Prophylactic Antibiotic Use in Implant Dentistry (1 CEU)

Because of the increased use of dental implants in dentistry today, a thorough understanding of the indications and specific usage of prophylactic antibiotics is essential. The morbidity associated with implant-related complications can be significant, making prophylactic antibiotic use commonly indicated pre- and postoperatively. Unfortunately, there is currently no generalized consensus on an ideal prophylactic antimicrobial regimen. In this article, I present an antibiotic protocol based on patients’ health statuses and the invasiveness of dental implant procedures.

WHY ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS MATTERS

A devastating potential complication after implant surgery is infection. Postoperative infectious episodes may lead to a multitude of problems, including pain, swelling, loss of bone and possible failure of the implant. Postoperative wound infections can have a significant effect on the success of dental implants and bone grafting procedures. The occurrence of surgical host defenses allows for an environment conducive to bacterial growth. This process is complex due to interactions with the host, local tissues, and systemic and microbial virulence factors.

Over 65% of implants that become infected require removal.1 After an implant failure and removal, studies have shown that the success rate of the implant replacement drops to 71% and drops further to only 60% for implant sites that have exhibited two failures.2,3 To prevent these possible devastating complications, prophylactic measures can be utilized to minimize infections. The most ideal prophylactic treatment includes the use of antimicrobial medication, which has been shown to significantly reduce postoperative infections and decrease failure rates in implant cases.4,5,6

The main goal of prophylactic antibiotic use is to prevent infection during the initial healing period from the surgical wound site, thus decreasing the risk of infectious complications of the soft and hard tissues. Numerous studies showcase decreased infectious episodes when preoperative antibiotics are used in dental implantology.7,8,9,10

PRINCIPLES OF ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS

A prophylactic pharmacologic protocol has been developed that encompasses the patient’s medical status, as well as the invasiveness and risk of surgical infection. This protocol is based on principles that have been established in implant literature. Dr. L.J. Peterson, a pioneer in antibiotic prophylaxis research, postulated various principles that have been well accepted in medicine today:11

Principle 1: The procedure should have a significant risk for and incidence of postoperative infection

Elective dental implant surgery falls within the Class 2 (clean/contaminated) category by the American College of Surgeons. Class 2 medical and dental surgical procedures have been shown to have an infection rate of approximately 10% to 15%. However, with proper surgical techniques and the use of prophylactic antibiotics, the incidence of infection may be reduced to less than 1%.12,13 With Class 2 surgeries, prophylactic antibiotics are recommended.

Principle 2: The appropriate antibiotic for the surgical procedure must be selected

The prophylactic antibiotic should be effective against the bacteria that are most likely to cause an infection. In the majority of cases, infections after surgery are from organisms that originate from the surgery site.11 Therefore, the medications included in the protocol consist of antibiotics that are specific for the bacteria that is most likely to cause an infection with that particular procedure.

Principle 3: An appropriate tissue concentration of the antibiotic must be present at the time of surgery

For an antibiotic to be effective, a sufficient tissue concentration must be present at the time of bacterial invasion. To accomplish this goal, the antibiotic should be prescribed in a dose that will reach plasma levels that are three to four times the minimum inhibitory concentration of the expected bacteria.14 If antibiotic administration occurs after bacterial contamination, infection reduction is compromised.

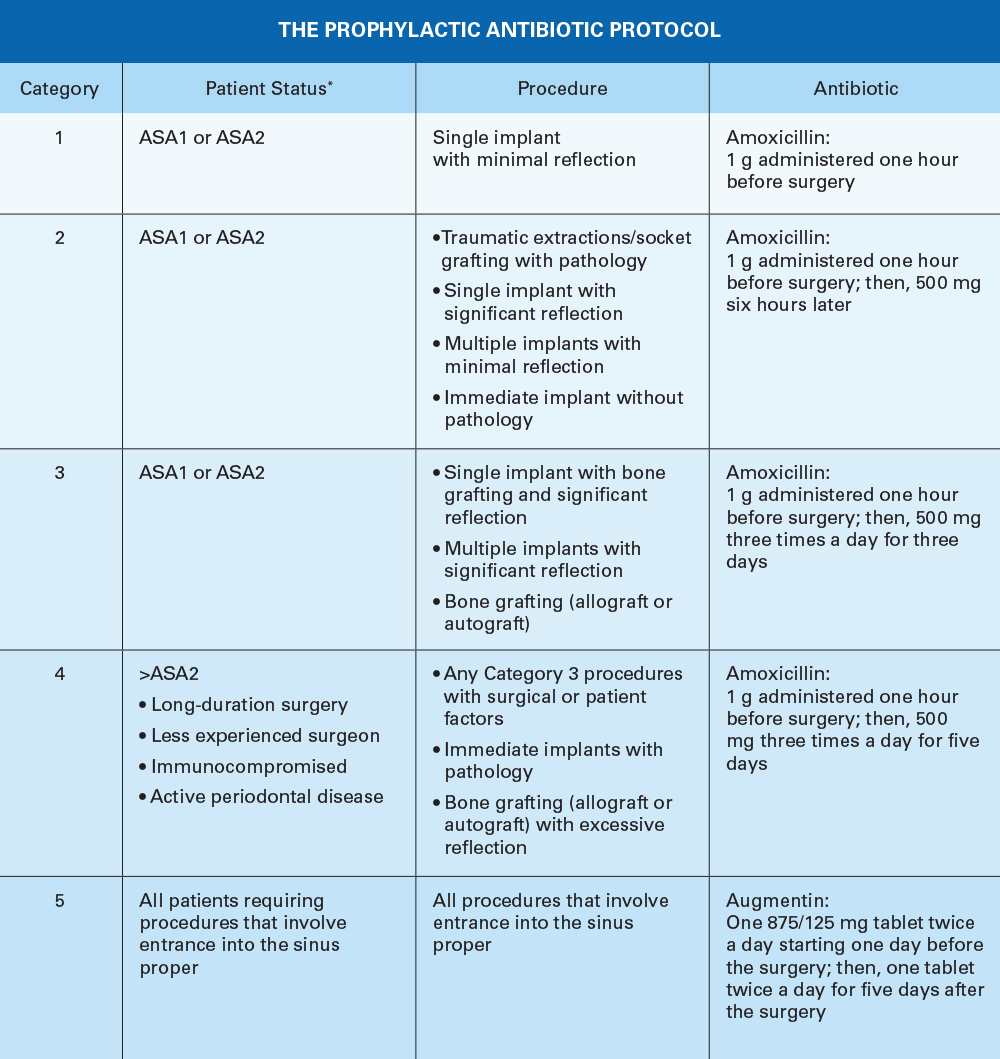

THE ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS PROTOCOL

The following list of antibiotics, along with alternative medications, is suggested for the pathogens known to cause postoperative surgical wound infections in implant and bone grafting surgery.

Antibiotics for Implant Placement and Bone Grafts:

- Amoxicillin (500 mg)

- Cephalexin (nonanaphylactic allergy to penicillin) (500 mg)

- Doxycycline (anaphylactic allergy to penicillin) (100 mg)

Antibiotics for Sinus Augmentation or Sinus Grafts:

- Augmentin® (875/125 mg)

- Cefuroxime axetil (Ceftin®) (500 mg)

- Doxycycline (100 mg)

Local Antibiotic:

Cefazolin (Ancef) (1 g)

CONTROVERSIAL PROPHYLACTIC ANTIBIOTIC TOPICS

In the development of this pharmacologic protocol, numerous factors play a significant role in determining the appropriate antibiotic, an alternative antibiotic and administration timing. The following discussion addresses these topics.

Penicillin Allergy Incidence

There exists much controversy concerning reported information on patients who present with a penicillin allergy. Unfortunately, penicillin antibiotics have been associated with false information and poor studies over the years:

- Approximately 10% of patients report a history of allergy to a penicillin-derivative antibiotic. 90% of those patients are not truly allergic to penicillin.

- Less than 1% of the population is truly allergic to penicillin.

- About 80% of patients with IgE-mediated reactions lose their sensitivity after 10 years.

Because of the high rate of self-reporting penicillin allergies, many patients are treated with alternative antibiotics (like clindamycin phosphate), which predispose patients to an increased number of complications.

High Implant Failure Rates for Penicillin-allergic Patients

Studies report a high failure rate for patients who cannot take a ß-lactam (beta-lactam) antibiotic like penicillin. These studies conclude that, if the patient is treated with a non-ß-lactam antibiotic, they are at a higher risk of implant complications and failure. Patients not treated with ß-lactam antibiotics experienced higher implant failure rates.

Implant Failure Studies with Penicillin-allergic Patients

Why Are Some Patients in a Higher-risk Category?

Currently, clindamycin is the most commonly used alternate antibiotic for penicillin-allergic patients. Unfortunately, unbeknownst to most clinicians, there are disadvantages that come with clindamycin use, such an increase in infections, implant failure, bone regeneration and peri-implantitis.

Clindamycin Studies

- 2006 Wagenberg study: 5.7 Times the failure rate15

- 2007 Duewelhenke study: Cytoxic effects on osteoblasts17

- 2008 Naal study: Reduced alkaline phosphatase18

- 2015 Rashid study: Increased peri-implantitis bacteria, prevotella19

- 2018 Khoury study: Increased sinus graft infections20

- 2018 Salomó-Coll study: 25% Implant failure rate21

- 2021 Basma study: 10.7% Failure rate for socket grafts and 22.5% failure rate for ridge augmentations22

- 2022 Bagheri study: 19.9% Failure rate16

These studies conclude that clindamycin is not only ineffective for implant surgery but also harmful.

Therefore, the use of prophylactic clindamycin for implant patients has actually been shown to increase complications and have a higher associated implant failure rate.

Alternatives for Penicillin-allergic Patients

The most ideal antibiotic for prophylaxis prior to implant surgery is a ß-lactam antibiotic. In dentistry, the two most common types of ß-lactam antibiotics are those in the penicillin and cephalosporin families.

Unfortunately, false information concerning the cross-reactivity between penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics once led to an inaccurate belief: Some believed the similarity that resulted in allergies was derived from the similarity of the ß-lactam ring. However, that has been disproven. Even though both antibiotic classes have ß-lactam rings, the cross-reactivity has been linked to one of the two side chains, termed “R1.” The first generation cephalosporins have a similar R1 side chain to the penicillin family, but the second, third, fourth and fifth generations have dissimilar R1 side chains.

Therefore, if a patient presents with a known Type 1 hypersensitivity to penicillin, first generation cephalosporins, like Keflex®, should not be prescribed because their R1 side chains are similar. However, the second, third, fourth and fifth generations have dissimilar R1 side chains. The use of these drugs is encouraged, as the cross-reactivity is very low and is medicolegally defensible by the currently available evidence.23

Antibiotic Use for Sinus Augmentations

Because of the high rate of bacterial resistance, amoxicillin is no longer used for antibiotic prophylaxis for sinus graft surgery. Instead, amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) is recommended because of the addition of clavulanic acid. The clavulanic acid enhances the amoxicillin’s activity against the ß-lactamase — producing strains of bacteria that are prevalent in the maxillary sinus. Clavulanate acid, which is also an antibiotic, has a high affinity for the ß-lactamase. Because of this interaction, the ß-lactamase is inactivated.

As an alternative antibiotic, patients may take cefuroxime axetil (Ceftin), which is a second-generation cephalosporin.24 Numerous studies have substantiated its use in patients who report having a penicillin allergy.14,25,26 Ceftin possesses good potency, efficiency and strong activity against resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae bacteria. A second alternative antibiotic is doxycycline (100 mg). Doxcycline has recently been recommended by the ADA but has less efficacy within the sinus than ß-lactam antibiotics.

Prescribing Sinus Antibiotics 24 Hours Before Surgery

The maximum effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotic drugs occurs when the antibiotic is in adequate concentrations in the tissue prior to bacterial invasion. Because the sinus mucosa has limited blood supply to combat possible bacterial invasion from the sinus surgery, along with a high incidence of tissue inflammation, antibiotic medications should be administered at least one full day prior to surgery and extended for five days after surgery.

Prescribing Local Antibiotic Medications

The antibiotic concentration within a blood clot of a bone or sinus graft depends on the systemic blood titer. After the clot stabilizes, further antibiotic drugs do not enter the area until revascularization.27 The bone graft becomes a “dead space,” with minimal blood supply and the absence of protection by the host’s cellular defense mechanisms. This leaves the graft prone to infections that would normally be eliminated by either the host defenses or the antibiotic. The osteogenic induction of autografts and allografts is greatly impaired when contaminated with infectious bacteria.28 Allograft-related infection rates, like those related to bacterial colonization, have shown an incidence of approximately 4–12%.29

To ensure adequate antibiotic levels in a graft, it is commonly recommended to add a local antibiotic to the graft mixture.30 The local antibiotic can protect the graft from early contamination and infection, without any deleterious effects on bone growth. Antibiotic drugs such as penicillin and cephalosporins have been found to be non-destructive to bone-inductive proteins.31 The locally delivered antibiotic should have efficacy against the most likely organisms encountered. The antibiotic recommended is the parenteral form of cefazolin (Ancef), which has been shown to be very effective without the toxicity of other antibiotics. Orally administered capsules and tablets should not be used within the graft because they contain fillers that are not conducive to osteogenesis.

CONCLUSION

Dental implant and bone graft surgery has been shown to have a high incidence of infectious complications with a poor postoperative prognosis. Therefore, antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended when performing these procedures.

The literature-based prophylactic antibiotic protocol discussed in this article encompasses patient-specific factors as well as the invasiveness of the surgical procedure. The ideal antibiotics include the ß-lactam antibiotics, like those in the penicillin and cephalosporin families, with varying dosages and durations of treatment.

All third-party trademarks are property of their respective owners.

Available CE Course

References

-

Camps-Font O, Martin-Fatas P, Cle-Ovejero A, Figueiredo R, Gay-Escoda C, ValmasedaCastellon E. Postoperative infections after dental implant placement: variables associated with increased risk of failure. J Peridontol. 2018;89(10):1165-1173.

-

Grossmann Y, Levin L. Success and survival of single dental implants placed in sites of previously failed implants. J Periodontol. 2007;78(9):1670-4.

-

Machtei EE, Horwitz J, Mahler D, Grossmann Y, Levin L. Third attempt to place implants in sites where previous surgeries have failed. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(2):195-8.

-

Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Worthington HV. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: antibiotics at dental implant placement to prevent complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD004152.

-

Ata-Ali J, Ata-Ali F, Ata-Ali F. Do antibiotics decrease implant failure and post- operative infections? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43(1):68-74.

-

Chrcanovic BR, Albrektsson T, Wennerberg A. Prophylactic antibiotic regimen and dental implant failure: a meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(12):941-56.

-

Kim AS, Abdelhay N, Levin L, Walters JD, Gibson MP. Antibiotic prophylaxis for implant placement: a systematic review of effects on reduction of implant failure. BR Dent J. 2020;228(12):943-951.

-

Romandini M, De Tullio I, Congedi F, Kalemaj Z, D’Ambrosio M, Laforí A, Quaranta C, Buti J, Perfetti G. Antibiotic prophylaxis at dental implant placement: Which is the best protocol? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46(3):382-395.

-

Laskin DM, Dent CD, Morris HF, Ochi S, Olson JW. The influence of preoperative antibiotics on success of endosseous implants at 36 months. AnnPeriodontol. 2000;5(1):166-74.

-

Nolan R, Kemmoona M, Polyzois I, Claffey N. The influence of prophylactic antibiotic administration on post-operative morbidity in dental implant surgery. A prospective double blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014;25(2):252-9.

-

Peterson LJ. Antibiotic prophylaxis against wound infections in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(6):617-20.

-

Noroozi M. Self-reported penicillin allergy and dental implant therapy outcome, a clinical retrospective study. Diss. Univ British Columbia. 2015.1-128.

-

French D, Noroozi M, Shariati B, Larjava H. Clinical retrospective study of self-reported penicillin allergy on dental implant failures and infections. Quintessence Int. 2016;47(10):861-870.

-

Pichichero ME. Use of selected cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients: a paradigm shift. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57(3):S13-S18.

-

Wagenberg B, Froum SJ. A retrospective study of 1925 consecutively placed immediate implants from 1988 to 2004. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2006;21(1):71-80.

-

Bagheri Z, Barrese N, Rubinshtein G, Zahedi D, Malvin JN, Froum S. Dental implant failure rates in patients with self-reported allergy to penicillin. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2022;24(3)301-6.

-

Duewelhenke N, Krut O, Eysel P. Influence on mitochondria and cytotoxicity of different antibiotics administered in high concentrations on primary human osteoblasts and cell lines. Antimicrob Agents and Chemother. 2007;51(1):54-63.

-

Naal FD, Salzmann GM, Von Knoch F, Tuebel J, Diehl P, Gradinger R, Schauwecker J. The effects of clindamycin on human osteoblasts in vitro. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128(3):317-23.

-

Rashid MU, Weintraub A, Nord CE. Development of antimicrobial resistance in the normal anaerobic microbiota during one year after administration of clindamycin or ciprofloxacin. Anaerobe. 2015;31:72-7.

-

Khoury F, Javed F, Romanos GE. Sinus augmentation failure and postoperative infections associated with prophylactic clindamycin therapy: an observational case series. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2018;33(5):1136-1139.

-

Salomó-Coll O, Lozano-Carrascal L, Lazaro-Abdulkarim A, Hernandez-Alfaro F, Gargallo-Albiol J, Satorres-Nieto M. Do penicillin-allergic patients present a higher rate of implant failure?. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2018;33(6):1390-1395.

-

Basma HS, Misch CM. Extraction socket grafting and ridge augmentation failures associated with clindamycin antibiotic therapy: a retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2021;36(1):122-25.

-

Van Gasse AL, Ebo DG, Faber MA, Elst J, Hagendorens MM, Bridts CH, Mertens CM, De Clerck LS, Romano, A, Sabato V. Cross-reactivity in IgE-mediated allergy to cefuroxime: focus on the R1 side chain. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(3):1094-1096.

-

Sydnor A, Gwaltney JM, Cocchetto DM, Scheld WM. Comparative evaluation of cefuroxime axetil and cefaclor for treatment of acute bacterial maxillary sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115(12):1430-3.

-

Pichichero ME. Cephalosporins can be prescribed safely for penicillin-allergic patients. J Fam Pract. 2006.55(2):106-12.

-

Pichichero ME. A review of evidence supporting the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for prescribing cephalosporin antibiotics for penicillin-allergic patients. Pediatrics. 2005.115(4):1048-57.

-

Gallagher DM, Epker BN. Infection following intraoral surgical correction of dentofacial deformities: a review of 140 consecutive cases. J Oral Surg. 1980;38(2):117-20.

-

Urist MR, Silverman BF, Buring K, Dubuc FL, Rosenberg JM. The bone induction principle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1967;53:243-83.

-

Ketonis C, Barr S, Adams CS, Hickok NJ, Parvizi J. Bacterial colonization of bone allografts: establishment and effects of antibiotics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(8):2113-21.

-

Beardmore AA, Brooks DE, Wenke JC, Thomas DB. Effectiveness of local antibiotic delivery with an osteoinductive and osteoconductive bone-graft substitute. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(1):107-12.

-

Mabry TW, Yukna RA, Sepe WW. Freeze-dried bone allografts combined with tetracycline in the treatment of juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1985;56(2):74-81.