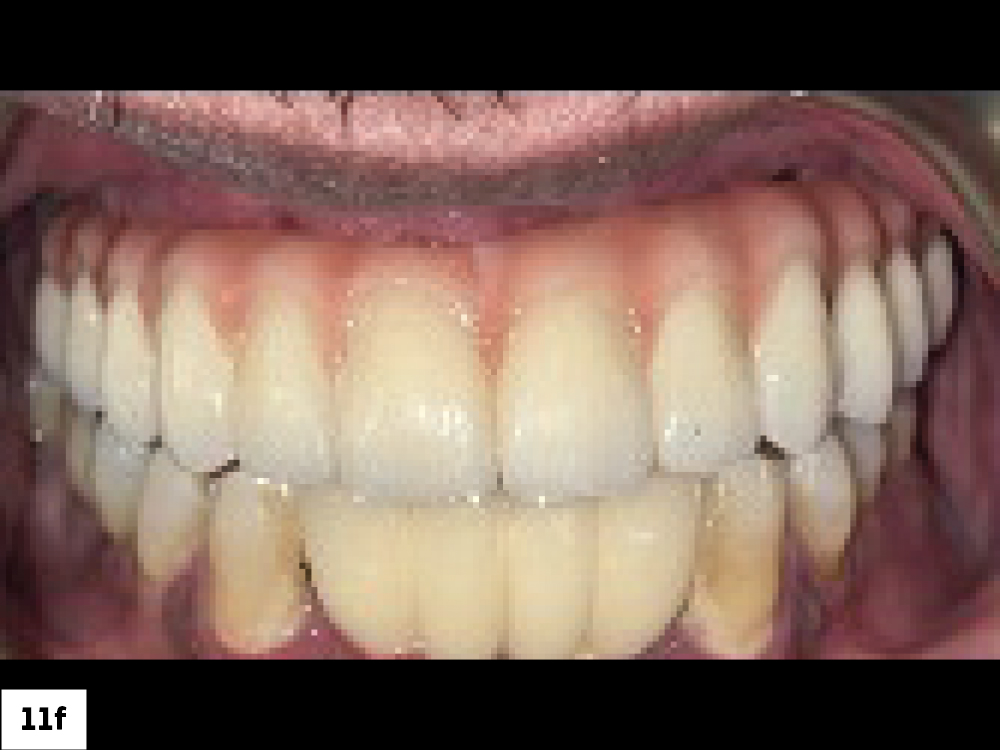

The integration of these technologies signifies a new era in implant dentistry — one where digital precision, clinical efficiency and patient satisfaction converge. As tools and techniques continue to evolve, clinicians equipped with digital knowledge and adaptable workflows will be best positioned to deliver predictable, high-quality implant restorations.

Available CE Course

References

-

Albanchez-González MI, Brinkmann JC, Peláez-Rico J, López-Suárez C, Rodríguez-Alonso V, Suárez-García MJ. Accuracy of digital dental implants impression taking with intraoral scanners compared with conventional impression techniques: A systematic review of in vitro studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Feb 11;19(4):2026.

-

Schmidt A, Wöstmann B, Schlenz MA. Accuracy of digital implant impressions in clinical studies: A systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2022 Jun;33(6):573–85.

-

Mangano FG, Admakin O, Bonacina M, Lerner H, Rutkunas V, Mangano C. Trueness of 12 intraoral scanners in the full-arch implant impression: a comparative in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20.

-

Gehrke P, Rashidpour M, Sader R, Weigl P. A systematic review of factors impacting intraoral scanning accuracy in implant dentistry with emphasis on scan bodies. Int J Implant Dent. 2024 May 1;10(1):20.

-

Gherlone EF, Ferrini F, Crespi R, Gastaldi G, Capparé P. Digital impressions for fabrication of definitive ‘all-on-four’ restorations. Implant Dent. 2015 Feb;24(1):125–9.

-

Mizumoto RM, Yilmaz B. Intraoral scan bodies in implant dentistry: A systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2018 Sep;120(3):343–52.

-

Mizumoto RM, Yilmaz B, McGlumphy EA Jr, Seidt J, Johnston WM. Accuracy of different digital scanning techniques and scan bodies for complete-arch implant-supported prostheses. J Prosthet Dent. 2020 Jan;123(1):96–104.

-

Hardan L, Bourgi R, Lukomska-Szymanska M, Hernández-Cabanillas JC, Zamarripa-Calderón JE, Jorquera G, Ghishan S, Cuevas-Suárez CE. Effect of scanning strategies on the accuracy of digital intraoral scanners: a meta-analysis of in vitro studies. J Adv Prosthodont. 2023 Dec;15(6):315–32.

-

Meneghetti PC, Li J, Borella PS, Mendonça G, Burnett LH Jr. Influence of scan body design and intraoral scanner on the trueness of complete arch implant digital impressions: An in vitro study. PLoS One. 2023 Dec 19;18(12).

-

Di Fiore A, Meneghello R, Graiff L, Savio G, Vigolo P, Monaco C, Stellini E. Full arch digital scanning systems performances for implant-supported fixed dental prostheses: A comparative study of 8 intraoral scanners. J Prosthodont Res. 2019 Oct;63(4):396–403.